Shield of the West: Reign of Manouel II

The warmth of the burning yellow sun that gently sat in the clear blue sky gleamed down on a modest house near the center of Constantinople. It was a beautiful day, as the birds happily sang upon the windowsills of the many houses that lined the quiet neighborhood. A gentle breeze blew through the air, offering relief from the summers heat. It was a day when most were out shopping for goods in the City’s many markets, or simply enjoying the day with their families and loved ones.

Within this modest house however was one man who was more than content to enjoy the lovely day in solitude, with only the company of his books and his trusted quill to pass the time. Yes, rather than spend the day idly staring at the sky, Georgios Frantzis would continue his life’s work in this rare moment of free time.

The Emperor had left the City only yesterday for a diplomatic visit to Florence, Italy. He had hoped to garner the support of the Papacy against the increasingly aggressive incursions into the Empire’s northern territories by the Kingdom of Hungary. This offered Georgios a rare break from his busy life as head chamberlain at the Emperor’s residence. He was determined to use this time wisely, for perhaps if he was quick, he could complete his tome by the time the Emperor returned.

Seated at his desk and with his favorite quill in hand, the aspiring historian diligently set about the task of writing the third volume of his history of the Laskarid Dynasty…

Manouel II Laskaris, crowned in the Hagia Sophia on the 24th of September 1313, was the eldest of Ioannes IV’s three sons. Growing up during a period of constant warfare in the Empire, the 34 year old Emperor had already seen many battles, and had lead his share of campaigns against the Turkish hordes in the east, proving himself to be a capable commander who was able to inspire his men to victory even when the odds favored the enemy. Like his father, he enjoyed the wide support of the army, and many of his most trusted companions were present at his coronation.

Being the first Emperor to be born after the liberation of Constantinople, he generally held a softer view of the Latin schismatics than his predecessors had. With the defeat of the Duchy of Athens and Principality of Achaea the last vestiges of the Latin Empire had at last been driven from Greece. Yet the humiliation and horror of the 4th Crusade still burned in the hearts of many Romans, and the schismatic republics of Venice and Genoa continued to hold Greek lands around the Aegean Sea. Venice in particular possessed the islands of Krete and Evia, while owning several ports on the Achaean Peninsula.

At the start of the new Emperor’s reign in 1313, the Roman Empire had a standing fleet of 100 warships, capable of standing toe to toe with the fleets of Venice and Genoa, though not both together. Fortunately, the threat of the trade republics allying with one another against Constantinople was small, as the two had an intense rivalry with one another, both seeking to become the dominant trading power in the Mediterranean Sea at the others expense. Emperor Ioannes IV had been able to exploit this rivalry to his advantage in the past, and his son would continue to do so during his reign.

The Empire’s chief adversary however remained the Turks in the east, in particular the Turks following the charismatic, skilled and very aggressive Osman Ghazi. Since his rise to power in the early 1280s, he had relentlessly launched raids and incursions into Roman Anatolia, seeking to conquer the rich territory for his own clan. Though his attacks had always been repelled, often at a very high cost, he would always return within a few years time with an army even larger than the last. Border forts on the Anatolian frontier would always be restrengthened after each attack, but the sheer ferocity of Osman and his fanatical Muslim clansmen would always pose a grave threat to the survival of the Empire.

Despite his lack of permanent success in Roman Anatolia, Osman had proven himself to be an extremely capable warrior in the lands of the former Seljuk Sultanate. Between 1282 and 1313, he had conquered an empire that was second only to the Emirate of the Karamanogullari, who were their greatest Turkish rivals for the former Seljuk lands. The Roman Empire had relatively good relations with the Karamanogullari, who were seen as far more reasonable than Osman and his fanatical Ghazi raiders. The Empire had supported the emirate numerous times in their attempts to destroy Osman’s growing realm, though these efforts were sadly in vain.

Added to this all to frequent threat from the east was the increasingly powerful Serbia, which had begun making raids into Imperial Macedonia in the 1290s. Though failing to gain significant ground, the Emperor was only able to put an end to the attacks by having his son Manouel Laskaris, the current Emperor, marry the daughter of Serbian King Stefan Uros II Milutin, Anna Neda. This union led to peaceful relations between the Empire and Serbia for the next several decades, but the threat of a renewed Serbian attack on Greece continued to loom over the Empire.

Relations with Bulgaria had remained tense since they attempted to side with Charles I, King of Sicily, against the Empire in 1281, hoping to gain control of much of Thrace and western Greece out of the alliance. Their ambitions were thwarted however when Ioannes IV incited the Vespers uprising in Sicily and forced Charles to abandon his plans for a Crusade. Though it had clear designs on Imperial territory in Thrace and parts of Greece, raids by the Serbs and the Mongols throughout the 1280s and 90s had devastated their land and left them unable to mount any serious incursion into the Empire. By the beginning of Manouel’s reign however the Bulgarians had begun to recover from the misfortunes of the late 13th century, and the Emperor feared that an attack by Tsar Teodor Svetoslav was imminent.

Though the Bulgarian Tsar certainly desired to conquer Roman Thrace for his own realm, his Kingdom had only begun to regain some semblance of prosperity after decades of Mongol dominance and Serbian aggression, and Teodor knew that he would need to bide his time and wait until Thrace was once again vulnerable. Ioannes IV had built several strong fortresses on the northern frontier with Bulgaria in order to protect Thrace, and by extension Constantinople, from attack. These defenses by themselves were only a sufficient deterrent when the Empire was at peace on all other fronts, however.

To dissuade any potential attacks from its enemies the Empire always maintained a sort of stable of pretenders to the thrones of Bulgaria and Serbia. Should one become too menacing, these pretenders would be released back into their homeland with Roman support, where they would wreak havoc and weaken the enemy to the point where they could be defeated militarily, or in the best of cases, be forced to abandon their plans for attack entirely. This generally worked well for keeping its northern borders secure, but was ineffective against the Turks under Osman, as he had no true rival claimants.

Emperor Manouel II was known to be a great lover of the sciences of astronomy and medicine, and greatly encouraged the development of both during his reign. One of his most prized courtiers was Joannes Zacharias Actuarius, a doctor of great skill who served as the Chief Physician in the Imperial Court. Well known for his treatise on urine and widely considered to be amongst the greatest medical practitioners in Roman history, the procedures and techniques outlined in his Περί Ουρων (Peri Oyron) are considered standard medical doctrine for many Roman physicians today.

Close trade with Trebizond lead to a flourishing of astronomy, as the academy founded in the domains of the Komnenos was considered to posses the greatest astronomers in the Hellenic world. A great number of scientific exchanges would take place between the University of Constantinople and Academy of Trebizond during the reign of Manouel II, leading to many new discoveries in not only the field of astronomy, but also medicine, mathematics, grammar and philosophy. The center of learning in the Mediterranean was the University of Constantinople. Wrested from Church control in 1286 by Emperor Ioannes IV, the University quickly reestablished itself as the finest school in all of Europe, where the science and philosophies of great men such as Aristotle, Plato and Archimedes were studied and examined.

More recent philosophers such as Michael Psellos also became prominent in the curriculum of the University. His ideas on mathematics as a way of interpreting the world gained increasing popularity in this period. The works of both Muslim and even Latin philosophers and scientists, such as Ibn al-Haytham and Roger Bacon were also widely taught within the walls of the University. All of this combined to created a great flowering of scientific learning, which brought great prestige and glory to Constantinople and the Empire in general. Even many would-be scholars from Western Europe sought admission to the University to learn from its many gifted teachers and the well of knowledge it had to offer.

This flourishing of Roman science and culture was thanks mainly to the capable, efficient and stable rule of Ioannes IV and his successors. Through political reforms, good administration and military victories, they gradually healed the Empire’s damaged land, keeping it safe from raiders from both the east and west, thus allowing for its people to recover and eventually prosper. Though the Laskarid Dynasty was extremely unpopular with the nobility, who had to endure heavy taxation and often the direct confiscation of their property, they were immensely popular with the lower and middle classes.

While Emperor Ioannes IV had heavily taxed the immense wealth of the Dynatoi in order to reconstruct the Roman navy and fund the reconstruction of Constantinople and the rest of Greece, both of which had suffered greatly under the rule of the Latins, he had been quite moderate in his taxation of the lower and middle classes, allowing them to rebuild and recover their damaged land following its liberation. Emperor Manouel II continued with many of the same policies that had become common since the reign of Theodoros II, including the appointment of bureaucrats from the middle classes, often at the expense of the Dynatoi, who had traditionally dominated the politics of the Empire.

The army and the church continued to support Manouel II as they had his father, and this secured his position as Emperor. Nevertheless, he would face numerous assassination attempts during reign, most of them arranged by resentful nobles who despised the Emperor and his perceived hostility to the Old Families. These attempts would all fail, often to the painful regret of their benefactors. While his economic policies proved popular, his religious exploits proved to be considerably more controversial. His often too close relations to the Pontiff in the Rome caused many to fear that he would attempt to reunify the two Churches, which had been separate for over 250 years.

The main fear that stood in the way of any potential reunification was the idea that the “Roman” Catholic Church sought not true unification, but rather the conversion of the Orthodox Church. They feared that Rome would force them to abandon all of the traditions they held dear and adapt those of the west. There was also the bitter resentment that still lingered in the population following the 4th Crusade, which did much to prevent any sort of peaceful unification of the two distinct branches of Christendom.

Though his warm relations with the Papacy always kept the Ecumenical Patriarch on edge, Emperor Manouel II never actively sought the unity of the two Churches, likely fearing the reaction of the Orthodox Church as well as his people, both of whom he depended on to retain the throne. In terms of his actual religious practices he was quite devout, routinely praying for guidance in the Hagia Sophia each morning. He also personally baptized his son Theodoros under the watch of the Patriarch.

For the first few years of Manouel II’s reign, he focused on improving the Empire’s relations with its neighbors to the west, Bulgaria and Serbia. He had already married the daughter of the Serbian King, Anna Neda in 1297 and bore a child with her. Wishing to avoid any future conflict with Serbia, the Emperor had his young son relinquish any claim on the Serbian throne he possessed, as a sign of his good will towards the kingdom. Bulgaria proved more difficult, as the two ruling dynasties had had cold relations since the War of the Sicilian Vespers.

In order to deter a potential Bulgarian attack, Manouel II reaffirmed and strengthened his alliance with the Kipchak Khanate by marrying off his eldest daughter, Aelia Laskaris, to Uzbeg Khan. From the Khan he gained a promise of assistance should Bulgaria begin making aggressive moves against the Empire, a promise which served to frighten the Bulgarian King, Teodor Svetoslav, out of any plans for an invasion of the Empire. This, for the next few decades at least, secured the Empire’s northern border.

The first years of Manouel II’s reign were mostly peaceful aside from the occasional Ghazi raiders in Anatolia. From an early age the Emperor’s father had raised him with a strict but fair hand, having him study and learn the skills necessary to succeed him as the Autokrator of the Romans, allowing time for the young Manouel to enjoy the pleasures of life only after he had sufficiently completed his assigned duties, instilling strong sense of responsibility in him. This stern but evenhanded upbringing had forged him into a competent ruler, and he in tern strived to raise his own son, Theodoros, with the same discipline and dedication.

In order to give his son the experience he needed to effectively rule the Empire, Manouel II had him crowned Co-Emperor as Theodoros III in 1316, on his 18th birthday. One of the first acts by the young Co-Emperor was the construction of the Sangarian Wall in 1317. The Sangarian Wall, named for the river Sangarius it paralleled, was intended by Theodoros III to serve as a last line of defense in Anatolia, with the intention of cutting off access to both the Dardanellia and Boshporus straits in order to prevent a hostile army from attempting to cross over into Thrace.

The construction of the walls lasted until 1321, and cost over 60,000 gold pieces, but would prove worth the high cost in the decades to come. Emperor Manouel II continued his father’s policy of a strong defense in Anatolia while slowly strengthening the Empire’s position in Greece. After the fall of the Latin states of Athens and Achaea, the only independent Greek state that remained was the struggling Despotate of Epiros, which had obstinately fought against Roman rule even after the fall of its capital of Arta to Ioannes IV. It was only the increasing threat of the Ottoman Turks in the east that prevented the Empire from simply finishing the decrepit remnants of the state off.

In 1326 Osman I Ghazi died, leaving rulership of his growing Baydom in the hands of Orhan I. Now called the Osmanli Tribe after their founder, their lands in Turkish Anatolia had began to rival those of the Karamanli, a Roman ally. Though successful military victories against the incursions of Osman had prevented them from expanding in western Anatolia, they had met only with success in the east. This successful expansion had once again made the Osmanli Tribe feel confident enough to attack the land of the Romans, and in 1328 Orhan I lead an army of 35,000 men, assembled from his own realm as well as those of his allies, towards the Roman city of Kotiaion. Under the leadership of Emperor Manouel II the Turkish army was defeated by a Roman force of 30,000 men, a victory that nearly saw the capture of Bay Orhan himself.

Nevertheless, casualties were high on both sides, as was common when the two powers fought, and Manouel II was unable to follow up on his victory. The Osmanli defeat at Kotiaion did weaken the Turks enough to foil Orhan’s western ambitions for the time being however, and allowed Emperor Manouel II to turn his attention back to Greece. In 1333, a Roman army of 8,000 marched into the remaining lands of the Despotate of Epiros with the intent to annex the rightfully Roman lands back into the Empire from whence they came. Opposed by a mere 2,500 men under Despot Ioannes Komnenos Doukas, they easily routed the meager army, while the former Despot fled into Serbia.

With the final destruction of Epiros, absolute Roman rule in Greece had been reestablished. While the crippled Despotate had hardly posed a threat on its own, it was nevertheless an enemy that could potentially cause problems for the Empire when it was distracted by other, more serious foes. With the annexation of Epirus, the only remaining independent Greek state outside of direct Roman control was the Empire of Trebezond, and it was to the Far East, separated by a sea of Turks and posing no threat to Imperial legitimacy.

With the prosperity of both the Empire’s lands in both Greece and Anatolia, the Dynatoi were able to recover some of their lost wealth, as the taxation of their estates was gradually lessened. The middle and lower classes, considered wealthy when compared to their western counterparts, supplied the Imperial treasury with a steady income, while taxation was always kept at a tolerable level during the reign of Manouel II, so as not to alienate his greatest supporters. His balanced policy of taxation gradually began to cool relations between the throne and the nobility during the later years of his reign, and served to further centralize the Emperors power as opposition to the Autokrator decreased.

The Imperial Navy continued to grow in strength during his reign as well, expanding to 120 military vessels by the time of his death in 1338, larger than the navies of either Venice or Genoa. If not for the fear that they might put their rivalries aside to unite against a greater threat, the Emperor would have surely made moves to reconquer the various islands of the Aegean that remained under Latin occupation, as well as the island of Krete, which had become the central trading port for Venice’s operations in the eastern Mediterranean.

Roman trade on the Mediterranean nevertheless flourished during the Emperors reign, and was further strengthened in 1336 when a naval expedition captured the Black Sea ports of Kaffa and Phanagoria from its Shamanist Mongol rulers, who had declared their opposition to Uzbeg Khan, who had converted to Islam and thus alienated many of his Pagan supporters in the Mongol nobility. Though the occupation of the rightfully Greek port cities strained relations with the Khan, his ongoing war with the Ilkhans in the southeast held his attention, allowing the Empire to retain their new conquests in exchange for free trading rights within the port cities. This gave the Empire almost complete control of the Black Sea trade, much to the chagrin of Genoa who had placed its sights on the lucrative ports.

By 1338, Constantinople had a population of over 165,000, numbers not seen since before the 4th Crusade. The Roman dominated Black Sea trade saw the City experience an astonishing growth over the next decade, containing at least 200,000 people by 1347 as people from across the Empire and even from regions beyond it flocked to its gates to experience and partake in the wealth of Constantine’s City. Much of the ever-growing Imperial treasury went towards rebuilding parts of the old City to accommodate the rapidly growing population.

It is said, though not confirmed, that in his last years the Emperor did attempt to arrange a unification of the Churches with the Latin Pontiff on more or less equal terms, but this evidently was unsuccessful if it is indeed true, as he passed away on July 17th 1338 with the two Churches still separate. It would however explain his son Theodoros III’s attempts at unification during his reign, given his close tutelage under his father. Regardless, following the death of Emperor Manouel II, Theodoros III became sole Emperor.

A pious and capable Emperor who continued the successful policies of his father Ioannes IV, while passing them on to his own heir Theodoros III, he saw the further growth of the Empire as a Mediterranean power. Under his reign the Turks attempts to drive the Romans from their rightful lands in Anatolia continued to be foiled, while science, art and culture flourished in equal measures. By the end of his reign the Empire was feared and respected on both land and sea, and was the strongest of the three competing naval powers in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Empire’s newfound prosperity and indeed its very existence would soon be threatened by the approach of a dangerous new enemy, however. An enemy not of the sword, spear or arrow, but of the sky, of the vermin, lurking unseen until the cold hand of death was already securely around its victim’s throat…

Georgios Frantzis let out a low sigh, glancing outside at the dark sky. He had not yet completed this volume of his tome, but he had made good progress. He did not look forward to recounting the tragedy that followed, the gruesome death and destruction that gripped his beloved Empire those many years ago. But he was a historian, and it was his duty to provide future generations with knowledge of both the good fortunes that God has blessed the Empire with, and the tragedies that had often times befallen it.

Leaning back in his chair and gently rubbing his tired eyes, Georgios placed his quill back into its stand, but tonight left his incomplete tome open. He still had time, and it was time he was determined not to waste.

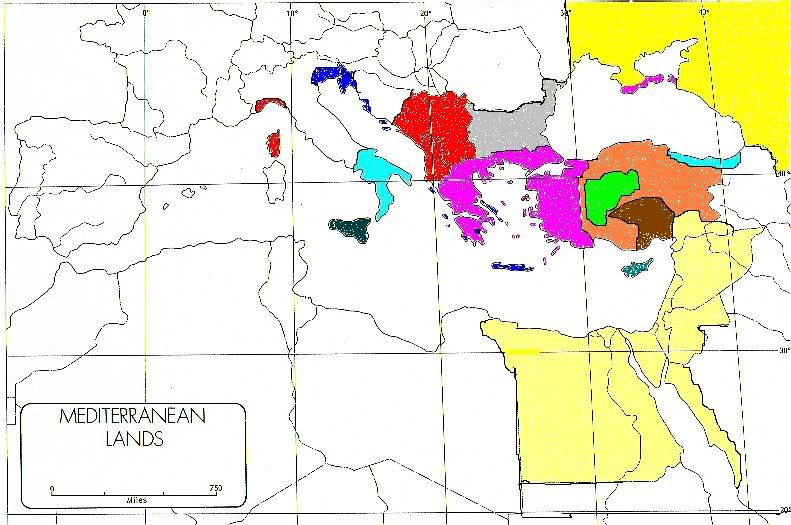

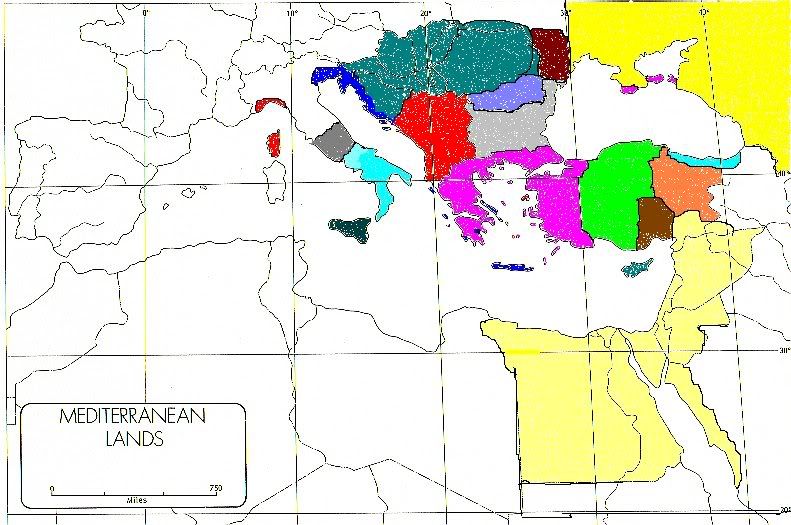

The Roman Empire at the beginning of the reign of Theodoros III Laskaris. Ottoman Empire is light green, Venice is deep blue, Genoa is red, and Karaman is brown. The rest should be obvious. Serbia is also red, but has no relation to Genoa...

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There you go! Hope you enjoyed it.