End of an Auld Sang - 1426-1438

With the death of King Todos and the demise of the male line of the Qatwa dynasty, two primary claimants to the Assyrian throne emerged – both tracing their legitimacy through the three daughters of Niv III. The eldest, and by 1426 the only surviving, of the former King’s children was Princess Marte, who had been sent away in her youth to marry the English King of Sicily, bearing him two daughters who both died in infancy before political struggles on the island realm ousted her husband from power and sent her back into exile in Assyria, where she had absconded from politics and joined a nunnery. The candidate with the greatest support within the Kingdom was Dinkha Chahar Teghi, son of the respected Malik Rahim of Sinjar – one of the pious Nestorians who had participated in the killing of King Sabrisho’ alongside Todos – and Niv’s youngest, and by now deceased, daughter Morta. The greatest threat to Dinkha’s ascension to the crown came from outwith Assyria itself – to the Armenian ve Zhamo clan. Niv III’s second daughter, Shapira, had married the mercurial King Levon the Liberator of Armenia and birthed a brood of four sons and two daughters, before passing away following an outbreak of typhus – the eldest of which was Crown Prince Aboulgharib, the eldest grandson of Niv III and the figure with the strongest legal claim to the Assyrian inheritance

The tale of King Levon and the recent history of Armenia was in itself a captivating story of heroism and transformation. Through most of the Medieval period, as late as the early fourteenth century, there had been an independent Armenian Kingdom in the region around Lake Van. Although for almost a millennium from the nation’s conversion to Christianity, the Armenians had maintained an independent Apostolic Church, outwith the confines of Chalcedonian Christendom, the Middle Ages saw Byzantine influence encroach and Armenia’s Church enter into communion with Constantinople. The nation’s independent was brought to an end by the Mongol invasions of the Caucuses and eastern Anatolia in the first decades of the fourteenth century, with their homeland later passing over to the Timurids as the Iron Khan chased the Mongols north of the mountains at the end of the century. It was in this unstable context after the expulsion of the Mongols that a little known shepherd named Levon ve Zhamo came to attention. Abandoning his flock for a life of anti-Khazar banditry in the 1390s, Levon’s fame, prestige and ranks of followers quickly grew as he gained wealth and sparked a wave of revolt throughout the Armenian lands. By the turn of the century he controlled the lands around Lake Van and was already styling himself as King. Through the first decade of the 1400s, he continued his wars against the Timurids and his neighbours – pushing on to capture Yerevan, Tbilisi and Abkhazia and claiming the Kingship of Georgia.

As impressive as this rise had been, Levon was no mere warlord, and possessed both diplomatic cunning and a vision for religious reform. The titanic Christian empires that neighboured him to the south and west – Assyria and Byzantium – were both happy to see the Armenians give the Timurids a bloody nose and both sought to exert their influence. Levon played the two powers against one another, and achieved the legitimacy and geopolitical security he craved when Nechunya II of Assyria sent his sister Shapira to be his bride. Levon then embarked on his next great task – restoring the independence of the Armenian Apostolic Church under its traditional Oriental Orthodox doctrines. This dramatic reassertion of Church sovereignty has mixed results – drawing the largest part of the Armenian community within Levon’s realm to the new national Church, but creating a divide with the Armenian populations living within the Byzantine and Assyrian empire – whose populations largely ignored the change. Most immediately, Levon’s attempts to push Georgian Church – that had no history outwith Eastern Orthodoxy – to break its links with Constantinople and adopt Miaphysite doctrines led to civil war and rebellion. By 1420, Levon had lost all of his Georgian lands, although he continued to style himself as King of Armenia and Georgia, even if the latter was in name only.

King Todos’s poor health had been known for sometime prior to his death, and although he failed to designate a clear successor, the factions competing for the grand prize of the Assyrian throne had had plenty time to lay their plans. Upon the last Qatwa King’s death, the Armenians were quickest to react. Emphasising the seniority of Aboulgharib’s claim as the eldest male grandchild of Niv III, King Levon provided his son with a sizeable army and sent him to march south the claim his birth rite. In Nineveh, having only recently ejected the apostasy of Sabrisho’, the Assyrian nobility were in no mood for a heretical foreign to take power in their homeland and instead looked towards the Chahar Taghli family. With the teenage Dinkha installed on the throne, his father Rahim took charge of a powerful alliance that dominated Mesopotamia and the Gulf, although possessing weaker ties to the western Kingdoms.

Seeing the Assyrian heartland rally against him, Aboulgharib changed course away from Nineveh and instead marched westwards to Edessa. Taking advantage of alliances with the city’s large Armenian minority, the Prince took the city without a fight. There, he took the important political decision of turning away from the Oriental Orthodoxy of his father to embrace the Church of the East. This step saved his campaign from collapse. There were many magnates in opposition of Rahim and the Nineveh-faction who had been hesitant to align with the Armenians whose concerns were now eased, in particular the Maliks of Palmyra and Amman who had both been supportive of the short-lived policies of religious toleration under King Sabrisho’ and saw in Aboulgharib a tool with which to weaken the growing influence of Nestorian fundamentalism. With this, the Armenian Prince had established himself as a major force in the western provinces.

Aboulgharib’s presence in Edessa was far from universally welcomed in Syria. Despite his conversion to Nestorianism, he remained closely associated with his father’s campaign to re-establish Oriental Orthodoxy that had seen Greek Christian clergymen – Paulicians and Old Orthodox alike – denounce the ve Zhamos from the pulpit for decades. The threat of an Armenian takeover in Assyria therefore pushed the Greek Christian majority of north western Syria into revolt. The Greek Christian revolt turned Syria into the epicentre of the ensuing civil war as a three sided struggle emerged between the Syrian rebels, Aboulgharib and his Assyrian allies and Rahim’s forces.

The fighting was bitter and chaotic. In the east, Rahim brought sieges against Edessa and Palmyra, while engaging in raiding throughout the western provinces and seeking to attract allies to his cause. Yet the heaviest fighting was between the Armenian Prince and the Syrian rebels, with Greek Christians expanding their war by massacring the large Armenian minorities in the regions they controlled and pushing south from their core holdings around Aleppo and Antioch to attack key minority-populated territories in southern Syria home to the Messalians, Marionites and Druze. This struggle culminated in the decisive battle of Samsat in 1426, in which Aboulgharib led a veteran force to a great victory over a Syrian army twice its number.

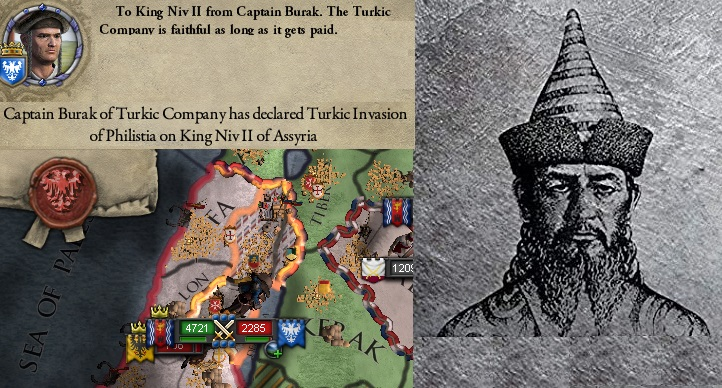

This important battlefield victory coincided with key diplomatic manoeuvres initiated by the wily old King Levon. Breaking off a proposed marriage to the Crown Prince of Alania, Levon offered the hand of his youngest daughter Sirvart to the Crusader King of Egypt, Simon, a man more than twice her age. As a behemoth among relative pygmies in Eastern Mediterranean Catholicism, Egypt held substantial cultural sway over the Cuman and Latin Catholic nobility of Philistia. The lords of the smallest of the Assyrian realms had sought to avoid committing heavily to any side in the civil war, with many considering a push for independence in the style of the Syrians. Yet the new connection forged between the Armenians and Alexandria, coupled with the tide of the war in the west appearing to turn in Aboulgharib’s favour after Samsat, convinced the Philistians to throw their lot in with his claim. Having already made alliances among the Marionites, Messalians and Druze through their mutual conflict against the Greek Christian Syrians, Aboulgharib had achieved a dominant position in the west. By the end of 1426, Syria and Philistia were firmly under his control, with Rahim withdrawing his armies towards the capital.

Aboulgharib invaded Mesopotamia in early 1427, confident of victory. Such was the Armenian’s momentum, Rahim chose to abandon the capital in order to withdraw deeper in an attempt to buy time. This gambit, although battering the confidence of his faction, proved a masterstroke. For more than a year the two armies parried back and forth, with Aboulgharib failing in every effort to push deeper into Mesopotamia. Finally, Rahim pinned his rival to a pitched battle at Samarra, vanquishing his force and sending him into a headlong retreat back to Syria – seeing Nineveh change hands once again. Receiving reinforcements from his father, the Armenian Crown Prince finally turned to stand his ground at the Battle of Darbasak, west of Edessa. In a close engagement, Aboulgharib came out with a clear battlefield advantage, forcing Rahim to abandon his push into Syria. Far more importantly, the would-be King Dinkha was captured on the field.

Dinkha was Rahim Chahar Teghi, and therefore the only alternative to the ve Zhamo clan who could trace their ancestry through the daughters of Niv III. Aboulgharib therefore offered his foes an amnesty. Should Rahim and his followers surrender and accept his ascension as King, and Dinkha renounce his royal pretensions and join the priesthood, Aboulgharib would allow his enemies to retain their titles, swear to the preservation of Church authority and provide positions of influence to his erstwhile enemies. Should they refuse, he would execute his imprisoned rival to the throne and continue to war to its bitter end. Malik Rahim took the fateful decision to accept peace, allowing Aboulgharib to return to Nineveh once more in 1429 where he was formally crowned King of Assyria, Syria and Philistia – marking the true birth of Assyria’s Armenian dynasty.

This might have been the end of the bloody succession struggle, but just as the conflict was dying down a third title claimant emerged in the deserts to the south. When King Sabrisho’ was overthrown 1422, remarkably just seven years before Aboulgharib’s final victory over Rahim Chahar Teghi, his young son Nerseh was believed to have been killed in the bloodshed the accompanied Todos’s palace coup. However, from the very first rumours had swirled, predominantly in the Muslim Belt of central Babylonia, that the young boy had been spared by supporters of his fallen father and spirited away to the friendly Muslim communities in the desert. During the late 1420s a boy in his early teenage years emerged in the heart of Arabia claiming to be the lost Prince Nerseh. Popular interest in the boy quickly grew, as a number of figures of Sabrisho’s regime began to claim that they could recognise him as the young child they had once known. He was drawn to the court of the Sulaymans in 1429, where the Sunni Caliph recognised him as the rightful successor of Sabrisho’, the last of the Qatwa, and the true King of Assyria. Seeing him as a tool with which the briefly promised Islamic resurgence in Assyria might be pursued, in 1430 the Caliph invaded the tired Assyrian realm in the name of Nerseh.

The Muslims made quick progress initially, finding largescale popular support among the Muslim communities living east of the Jordan in Philistia and, most potently, the Zikri of Babylonia. The Caliph had hoped than after half a decade of civil war, the Assyrian realm would be too weak and divided to offer a staunch resistance, yet his offensive only solidified Aboulgharib’s position by binding together the recently warring factions of Assyria’s political landscape against their shared infidel foe. The Caliph’s army was routed at Karbala in 1431, melting back into the Arabian Desert. However vicious fighting continued to roll on for years as Assyria’s Muslims fought to the end in the name of the supposed Prince Nerseh. In 1433, the Assyrian King launched a daring raid into the Nedjaz – receiving naval support in the Red Sea from Crusader Egypt – and successfully parleyed the surrender Nerseh in exchange for the safety of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Brought back to Assyria in chains, Nerseh was denounced as an imposter and a traitor and executed. Finally, the long battle for the Assyrian crown was over.

In 1438, the great King Levon of Armenia finally passed away after a remarkable life that had taken him from the humble beginnings among his sheep herds on the Armenian hillsides, to establish his progeny on the throne of a mighty empire. His death left Aboulgharib another inheritance, bringing the crowns of Armenia and Georgia into the sprawling collection of Assyrian dominions. He was now ruled a collection that contemporaries styled the Five Kingdoms – Assyria, Syria, Philistia, Armenia and Georgia. With the Armenian dynasty firmly secure in Assyria, and the union of their homeland with the Assyrian crown complete, a new age was dawning on the Near East.