From the journal of President Frederick William Wright:

Someone could rightly question the fact that I took time to write this account of the war while it is still ongoing. However, I suspect that very few accounts of these events will survive, so this may be the most important historical document in over 100 years. Also, writing this kind of journal does help me keep the big picture in mind.

Besides, there's a very good chance I won't be able to do it after the war.

When the attack first started, nobody knew what to expect. Some thought Cthulhu would immediately appear and crush the entire army in a day while others dreamed this would just be another conventional war between the two remaining nations. The truth ended up being somewhere in between: the day the attack started, a wave of dread and panic spread across our army, turning our careful plans into mass chaos. A few units had been chomping at the bit to attack since the end of the ritual, and the panic was enough to get them to go over the top. Their defeats were the opening battles of The War of Revelation.

My solution to this was to order even larger attacks. If we had to fight, we had better win. By mid-April, the tide was turning and we were pushing them back.

As President, I also had to worry about comparatively petty issues like the national budget. During the flurry of legislation after the ritual had finished, Higgins had signed the Industrialization Maintenance Act, which offered subsidies to factories that were facing bankruptcy because the global export markets had suddenly disappeared. While this did avert an economic collapse, it was now the nation's largest non-war expense. On April 21st, I signed a law ending all subsidies of private industry. Vital military industries could survive on war contracts and everything else was a luxury we could not afford. The unemployed could head to the front and pick up a rifle.

One of our ill-advised attacks was the army based in Bangor attacking into Fredericton.

However, General Potter managed to slip past the cultists to Prince Edward Island.

The rest of the offensive went well; we had far more men ready at the border than the cult did.

But the places the cultists wanted to hold on to, they kept.

At this point, we learned of another oddity. In many places where the United States army was once concentrated, we discovered ghost armies. These phantoms stood in perfect formation, doing nothing but unsettling us with their presence. We could do nothing but accept it as part of the chaotic world the cult ushered in.

By June, we had pushed the cult back at great loss of life.

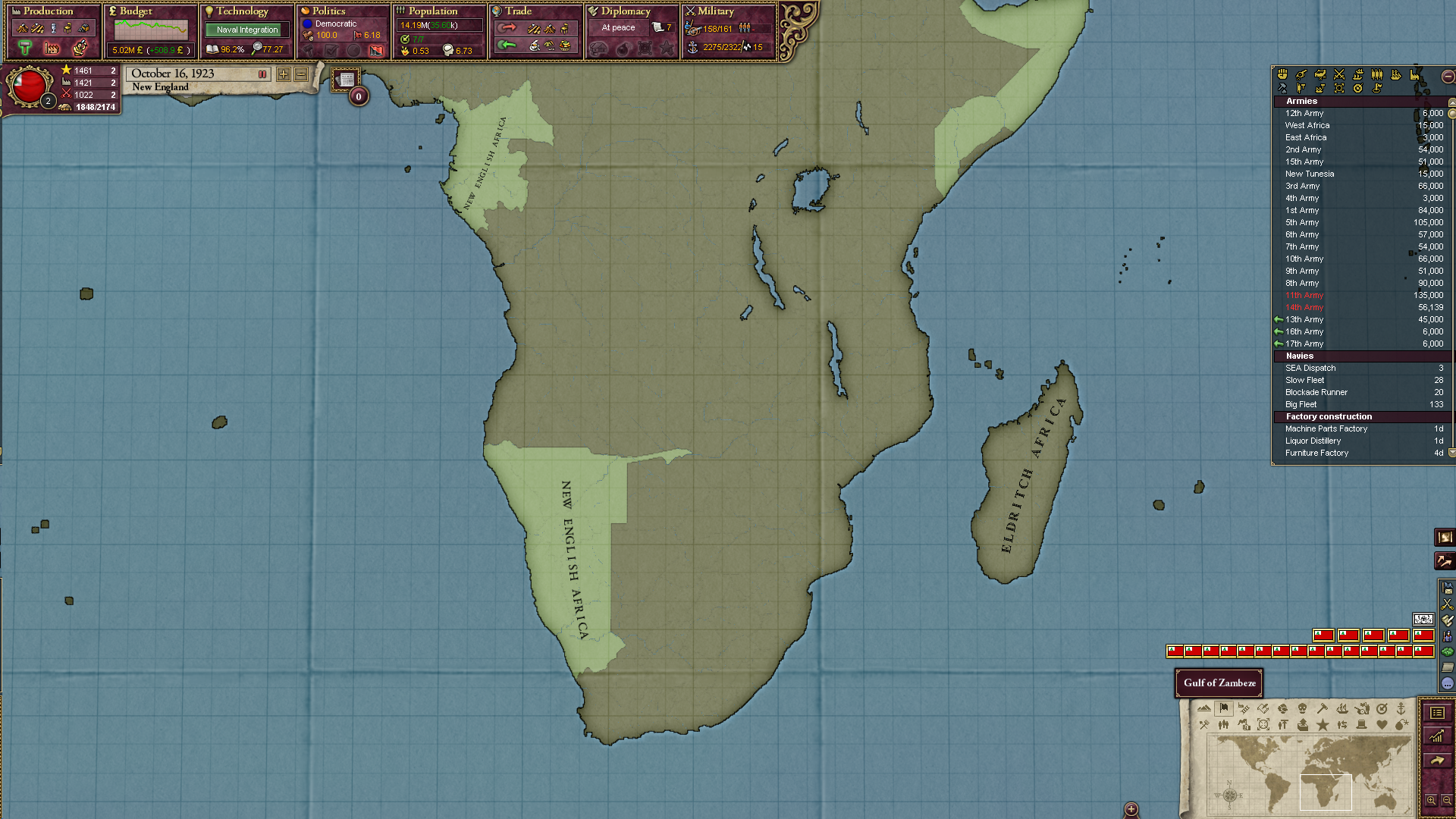

At this point, I was feeling good enough about our ability to hold New England that I was willing to send an invasion fleet across the Atlantic. We had no idea what they would find there, but the prospect of discovering a weakness in the enemy was enticing enough that we had to try.

Meanwhile, we invested more and more into Montreal.

By mid-July a New English force had once again pushed its way to the gates of London. Once again, a devoted but under-equipped cultist army was hellbent on stopping them.

On July 28th, the cultists in Montreal encircled our forces and we simply had no more troops in the area to break their lines. We had pushed our luck too far.

In late August, the same happened in a far more important city: London. Once again, we were outmanned and outgunned.

Neither of these battles were the end. Given its proximity to our major cities, Montreal was considered so vital that every army in the West and South was ordered to cross the country and defend it. Eventually, our sheer numbers forced the cult to make a tactical retreat.

As we were losing in London, a second expeditionary force was on its way. Exhausted from the first battle, the cultists retreated from London as well.

The general staff were pleased by this. One brigadier general boasted "They have a thousand times the men and guns we have. But ours are exactly where they need to be every time."

To our surprise, our attempt to take control of London was met with less resistance than it was during the First Eldritch War. The local population was still fanatically resisting, but there were far fewer of them this time around.

Meanwhile in Africa, the war was going exactly as expected; we were putting only enough resistance to slow them down and make taking the continent an expensive proposition.

As intelligence reports rolled in, we were pleased to learn that the cult had dedicated more men to this front than North America and Great Britain combined.

The abandoning of the West was not without its consequences.

In early October, we finally accomplished our main goal: the capture of London. What we found there was just about the only thing that possibly could have disappointed us: absolutely nothing. Within the improvised city walls was nothing but thousands of acres of ash left over from the largest sacrificial flame in human history. The center of their government and Cthulhu had long since evacuated. We still have not come into contact with either.

At this point, I took a moment to reflect on the war as a whole. We had lost many major battles, but we still had an intact army, and we were far from defeated.

As a side note, many in the State Department had gone mad, doing nothing but staring at a chart or map and repeating the word "France."

Throughout October, we were able to hold most of what we had, but advance no farther.

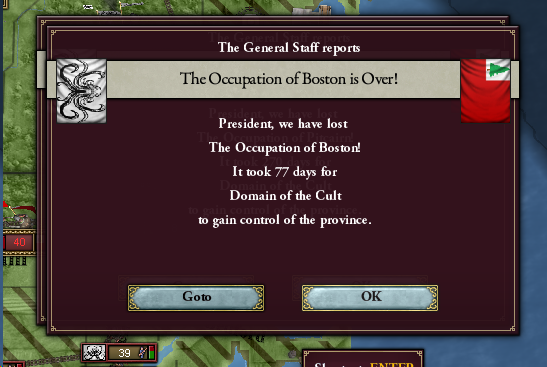

By November, the armies of the cult had come in earnest to retake their lost land. We had no way to stop them.

On November 8th, I made the decision to recall our expeditionary force from London to defend New England.

In December, our army attacked the largest individual attacking force the cult had in Plattsburgh.

Once again, our sheer manpower pushed them back into Canada.

One by one, our African colonies were falling.

But we still had a few pockets of control.

Despite our victory in Plattsburgh, the cult could not be stopped.

In a way, this was a microcosm of New England's entire history: we had a few glorious victories in battles while the cult quietly won the war.

In December 20th, our last outpost in the London fell, and the city was a silent ruin once again.

By January, it had become the army's official plan to defend only New England and Massachusetts and fight a guerrilla campaign everywhere else.

The few battles we did fight, we fought to win.

On January 18th, the survivors of the expeditionary force arrived in Boston, and the war entered a new phase.

In 1928, we would have no ambitions but to defend whatever we could and let everything else go.