Excerpt from the Introduction of History of the Byzantines Volume III (1059-1450)…

This is the third installment of the grand history of the Byzantines. The first volume of the series concerned early Byzantine history from Konstaninos I to Heraclius using the Muslim invasions as a natural cutoff point. The next volume chronicled the empires history during the dark ages from the Muslim invasions to Isaakios Komnenos abdicated in 1059. This volume starts with Konstaninos X taking control of the empire after Isaakios’s abdication in 1059 because this would provide the necessary background going into the reign of St. Konstaninos the Good. Now before starting this volume in earnest let’s look at how the empire got here…

The young Michael VII Dukas was crowned senior emperor in 1067. Shortly after his coronation Michael was given an ultimatum by Romanos Diogenes. Romanos demanded senior co-emperorship with Michael, and the removal of Michael’s brother, junior emperor Konstaninos from the capitol. Michael fearing war with the powerful and popular Romanos quickly conceded giving his seven year old brother the title Kome’s of Syracuse. Early in his reign his uncle, Ioannes Dukas, attempted to usurp the throne from his significant lands in Bulgaria, but Romanos defeated and executed him in 1073. Around the same time Mihajlo Vojislavljevic invaded the Serbian Themes of the empire, and in 1075 slew Michael VII at the battle of Belgrade.

Romanos IV Diogenes became the sole senior emperor after Michael’s death in 1075. After hearing of Michael’s death, Alexios Komnenos rose in revolt with significant support throughout Anatolia and Armenia, along with the help of Mihajlo who at this time had just stormed Belgrade. Romanos then sent a mercenary army under the command of Romanos Argyros to put down the rebellion in its heartland, but after a secret meeting with Alexios the mercenary captains switched sides handing their commander over to Alexios. With his son as a hostage, Alexios forced Theodoros Argyros, Doux of Athens, to desert Diogenes’s cause, and join the Kommeni camp.

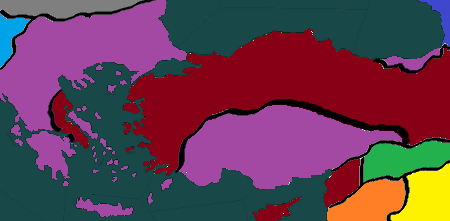

The Kommeni Rebellion after Theodoros’s defection Red stands for lands supporting the Kommeni and Purple are lands loyal to Diogenes. The two strongest forces at Romanos’s disposal at this time were his Thema, and the few Imperial Tagmas to survive Konstaninos’s purges. In the winter of 1082 he gathered his Tagma at Adrianople, while simultaneously sending his basterd brother Nikephoros to lead his Thema in Anatolia. Alexios meanwhile, after dispatching some troops to harry Nikephoros, slipped 12,500 of his men across the Bosporus in the spring and laid siege to Constantinople. As the Constantinople city fathers prepared to surrender the keys to the city, Romanos forced marched his 7,500 to the capitol and attacked Alexios in the early dawn. With Alexios’s host still largely asleep and in camp, it was more of a massacre than a battle though Alexios himself along with 5,000 men made it across the Marmara. After this debacle Alexios’s supporters handed him over to Romanos for a promise of amnesty. Alexios was blinded and imprisoned until Romanos’s death.

Thus after 10 years of sporadic civil war, the Empire was at peace, though large portions of Anatolia still were only nominally subjected. For the next five years Romanos fought the large bands of lawless mercenaries who after being discharged from military service, plagued the countryside as bandits. He also restored the fleet that was cut in size under Konstaninos. A large portion of this new fleet was sent to Syracuse; where under the guardianship of the future Konstaninos XI they launched numerous raids against the Arabs and Italians. These raids would culminate in the battle of Cape Corse where the Byzantines heavily defeated an Italian coalition, and after extracting significant tribute returned in triumph to Syracuse. Sicily would also be the sight of the greatest triumph of Romanos’s reign. In 1084 the young Konstaninos Dukas, son of the late Konstaninos X and brother of Michael VIII, rapidly campaigned across Sicily. Konstaninos was able to seize Palermo in May, Agrigento in June, and Trapani in August. In little over a summer, the young man conquered a prize that had eluded Emperors for centuries. This would greatly improve Konstantinos’s popularity and fame among the commoners and nobles alike; during his triumph in Constantinople he was awarded the title Strategos of Sicily. In the last two years of his life Romanos having defeated the bandits raised a large veteran army, and marched along Anatolia forcing obedience to among the largely independent princes there. But in July 1085 a minor border incident with the Seljuk Turks spiraled out of control, and lead to Romanos declaring war. A week and a half later he was poisoned by person’s unknown thereby leaving his uncrowned, five year old son Stephanos in Constantinople.

This is the third installment of the grand history of the Byzantines. The first volume of the series concerned early Byzantine history from Konstaninos I to Heraclius using the Muslim invasions as a natural cutoff point. The next volume chronicled the empires history during the dark ages from the Muslim invasions to Isaakios Komnenos abdicated in 1059. This volume starts with Konstaninos X taking control of the empire after Isaakios’s abdication in 1059 because this would provide the necessary background going into the reign of St. Konstaninos the Good. Now before starting this volume in earnest let’s look at how the empire got here…

------------------------------------------------------------

Emperors of Byzantium 1059-1085. From left to right is Konstaninos X Dukas, Michael VII Dukas, and Romanos IV Diogenes

Konstaninos X Dukas took the diadem after Isaakios Kommenos’s abdication. Quickly after he assumed power he raised his young sons Michael and Konstaninos to junior co-emperorships, and instituted a policy beneficial to the church and court bureaucracy. He revoked many of the necessary and important military reforms of Isaakios which led to the severe weakening and resentment of the army. He also disbanded large numbers of the standing army opting instead to replace it with mercenaries which would lead to, in part, the chaos after his death. In the 1060s the last strongholds of southern Italy fell to the Normans under Robert Guiscard, despite Konstaninos’s desperation to keep them. Though in 1067, he did try to reconquer Sicily, but upon his death it was recalled after capturing Syracuse.

Emperors of Byzantium 1059-1085. From left to right is Konstaninos X Dukas, Michael VII Dukas, and Romanos IV Diogenes

The young Michael VII Dukas was crowned senior emperor in 1067. Shortly after his coronation Michael was given an ultimatum by Romanos Diogenes. Romanos demanded senior co-emperorship with Michael, and the removal of Michael’s brother, junior emperor Konstaninos from the capitol. Michael fearing war with the powerful and popular Romanos quickly conceded giving his seven year old brother the title Kome’s of Syracuse. Early in his reign his uncle, Ioannes Dukas, attempted to usurp the throne from his significant lands in Bulgaria, but Romanos defeated and executed him in 1073. Around the same time Mihajlo Vojislavljevic invaded the Serbian Themes of the empire, and in 1075 slew Michael VII at the battle of Belgrade.

Romanos IV Diogenes became the sole senior emperor after Michael’s death in 1075. After hearing of Michael’s death, Alexios Komnenos rose in revolt with significant support throughout Anatolia and Armenia, along with the help of Mihajlo who at this time had just stormed Belgrade. Romanos then sent a mercenary army under the command of Romanos Argyros to put down the rebellion in its heartland, but after a secret meeting with Alexios the mercenary captains switched sides handing their commander over to Alexios. With his son as a hostage, Alexios forced Theodoros Argyros, Doux of Athens, to desert Diogenes’s cause, and join the Kommeni camp.

The Kommeni Rebellion after Theodoros’s defection Red stands for lands supporting the Kommeni and Purple are lands loyal to Diogenes.

Thus after 10 years of sporadic civil war, the Empire was at peace, though large portions of Anatolia still were only nominally subjected. For the next five years Romanos fought the large bands of lawless mercenaries who after being discharged from military service, plagued the countryside as bandits. He also restored the fleet that was cut in size under Konstaninos. A large portion of this new fleet was sent to Syracuse; where under the guardianship of the future Konstaninos XI they launched numerous raids against the Arabs and Italians. These raids would culminate in the battle of Cape Corse where the Byzantines heavily defeated an Italian coalition, and after extracting significant tribute returned in triumph to Syracuse. Sicily would also be the sight of the greatest triumph of Romanos’s reign. In 1084 the young Konstaninos Dukas, son of the late Konstaninos X and brother of Michael VIII, rapidly campaigned across Sicily. Konstaninos was able to seize Palermo in May, Agrigento in June, and Trapani in August. In little over a summer, the young man conquered a prize that had eluded Emperors for centuries. This would greatly improve Konstantinos’s popularity and fame among the commoners and nobles alike; during his triumph in Constantinople he was awarded the title Strategos of Sicily. In the last two years of his life Romanos having defeated the bandits raised a large veteran army, and marched along Anatolia forcing obedience to among the largely independent princes there. But in July 1085 a minor border incident with the Seljuk Turks spiraled out of control, and lead to Romanos declaring war. A week and a half later he was poisoned by person’s unknown thereby leaving his uncrowned, five year old son Stephanos in Constantinople.

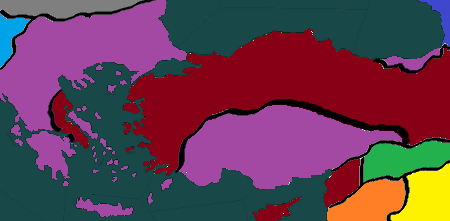

Byzantine Empire at Romanos’s death in 1085 also shown are the more independent Princes. Not shown is Sicily which is largely unified under Konstaninos Dukas.