May 16th, 1229

Dandolo Docks, Porto di Venezia

Midmorning

”…and 89

grossi for the Doge,” the harbormaster said, finishing his tally; Gnupa frowned at him. Venetian officials were usually honest, in that they stuck to the traditional schedule of grease-money and didn’t try to double-dip, that was why Gnupa liked to do business there, but this man was new and might be trying to get one over on the foreigner.

“There’s no tariff on cotton goods,” he tried, just to see if the man might fold if his bluff was challenged. Instead he brought a parchment out of his satchel, and Gnupa’s heart fell to see the gold-and-red seals with the Lion of St Mark; if it was a bluff, it was a very elaborate one.

“There is now,” the harbormaster said, apologetically, and that made Gnupa believe him; if he was pocketing the money himself he would have smirked. “To pay for the Doge’s ships to go on the Crusade.”

“The Crusade, of course,” he said, rolling his eyes; behind him a low murmur ran through the Gangrels, waiting for the word to unload the goods. Of course it was the Crusade; damn the Crusade! Eighty-nine

grossi would not wipe out his profit on this run, he could raise his prices and take a little longer to sell and still come out ahead, but - it was the

arbitrariness of it that made his blood boil. Sigifredo was a trader, same as Gnupa, just with some more ships and warehouses; what gave him the right to suddenly charge extra for bringing goods into his city, just because he’d gotten it into his head to take up the Cross? Couldn’t he save his soul on his own

grosso?

Gnupa had no objection to the harbor fee, or the penny for the lighthouse, or even the ship money that paid for the Doge’s patrols up and down the Adriatic; those were all payments for work honestly done and pirates righteously hanged. Even the grease-money for the harbormaster was fair enough, you couldn’t well expect the man to live off his salary and his work was necessary. But the Crusade? What did Gnupa, or any trader, care whether the Mahometans held Jerusalem? He’d

been to Jerusalem, and perhaps his soul had profited but his accounts hadn’t; it was a flyspeck town that produced nothing except freshly-made saint’s relics for the most gullible pilgrims.

He felt the fury rise up from his belly, the deadly old

berserkergang that his father had fled Iceland to get away from, the

furore Normannorum that had uselessly killed so many who might instead have gotten rich from carrying goods in the long dragon-headed ships. For the first time in his life he agreed with it; this was no sensible tax-for-services-rendered, this was just plain thievery. But - who was there to fight? If he struck the harbormaster he’d be banned from the Porto, and quite rightly too; and he could not well fight the Doge, him in his one ship with thirty souls on board, counting the women and children…

Not today, at any rate.

August 23rd, 1251

Naqsh-e Rostam, Fars Province, Iran

An hour after dawn

The vanguard company was finally moving out, tall Gerald in the front unmistakable with his long red hair fluttering in the morning breeze. He was followed by a hundred men with long axes slung over their shoulders, supporting bindles with their worldly goods - except their long mail hauberks, which would follow in the wagons. Gnupa watched as they wended slowly down the valley, conserving energy for the long march ahead. It would be many months, and likely some skirmishing for a Persian lord with some gold and enemies to spare, before they were in Rome again.

And once in Rome… Gnupa looked down, yet again, at the sword on his belt, and put his right hand on the jeweled hilt to make sure it was still there. It would be Joyeuse, he decided. The Pope had been born a Bavarian peasant, neither Kurtana nor Bæsingr-Hneiti would mean anything to him - not in his heart of hearts where men kept the stories they heard as children. It was a fine sword, in any case, and he genuinely had found it in a magnificent tomb clearly built for a powerful king of ancient times; if it wasn’t the real Joyeuse - well, it would need a name, and the great Charles was welcome to raise an objection if he cared. Gnupa felt certain the Pope would not; the Pope was still a peasant at heart, uncertain of his welcome and his manners as he moved among kings and bishops; he would

want it to be Joyeuse, so he could display his connection to the Catholic emperors of old. Gnupa was a famous scholar, he had written no less than three books, he had famously converted the Sharif of Suriya. Stephanus would take his word for the identification, just so long as the agents he no doubt had planted among the Gangrels convinced him the sword hadn’t been bought in a market stall in Tehran. And it hadn’t been, so there should be no difficulty.

The vanguard had cleared the valley, and the shouted orders were going up for Torolf’s men to follow, another hundred tall splendidly-bearded men with long Lochaber axes and a bear’s-head banner and immense, insatiable appetites… the

cost of them! Gnupa’s merchant’s heart shrank just thinking about the bread they would eat, which he would have to pay for, on the way to Rome; but he could not do without them, not for the journey itself - a longer march than those amateurs in the Anabasis - nor for the war that would follow. Almost, almost, he could sympathize with the Doge’s tariff; fighting men were expensive beyond belief, they sucked silver out of the earth and drained it dry of grain, and for what? To kill people and burn fine things that someone had made by the sweat of their brow. Yet what could he do? He had set his heart against the disaster of the arbitrary tariffs; he would break that injustice, or it would break him - and if that meant spending silver as were it water, for fighting men and for the journey to find the Pope’s bribe, then he would spend it.

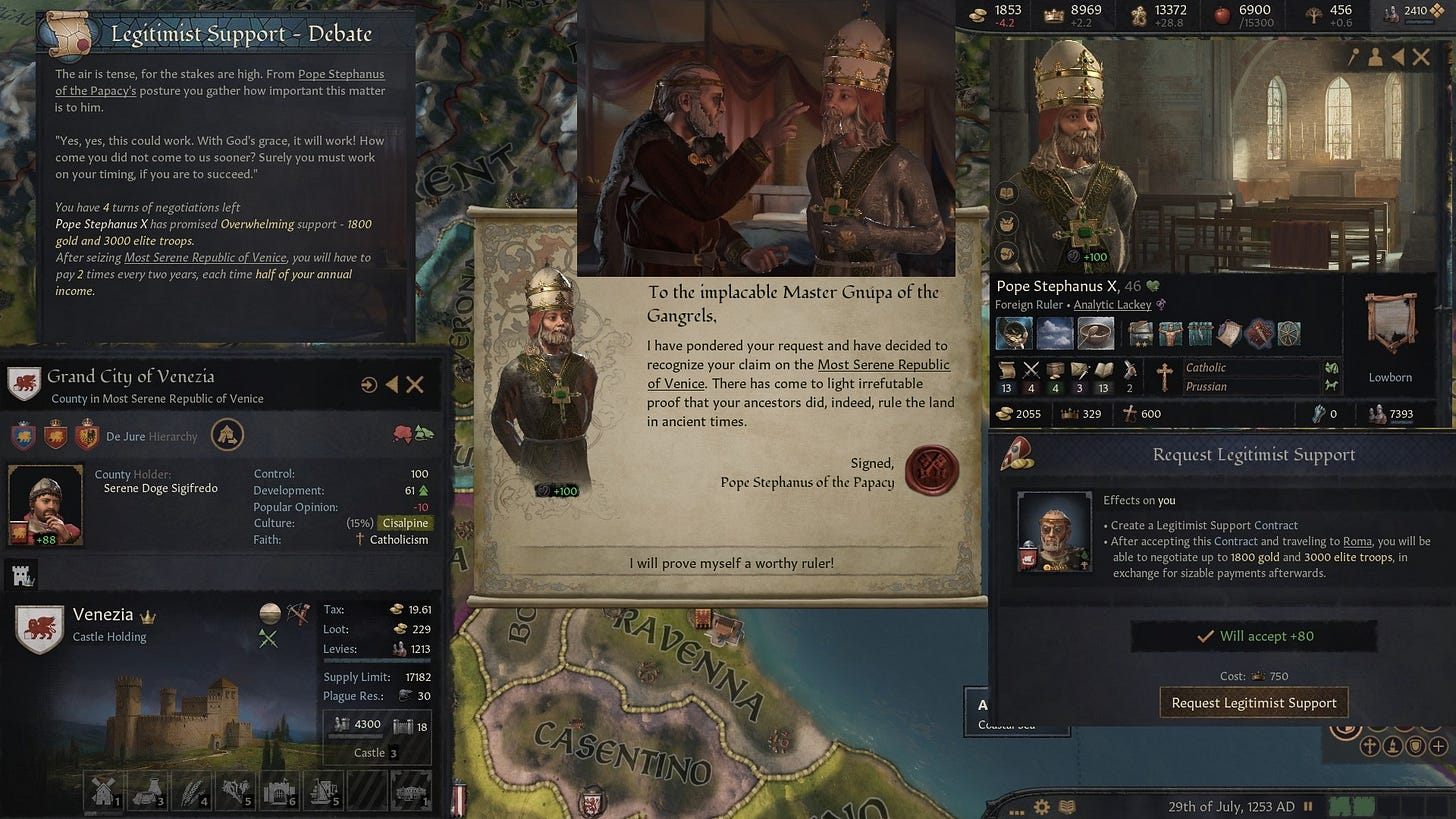

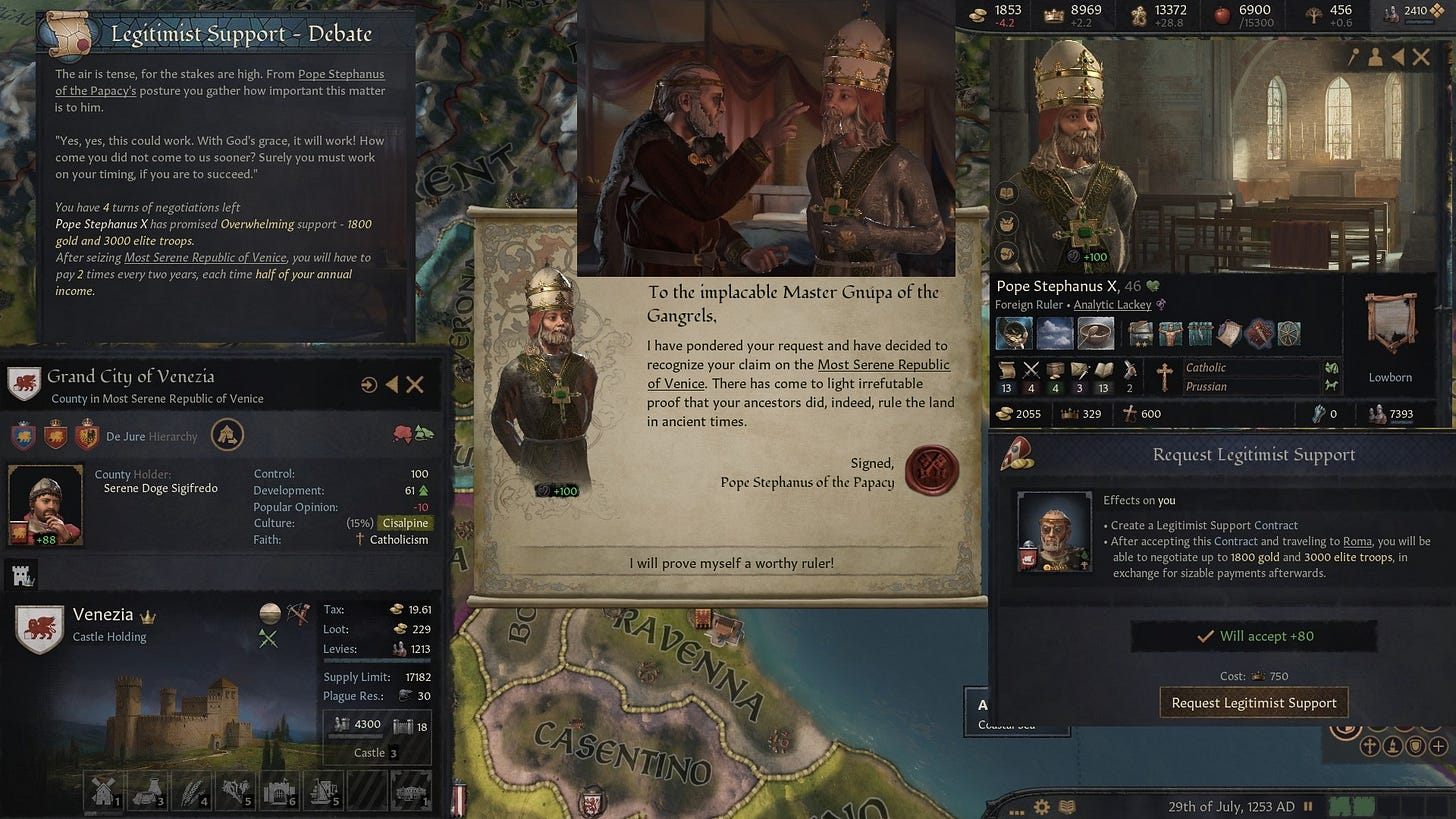

With the bribe of a max-quality artifact from the Far East, the Pope is

just barely willing to grant a claim on Venice to the landless wanderer from the far North.

July 1st, 1259

Dandolo Docks, Porto di Venezia

Midmorning

Gnupa had ordered his ships to carry dragon’s heads, for the sake of his ancestors’ pride; what would Ingimund Gamle have given, he that came from Norway in the land-taking, to raid so rich a city as Venice? But he felt no trace of the

berserkergang now, as company after company of his men debarked, formed up, and marched on the

Palazzo Ducale; only the cold, icy fury of a winter’s night in Reykjavik. And in the end, had not winter cold killed more men than any number of hot-blooded Vikings? This was no raid, no quick grab for cattle and slaves. He was here to end injustice; and to do so, he would have to depose the Doge - and rule himself. How else could he ensure that the injustice did in fact end? To his credit, Sigifredo had stopped collecting the tariff when the Crusade ended, but - that was not good enough. What was to stop him from imposing it again, if the Pope called again for swords about the Cross? Or his successor, perhaps for an even sillier cause? No; there was only one solution. If the sword was to decide who paid whom… then let the sword be the righteous Joyeuse, and let it be wielded by a man who understood the justice of free trade.

“No tariff on armed men,” Gnupa said bitterly to the harbormaster’s corpse, and followed Johann’s company towards the

Palazzo.