Tilly hm? Interesting. Though he really should have made a stronger stand in that battle...like court martial his renegade commander.

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

RGB: No, they are not. Not at all. Chuck I will have to deal with the consequences of that, too.

stnylan: Yeah, the British military doesn't get to shine just yet. Don't worry, the glorious victories won't be too far in coming, though...

English Patriot: Ah, but Tilly still has an important part to play in British history. He'll be ridiculed, he'll be despised, but in the end he has his results, and those aren't limited to one battle in Germany where a suitable lightning rod for criticism was found...

canonized: Austria's rather busy being projected into by Switzerland at the moment.

CatKnight: Well, the general certainly didn't get out of it well. He's too much of James' friend, though, so he couldn't really touch him, but Erskine certainly isn't leading any armies from now on.

Next update will be Christmas themed, and will come (naturally ) on or just before Christmas.

) on or just before Christmas.

stnylan: Yeah, the British military doesn't get to shine just yet. Don't worry, the glorious victories won't be too far in coming, though...

English Patriot: Ah, but Tilly still has an important part to play in British history. He'll be ridiculed, he'll be despised, but in the end he has his results, and those aren't limited to one battle in Germany where a suitable lightning rod for criticism was found...

canonized: Austria's rather busy being projected into by Switzerland at the moment.

CatKnight: Well, the general certainly didn't get out of it well. He's too much of James' friend, though, so he couldn't really touch him, but Erskine certainly isn't leading any armies from now on.

Next update will be Christmas themed, and will come (naturally

I'm sad to see failure in Germany, but luckily battle in the Netherlands went better.

Olaus Petrus: Both ended up well in the end, which is what matters.

- - - - - - - -

The tradition of celebrating Christmas has always been a strong one in England. Early on, it was (as in Scandinavia) connected with the pagan winter festival of Yule (in Old English, geola); the Venerable Bede states that many pagan rituals were allowed to continue, though of course suitably Christianised. So important was this celebration that the entire month of December was, at the time, known as "yuletide". Our knowledge of these early celebrations is not very complete, but some parts are known (such as boar sacrifices with attendant feasting).

During the medieval period, a tradition developed of travelling around towns and cities, singing certain songs connected with Christmas. Developed from the European circle dance (the word carol comes from an old French word for such dances), they originally were extremely popular. They ranged from boisterous drinking songs, to this quite calm song from the 15th century:

Ic singe ane maegden

þat is maceless

Cyng ealle cyngas

to her Sun heo ceas

He cam eall swa stille

þer his moþer waes

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on þaet graes

He cam eall swa stille

to his moþers bur

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on se flor

He cam eall swa stille

þer his moþer lecg

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on se spreg

Moþer 7 maegden

waes nefer nan bute sce

Well swilc ane hlaefdige

Godes moþer be

One type of song popular in England, as in other areas, was the "macaronic" carol; one which switches in between Latin and the vernacular language. The height of this art form can be seen in Heinrich Suso's "In dulci jubilo", which switches seamlessly (and once in mid-line!) between Latin and German. A notable English version is the "Boar's Head Carol", from the 16th century. The song derives from the Yule boar sacrifice mentioned above, a tradition which survives both in the singing of this carol and in the popularity of ham as a Christmas meal.

Caput apri differo

Reddens laudens domino.

Þe bores heafd in hand bring I

Wiþ feldmaedder and beagas gey

I bide you eall sing mirrely

Qui estis in convivio

Þe bores heafd I do forstand

Is formost þaning in þis land;

Loc hwer efer it be fund

Servite cum cantico.

Be glad, hlafordes, boþ mor 7 less,

For þis haþ ordeynd ouer stiward

To heart you eall þis Cristemass

Þe bores heafd wiþ mustard.

The caroling tradition declined in the 16th and 17th centuries; music, especially outside of church services, was greatly discouraged by many Puritan groups, and it all but disappeared from cities. The 18th and 19th centuries saw a revival, especially after the legalisation of Catholicism saw them restarting what was for them an ancient and respected tradition. One of the more famous carols revived during this time is this one:

God rest ye mirry, eþelmenn, let noþing you dismey.

Aftmind Crist ouer Redder did com on Cristmass dey

To safe us all fram Satans pou'r hwan we were gan astray

REFRAIN:

O, tidings of elning and bliss, for Jesu Crist

Ouer Redder on Cristmass was yeborn.

In Beþlem, in Judeland, þis bless'd babe was yeborn,

And leid wiþ in a binn upon þis blessed morn,

For hwilc his moþer Mary did noþing tace in scorn.

REFRAIN

Fram God ou'r Heaf'nly Faþer a blessed angel came

And unto cuþly scepherds braght tidings of þe same:

How þat in Beþlem was yeborn þe Son of God by name.

REFRAIN

Nou to þe Lord sing hernesses, all you wiþin þis stead,

And efery oþer clasp you wiþ sooþly broþerhad,

Þis haly tide of Cristmass all oþer doþ bescade.

REFRAIN:

O, tidings of elning and bliss, for Jesu Crist

Ouer Redder on Cristmass was yeborn.

Like many other facets of English culture, caroling travelled to America as well. John Jacob Niles, in 1933, wrote (or collected) this carol, based off a song from the Appalachian region. One can see here the quite conservative nature of that dialect (even more so than normal for America).

I wondre as I wandre .out under þat suy,

Hou Jesu ouer redder .did com for to die,

For poor orn'ry people .lice þou and lice I.

I wondre as I wandre .out under þat suy.

Hwan Mary yebirþd Jesu .'twas in ane cous stall

Hwiþ scepherds and farmers .and wise menn and all.

And hih fram Gods heofen .a stars liht did fall

And þat behat of eldes .it þann did recall.

If Jesu he had wanted .for aniy wee þing,

Ane star in þat suy .or a bird on þe wing,

Or ell of Gods angels .in heof'n for to sing,

He siorly cold hafe it, .cause he waes þe cyng.

- - - - - - - -

Sources of the English Language, no. 8

Three Christmas carols

Three Christmas carols

The tradition of celebrating Christmas has always been a strong one in England. Early on, it was (as in Scandinavia) connected with the pagan winter festival of Yule (in Old English, geola); the Venerable Bede states that many pagan rituals were allowed to continue, though of course suitably Christianised. So important was this celebration that the entire month of December was, at the time, known as "yuletide". Our knowledge of these early celebrations is not very complete, but some parts are known (such as boar sacrifices with attendant feasting).

During the medieval period, a tradition developed of travelling around towns and cities, singing certain songs connected with Christmas. Developed from the European circle dance (the word carol comes from an old French word for such dances), they originally were extremely popular. They ranged from boisterous drinking songs, to this quite calm song from the 15th century:

Ic singe ane maegden

þat is maceless

Cyng ealle cyngas

to her Sun heo ceas

He cam eall swa stille

þer his moþer waes

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on þaet graes

He cam eall swa stille

to his moþers bur

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on se flor

He cam eall swa stille

þer his moþer lecg

as deaw in Aprele

þat fallþ on se spreg

Moþer 7 maegden

waes nefer nan bute sce

Well swilc ane hlaefdige

Godes moþer be

One type of song popular in England, as in other areas, was the "macaronic" carol; one which switches in between Latin and the vernacular language. The height of this art form can be seen in Heinrich Suso's "In dulci jubilo", which switches seamlessly (and once in mid-line!) between Latin and German. A notable English version is the "Boar's Head Carol", from the 16th century. The song derives from the Yule boar sacrifice mentioned above, a tradition which survives both in the singing of this carol and in the popularity of ham as a Christmas meal.

Caput apri differo

Reddens laudens domino.

Þe bores heafd in hand bring I

Wiþ feldmaedder and beagas gey

I bide you eall sing mirrely

Qui estis in convivio

Þe bores heafd I do forstand

Is formost þaning in þis land;

Loc hwer efer it be fund

Servite cum cantico.

Be glad, hlafordes, boþ mor 7 less,

For þis haþ ordeynd ouer stiward

To heart you eall þis Cristemass

Þe bores heafd wiþ mustard.

The caroling tradition declined in the 16th and 17th centuries; music, especially outside of church services, was greatly discouraged by many Puritan groups, and it all but disappeared from cities. The 18th and 19th centuries saw a revival, especially after the legalisation of Catholicism saw them restarting what was for them an ancient and respected tradition. One of the more famous carols revived during this time is this one:

God rest ye mirry, eþelmenn, let noþing you dismey.

Aftmind Crist ouer Redder did com on Cristmass dey

To safe us all fram Satans pou'r hwan we were gan astray

REFRAIN:

O, tidings of elning and bliss, for Jesu Crist

Ouer Redder on Cristmass was yeborn.

In Beþlem, in Judeland, þis bless'd babe was yeborn,

And leid wiþ in a binn upon þis blessed morn,

For hwilc his moþer Mary did noþing tace in scorn.

REFRAIN

Fram God ou'r Heaf'nly Faþer a blessed angel came

And unto cuþly scepherds braght tidings of þe same:

How þat in Beþlem was yeborn þe Son of God by name.

REFRAIN

Nou to þe Lord sing hernesses, all you wiþin þis stead,

And efery oþer clasp you wiþ sooþly broþerhad,

Þis haly tide of Cristmass all oþer doþ bescade.

REFRAIN:

O, tidings of elning and bliss, for Jesu Crist

Ouer Redder on Cristmass was yeborn.

Like many other facets of English culture, caroling travelled to America as well. John Jacob Niles, in 1933, wrote (or collected) this carol, based off a song from the Appalachian region. One can see here the quite conservative nature of that dialect (even more so than normal for America).

I wondre as I wandre .out under þat suy,

Hou Jesu ouer redder .did com for to die,

For poor orn'ry people .lice þou and lice I.

I wondre as I wandre .out under þat suy.

Hwan Mary yebirþd Jesu .'twas in ane cous stall

Hwiþ scepherds and farmers .and wise menn and all.

And hih fram Gods heofen .a stars liht did fall

And þat behat of eldes .it þann did recall.

If Jesu he had wanted .for aniy wee þing,

Ane star in þat suy .or a bird on þe wing,

Or ell of Gods angels .in heof'n for to sing,

He siorly cold hafe it, .cause he waes þe cyng.

Last edited:

Charles I

Born: 19 November 1600, Dunfermline, Fife

Married: Nicolette von Lothringen (on 25 February 1623)

Died: 12 August 1642, Keswick, Cumberland

Born: 19 November 1600, Dunfermline, Fife

Married: Nicolette von Lothringen (on 25 February 1623)

Died: 12 August 1642, Keswick, Cumberland

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain

King of Ireland [and France]

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

The prince must consider, as has been in part said before, how to avoid those things which will make him hated or contemptible; and as often as he shall have succeeded he will have fulfilled his part, and he need not fear any danger in other reproaches. It makes him hated above all things, as I have said, to be rapacious, and to be a violator of the property and women of his subjects, from both of which he must abstain.

-Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince

Any who had been paying attention would have shuddered upon the news that Charles had succeeded his father as Emperor of Great Britain. Most were not, however; it had been more than a decade since his older brother Henry had died and Charles had thus become heir to the throne, yet he was still a minor character in court. He was still an enigma in 1625, known only for being the king's son and for his celebrated marriage to a noble from the Palatinate, helping bring that country out from the French sphere of influence. A select few knew of his connections to the Duke of Buckingham; although nowhere near as close nor of a similar kind to those his father had, he was still well within Buckingham's sphere of influence.

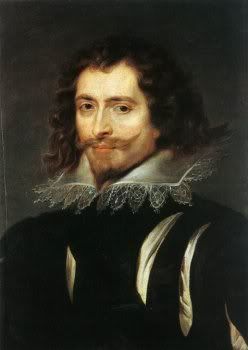

George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, by Peter Paul Rubens (1625)

Once he did come to the throne, however, people began to realise that something was wrong. While Buckingham was around, he seemed moderate enough, and quite a bit like his father. Away from the duke, however, he showed his true colours as an opponent of Parliamentary control, and of the Puritans in said Parliament. His first major action was, in 1626, to support an Anglican priest who had written pamphlets attacking Puritanism. Soon after, Buckingham, with Charles' approval, began a renewed campaign against Catholics in Ireland. This campaign was expensive, however, and Charles needed Parliament to approve money.

The legislature jumped at a chance to force Charles into compliance. In early 1628, it passed a petition of right, demanding several important points, mostly monetary, before any money would be given. Charles was in a tight spot, and therefore gave in. He hoped that the lack of such a distraction would allow him to quickly deal with Ireland, and then go back on his promise to uphold the petition once he could bring more force and influence to bear.

Before Ireland could be dealt with, however, tragedy struck. A Puritan soldier named John Felton, who had been wounded in an earlier battle in Connacht, approached Buckingham on 23 August 1628. With nobody else around, he pulled out a knife and fatally stabbed the duke, not making any effort to hide what he had done. In fact, he stated such out loud, and was immediately arrested, tried, and two months later, executed.

Soon after Buckingham's death, Ireland went into complete turmoil. Two uprisings in Munster during 1629 were bloodily put down, but Irish Catholics protesting the appearance of Scottish settlers in Ulster were able to take control of Belfast and most of the countryside. When the first army sent in was defeated, Charles decided to recall Tilly from Flanders and sent him to command. He reached Antwerp on 5 August 1629, but only five days later he was dead at the hand of a Brabantine Catholic. The loss of two of the most important British military commanders put the effort in Ireland behind, and it was not until October 1630, and intervention from Scottish regiments, that Belfast was retaken and the revolt put down.

Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, by Anthony van Dyck (1639)

Charles had one more man left to deal with the Irish. He sent the Earl of Strafford, a man who had already gained a reputation for unrelenting force. He was sent for one reason, to punish Ireland for being Catholic. If he proved successful, Charles intended to bring him back to England in order to do the same thing against the Puritans and Parliament.

Strafford despised the Irish, and spared nothing to keep them in line. Some of what he did was actually positive, but only to the Hiberno-English Protestants on the eastern half of the island. For the Catholics, they could only expect confiscation of lands and violence if they openly displayed their religion. For his part, he kept Ireland under control; there were no revolts after late 1631. Mostly, anyone who wished to revolt no longer had the financial basis to do so. He continued on Ireland for seven years, finally returning to England in 1639.

By that point, much had changed. Charles had dissolved Parliament, and began the "Personal Rule" of 11 years. During this time, he was able to keep from calling the body by using long-forgotten 13th and 14th century taxes, none of which were recieved well but all of which were completely legal. He also continued to oppose the Puritans, appointing the anti-Puritan William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury. An attempt by Puritan figure John Cotton to fight this only resulted in his imprisonment in 1634, and the departure of many important figures close to him (such as John Winthrop and Anne Hutchinson) to America, mostly the Bahamas.

What truly affected England was the start of the Helvetian War. The crisis had begun with a disagreement between the government of Siena and the Helvetian Confederation over certain border valleys. This soon brought in much of Italy on Siena's side, as well as France (with the famous Cardinal Richelieu hoping to extend French land in Italy) on Helvetia's side, on 1 May 1639. Charles was horrified at any expansion of French influence, and the King of Baden agreed. The latter declared war on Helvetia and France on 17 May, bringing in the Netherlands and Britain. Chalres was able to convince Austria to enter the war as well, completing the coalition against France.

Britain's border with France in Flanders gave them a specific role in the war, distracting the French armies in the north while Baden, Austria and the Italians dealt with the south. However, the Flemish theatre would prove to be much more hotly contested than this role would appear. Charles put into place the usual anti-French war plan, sending the fleet out into the Channel and thus keeping the French away. By 11 July, the Army of England was across the channel and besieging Calais.

As expected, the French army went on the offensive. Rather than engage them, however, the Army of Flanders held back and allowed them to besiege Luxemburg. The latter fell in December, while Calais was captured in February of 1640. As the French army moved north, the Flemish army was able to slip around Luxemburg and work towards recapturing it, while the English army advanced into Picardy. The British goal was now clear: trick the French into going after Brugge and Antwerp, while the English army cut off their supply lines.

Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of Luxemburg, by Henri Motte (1881)

The plan was working well enough until, in March, Poland and Magdeburg joined the war against Baden and Britain. The former immediately gave up Brandenburg rather than allow itself to be distracted, leaving the Polish to potentially transport an army over and cause trouble in Flanders. Charles refused to change the plan, even after a Polish army arrived in September and Brugge was besieged in August.

Luxemburg fell on 15 November and Arras on 15 December, and Charles' plan could finally be put into action. The two armies marched to meet near Antwerp, as the commander of the French army, the Duc d'Enghien, pulled back slightly when he realised what a position he was in (allowing the Poles to hold the siege with their sea-based supply line). They would never meet; the northern army reached Brugge on 12 January and defeated the Poles, while the southern army, under Ferdinand Fairfax, Lord of Cameron, reached Mesen and awaited the French counterattack. The battle that would come would be the deciding one in the Helvetian War.

And possibly the course of further events in England I would wager. The lustre of successful war can greatly aid a monarch's position. Defeat however tarnishes everything.

Hmm , the balance of power seems to be starting to formulate or at least we'll get to see the relative strength of the two heirs of the hundred years conflict . Here's me rooting for France .

Ah and so the French are on the move and stopping them could make or break the controversial King.

Probably break.

Probably break.

stnylan: Don't put too much emphasis on this, however; success in war can be ruined by poor domestic policy. Even a victory can be quite expensive...

canonized: They certainly have numbers and land technology on their side. And, looking at Richelieu in his armour there, a different sort of Panzerkardinal.

RGB: Again, don't put too much emphasis on this war...

- - - - - - - -

Update almost certainly tomorrow, I have the vast majority of it written. As a bonus, you get two battles, to make up for the near lack of them recently.

canonized: They certainly have numbers and land technology on their side. And, looking at Richelieu in his armour there, a different sort of Panzerkardinal.

RGB: Again, don't put too much emphasis on this war...

- - - - - - - -

Update almost certainly tomorrow, I have the vast majority of it written. As a bonus, you get two battles, to make up for the near lack of them recently.

Fairfax' army had altered an old castle at the border town of Mesen to be a useful fort. It controlled the road north from France back into Flanders; if the French wished to advance, they would have to take the fort, and defeat the British along with it. The man sent to do this was a rising young star in the French military: Louis de Bourbon, Duc d'Enghien and heir to the Prince of Conde. He was given 25,000 men for this purpose by the aging Cardinal Richelieu, against the British army of only around 17,000. D'Enghien was not too confident (he was far too intelligent a general for that), but he knew he had the better hand. There is little notably defensible terrain in that flat region, only streams aiding a defending army.

Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Conde, in an anonymous portrait

When the French arrived on 28 January 1641, they found the closest stream well to the south. As he came north, he found the British flanks apparently excellent pickings; the left flank was stronger thanks to the fort, but the right was all but hanging in the air. All military sense called for an attack there, and there was nothing d'Enghien could see to contradict this. However, he did not telegraph this; by all apperances, during the first advance he was moving to storm the fort and thus break the British army apart. Finally, after a short advance, he shifted his second line leftward to carry the main attack.

Unfortunately, things did not begin well for the plan. The original cavalry attack against the British right flank could not manage to get around, and was pushed back. Meanwhile, Fairfax pulled out his card: a large and highly mobile cavalry force, which overall numbered nearly half his army. The charge on the weakened French right flank was led by Fairfax' son, Thomas Fairfax; while the far right regiment of his army was commanded by another rising star, the immovable and able Oliver Cromwell, a lower gentleman from Huntingdon. His was a dangerous position, but Fairfax could count on him to stand as long as possible.

As d'Enghien's plan had to regain steam, Fairfax put his into full action. He had decided on a plan similar to that used by the late 4th century BC Greek general Demetrios Poliorcetes against the navy of the first Ptolemy. One flank, the apparently weaker, would draw the enemy to attack there. Meanwhile, the other flank would go on the attack, dispersing the enemy in front of them. By the time the weak flank was ready to retreat, the enemy would be under threat of being surrounded and thus forced to withdraw.

Both Demetrios in 307 BC and Fairfax in 1641 AD pulled it off almost flawlessly. The French right dissolved under the English attack, only managing to hold temporarily. By the time Cromwell's flank was outflanked and thus forced to withdraw, the younger Fairfax had pushed almost to the main road southward. D'Enghien knew immediately just how dangerous a position he was in. Further advancement forward would require moving into the city under the fire of the fort, while Fairfax' cavalry would be tearing apart his rear. The attack was called off, and d'Enghien focused on holding a secondary road southward. He had been defeated; a short standoff between two cavalry flanks ensured, but eventually Fairfax pulled back slightly and let the crippled French army retreat.

The Battle of Mesen. Each line is c. 1000 men.

With both King Louis VIII of France and Cardinal Richelieu ailing, their war effort was over. On 17 September, the French agreed to a cessation of hostilities against Britain and Baden, and a later peace treaty forbade any advancement into Italy. Later attempts in the 17th century would prove useless; French ambitions in that peninsula had been permanently dashed. Furthermore, the war spurred the French to build expensive fortifications along the border, which drained the treasury more than anything else. Although the Helvetian War would end well for its eponymous country, who expanded along the Alps into Austria, it was disastrous for the French.

The Polish were finally dealt with even easier. The British fleet soon made its way to the coast of Flanders, sweeping away any Polish ships in the area. The Poles, unable to continue operations in the area, agreed to give 240,000 pounds sterling as payment for Brandenburg. It wasn't much, but gave Charles a pretext for saying that this had been a victory as well, and had been a vindication of his strategy of controlling supply lines above all else.

Parliament did not agree with assigning Charles any praise for the war. 1640 and 1641 became important years, as Parliament demanded to sit again. Not willing to risk civil war while his army was away in France, Charles had to agree. When he brought Strafford back from Ireland, he only made matters worse. While Strafford's methods were, from a British perspective, all well and good against the Irish, they were unacceptable in England itself. On 25 November 1640, Strafford was arrested by Parliament. It took until 5 May 1641 for Parliament to agree to his execution; Charles wanted to strike back, but could not yet. Strafford was executed, a huge blow against Charles.

On 10 January 1642, Charles had had enough. He sent soldiers into the House of Commons to arrest five members he felt were the leaders of opposition to him; however, upon arriving, he found Parliament empty. Immediately after, Fairfax and his army declared in favour of Parliament, and Charles was forced to flee to the north, declaring Parliament and the army in rebellion. Civil war had struck the Empire of Great Britain.

It was over almost before it began. The army defected en masse to the Parliamentary side, leaving only the few thousand monarchists Charles could gather together. By late April, Charles' control of the country was limited to Northumberland. It was there that the only true battles of the Civil War occured. An excursion led by the elder Fairfax in early June was turned back at Marston Moor not far from York; in the end, he left the campaign to the younger Fairfax and Cromwell. By now, Cromwell was in command of one of the wings of the army, having gained the Fairfaxes' trust.

The Battle of Marston Moor, by J. Barker

The centre of the Royalist cause by this point was Carlisle; the two armies met not too far south of there, near the town of Keswick in the Lakes Region. Although Fairfax had the larger army, the Imperialist commander, Prince Rupert of the Rhine (younger brother of the Count Palatine), stood on a good position not far from the only nearby bridge across the River Derwent. He only gave enough room for Cromwell's division to deploy; there would rapidly be a backlog at the bridge. However, Cromwell had a plan to relieve this problem and give himself room to maneuver.

Before Rupert could react, Cromwell suddenly ordered his cavalry to shoot north into open space. Although this left the bridge crossing temporarily weakly covered, Fairfax, informed by a rider of Cromwell's plan, rushed soldiers across as quickly as possible to fill in the gap. Rupert was so caught off-guard that he was unable to quickly attack and take advantage of Fairfax' moment of weakness; by the time his men moved forward, they were already in a good position. More importantly, Cromwell had swung completely around Rupert's rapidly extending and thinning flank, and he then proceeded to roll it up.

Cromwell's target was none other than the Emperor himself. Charles was with the army, it being his only true protection, and suddenly Cromwell's cavalry bore down straight on him, outnumbering his guard two to one. Leaving most of them to hold the cavalry off, he fled as quickly as possible down the south road, hoping to escape into the mountains and out of Parliament's reach. Several thousand Imperialist soldiers were rushing south to escape Cromwell's rapidly closing trap, and Charles attempted to blend in with them.

He failed. Cromwell himself led a charge of several hundred cavalry straight into the mass, which Charles had only reached the edge of; the Emperor himself was struck by several bullets and killed, while Rupert was wounded and captured. Cromwell immediately swung about and escaped the angry Imperialist soldiers working to recover their ruler's body, quickly getting behind Fairfax' victorious divisions. With their Emperor dead, his heir only twelve, and their main commander captured, the Imperialist cause had fallen apart. Parliament now reigned supreme.

The Battle of Keswick. Each line is c. 1000 men.

Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Conde, in an anonymous portrait

When the French arrived on 28 January 1641, they found the closest stream well to the south. As he came north, he found the British flanks apparently excellent pickings; the left flank was stronger thanks to the fort, but the right was all but hanging in the air. All military sense called for an attack there, and there was nothing d'Enghien could see to contradict this. However, he did not telegraph this; by all apperances, during the first advance he was moving to storm the fort and thus break the British army apart. Finally, after a short advance, he shifted his second line leftward to carry the main attack.

Unfortunately, things did not begin well for the plan. The original cavalry attack against the British right flank could not manage to get around, and was pushed back. Meanwhile, Fairfax pulled out his card: a large and highly mobile cavalry force, which overall numbered nearly half his army. The charge on the weakened French right flank was led by Fairfax' son, Thomas Fairfax; while the far right regiment of his army was commanded by another rising star, the immovable and able Oliver Cromwell, a lower gentleman from Huntingdon. His was a dangerous position, but Fairfax could count on him to stand as long as possible.

As d'Enghien's plan had to regain steam, Fairfax put his into full action. He had decided on a plan similar to that used by the late 4th century BC Greek general Demetrios Poliorcetes against the navy of the first Ptolemy. One flank, the apparently weaker, would draw the enemy to attack there. Meanwhile, the other flank would go on the attack, dispersing the enemy in front of them. By the time the weak flank was ready to retreat, the enemy would be under threat of being surrounded and thus forced to withdraw.

Both Demetrios in 307 BC and Fairfax in 1641 AD pulled it off almost flawlessly. The French right dissolved under the English attack, only managing to hold temporarily. By the time Cromwell's flank was outflanked and thus forced to withdraw, the younger Fairfax had pushed almost to the main road southward. D'Enghien knew immediately just how dangerous a position he was in. Further advancement forward would require moving into the city under the fire of the fort, while Fairfax' cavalry would be tearing apart his rear. The attack was called off, and d'Enghien focused on holding a secondary road southward. He had been defeated; a short standoff between two cavalry flanks ensured, but eventually Fairfax pulled back slightly and let the crippled French army retreat.

The Battle of Mesen. Each line is c. 1000 men.

With both King Louis VIII of France and Cardinal Richelieu ailing, their war effort was over. On 17 September, the French agreed to a cessation of hostilities against Britain and Baden, and a later peace treaty forbade any advancement into Italy. Later attempts in the 17th century would prove useless; French ambitions in that peninsula had been permanently dashed. Furthermore, the war spurred the French to build expensive fortifications along the border, which drained the treasury more than anything else. Although the Helvetian War would end well for its eponymous country, who expanded along the Alps into Austria, it was disastrous for the French.

The Polish were finally dealt with even easier. The British fleet soon made its way to the coast of Flanders, sweeping away any Polish ships in the area. The Poles, unable to continue operations in the area, agreed to give 240,000 pounds sterling as payment for Brandenburg. It wasn't much, but gave Charles a pretext for saying that this had been a victory as well, and had been a vindication of his strategy of controlling supply lines above all else.

Parliament did not agree with assigning Charles any praise for the war. 1640 and 1641 became important years, as Parliament demanded to sit again. Not willing to risk civil war while his army was away in France, Charles had to agree. When he brought Strafford back from Ireland, he only made matters worse. While Strafford's methods were, from a British perspective, all well and good against the Irish, they were unacceptable in England itself. On 25 November 1640, Strafford was arrested by Parliament. It took until 5 May 1641 for Parliament to agree to his execution; Charles wanted to strike back, but could not yet. Strafford was executed, a huge blow against Charles.

On 10 January 1642, Charles had had enough. He sent soldiers into the House of Commons to arrest five members he felt were the leaders of opposition to him; however, upon arriving, he found Parliament empty. Immediately after, Fairfax and his army declared in favour of Parliament, and Charles was forced to flee to the north, declaring Parliament and the army in rebellion. Civil war had struck the Empire of Great Britain.

It was over almost before it began. The army defected en masse to the Parliamentary side, leaving only the few thousand monarchists Charles could gather together. By late April, Charles' control of the country was limited to Northumberland. It was there that the only true battles of the Civil War occured. An excursion led by the elder Fairfax in early June was turned back at Marston Moor not far from York; in the end, he left the campaign to the younger Fairfax and Cromwell. By now, Cromwell was in command of one of the wings of the army, having gained the Fairfaxes' trust.

The Battle of Marston Moor, by J. Barker

The centre of the Royalist cause by this point was Carlisle; the two armies met not too far south of there, near the town of Keswick in the Lakes Region. Although Fairfax had the larger army, the Imperialist commander, Prince Rupert of the Rhine (younger brother of the Count Palatine), stood on a good position not far from the only nearby bridge across the River Derwent. He only gave enough room for Cromwell's division to deploy; there would rapidly be a backlog at the bridge. However, Cromwell had a plan to relieve this problem and give himself room to maneuver.

Before Rupert could react, Cromwell suddenly ordered his cavalry to shoot north into open space. Although this left the bridge crossing temporarily weakly covered, Fairfax, informed by a rider of Cromwell's plan, rushed soldiers across as quickly as possible to fill in the gap. Rupert was so caught off-guard that he was unable to quickly attack and take advantage of Fairfax' moment of weakness; by the time his men moved forward, they were already in a good position. More importantly, Cromwell had swung completely around Rupert's rapidly extending and thinning flank, and he then proceeded to roll it up.

Cromwell's target was none other than the Emperor himself. Charles was with the army, it being his only true protection, and suddenly Cromwell's cavalry bore down straight on him, outnumbering his guard two to one. Leaving most of them to hold the cavalry off, he fled as quickly as possible down the south road, hoping to escape into the mountains and out of Parliament's reach. Several thousand Imperialist soldiers were rushing south to escape Cromwell's rapidly closing trap, and Charles attempted to blend in with them.

He failed. Cromwell himself led a charge of several hundred cavalry straight into the mass, which Charles had only reached the edge of; the Emperor himself was struck by several bullets and killed, while Rupert was wounded and captured. Cromwell immediately swung about and escaped the angry Imperialist soldiers working to recover their ruler's body, quickly getting behind Fairfax' victorious divisions. With their Emperor dead, his heir only twelve, and their main commander captured, the Imperialist cause had fallen apart. Parliament now reigned supreme.

The Battle of Keswick. Each line is c. 1000 men.

That was a rather swift revolution. I wonder how tyrannical the Parliamentary reign will be.

Well I was actually expecting a trial and execution for the King , but this seems to go along with the idea of a swift revolution indeed .

stnylan: You'll find out soon enough; I don't like to give out too many secrets before their time.

RGB: Hardly unprovoked! Charles has been abusing every facet of kingship during his reign, and Parliament isn't going to take it lying down, nor do they have to. Charles' list of crimes include:

Puritan theologians have developed a view of rulership in direct opposition to Charles' idea of divine right. It's taken from chapter 17 of Deuteronomy:

"Whom the LORD thy God shall choose": Must have certain traits associated with rulership, which Puritans would say have been given from God. Manifestations of divine wrath against the Emperor's person, property, or kingdom are to be taken as signs of divine disfavour with the ruler and thus grounds for removal. The ruler must be Christian and accepting of "correct" (i.e. Protestant) theology.

"One from among thy brethren shalt thou set king over thee: thou mayest not set a stranger over thee": Must be from one of the nations of Great Britain (English, Scottish, or Welsh). Cannot accept foreign titles without Parliamentary consent.

"But he shall not multiply horses to himself": The imperial cavalry guard must be kept at a small and fixed size. Breeding of horses for war is to be under Parliamentary supervision [thus the preponderance of cavalry in the Parliamentary army].

"Neither shall he multiply wives to himself": Must remain monogamous, and not take any mistresses. This, of course, falls under normal morality.

"neither shall he greatly multiply to himself silver and gold": The imperial budget is to be kept under strict control. Only a small proportion of taxes are allowed to go into the Emperor's treasury, and all taxes are to be raised only with Parliament's consent.

"And it shall be, when he sitteth upon the throne of his kingdom, that he shall write him a copy of this law in a book out of that which is before the priests the Levites: And it shall be with him, and he shall read therein all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the LORD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them": The Emperor must be knowledgeable in the Christian faith. Morality is not to be determined by the Emperor but by God, and Christ is the only supreme head of the English Church. The Emperor must promulgate only the Reformed Christian faith, allowing neither heresy nor Papism. Moral infractions by him are not to be tolerated.

"That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren": The Emperor is not above the law. He is to share authority with Parliament.

"To the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom:" Failure to follow this code or the general codes of morality are grounds for ending his reign. Divine wrath will descend upon the empire if an unsuitable man is kept as Emperor.

As for the speed, well, the nobility is almost entirely Parliamentarian. They see Parliament as their place to emphasise their rights in opposition to the Emperor. As such, they threw their weight against Charles. The army, also, is disproportionately Puritan, leaving Charles with precious few soldiers.

canonized: He's an Emperor. And don't worry, he'll still get a trial and execution. Ironically, not too far off from what happened to Cromwell historically.

RGB: Hardly unprovoked! Charles has been abusing every facet of kingship during his reign, and Parliament isn't going to take it lying down, nor do they have to. Charles' list of crimes include:

- Persecution of Puritans (Catholics too, but Parliament's okay with that)

- Dissolution of Parliament for eleven years, which is blatantly illegal in this history

- Direct taxation without the consent of Parliament (legal but greatly frowned upon)

- Supporting Strafford's abuse of freemen's rights in England

- Various forms of immoral behaviour (the rebels are Puritans, remember!)

- Use of a disproportionately Puritan army to arrest five Puritans (the immediate catalyst)

Puritan theologians have developed a view of rulership in direct opposition to Charles' idea of divine right. It's taken from chapter 17 of Deuteronomy:

"Whom the LORD thy God shall choose": Must have certain traits associated with rulership, which Puritans would say have been given from God. Manifestations of divine wrath against the Emperor's person, property, or kingdom are to be taken as signs of divine disfavour with the ruler and thus grounds for removal. The ruler must be Christian and accepting of "correct" (i.e. Protestant) theology.

"One from among thy brethren shalt thou set king over thee: thou mayest not set a stranger over thee": Must be from one of the nations of Great Britain (English, Scottish, or Welsh). Cannot accept foreign titles without Parliamentary consent.

"But he shall not multiply horses to himself": The imperial cavalry guard must be kept at a small and fixed size. Breeding of horses for war is to be under Parliamentary supervision [thus the preponderance of cavalry in the Parliamentary army].

"Neither shall he multiply wives to himself": Must remain monogamous, and not take any mistresses. This, of course, falls under normal morality.

"neither shall he greatly multiply to himself silver and gold": The imperial budget is to be kept under strict control. Only a small proportion of taxes are allowed to go into the Emperor's treasury, and all taxes are to be raised only with Parliament's consent.

"And it shall be, when he sitteth upon the throne of his kingdom, that he shall write him a copy of this law in a book out of that which is before the priests the Levites: And it shall be with him, and he shall read therein all the days of his life: that he may learn to fear the LORD his God, to keep all the words of this law and these statutes, to do them": The Emperor must be knowledgeable in the Christian faith. Morality is not to be determined by the Emperor but by God, and Christ is the only supreme head of the English Church. The Emperor must promulgate only the Reformed Christian faith, allowing neither heresy nor Papism. Moral infractions by him are not to be tolerated.

"That his heart be not lifted up above his brethren": The Emperor is not above the law. He is to share authority with Parliament.

"To the end that he may prolong his days in his kingdom:" Failure to follow this code or the general codes of morality are grounds for ending his reign. Divine wrath will descend upon the empire if an unsuitable man is kept as Emperor.

As for the speed, well, the nobility is almost entirely Parliamentarian. They see Parliament as their place to emphasise their rights in opposition to the Emperor. As such, they threw their weight against Charles. The army, also, is disproportionately Puritan, leaving Charles with precious few soldiers.

canonized: He's an Emperor. And don't worry, he'll still get a trial and execution. Ironically, not too far off from what happened to Cromwell historically.

Judas Maccabeus said:RGB: Hardly unprovoked!

Pish posh! He's their King! They're all traitors

It's always a pleasure to watch your animated battles, unrivaled in AARland. It's a quick revolution, that's for sure and I wonder if it means less dramatic change in England as a result. Would a Restoration be more palatable without a long protracted conflict?

Killing the king on battle, deposing monarchy... the your king will make an example of them in the future, for sure  Off with their heds, for a start...

Off with their heds, for a start...

Thanks, JM!  I am very grateful for this honor, to be added to the great crop of writers in the Tempus Society. It’s always a privilege to have your work recognized, especially when working on the same story for the past two years, with really no end in sight, hehe. It’s nice to take stock and appreciate how far you’ve come. Canonized loves a good speech and advised me not to fear a longer post, but I’ve recently been canonized by the namesake author, and these recent honors have left me less windy, I guess.

I am very grateful for this honor, to be added to the great crop of writers in the Tempus Society. It’s always a privilege to have your work recognized, especially when working on the same story for the past two years, with really no end in sight, hehe. It’s nice to take stock and appreciate how far you’ve come. Canonized loves a good speech and advised me not to fear a longer post, but I’ve recently been canonized by the namesake author, and these recent honors have left me less windy, I guess.

When I first encountered the Tempus Society, I thought it was some sort of AARland club for a select few. Then as I learned more about it, I realized it tries to do much of what I had secretly wished for this sub-forum: namely, recognizing old and young talent and bringing folks together from the many sub-forums and “eras” of writing. It helps foster enthusiasm for the forum, not simply because I add something to my signature and have a nice icon in my AAR (check it out, btw, first post, woohoo!)…ahem, but it has brought me into contact with writers I hadn’t heard of or only vaguely. So as much as I tout my original peers whenever I accept an honor, I have to acknowledge the “newbies” who impress me with their work as we speak: General_BT, rcduggan, English Patriot, to name a few. Thank you, subscription feature!

I love this forum. I can’t put it any simpler than that Where else could history buffs – and I mean insanely obsessed history buffs – gather together and not feel like an outsider, having to restrain one’s desire to just blab on and on about this year or date, this king or that, or that particular treaty. AARland has transformed me from a gamer who thought about writing into an actual writer. Thanks to canonized, JM, and others, who have recently reinvigorated my enthusiasm in this forum. And thanks again for this kind recognition. Right, not a long speech... ...back to your favorite JM programming...

...back to your favorite JM programming...

When I first encountered the Tempus Society, I thought it was some sort of AARland club for a select few. Then as I learned more about it, I realized it tries to do much of what I had secretly wished for this sub-forum: namely, recognizing old and young talent and bringing folks together from the many sub-forums and “eras” of writing. It helps foster enthusiasm for the forum, not simply because I add something to my signature and have a nice icon in my AAR (check it out, btw, first post, woohoo!)…ahem, but it has brought me into contact with writers I hadn’t heard of or only vaguely. So as much as I tout my original peers whenever I accept an honor, I have to acknowledge the “newbies” who impress me with their work as we speak: General_BT, rcduggan, English Patriot, to name a few. Thank you, subscription feature!

I love this forum. I can’t put it any simpler than that Where else could history buffs – and I mean insanely obsessed history buffs – gather together and not feel like an outsider, having to restrain one’s desire to just blab on and on about this year or date, this king or that, or that particular treaty. AARland has transformed me from a gamer who thought about writing into an actual writer. Thanks to canonized, JM, and others, who have recently reinvigorated my enthusiasm in this forum. And thanks again for this kind recognition. Right, not a long speech...

Having just skim-read through: great AAR! Very concise, a lot of information and extremely well-written. Goes straight in as my pick for EU1/2 History AAR in the AARland Choice Awards!

Here's hoping the monarchy manages to re-establish itself- I really want to see a Restoration Comedy in middle English !

!

Oh, and congratulations on the Tempus Society thing, Mettermrck!

Here's hoping the monarchy manages to re-establish itself- I really want to see a Restoration Comedy in middle English

Oh, and congratulations on the Tempus Society thing, Mettermrck!

Hurrah for Parliament! Caught up and glad to see things going well!

And Congrats Mettermrck

And Congrats Mettermrck