CHAPTER I – THE RETURN OF ARTHUR

The Christmas feast of 1066 at the stronghold of Aberffraw on the isle of Ynys Môn was no different than any before, except for the political changes that had swept Lloegyr in this same year. The only thing of note beyond the usual carousing, vomiting, fist-fights, and gossiping was that the Prince, Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, had wandered out of the great hall toward the sea-shore alone. Even his guards supposed that he was just feeling his ale and needed the salty air to sober up before going to bed. Instead, an hour later, he ran into the hall laughing, waving a 3 ½ foot long sword above his head and telling every soul how he had seen King Arthur and was blessed to conquer all Britain. At first, his drunken companions laughed, but upon inspecting the sword more closely, they fell silent. It was not “modern” but of a clearly antique make, perhaps a Roman cavalry sword of the 5th century? It certainly did not match any type the battle-hardened warriors of Gwynedd had ever seen. Bleddyn exclaimed “Excalibur,” and that was it. The entire hall sobered and praised God for this blessing. The deliverance of Britain was at hand.

WEST BRITAIN IN THE 11th CENTURY

Western Britain was, much like neighboring Ireland, still divided between several petty princes at the time of the Norman Conquest. This was a recent situation, however, and the fault of (surprise) Saxon interference. Gruffydd ap Llywelyn (r. 1055-1064), “King of the Britons,” was able to make himself king of most of Wales by 1055 and also held parts of England near the border after several victories over English armies. However in 1063 he was defeated by Harold Godwinson and killed by his own men.

Following Gruffydd's death, Harold married his widow Ealdgyth, though she was to be widowed again three years later. Gruffydd's realm was divided again into the traditional kingdoms. Bleddyn ap Cynfyn and his brother Rhiwallon came to an agreement with Harold and were given the rule of Gwynedd and Powys. Thus when Harold was defeated and killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the Normans reaching the borders of West Britain were confronted by the traditional kingdoms rather than a single king. Bleddyn now created the

casus belli with which to reverse this, reuniting the British realm and concentrate on foiling the Norman threat.

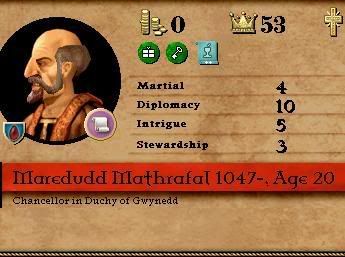

BLEDDYN

Fig. 1 - Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, King of Gwynedd

So who was this man that made himself the heir of Arthur on that cold night in 1066? He was the son of Princess Angharad ferch Maredudd (of the Dinefwr dynasty of Deheubarth) with her second husband Cynfyn ap Gwerstan, a noble from the Kingdom of Powys, about whom little is now known. Many have theorized that he may have been son of an English Saxon; the name has been postulated as being derived from

Werestan. His mother Angharad was previously widow of Llywelyn ap Seisyll and mother of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn.

When Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was killed, his realm was divided among several British Princes. Bleddyn and his brother Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn, as half brothers to Gruffudd succeeded to his lands; first as vassals and allies of the Saxon King of England, Edward the Confessor, and then submitted to Harold and from him received Gwynedd and Powys respectively.

Fig. 2 - Bleddyn's vassals: Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn, Prince of Powys and the King's brother, and Edwyn, Prince of Perfeddwlad

In his personal character, there was nothing extraordinary, good or evil, or any great genius. He was a typical representation of a warrior-aristocracy in the 11th century British Isles. He can be said to have had an uncanny ability to strike at the right time almost every time, both in external adventures and internal politics. The

Brut y Tywysogion also paints him to have been a benevolent ruler:

... the most lovable and the most merciful of all kings ... he was civil to his relatives, generous to the poor, merciful to pilgrims and orphans and widows and a defender of the weak ...

The mildest and most clement of kings... and he did injury to none, save when insulted... openhanded to all, terrible in war, but in peace beloved.

GWYNEDD’S POSITION

Fig. 3 - Britain in 1066 [Gwynedd = white, Saxon allies = blue, independent British rulers = black, Deheubarth (claimed by Bleddyn) = grey]

The Kingdom of Gwynedd was afforded a wonderful position to spoil the progress of William the Conqueror’s subjugation of England. William had only been able to secure and place Norman rulers in the south, while north of the Humber remained on the firm control of the Saxon House of Leofricsson. These nobles had already pledged featly to William at his coronation that Christmas, but were soon planning a massive uprising to, at least, secure their independence. Bleddyn had nothing to gain from that, but uniting with the Saxons to break Norman power was to his advantage, so he maintained his alliance with the Earls of Northumberland and Lancaster and ever sought to strengthen them with several marriages between the two houses (with vary success in getting them).

Scotland, looming over the north, was a powerful kingdom, but Malcolm I refused to be drawn into the British-Saxon intrigues against his new southern neighbor. The envoys of Bleddyn were constantly refused in attempts of gain a bride of the royal line or to gain an alliance against the Norman. Scotland still lay under the shadow of the Norse threat along with the rebelliousness of her own Highland nobility.

West Britain itself was divided, but this turned out not to be as great a problem as one would think. Only the Kingdom of Deheubarth, ruled by Bleddyn’s maternal cousin Maredudd, actually stood as an open rival. As time would prove, the Princes of Gwent and Morgannwg, already on good terms with Bleddyn, would willing come under his rule in order to avoid being gobbled up by the expansionist Normans.

WHY ARTHUR?

In the midst of this, why did Bleddyn feel the need to resurrect Arthur? If he needed backing to his claim to be ruler of a united West Britain, he had enough via his mother’s blood. Most of the men in the last fifty years who had united the country were related to him by her in one way or another. If he needed to find support for his plans to join the Saxons in a general war against the Normans, it should not have been necessary, as the aggressive nature of England’s new masters was naked, a plain threat to every native ruler on the island. So why the visions of Arthur by the sea, Excalibur, and pretensions to Camelot, what was the point of it?

It was more than grand propaganda and just a small piece in a greater picture of what should be called the “First Great Arthurian Mania.” The shock of Hastings was its trigger, as story-tellers (both British and Saxon) saw the parallel between this new invasion and that of the Saxons which engulfed old Britain five hundred years before. In the courts of the British princes the bards sung the old tales; Arthur’s hunting of the great boar, Twrch Trwyth, his conversation with the shape-shifting gatekeeper, his journey to the Underworld, the tales of the fights of he and his 200 “knights,” his great feasts at Caerleon, and the twelve battles in which he defeated and drove the Saxons from Britain (Saxon bards, naturally, twisted these, resulting in the later tales of Arthur fighting rival kings instead of German invaders). The later additions made by Geoffrey of Monmouth, like Arthur’s war against Rome, were not around yet, but the iconic hero was already there. Britain needed a hero, especially one to complete with cunning of William of Normandy. While Arthur himself would not arise and return from Avalon to save his beleaguered countrymen, Bleddyn clearly and openly put that mantle upon himself and his successors.