Here Dwells God - A Jewish Poland AAR, Part Four

- Thread starter Tommy4ever

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 35 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Interlude - Football in Postwar Poland 1959-1963 – Nothing Without God 1963-1965 – Home Rule? 1968-1969 - Echoes of an Old Tune 1969-1972 It's Always Been Burning, Since the World's Been Turning 1972-1973 The Second Baltic War 1973 Debellatio 1973-1975 The Black Month of MayI think the fact that the Russians have started using nukes against civilian targets may factor into this as well. If the Allies restrict their use of nukes to things that they can plausibly argue are military targets, they can claim to still possess moral superiority. Of course, who knows what the AI will actually do?The question of a taboo over using the nukes for the democratic powers is another question. On the one hand, Russia's use of the weapons can be painted as a uniquely barbaric act, while also normalising it. Should the Americans ready their bomb with the war still in the balance, they may need to way up the cons of a reputational black mark against the pros of the military benefit (not to mention the geopolitical flex involved in showing the world that you too are a nuclear power). Considering the way in which Russia is viewed as the ultimate evil (in America, with its Muslim population, especially), its easy to see how an moral exception could be made.

I'm now very interested in Russia's manpower situation.

The overall narrative definitely seems to be careening towards an internal and external collapse of the Radical state if victory is not achieved very soon (which, considering the number of fronts, doesn't seem likely). I imagine that, if you reach the point where your armies can no longer reinforce, and there's an accelerating collapse as they're too undermanned to provide resistance or simply outright get wiped out, it would feed quite well into the kind of end to all this that mirrors OTL's WWI.

The Summer Offensive seemed like it might decide the war in the Germans' favour but, without getting that all-important breakthrough, the men and materiel expended actually hastened the end of the war, as the Allied counter-offensive then fell upon a completely exhausted and defensively exposed Imperial Army.

Of course, this assumes the Radicals' Deal with the Devil doesn't bail the bastards out yet again.

The overall narrative definitely seems to be careening towards an internal and external collapse of the Radical state if victory is not achieved very soon (which, considering the number of fronts, doesn't seem likely). I imagine that, if you reach the point where your armies can no longer reinforce, and there's an accelerating collapse as they're too undermanned to provide resistance or simply outright get wiped out, it would feed quite well into the kind of end to all this that mirrors OTL's WWI.

The Summer Offensive seemed like it might decide the war in the Germans' favour but, without getting that all-important breakthrough, the men and materiel expended actually hastened the end of the war, as the Allied counter-offensive then fell upon a completely exhausted and defensively exposed Imperial Army.

Of course, this assumes the Radicals' Deal with the Devil doesn't bail the bastards out yet again.

The satisfaction of seeing Russia plough itself into the ground is massively offset, I have to say, by the fact that it seems intent on taking everyone down with it…

- 1

It surprises me that the IA still does not have A-bombs even in the 50s. Anyway, yours is one of the few AARs that both original, engaging and coherent (all four). Congratulations!

I do wonder what the end game would be for Russia. Even if they manage to conquer Eurasia and Africa, I have no idea how they’d reach the Americas. I can’t imagine the Polish have a Navy on the level of the US.

Jesus, another nuke detonation. Russia better be ready to face off against a now angered Chinese nation, especially now that they WILL retaliate with extreme prejudice for every dead civilian in those nuked cities. I certainly hope Golikov gets what is coming to him eventually, that madman needs to pay for his crimes. Justice for the millions he signed an atomic death.

I also am curious about Russia's manpower situation. Also is there American Strategic bombing? If I were the Americans with inroads into Finland and also reaching the gates of Odessa I would be trying as hard as possible to hit Kiev/ukraine as well as Infrastructure by the front

When Russia loses, its going to face a terrible peace treaty. It's not going to have any mercy from countries who had their civilian populations nuked.

Golikov is going to burn the world down just so that he can make himself king of the ashes.

1950-1951 – The End of the Beginning

1950-1951 – The End of the Beginning

In Asia, the Russian counterattack that began in the final months of 1950, accompanied by the meting out of fiery destruction on urban China with the Republic’s new missile arsenal, was a great success. Although fast progress in a territory so inhospitable and endless in size was not realistic, from the end of 1950 the Chinese were putting into a long retreat away from the industrial centres of Western Siberia, back towards the pre-war frontier. By the summer of 1951 the Russians had pushed back into the Mongol and Uighur lands. Importantly, a large number of China’s most experienced divisions, most skilled in Arctic combat, were cut off from the front north of Lake Baikal. Living off the land in these territories was already impossible in the summer, but when the weather turned later in the year the Chinese caught in the tundra quickly began to die in scores, with the Russians delaying their acceptance of their surrender for several weeks to allow the elements to reduce their enemies numbers.

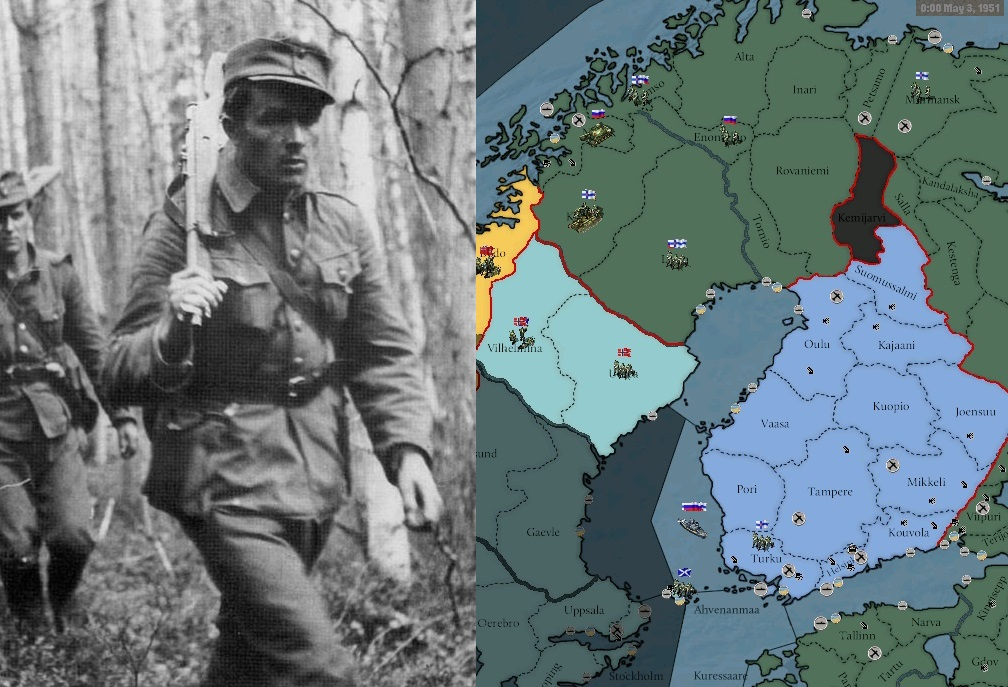

Back in Europe, while the Northern Front had gained a great deal of attention from Allied and Eurasian strategists alike during the first year of the war when the Allies had threatened to push all the way to Muscovy, since the Russians had regained the upper hand in the second half of 1949 it had retreated from prominence. The battles tended to be smaller scale, less frequent and less bloody than other theatres of battle while the frontline remained relatively steady in the Lapland area, although the Russians made steady progress over the course of the next two years – pushing back into Scandinavia proper in 1951.

On the home front, the winter of 1950 to 1951 was extremely harsh in Russia. Civilian living conditions were seemingly in free fall with rations of food and fuel drastically reduced while the state made ever greater demands of the workforce for higher production in the name of total war. Worse, from the end of 1950 the Judaeo-Russian heartland of the empire witnessed the arrival of violence on its own doorstep for the first time since the invaders of the Internationale had been swept out of Russia during the previous war. Allied victories around the southern shores of the Black Sea had provided bases for bombing raids into Ukraine – reaching as far as Kiev itself – while a growing aerial advantage for the Allies limited Russia’s ability to keep the skies over its heartlands safe from bombing.

In Western Europe, after a year of static trench warfare across a front stretching from the North to the Ligurian Seas that had seen neither side land a decisive blow or make anything more that marginal territorial gains, the Russians in particular limited by the diversion of the Republic’s nuclear arsenal to Asia, the Eurasian League won a great victory. On July 1st 1951 the Dutch capital of Amsterdam finally fell after more than a year under siege and the entire Dutch army surrendered to the League. Just a week later thirty thousand Americans were captured following a failed landing behind Russian lines at Wilhelemshaven. These victories were believed to be of incredible significance to the outcome of the war – removing another European belligerent from the fight, freeing up large numbers of Russian troops that had been involved in the siege for attacks elsewhere on the front and striking a dispiriting psychological blow to the Allies. Golikov confidently celebrated the victory across the Russian airwaves, swearing that the enemy was near defeat, and that with one last push the Russian flag would be flying over Paris by Hanukah.

Kiev’s desperation for success in the West was growing as the situation its southern flank deteriorated. Following a number of gruesome battles in 1950, the Allies had captured most of the South Caucuses, however the Russians still held a strong line across the highest peaks of the mountain range. Troublingly, the Allies were able to overwhelm these positions too in early 1951, and with far fewer causalities than they had suffered the previous year, finally pushing beyond the difficult mountain terrain that the Russian defence had depended upon as they reached towards the open country of the Steppe. Despite pouring greater resources into the Front, the Russians now had few natural defensive lines to hold the Allies in check. Worse, as their enemies progressed into Tatar-populated provinces they found a friendly local population that was eager to aid them in every way possible and found new possibilities for cooperation with nationalist partisans behind enemy lines.

The resurgence in minority nationalist militancy within Russia would play its part in one of the most spectacular, and consequential, dramas of the war. Since first deploying them in 1949, Russia’s use of nuclear weapons had been successful in greatly altering the balance of power in the war. Having kept its secrets tightly under wraps, it enjoyed a monopoly on these weapons, despite the best efforts of Allied researchers to develop a bomb of their own. In the summer of 1951 American intelligence agencies made a crucial discovery – identifying the location of Russia’s only operational nuclear production facility, high in the Ural Mountains. Unable to reach this location themselves, the Americans turned to friendly partisans within Russia.

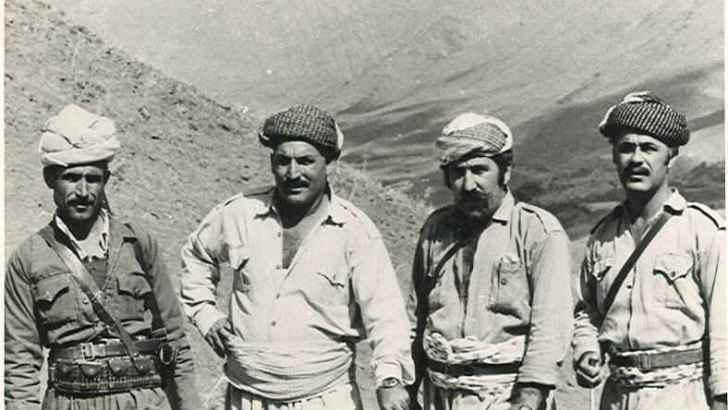

The Brotherhood of the Wolf, the famous Turanist rebel group, had been almost completely destroyed under the jackboot of Radical Party repression over the preceding decades. However, the wavering of Russian state authority under the weight of the present war had given it an opportunity for explosive resurgence. Working closely with American intelligence services, many of whom where of Tatar extraction themselves, the Brotherhood’s finest hour would come in September 1951. Gathering its hundreds of its best fighters to a single location, the Brotherhood launched an audacious raid on the secret nuclear facility – damaging it so badly with mortal fire and bombs to put it out of operation for months.

Just as importantly, the Turanists were able to capture three nuclear scientists alive, and within hours of their arrival, disappeared back into the mountains. In their dramatic adventure to smuggling these men out of Russia, two of the three scientists were killed as Russian security forces tracked down the bands of Brotherhood fighters one by one. However, one man, a Latvian named Valarian Broka, was brought to the shores of the Caspian, from where American agents were able to arrange a flight over the sea to Baku and, from there, the safety of North America. Broka would go on to supercharge the American nuclear programme, putting them on track to produce a bomb of their own. In a single raid, the Brotherhood of the Wolf had done more to damage the Russian state than in their decades of rebellions, insurgency, assassination and propaganda.

The Wolves’ remarkable raid came at the tail end of a summer during which the United States had seized the initiative in Europe to turn the balance of the war firmly against Russia. In truth, the United States, reluctant to fully abandon the liberties of normal life, had been more skittish than any other power in truly embracing total war. With a much lower rate of conscription than all other major belligerents both in the wars of the 1940s, much of its war making potential remained untapped. Only the nuclear bombings in Germany in 1949 had convinced New Cordoba of the need to embrace total warfare and rally every available man to the fight. The United States already had millions on men in the field in 1949, but within two years these numbers would almost double as America approached the levels of mobolisation seen across Europe. These resources would provide the Americans with the strategic freedom to change the shape of the war.

In early July 1951 the Americans embarked on a series of large-scale landings around the sun bleached beaches of Greece. Caught off guard, Crusader Anatolia quickly folded as its coastal defences proved completely inadequate. The surrender of the Greeks allowed fast moving American units to drive deep into the barely protected Balkans – reaching the Danube before the end of the month. Worse was to come, as the Russians moved troops out of Thrace to counter the Americans, Allied troops stationed in Asia Minor were able to force the Bosporus and capture the Queen of Cities itself, Constantinople.

With the Allies opening up a new front in the Balkans, and knocking out a key player in the Eurasian League out the war, another American naval invasion in Europe upturned the balance of power on the Western Front. With the Russians still beaming from their victory over the Dutch in Amsterdam, in August around a quarter of a million American troops flooded into the flat lands of Holland, capturing tens of thousands of Eurasian troops and sending the rest of their force in the region into flight back towards Germany. This naval invasion was accompanied by a surge in American commitment across the Western Front in the summer of 1951 to steady the line and prepare to roll back the Russian threat.

At home, unwelcome news from the front contributed to the growing dissident mood across the Republic. In late August shipyard workers in Gdansk began a major wildcat strike, protesting against a government push to extend their working day to nearly 14 hours. To the consternation of the regime, the strikers adopted an unthinkably political tone – chanting for peace and freedom. The Radicals responded in typical fashion, deploying armed police to break up the strike and punish the ring leaders. However, from here, events escalated with a violent industrial dispute transforming into an outright insurrection, with armed groups of workers from across the ethnically diverse city joining together in revolt against the regime – an act in itself something of a repudiation of Radicalism’s belief in the primacy of race and ethnicity above all else. For a period of three weeks through September 1951 the Free City of Danzig held sway over the important port city, with Allied aircraft flying in weapons and supplies to help the locals keep up the fight before order was restored. Increasingly, the enemy within was presenting itself as almost as great a threat as Russia’s myriad external foes.

Last edited:

- 7

- 1

Things are taking an unwelcome turn for Russia.

The Brotherhood of the Wolves' raid isn't actually entirely divorced from the game. Through the war I have been deliberately allowing my dissent to rise (as a proxy for war exhaustion and to make up for the fact that the game mechanic of manpower is pretty broken by this stage of the game), we've now reached the point were rebels are not uncommon. One group rose up in the province I had my nuclear reactor in - halting all nuke production for basically the whole of 1951.

The Chinese can thank those Tatar partisans for preventing Russia dropping any more nukes on their cities for now, although their hopes of conquest across Siberia and Central Asia have been dealt a heavy blow here.

Indeed, and now with Russian nuclear scientists in Allied hands, we are likely to see the Allies have nuclear capability in the near future - when these questions will finally have to be decided.

Here is where the game and story divide somewhat. In game, I have basically unlimited manpower at this point because of the way you can accumulate it in DH. I started this was with about 17k manpower, and we are down to 9k now - so it is dropping, but that's still a pretty ridiculous number to have in reserve, after a decade of total war. In our story, we are at the stage where we would be scraping the barrel for men - causing labour shortages everywhere.

This is why I decided to allow my dissent to gradually accumulate over the course of the war - it models both Russian society internally breaking down, and gives a ticking clock element to make up for the in-game manpower issues. Dissent gives you revolts all over your provinces, makes your economy less efficient - but also impacts upon the effectiveness of your soldiers on the ground.

To rescue this, the Russians really need to get their reactor back up and running ASAP, but its starting to look like the tide is going out too far for the situation to be salvageable.

Certainly, and not just in terms of the 5 nuclear bombings. Half of Europe and much of Asia will be in ruins from conventional weapons as well, not to mention the millions killed fighting.

Yes, although if they had developed them this war might have been a bit less interesting - the Allies would probably have been able to steamroll me within a year or two if they have been able to use them.

And I am glad you are still enjoying the story 1,000 years in!

In terms of fleets, I actually spent the brief interwar period investing heavily in building some modern naval units. However I was so badly outnumbered at sea I only ever really used them for some hit and run raids when I noticed small Allied fleets about. I didn't include them in updates because the war at sea was so boring, and my ships didn't even manage a single exciting naval battle - they ended up getting destroyed by naval bombers.

So a long story short, if Russia turned this around and conquered Eurasia, then we would have the tech (and obviously the industrial capacity) to spam out modern fleets - we would just have a time lag of a few years while they were built up.

We will have to have a poll to see who is the most hated character - Makarov or Golikov!

These nuclear attacks in China are different to those in Germany in the way that they were explicitly aimed at civilian rather than military targets. We shall see if the Chinese can recover from the damage enough to mete out some vengeance.

We're only just getting to the stage where Allied bombers can really hit the Russian industrial heartlands consistently. I still have a very big airforce, even if it has fallen further and further behind over the course of the war, by this stage I had long since abandoned using offensive airpower except in a very target way and was concentrating on defending my own troops and cities - so a long distance flight across Russia was pretty dangerous for Allied bombers even at this stage. So they needed bases close to my cities to be effective, which they now have.

If Russia loses it can be certain that its great empire is going to be completely Balkanised and heavy exactions put upon it. The big question will be whether it can maintain its real independence into the postwar period in the event of defeat.

Not if the Brotherhood of the Wolf has its way!

Nice to see the internal partisans, and a well liked returning faction in the AAR, actually playing a decisive military role.

The Brotherhood of the Wolves' raid isn't actually entirely divorced from the game. Through the war I have been deliberately allowing my dissent to rise (as a proxy for war exhaustion and to make up for the fact that the game mechanic of manpower is pretty broken by this stage of the game), we've now reached the point were rebels are not uncommon. One group rose up in the province I had my nuclear reactor in - halting all nuke production for basically the whole of 1951.

Concerning developments all over, and especially in the East.

The Chinese can thank those Tatar partisans for preventing Russia dropping any more nukes on their cities for now, although their hopes of conquest across Siberia and Central Asia have been dealt a heavy blow here.

I think the fact that the Russians have started using nukes against civilian targets may factor into this as well. If the Allies restrict their use of nukes to things that they can plausibly argue are military targets, they can claim to still possess moral superiority. Of course, who knows what the AI will actually do?

Indeed, and now with Russian nuclear scientists in Allied hands, we are likely to see the Allies have nuclear capability in the near future - when these questions will finally have to be decided.

I'm now very interested in Russia's manpower situation.

The overall narrative definitely seems to be careening towards an internal and external collapse of the Radical state if victory is not achieved very soon (which, considering the number of fronts, doesn't seem likely). I imagine that, if you reach the point where your armies can no longer reinforce, and there's an accelerating collapse as they're too undermanned to provide resistance or simply outright get wiped out, it would feed quite well into the kind of end to all this that mirrors OTL's WWI.

The Summer Offensive seemed like it might decide the war in the Germans' favour but, without getting that all-important breakthrough, the men and materiel expended actually hastened the end of the war, as the Allied counter-offensive then fell upon a completely exhausted and defensively exposed Imperial Army.

Of course, this assumes the Radicals' Deal with the Devil doesn't bail the bastards out yet again.

Here is where the game and story divide somewhat. In game, I have basically unlimited manpower at this point because of the way you can accumulate it in DH. I started this was with about 17k manpower, and we are down to 9k now - so it is dropping, but that's still a pretty ridiculous number to have in reserve, after a decade of total war. In our story, we are at the stage where we would be scraping the barrel for men - causing labour shortages everywhere.

This is why I decided to allow my dissent to gradually accumulate over the course of the war - it models both Russian society internally breaking down, and gives a ticking clock element to make up for the in-game manpower issues. Dissent gives you revolts all over your provinces, makes your economy less efficient - but also impacts upon the effectiveness of your soldiers on the ground.

To rescue this, the Russians really need to get their reactor back up and running ASAP, but its starting to look like the tide is going out too far for the situation to be salvageable.

The satisfaction of seeing Russia plough itself into the ground is massively offset, I have to say, by the fact that it seems intent on taking everyone down with it…

Certainly, and not just in terms of the 5 nuclear bombings. Half of Europe and much of Asia will be in ruins from conventional weapons as well, not to mention the millions killed fighting.

It surprises me that the IA still does not have A-bombs even in the 50s. Anyway, yours is one of the few AARs that both original, engaging and coherent (all four). Congratulations!

Yes, although if they had developed them this war might have been a bit less interesting - the Allies would probably have been able to steamroll me within a year or two if they have been able to use them.

And I am glad you are still enjoying the story 1,000 years in!

I do wonder what the end game would be for Russia. Even if they manage to conquer Eurasia and Africa, I have no idea how they’d reach the Americas. I can’t imagine the Polish have a Navy on the level of the US.

In terms of fleets, I actually spent the brief interwar period investing heavily in building some modern naval units. However I was so badly outnumbered at sea I only ever really used them for some hit and run raids when I noticed small Allied fleets about. I didn't include them in updates because the war at sea was so boring, and my ships didn't even manage a single exciting naval battle - they ended up getting destroyed by naval bombers.

So a long story short, if Russia turned this around and conquered Eurasia, then we would have the tech (and obviously the industrial capacity) to spam out modern fleets - we would just have a time lag of a few years while they were built up.

Jesus, another nuke detonation. Russia better be ready to face off against a now angered Chinese nation, especially now that they WILL retaliate with extreme prejudice for every dead civilian in those nuked cities. I certainly hope Golikov gets what is coming to him eventually, that madman needs to pay for his crimes. Justice for the millions he signed an atomic death.

We will have to have a poll to see who is the most hated character - Makarov or Golikov!

These nuclear attacks in China are different to those in Germany in the way that they were explicitly aimed at civilian rather than military targets. We shall see if the Chinese can recover from the damage enough to mete out some vengeance.

I also am curious about Russia's manpower situation. Also is there American Strategic bombing? If I were the Americans with inroads into Finland and also reaching the gates of Odessa I would be trying as hard as possible to hit Kiev/ukraine as well as Infrastructure by the front

We're only just getting to the stage where Allied bombers can really hit the Russian industrial heartlands consistently. I still have a very big airforce, even if it has fallen further and further behind over the course of the war, by this stage I had long since abandoned using offensive airpower except in a very target way and was concentrating on defending my own troops and cities - so a long distance flight across Russia was pretty dangerous for Allied bombers even at this stage. So they needed bases close to my cities to be effective, which they now have.

When Russia loses, its going to face a terrible peace treaty. It's not going to have any mercy from countries who had their civilian populations nuked.

If Russia loses it can be certain that its great empire is going to be completely Balkanised and heavy exactions put upon it. The big question will be whether it can maintain its real independence into the postwar period in the event of defeat.

Golikov is going to burn the world down just so that he can make himself king of the ashes.

Not if the Brotherhood of the Wolf has its way!

Nice to see the internal partisans, and a well liked returning faction in the AAR, actually playing a decisive military role.

- 4

The Brotherhood have earned their place in history as heroes in the eyes of humanity. That raid certainly was awesome, the stuff of legends, hell movies and video games certainly would use that. If the war ever ends I can see this raid being a highlight for this universe's Wolfenstein series.

- 1

The Tatars are back, baby!Just as importantly, the Turanists were able to capture three nuclear scientists alive, and within hours of their arrival, disappeared back into the mountains. In their dramatic adventure to smuggling these men out of Russia, two of the three scientists were killed as Russian security forces tracked down the bands of Brotherhood fighters one by one. However, one man, a Latvian named Valarian Broka, was brought to the shores of the Caspian, from where American agents were able to arrange a flight over the sea to Baku and, from there, the safety of North America. Broka would go on to supercharge the American nuclear programme, putting them on track to produce a bomb of their own. In a single raid, the Brotherhood of the Wolf had done more to damage the Russian state than in their decades of rebellions, insurgency, assassination and propaganda.

I admire your discipline of handicapping yourself on purpose with dissent when the enemy is gaining the upper hand, somebody else could've just beaten the hell out of the rest of Eurasia and call it an end. Great job on making this such a compelling story!

The Brotherhood of the Wolf, the famous Turanist rebel group, had been almost completely destroyed under the jackboot of Radical Party repression over the preceding decades. However, the wavering of Russian state authority under the weight of the present war had given it an opportunity for explosive resurgence. Working closely with American intelligence services, many of whom where of Tatar extraction themselves, the Brotherhood’s finest hour would come in September 1951. Gathering its hundreds of its best fighters to a single location, the Brotherhood launched an audacious raid on the secret nuclear facility – damaging it so badly with mortal fire and bombs to put it out of operation for months.

Just as importantly, the Turanists were able to capture three nuclear scientists alive, and within hours of their arrival, disappeared back into the mountains. In their dramatic adventure to smuggling these men out of Russia, two of the three scientists were killed as Russian security forces tracked down the bands of Brotherhood fighters one by one. However, one man, a Latvian named Valarian Broka, was brought to the shores of the Caspian, from where American agents were able to arrange a flight over the sea to Baku and, from there, the safety of North America. Broka would go on to supercharge the American nuclear programme, putting them on track to produce a bomb of their own. In a single raid, the Brotherhood of the Wolf had done more to damage the Russian state than in their decades of rebellions, insurgency, assassination and propaganda.

The Wolves’ remarkable raid came at the tail end of a summer during which the United States had seized the initiative in Europe to turn the balance of the war firmly against Russia. In truth, the United States, reluctant to fully abandon the liberties of normal life, had been more skittish than any other power in truly embracing total war. With a much lower rate of conscription than all other major belligerents both in the wars of the 1940s, much of its war making potential remained untapped. Only the nuclear bombings in Germany in 1949 had convinced New Cordoba of the need to embrace total warfare and rally every available man to the fight. The United States already had millions on men in the field in 1949, but within two years these numbers would almost double as America approached the levels of mobolisation seen across Europe. These resources would provide the Americans with the strategic freedom to change the shape of the war.

- 3

Things seem bad for Russia (but brighter for the world). Even though the eastern front has been stabilized, the western front is probably on the verge of collapse, unless nuclear production can be restarted quickly and a few bombs used to break up advancing armies. In this regard, the Brotherhood of the Wolf might have had the biggest impact of any partisan force known in this universe or ours. And the southern front, of course, is barely a front at all. How many Russian divisions remain between the Caucasus and the industrial heartland?

The Brotherhood returns! And what a return it was! Now, the rest of the world might have a chance. If America can develop the bomb, that would turn the tide of the war immensely. Do we know how long it takes for America to research the technology?

I'm concerned about the state of the European allies. There's not many countries standing in Russia's way...

I'm concerned about the state of the European allies. There's not many countries standing in Russia's way...

BRING THE GOOD OLD BUGLE BOYS WE'LL SING ANOTHER SONG

SING IT WITH A SPIRIT THAT WILL START THE WORLD ALONG

SING IT AS WE USED TO SING 500,000 STRONG

WHILE WE WERE MARCHING THROUGH GEORGIA

- 7

The capture of Amsterdam does seem to provide a sort of Operation Michael moment. One last hurrah, followed by brutal reverses and internal collapse.

Here's to hoping the good fortune continues, Golikov is strung up, and Radicalism rooted out with surgical precision.

Here's to hoping the good fortune continues, Golikov is strung up, and Radicalism rooted out with surgical precision.

- 1

Threadmarks

View all 35 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode