[Milites: Fortunately you'll be getting some more of that. We're getting some rather big developments indeed in this update!

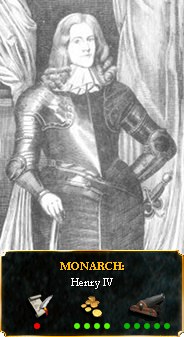

Morsky: You'll get to see just what his ineffectual son (with some rather ineffectual stats, as you can see) will do!

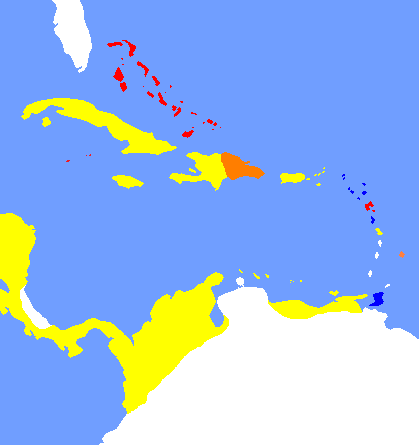

RGB: At least someone seems to be on our new ruler's side. Ollie had Penn shunted off to exile in America specifically so he wouldn't do anything, but since we'll be slipping in an American update soon you'll get your wish.

Ollie had Penn shunted off to exile in America specifically so he wouldn't do anything, but since we'll be slipping in an American update soon you'll get your wish.

Kurt_Steiner: You, on the other hand, get to keep waiting.]

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain (formerly Lord Protector of Great Britain)

King of Ireland [and France]

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Defender of the Elect within Great Britain and Ireland

Chancellor of the University of Oxford (to 1657)

One month after Oliver became Emperor, on 26 June 1657, the people of London crowded as well as they could to see his coronation procession. Preparations had already been underway before the Humble Petition had been passed, and even before Cromwell had agreed to the Imperial dignity; it was expected, that, if he had rejected it, an investiture ceremony would be held instead. That, of course, was no concern; the coronation continued as expected, though somewhat more subdued than previous coronations owing to Puritan influence. This did not, of course, prevent Oliver from appearing in proper Imperial regalia, though as most of the Crown Jewels had been lost or melted in the early Commonwealth some recasting and improvisation was necessary; only the Anointing Spoon, the Sword of Mercy, of Temporal Justice, and of Spiritual Justice survived. The Scottish crown jewels, still extant, were in Borcalan hands. The new crown made was itself simply a state crown, the only notable jewel set into it being the Duchess of Leinster's Ruby, which came into that venerable princess' possession in 1367 as a gift from the new king Menendo of Castile, a token of thanks for the de Cornouailles' support of his bid to that monarchy.

The Coronation Chair, by an anonymous engraver (1855)

King John's Chair, then still inset with the Stone of Scone, had also survived, but the traditional clerical hierarchy had not. Fortunately for Cromwell, the main legal viewpoint of the time, coming from Thomas Cranmer himself, was that the anointing by a bishop was not necessary; therefore, that portion of the ceremony was gracefully glossed over, though of course the supporters of the Borcalans were quick to note its omission. A great gold sceptre and the traditional newly-made ring completed the pomp of the ceremony. What it might have lacked in jewellery, however, was made up in the enthusiasm of those who crowded the streets to try and catch a glimpse of it. Cromwellian propaganda had been successful, despite the complaints from Levellers, in portraying the Instrument as a set legal defence of British liberty, and Oliver's new monarchy enjoyed broad popular support.

It soon began to collect a few noble supporters as well. Less than a month after the coronation, Oliver created his first new peer, Charles Howard becoming Viscount Morpeth; he also created several baronets in his early reign, notably a former Royalist, John Read, who had been appointed a Baronet by Emperor Charles in 1642, an appointment rejected by Parliament. The Petition had recreated the House of Lords, though at the time it was only called the Upper House. Convincing peers to return to the House was no easy task, especially as this version still contained commoners (the recluctant Charles Fleetwood among them). Slowly replacing the commoners with proper peers was no simple task, and was far from complete by the end of Oliver's reign.

Other minor difficulties had already arisen. An uprising by the natives across the British colonies along the southern Columbian coast was only a footnote, but the rift between John Lambert and the new Emperor was the main talk of Britain at the time. Lambert refused to take an oath of allegiance, and in return was deprived of his commission; Cromwell requested, and Parliament granted, a yearly pension of £2000. Lambert retired to the former royal manor at Wimbledon, and, importantly for the stability of the new regime, stayed ouf of political life for the time. One disaffected former supporter, however, was not so benign. In early 1657, a pamphlet, entitled "Killing no Murder", appeared in Britain under the pseudonym William Allen; the actual author was likely Colonel Silius Titus. It was not he who acted to commit the pamphlet's called-for assassination of Oliver, but a Leveller, Edward Sexby. He had taken part in earlier, similar plots, but his own attempt was in July of 1657. It, of course, failed, and Sexby was arrested and died in prison.

Ireland remained oddly quiet, partially thanks to the efforts of Oliver's younger son, Henry. The now-prince's policy in the region was surprisingly enlightened, not only keeping the peace among the various Protestant groups but in careful measures allowing the Catholics of the country a few lapses in enforcement. His wide popularity within Ireland slowly began to seep over into Britain itself, beginning to overshadow that of his undistiguished older brother, Richard. Many began to wonder whether Richard was truly suited to the Imperial throne, and noted that the Petition allowed Oliver to name a different successor than simply his first-born son.

If Oliver was debating a change in the succession, however, he never had an opportunity to put it into effect. In June of 1658, only little more than a year after having been given the Imperial throne, Oliver was struck with severe illness. He lingered for months, but finally, on 3 September 1658, he died of blood poisoning, leaving the throne to his son Richard.

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain (to 1659)

King of Ireland [and France] (to 1659)

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles (to 1659)

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland, Bretagne] (all to 1659) and York

Defender of the Elect within Great Britain and Ireland (to 1659)

Chancellor of the University of Oxford (to 1667)

The outcry that accompanied Richard to the British throne was surprisingly immense, even given the lack of support he had already entertained prior to his father's death. In all areas that those of the time could think of to judge a ruler by, they could find none which they considered good or even sufficient. He had likely never served in the army (some records state that he had during peaceful times in the late 1640s, but even that may be pure propaganda), had not administered any notable extent of land (the estate on which he lived belonged to his father-in-law, Richard Maijor), and had only served without any notable action in the two Protectorate Parliaments. Though he was called to the bar, he again had little to show for his legal profession, and few felt that this was enough to make for a proper ruler of an Empire that spanned so great an area of territory, especially with possible threats to its current state increasing every day.

John Lambert, who had begun reconciliation with Oliver not long before the latter's death, distanced himself from the new ruler, as did Richard's brother-in-law, Charles Fleetwood. The previous Parliament had ended, and the calling of another would require another round of elections, one that Richard would not well be able to control. The Puritan clergy did not feel that Richard had the piety or zeal of his father. All of this left him with no true base of power, a precarious position indeed. In more peaceful and prosperous times this would have been little trouble; but Richard had neither time nor resources to develop a base before problems arrived. Rumors reached the island daily of plans for invasion by Prince Charles, requiring a certain amount of constant readiness from the now-demoralised army. Said readiness did little good for the finances of the Empire, now running a debt for several years straight; a new Parliament was, in fact, called for early 1659 to fix these financial problems.

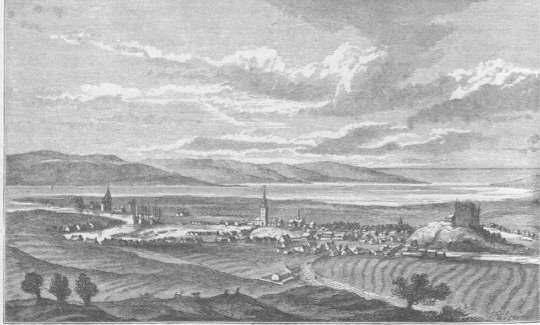

The Parliament that Richard got was all the more hostile. The large Republican minority decried the Imperial government itself, the Puritans decried his uncertain faith, the generals in the Upper House decried his lack of experience, and some dropped very careful hints that they might prefer Charles Borcalan on the throne to him after all. A fire that badly damaged Inverness on 10 February 1659 only worsened matters as Richard recommended further spending to replace the city's infrastructure. Parliament accepted this last matter, warily, but refused to pay for the army and asked that it be cut back. Oddly enough, this bit gave Richard some relief - it turned the army's anger away from him and towards Parliament, especially as Richard had spoken up in favour of the military's power - but the entire matter destroyed the last hope he had in building any sort of power.

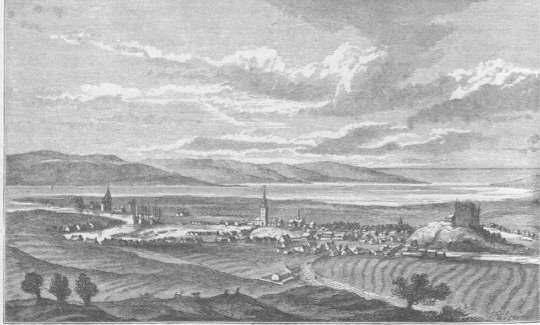

17th-centry Inverness, as rebuilt after the fire

As winter turned to spring, the rift between the army and Parliament threatened again to turn into civil war. On 12 April 1659, Parliament impeached Major-General William Boteler, accused of mistreatment of a Protestant prisoner, and a few days later forbade any councils of officers to meet without the Emperor's permission. The army, in response, demanded that the Emperor dissolve Parliament; Richard responded, simply, that the Instrument required Parliament to sit for five months, and refused. In response, portions of the army assembled and threatened to return the old Rump Parliament to power by force.

In the space of a month, Richard made the two bravest decisions of his life. The first was on 22 April, when the units of the army moved into London to make good on their threat to dissolve Parliament. Richard, having been well advised on which portions of his personal guard were not in sympathy with the army, put these loyal force into place to defend Parliament, and then brought out the piece of propaganda needed to end the situation. Noting to the populace that the army was intent on, in his view, being rid of the popular Instrument and return to military dictatorship, he managed to get into place a decent amount of irregular civilians armed with what was available. While this force would not likely have been sufficient to win a battle, it was enough to convince the army that this action would lead to large portions of Britain rising up in revolt against them. It was a bluff - Richard could not count on any further support than what he already had - but it was an effective one, buying him enough time to organise his other decision.

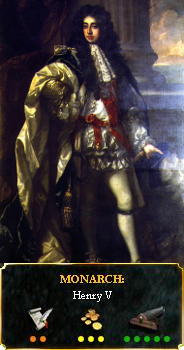

Richard knew that his days on the throne were numbered. The next month was a feverish one - preparations were made, Richard's much more popular and persuasive brother Henry was recalled from Ireland to support him, and negotations went on with Parliament. On 25 May 1659, after Parliament agreed to his details and after the vital smooth transition was ensured, Richard abdicated the throne in favour of his brother, who became Emperor Henry IV with Parliament's relieved and hopeful acclaim.

Morsky: You'll get to see just what his ineffectual son (with some rather ineffectual stats, as you can see) will do!

RGB: At least someone seems to be on our new ruler's side.

Kurt_Steiner: You, on the other hand, get to keep waiting.]

Oliver Cromwell

Born: 25 April 1599, Huntingdon, East Anglia

Married: Elisabeth Bourchier (on 22 August 1620)

Died: 3 September 1658, London

Born: 25 April 1599, Huntingdon, East Anglia

Married: Elisabeth Bourchier (on 22 August 1620)

Died: 3 September 1658, London

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain (formerly Lord Protector of Great Britain)

King of Ireland [and France]

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Defender of the Elect within Great Britain and Ireland

Chancellor of the University of Oxford (to 1657)

"And it is said that when he took his seat for the first time under the golden canopy on the royal throne, Demaratus the Corinthian, a well-meaning man and a friend of Alexander's, as he had been of Alexander's father, burst into tears, as old men will, and declared that those Hellenes were deprived of great pleasure who had died before seeing Alexander seated on the throne of Dareius."

- Plutarch, Life of Alexander

One month after Oliver became Emperor, on 26 June 1657, the people of London crowded as well as they could to see his coronation procession. Preparations had already been underway before the Humble Petition had been passed, and even before Cromwell had agreed to the Imperial dignity; it was expected, that, if he had rejected it, an investiture ceremony would be held instead. That, of course, was no concern; the coronation continued as expected, though somewhat more subdued than previous coronations owing to Puritan influence. This did not, of course, prevent Oliver from appearing in proper Imperial regalia, though as most of the Crown Jewels had been lost or melted in the early Commonwealth some recasting and improvisation was necessary; only the Anointing Spoon, the Sword of Mercy, of Temporal Justice, and of Spiritual Justice survived. The Scottish crown jewels, still extant, were in Borcalan hands. The new crown made was itself simply a state crown, the only notable jewel set into it being the Duchess of Leinster's Ruby, which came into that venerable princess' possession in 1367 as a gift from the new king Menendo of Castile, a token of thanks for the de Cornouailles' support of his bid to that monarchy.

The Coronation Chair, by an anonymous engraver (1855)

King John's Chair, then still inset with the Stone of Scone, had also survived, but the traditional clerical hierarchy had not. Fortunately for Cromwell, the main legal viewpoint of the time, coming from Thomas Cranmer himself, was that the anointing by a bishop was not necessary; therefore, that portion of the ceremony was gracefully glossed over, though of course the supporters of the Borcalans were quick to note its omission. A great gold sceptre and the traditional newly-made ring completed the pomp of the ceremony. What it might have lacked in jewellery, however, was made up in the enthusiasm of those who crowded the streets to try and catch a glimpse of it. Cromwellian propaganda had been successful, despite the complaints from Levellers, in portraying the Instrument as a set legal defence of British liberty, and Oliver's new monarchy enjoyed broad popular support.

It soon began to collect a few noble supporters as well. Less than a month after the coronation, Oliver created his first new peer, Charles Howard becoming Viscount Morpeth; he also created several baronets in his early reign, notably a former Royalist, John Read, who had been appointed a Baronet by Emperor Charles in 1642, an appointment rejected by Parliament. The Petition had recreated the House of Lords, though at the time it was only called the Upper House. Convincing peers to return to the House was no easy task, especially as this version still contained commoners (the recluctant Charles Fleetwood among them). Slowly replacing the commoners with proper peers was no simple task, and was far from complete by the end of Oliver's reign.

Other minor difficulties had already arisen. An uprising by the natives across the British colonies along the southern Columbian coast was only a footnote, but the rift between John Lambert and the new Emperor was the main talk of Britain at the time. Lambert refused to take an oath of allegiance, and in return was deprived of his commission; Cromwell requested, and Parliament granted, a yearly pension of £2000. Lambert retired to the former royal manor at Wimbledon, and, importantly for the stability of the new regime, stayed ouf of political life for the time. One disaffected former supporter, however, was not so benign. In early 1657, a pamphlet, entitled "Killing no Murder", appeared in Britain under the pseudonym William Allen; the actual author was likely Colonel Silius Titus. It was not he who acted to commit the pamphlet's called-for assassination of Oliver, but a Leveller, Edward Sexby. He had taken part in earlier, similar plots, but his own attempt was in July of 1657. It, of course, failed, and Sexby was arrested and died in prison.

Ireland remained oddly quiet, partially thanks to the efforts of Oliver's younger son, Henry. The now-prince's policy in the region was surprisingly enlightened, not only keeping the peace among the various Protestant groups but in careful measures allowing the Catholics of the country a few lapses in enforcement. His wide popularity within Ireland slowly began to seep over into Britain itself, beginning to overshadow that of his undistiguished older brother, Richard. Many began to wonder whether Richard was truly suited to the Imperial throne, and noted that the Petition allowed Oliver to name a different successor than simply his first-born son.

If Oliver was debating a change in the succession, however, he never had an opportunity to put it into effect. In June of 1658, only little more than a year after having been given the Imperial throne, Oliver was struck with severe illness. He lingered for months, but finally, on 3 September 1658, he died of blood poisoning, leaving the throne to his son Richard.

- - - - - - - -

Richard I Tumbledown

Born: 4 October 1626, Huntingdon, East Anglia

Married: Dorothy Maijor (on 1 May 1649)

Died: 12 July 1712, Hursley, Hampshire

Richard I Tumbledown

Born: 4 October 1626, Huntingdon, East Anglia

Married: Dorothy Maijor (on 1 May 1649)

Died: 12 July 1712, Hursley, Hampshire

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain (to 1659)

King of Ireland [and France] (to 1659)

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles (to 1659)

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland, Bretagne] (all to 1659) and York

Defender of the Elect within Great Britain and Ireland (to 1659)

Chancellor of the University of Oxford (to 1667)

"I have delivered my Son up to you; and I hope you will counsel him: he will need it;"

- Oliver Cromwell, in a letter to Richard Maijor (19 July 1649)

The outcry that accompanied Richard to the British throne was surprisingly immense, even given the lack of support he had already entertained prior to his father's death. In all areas that those of the time could think of to judge a ruler by, they could find none which they considered good or even sufficient. He had likely never served in the army (some records state that he had during peaceful times in the late 1640s, but even that may be pure propaganda), had not administered any notable extent of land (the estate on which he lived belonged to his father-in-law, Richard Maijor), and had only served without any notable action in the two Protectorate Parliaments. Though he was called to the bar, he again had little to show for his legal profession, and few felt that this was enough to make for a proper ruler of an Empire that spanned so great an area of territory, especially with possible threats to its current state increasing every day.

John Lambert, who had begun reconciliation with Oliver not long before the latter's death, distanced himself from the new ruler, as did Richard's brother-in-law, Charles Fleetwood. The previous Parliament had ended, and the calling of another would require another round of elections, one that Richard would not well be able to control. The Puritan clergy did not feel that Richard had the piety or zeal of his father. All of this left him with no true base of power, a precarious position indeed. In more peaceful and prosperous times this would have been little trouble; but Richard had neither time nor resources to develop a base before problems arrived. Rumors reached the island daily of plans for invasion by Prince Charles, requiring a certain amount of constant readiness from the now-demoralised army. Said readiness did little good for the finances of the Empire, now running a debt for several years straight; a new Parliament was, in fact, called for early 1659 to fix these financial problems.

The Parliament that Richard got was all the more hostile. The large Republican minority decried the Imperial government itself, the Puritans decried his uncertain faith, the generals in the Upper House decried his lack of experience, and some dropped very careful hints that they might prefer Charles Borcalan on the throne to him after all. A fire that badly damaged Inverness on 10 February 1659 only worsened matters as Richard recommended further spending to replace the city's infrastructure. Parliament accepted this last matter, warily, but refused to pay for the army and asked that it be cut back. Oddly enough, this bit gave Richard some relief - it turned the army's anger away from him and towards Parliament, especially as Richard had spoken up in favour of the military's power - but the entire matter destroyed the last hope he had in building any sort of power.

17th-centry Inverness, as rebuilt after the fire

As winter turned to spring, the rift between the army and Parliament threatened again to turn into civil war. On 12 April 1659, Parliament impeached Major-General William Boteler, accused of mistreatment of a Protestant prisoner, and a few days later forbade any councils of officers to meet without the Emperor's permission. The army, in response, demanded that the Emperor dissolve Parliament; Richard responded, simply, that the Instrument required Parliament to sit for five months, and refused. In response, portions of the army assembled and threatened to return the old Rump Parliament to power by force.

In the space of a month, Richard made the two bravest decisions of his life. The first was on 22 April, when the units of the army moved into London to make good on their threat to dissolve Parliament. Richard, having been well advised on which portions of his personal guard were not in sympathy with the army, put these loyal force into place to defend Parliament, and then brought out the piece of propaganda needed to end the situation. Noting to the populace that the army was intent on, in his view, being rid of the popular Instrument and return to military dictatorship, he managed to get into place a decent amount of irregular civilians armed with what was available. While this force would not likely have been sufficient to win a battle, it was enough to convince the army that this action would lead to large portions of Britain rising up in revolt against them. It was a bluff - Richard could not count on any further support than what he already had - but it was an effective one, buying him enough time to organise his other decision.

Richard knew that his days on the throne were numbered. The next month was a feverish one - preparations were made, Richard's much more popular and persuasive brother Henry was recalled from Ireland to support him, and negotations went on with Parliament. On 25 May 1659, after Parliament agreed to his details and after the vital smooth transition was ensured, Richard abdicated the throne in favour of his brother, who became Emperor Henry IV with Parliament's relieved and hopeful acclaim.