Hannover ~ a History

- Thread starter unmerged(62170)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hey sorry guys, by 'very soonly' I meant a few hours, not a few days! Election season has soaken up my time, but first update is mostly done, should be up later today.

There's an election campaign going on in the UK, the House of Commons is renewed on May 6th iirc

I

To Hannover, Go!

To Hannover, Go!

King Ernst August I

On 20 June 1837, the hundred and twenty-three year personal union of Great Britain and Hannover ended with the final breath of King William IV. While in Westminster young Princess Victoria of Kent would come to reign over an empire’s zenith, across the North Sea, a very different monarch would arrive. Ernst August, William’s younger brother, was deemed the new King of Hannover due to Salic law, barring women from the throne. A grizzled reactionary, Ernst August was known for his grim demeanour, autocratic views and hideous facial scars. As Duke of Cumberland he had been an omnipresent force in the House of Lords, fighting against electoral reform and Catholic emancipation, while rumours that he had a habit of ‘disposing’ of servants who displeased him only added to his harsh image. He was so disliked in Britain that on Victoria’s coronation a popular commemorative coin was minted showing the Duke on horseback above the phrase “to Hannover, go!”. When Ernst August arrived in his new kingdom however, he was given a rapturous reception. Hannover had only received one royal visit in the previous eighty years, and the prospect of a resident monarch for the first time in over a century roused the public. He paraded on horseback under a triumphal arch, specially built for the occasion.

The King was to quickly make his mark on Hannover. In 1833, William IV, an ardent Whig, had decided to give his second kingdom a liberal constitution, in line with the British Reform Act of the previous year. Baron George Frederick von Falke, a conservative noble and lawyer was aware of Ernst August’s political views and advised him that the constitution was illegitimate, because he as heir apparent had not been consulted. The King agreed and on 1 November annulled the constitution, declaring that Hannoverian government would reflect his personal values. This turn of events greatly upset liberals, and in particular Freidrich Dahlmann, the professor and politician who had written the 1833 Constitution. It was Dahlmann, who attempting to rally opposition to the King, gained the support of six fellow professors at the University of Gottingen, and issued a document detailing their criticisms. Within a matter of weeks all seven had been dismissed. However they were to become heroes of German liberalism, as Gottingen students, led by the radical Corps Hannovera fraternity published their declaration thousands of times over.

Kingdom of Hannover, 1836

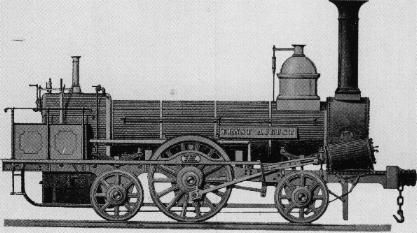

Despite his opposition to democracy, Ernst August should not be viewed as a stubborn anti-modernist. While he was unwilling to share political power, the King was extremely interested in improving Hannover in economic and social affairs. He had arrived in Hannover for the first time after sixty years of life in Britain and found it a small, backward place. Almost 80% of the population still worked on the land or the sea, while Hannover’s eponymous capital was dwarfed by the new industrial towns of England. The entire kingdom had a population of just over 1,750,000. Industry was limited to several small breweries and efforts to introduce the railway in the 1820s had been sunk by merchants invested in the dominant river trade. Ernst August took a visit south to the Duchy of Brunswick in 1840 and saw the tiny nation’s train system firsthand. It left an impression on the king and within a year he had established the Royal Hannoverian State Railway. The country’s first locomotive, aptly named the ‘Ernst August’, left Hannover City for Stade on 14 October 1841. This was followed with the first private railway, run by George Egestorff’s EGM-Hannover Company in January 1844. The King also helped improve his capital, investing in a modern sewage system and opening the grand Hannover State Opera in 1845. Despite his anti-Catholic views (he helped form the Orange Order in Britain), one of the King’s most progressive acts would be to emancipate his Jewish subjects, removing restrictions on synagogues, travel and government employment in September 1842, at least officially.

These policies would prove only partly successful however. Although the majority of the population accepted and benefited from the King’s reforms, with direct rule also leading to lower taxes, a small radical element still remembered the Gottingen Seven and was determined to return the 1833 Constitution. In June 1844, the liberals of the German states were emboldened by news from Greece. Popular unrest against the Bavarian-born King Otto had seen a new constitution drawn up. Soon copies of the documents and pamphlets on the events spread throughout middle-class and intellectual circles. In Stade, government spies uncovered an illegal printing operation intent on doing just that in Hannover. Although swiftly shut down, the imprisonment of a dozen activists only enflamed radical sentiment. As well as a wave of unrest building across Germany and the continent, along the North Sea coast, devastating storm tides destroyed harbours and fisheries in March 1845, ruining livelihoods, and contaminating water supplies leading to a fever epidemic. In the towns, despite a concerted effort to neutralise political agitators, the police struggled against organised crime. By 1846, corruption both criminal and official was rampant throughout Hannover. General public discord combined with an impending international political crisis was to prove a dangerous combination.

The 'Ernst August'

On 30 July the streets of Hannover City were a scene of chaos as working and middle class protestors clashed with the King’s own Corps de Garde, calling for a return of the Constitution and the removal of several key, and supposedly corrupt, officials from the city government. The clashes ran for hours, with hundreds of wounded and dozens dead but the result was never in doubt. Although an isolated incident and 1848, not 1846 is often considered the year of revolution in this period it should be noted that as well as Hannover, similar uprisings were taking place in Ireland, Galicia, Saxony, Westphalia and Baden. However the heads of Europe took little notice of the rash of unrest. Talk was not of revolution but of war, as British ships bombarded Toulon in August. The previous year’s stand-off over French incursions into Morocco had ballooned into full-blown conflict. Meanwhile in Germany, nationalist fervour reached fever pitch over the Schleswig-Holstein Question.

The whole complex affair was ultimately down to who held sovereignty over the predominately German duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, their ancient rulers the Danish kings or their ethnic brothers within the German Confederation. Such a problem was exacerbated by rising nationalism on both sides of the border. In May 1847, following protests in Copenhagen, the ageing King Christian VIII accepted liberal reforms to the constitution. This included binding his Duchy of Schleswig closer to Denmark. The move gravely angered his German subjects there and in Holstein. Soon, the issue was raised across Germany and militias on both sides began to form. German nationalists demanded action be taken and soon Berlin answered. Although only vaguely interested in the nationalist cause, Freidrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia saw the crisis as an opportunity to show his dominance over Austria and lead the pan-German cause. Within a matter of weeks Prussian troops were advancing towards Holstein. However things did not go as planned. While Austria promised troops, the other German states including Hannover made no such moves. Ernst August feared the growing undercurrent of radicalism would only be worsened by war, while absent troops would give would-be revolutionaries the advantage. On their own, Prussian troops found their Danish opponents dug-in and well-equipped. It would take several months and the arrival of Austrian reinforcements before Kiel alone would fall. Meanwhile the Hannoverian king would be proven right, as 1848 would see Europe enter a year of great upheaval and revolution.

Last edited:

How could they bomb Toulouse?

Toulon you mean?

Maybe Hannover should attack someone, with a foe from the outside, inner problems might be forgotten.

Toulon you mean?

Maybe Hannover should attack someone, with a foe from the outside, inner problems might be forgotten.

Maybe Hannover should attack someone, with a foe from the outside, inner problems might be forgotten.

Or it might spawn a full-blown revolution. Great work, Hannover's an interesting choice.

Or it might spawn a full-blown revolution. Great work, Hannover's an interesting choice.

The full-blown revolution shall be dealt after the war.

They never revolt in time.

Ah, yes Toulon my bad, my ignorance always makes me assume its the French name for Toulouse. Let the idiocy of that sentence sink in.

The early years of this AAR will be relatively calm but lets just say by the 1860s thing will start to heat up. Hannover is just biding its time.

Next update today or tomorrow.

The early years of this AAR will be relatively calm but lets just say by the 1860s thing will start to heat up. Hannover is just biding its time.

Next update today or tomorrow.

Dr G returns! I was worried all that time along side Jape has led you astray, he's not to be trusted that Jape. A notorious abandoner.

So you abandon Britain for Hanover, that could be interesting and I look forward to seeing if you manage to avoid being eaten by your vast array of larger neighbours.

So you abandon Britain for Hanover, that could be interesting and I look forward to seeing if you manage to avoid being eaten by your vast array of larger neighbours.

Sorry for the delay, been running around for the election, exams and changed computers so all busy, busy. Next update 90% done so soon.

Speaking of Jape, our long suggested mod/ATL based on EdT's A Greater Britain might be arriving in the near future. Eventually.

Speaking of Jape, our long suggested mod/ATL based on EdT's A Greater Britain might be arriving in the near future. Eventually.

Seize Texas/California from Mexico  a 100k Cavalry expedition should do the job.

a 100k Cavalry expedition should do the job.

Last edited: