The Age of Brass: A Spanish AAR

- Thread starter RossN

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 31 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twenty Two: The Second Carlist War and the Election of 1876 Chapter Twenty Three: Foreign Affairs Chapter Twenty Four: 'Alfonsismo' Chapter Twenty Five: The Crisis of the 1880s Chapter Twenty Six: The Fourth Carlist War Chapter Twenty Seven: Post-War Spain Chapter Twenty Eight: A Throne Falls... Chapter Twenty Nine: Revolution and RecoveryViden: Great to have you along and thanks for the notes.I'm afraid I know little about Spanish history during this period, save from Wikipedia, but I'll try not to make huge mistakes!

I am sure you know more about Spanish history than the average Spaniard of any hemisphere.

Interesting developments. Seeing renewed imperialism in the Americas perhaps you'll go for Haiti? I may be totally wrong, but I remember something about France selling their rights of Haiti to Spain. Would be fun if you decided to enforce that sale all out of sudden.

Interesting developments. Seeing renewed imperialism in the Americas perhaps you'll go for Haiti? I may be totally wrong, but I remember something about France selling their rights of Haiti to Spain. Would be fun if you decided to enforce that sale all out of sudden.

Is there anything you'd want in Haiti?

Is there anything you'd want in Central America?Is there anything you'd want in Haiti?

Is there anything you'd want in Haiti?

Glorious conquest?

Chapter Eight: El Salvador

_(14597756640).jpg)

Spanish and Mexican soldiers clash at Puerto Lempira, April 1853.

Chapter Eight: El Salvador

The re-conquest of Honduras had left Spain with a permanent presence in the mainland of the Americas. Even with the end of Don Baldomero Espartero's fanciful dreams of a Mexican Empire in perpetual union with the Spanish Crown, the spectre of painting Central America gold on the map retained its allure in Madrid. Obviously the war in Europe had prevented such ambitions from being realised, but before the negotiations at Breslau had even come to a close the government was drawing up plans for an invasion of El Salvador.

The principle architect of renewed intervention in Central America was the Duque de la Victoria. Espartero remained as President of the Council until December 1850 to negotiate the peace of Breslau with the other allies. After that and at the request of the Queen he stepped aside from the premiership which was retaken by Luis González Bravo. Espartero retained the war ministry and the enormous influence the war had restored to him. The seemingly pointless carnage in Europe and the frightening events in Paris had convinced Espartero that Spain was best served rebuilding her colonial empire through a mixture of cautious warfare and economic and diplomatic pressure. With the United States and the British preoccupied with each other it was hard to imagine a better time to expand in Central America.

Though Espartero was undoubtedly the visionary of restoring Spanish authority in the region the general mood was with him. The restoration of Spanish fortunes seemed so clearly tied to recovering the lost provinces. Reasons of prestige, common blood and culture and economics all made Espartero's proposals attractive even for a war weary people.

El Salvador immediately bordered the now Spanish owned Honduras and though smaller in size was more densely populated. The capital city of San Salvador was the second largest city in Central America (after Guatemala) and though landlocked gave access to the fine deepwater port of Acajutla on the Pacific Coast [1]. The young republic was primarily a coffee exporter though the beginnings of a clothing industry had sprung up in the capital. In the early 1850s El Salvador was a conservative democracy, the presidency and general politics in the hands of a class of rural oligarchs.

In military terms El Salvador was a dwarf with a small standing army. Her navy was surprisingly potent for El Salvador's size but being based on the Pacific Coast would have limited use against an invasion from Spanish Honduras. More concerning was the El Salvadorian alliance with neighbouring Nicaragua and with the more distant but much stronger Mexico. However even this was not so great a deterrent to Spanish ambitions. Nicaragua had a smaller army than her neighbour. As for the possibility of Mexican intervention the attitude in Madrid was sanguine.

El Salvador & Spanish Honduras, February 1852.

Mexico had suffered through a truly miserable decade. The loss of Texas, the rise and fall of the monarchy, the civil war and then the defeat by the United States had left the nation reeling. Few foreign observers believed that the Mexicans would be able to act on the global stage for many years; most believed that the future of the former New Spain would be one haunted by coups and internecine warfare. Even Espartero, one of the few in Spain who retained an abiding interest in Mexico felt that she was essentially finished as an independent power. Unfortunately for the Spanish one man would prove that view wrong. After the end of the Mexican-American war Santa Anna returned to his native land. Though his actual position would fluctuate throughout the decade, sometimes holding the presidency, sometimes merely commanding the army for most of the 1850s Santa Anna was the true ruler of Mexico.

Santa Anna resisted the temptation to begin a war of revenge against the United States. The shrewd general and politician saw that even should the United States lose her conflict with Britain she would still be far stronger than Mexico. Rather Mexican interests were best served building her own empire (in the non-monarchical sense) in Central America. His reasoning was strikingly similar to that employed by Espartero, albeit laced with the self serving rhetoric of opposing Spanish imperialism.

As much as the war of 1852 to 1854 was anything it can be understood as a clash of will between the Mexico's Napoleon and Spain's Caesar.

On 22 February Spain declared war on El Salvador. Initially the campaign went as well as might have been hoped. Most of the twelve thousand soldiers available to General Carlos Fernández had seen long service in Honduras. Some, especially in the officer corps were veterans of the Honduran war and knew the conditions of the Central American peninsula well. A regiment of local artillery raised in recent years from loyalist families complemented Fernández's superior numbers with superior guns.

General Fernández defeated the El Salvadorians in the field on 5 March and began a siege of the enemy capital, diverting some of his forces towards San Miguel. San Salvador was a well defended city and even with his artillery Fernández expected the war would last until at least October. It promised to be a miserable experience for the Spanish forces, facing a perpetually hot climate and for the beginning of May the promise of daily thunderstorms. The possibility of earthquakes added another element of misfortune to both sides though mercifully no major tremors would strike that year.

Mexico had declared war on Spain as soon as the invasion began and the Havana based naval squadron was ordered to patrol the Gulf Coast. The Spanish fleet consisted of the elderly Censeur (74-guns) and three sail frigates [2]. Once it became apparent that the Mexican fleet was more formidable than expected reinforcements would be sent from Cadiz but though the warships of both sides plundered merchant shipping with abandon and the Spanish bombarded Vera Cruz a great naval clash never transpired (though the Spanish would fight the Nicaraguan fleet when the latter made a daring raid on the Balearics in 1854.) The Spanish-El Salvadorian War would soon pass in nostalgic nautical mythology as the last conflict involving a Great Power where all participants replied on sail power alone for their navies but this isn't entirely true. Though the backbone of the Armada Española remained the ships of the line three steam frigates had entered service very recently [3]. Outnumbered by their sail powered sisters and outshone in the public mind by the stately men o' war the three vessels performed efficently but their star turn would have to wait for a later war.

The Spanish naval blockade in the Gulf of Mexico.

In so much as Mexican opposition had been expected at all Madrid had supposed it would come at sea. What had not been foreseen was that Santa Anna would bully the government of neutral Guatemala into allowing the passage of Mexican troops. In late July 1852 while Fernández was still besieging San Salvador a twenty thousand strong Mexican army under Martín Guerrero crossed into Spanish Honduras at San Pedro Sula. Though the outnumbered Spanish forces managed to defeat Don Martín twice in November the torrent of fresh Mexican troops continued to flow across the border and Fernández was defeated decisively at San Salvador on 18 December. Retreating to San Miguel he was surrounded and forced to surrender on 27 December.

The collapse of the Spanish Army in Central America left the whole of Honduras open to a counter-invasion by the Mexicans and the Nicaraguans. In the first third of 1853 most of Honduras would be overrun, including the capital of Comayagua.

News of Fernández's surrender severely weakened Espartero. The Duque de la Victoria's great personal prestige with the public and the Army allowed him to cling on to the war ministry but his hold over the government was broken. In a sign of the times the Queen simply overruled his choice for the Central American command (Benito Assenio) with her growing favourite and Espartero's nemesis, Don Carlos Ortega, the Marqués de Vigo.

In fact both generals would serve with distinction. Assenio arrived with fifteen thousand men in April and managed to break the Mexican/Nicaraguan march on Puerto Lempira. With that victory Spain retained a foothold on the mainland and a viable port but it was not till General Ortega arrived after in August 1853 with another fifteen thousand troops that the war began to swing back towards Madrid. The slow, painful process of first recovering Honduras and then pushing back into El Salvador was complicated by a local rebellion.

Broadly speaking the Hondurans had at least acquiesced to Spanish control after the war of 1843 to 1845. Those old enough to recall the old authority of Madrid or from families with traditions of royalism welcomed the return of Spain, as did some who had experienced only disruption and dictatorship during the intervening years. The majority were prepared to keep their head down. Tomás Barrios and Jesús de Cárdenas were not willing to behave so meekly. In August 1853 the two hotheaded patriots launched rebellions in La Cebia and San Pedro Sula aimed at restoring an independent Honduras.

The Honduran Rebellion of 1853 revealed how complicated the war was becoming as Barrios and Cárdenas were willing to turn their muskets on both Spanish and Mexican garrisons. Mexico, for all her grandiose rhetoric of freedom from European tyranny was (in the eyes of Honduran nationalists) every bit as imperialistic as Spain. In the end they probably caused more damage to the Mexicans, as more than one siege of Mexican forces would be 'inherited' by General Ortega after driving off the rebels. The last of the Honuran rebel forces were defeated at San Pedro Sula in the dying days of 1853.

The war in December 1853; Assenio has defeated a Mexican/Nicaraguan force at Puerto Lempira while Ortega has liberated La Cebia.

Back in Spain there was a growing desire to end the war as quickly as possible. The outside world had not remained idle. In August 1853 the United States had been forced to sign a peace treaty with the British handing over the slice of the Oregon Territory north of the River Columbia [4]. This defeat had humiliated the Americans and had lead to the landslide victory of the Whig Millard Fillmore in the 1852 presidential election ending two decades of Democrat dominance. The Americans had reasonable relations with Spain but with their defeat in the North it seemed likely they would seek to throw their weight around in Central America. Luis González Bravo even informed the Queen that should the United States push to broker a 'fair peace' it would difficult for Spain to refuse.

On 5 October 1854 San Salvador finally surrendered. The government had fled to San Miguel, which held until 21 December. On that morning, having finally abandoned hope of reinforcement from Mexico or Nicaragua they surrendered to Ortega. Technically speaking the war did not end then as Spain would remain legally in conflict with Mexico for several more weeks until a peace treaty was signed but there was no additional fighting.

Though a success the El Salvadorian War had been a far harder conflict than Spain had anticipated. The Army had expected and prepared well for the hard conditions of fighting in Central America and on a purely technical level the troops had done well. The use of mountain artillery, modern muzzle loading rifles and quinine all met with success and had the war happened a decade earlier casualties might have been double those actually suffered. The problem was that the Government in Spain had gone into the fight believing it would be over quickly, that Mexico lacked both the ability and the determination to intervene in any significant way. Almost three years of bloody fighting and several humiliating defeats had proven just how flawed that idea was.

In the future, if Spain was interested in restoring more of her lost American territory she would have to fight planning for a large war, one that required men and guns from Europe rather than small colonial forces at hand. It had been a sound strategy to wait until the United States had been occupied but after facing Mexican grapeshot and bayonets Madrid would have to be careful about her other rivals in the region.

Spanish possessions in the Americas as of the end of 1854.

Footnotes:

[1] In games terms the province of 'San Salvador' has a a port which I am presuming to be Acajutla.

[2] While I did get to battle the Nicaraguans I'm disappointed I missed battling the surprisingly impressive Mexican navy - it would have made an impressive battle for the fading days of the Age of Sail.

[3] The Alcalá Galiano, the Almirante Antequera and the Almirante Ferrándiz.

[4] Ie. The modern state of Washington.

J_Master: Not very likely I'm afraid. Apart from the power disparity the Carlists complicate matters a lot.

Surt: Sound strategy. It might be a while before any more conquests though - my war justification was discovered almost straight away so I'll have to burn off infamy for a few years.

Riotkiller: As of August 1853 (directly after the British and Americans signed their peace treaty) Spain has the fifth largest navy afloat with 30 vessels. Ahead of me are Austria (!) (35 ships), the Netherlands (39 ships), the Americans (46 ships) and the British (87 ships.) Directly behind me are the French (27 ships) and the Ottomans (26 ships.)

Proper Naval update soon!

stnylan: Absolutely. As I said before I'm genuinely disappointed Napoleon III didn't happen; I would have been very interested in what happened there.

guillec87: That hasn't happened yet but it might...

Southernpride: Boo, hiss!

Viden: Heh, thanks.

ThaHoward & Telcharinogrod: Huh. Haiti hadn't occurred to me before but that is an intriguing idea.

Surt: Sound strategy. It might be a while before any more conquests though - my war justification was discovered almost straight away so I'll have to burn off infamy for a few years.

Riotkiller: As of August 1853 (directly after the British and Americans signed their peace treaty) Spain has the fifth largest navy afloat with 30 vessels. Ahead of me are Austria (!) (35 ships), the Netherlands (39 ships), the Americans (46 ships) and the British (87 ships.) Directly behind me are the French (27 ships) and the Ottomans (26 ships.)

Proper Naval update soon!

stnylan: Absolutely. As I said before I'm genuinely disappointed Napoleon III didn't happen; I would have been very interested in what happened there.

guillec87: That hasn't happened yet but it might...

Southernpride: Boo, hiss!

Viden: Heh, thanks.

ThaHoward & Telcharinogrod: Huh. Haiti hadn't occurred to me before but that is an intriguing idea.

Spanish Navy stronger than the French? That's definitely not a bad spot.

Tough war but a good result

Tough war but a good result

A titanic clash between Old and New Spain for dominance over Central America. Old Spain has won this round, but "New Spain" has shown that it can draw blood, and even potentially cripple those who take it lightly. Something tells me that, even if Spain and Mexico never directly clash on the field again, this is merely the first round of many.

maybe you should go for Haiti and some African minor... I believe only central America could be restored... South America not see how

A very well written up war, in very many respects an absolutely classic @RossN post.

I have to say I did smile when Britain one that war.

I have to say I did smile when Britain one that war.

maybe you should go for Haiti and some African minor... I believe only central America could be restored... South America not see how

By rephrasing it as "infamy suggestion", not "infamy limit"

In the name of the King!

The 2nd Reconquista must continue!

Vile Carlist traitor Spain has a Queen named Isabella ii

Last edited:

Vile traitor Carlist Spain has a Queen named Isabella ii

Hmmm... I think you mixed both sides.

Normally it's Carlist Spain that does the whole Second ReconquistaHmmm... I think you mixed both sides.

A very interesting story. You write good characters and convey the difficulties and frustrations of trying to drag a decaying power back to relevance and glory. I am looking forward to more updates, especially to see how the Spain-Mexico rivalry develops in Central America.

Chapter Nine: Isabella and her Ministers

Madrid circa 1850.

Chapter Nine: Isabella and her Ministers

Even her many critics would have to admit Queen Isabella II of Spain was an improvement on her father. Whatever the troubles of her early reign the Spain had not been invaded by a foreign power or shaken to pieces by wars of independence or even gone bankrupt.

The Queen's flaws and weaknesses were very real but in her defence it may be said none of them were rare among the monarchs of Europe and had she been male it is likely she would not have been slandered so viciously. The Spanish monarch was a fickle sybarite, indulging herself in a parade of handsome favourites. Like her sister queen Victoria of England, Isabella celebrated the private pleasures of the boudoir; unlike the fortunate Empress of India Isabella's marriage was loveless. Francis was a notoriously poor match for the robust and fun loving Isabella. The King was slight and strikingly effeminate, depending on which court gossip one listened too was either impotent or willing but uninterested in women. Rumours swirled over the true parentage of 'their' children.

Had the Queen simply been a mindless libertine her reputation among some in Spain (and overseas) would have remained poor yet essentially uncontroversial, but Isabella actually took a strong interest in politics. Per the 1837 constitution the Spanish monarch had defined limits to his or her powers and it was understood that true national control had shifted to the Cortes. This did not render Isabella a mere figurehead - even a parsimonious reading of the constitution allowed the monarch strong vetos among other prerogatives - but it left a willful Queen liable to butt heads with her governments. The Queen interfered and both her stubbornness and her haughtiness grew as she reached her late twenties. The travails of the El Salvadorian war had robbed the Duque de la Victoria of his aura of power and in December 1854 he departed politics, seemingly for good. Relations between the monarch and Don Baldomero Espartero had never been fine and she took his departure from the scene with undisguised glee.

Despite her own preferences in personal pleasures the monarch was partial towards the conservative and clerical factions of the Moderates over the liberal and secular Progressives. In itself this was unproblematic as the Moderates enjoyed such crushing success at the elections of 1850 and 1854 that it had sometimes seemed the Duque de la Victoria carried all Spanish liberalism on his back. However the Queen's opinions were not restricted to factions but carried over to individuals and policies.

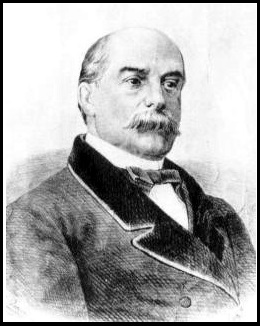

The most loyal servant of the Crown in the Cortes and, after the now twice fallen Duque de la Victoria the dominant politician in Spain was Luis González Bravo. Several times in the decade after the El Salvadorian War the philanthropist and journalist would hold the presidency and it was a rare year when he was not at least in the Cabinet. With his dapper mustache and penchant for sarcasm (he had founded several newspapers and enjoyed an early career as a playwright) Don Luis was a true and faithful royalist and one of the few who was neither military officer nor clergyman who could gain the Queen's ear. It was on his advice that Spain stood aloof from world events for several years after annexing El Salvador. Don Luis was an experienced diplomat but he and most of his fellow Moderates stressed the need for Spain to avoid foreign entanglements while her economy and military recovered from the two most recent wars.

Don Luis González Bravo.

Even given Isabella's coolness towards the 'Citizen King', Louis-Philippe's fall had shocked her to the core. Since 1830 the French monarchy had served as a ready comparison for Spaniards, an example of a parliament and monarch cooperating. If that system had proven so brittle and fragile then did it mean Isabella's own throne was in danger, and not simply from the Carlists?

A glance at the composition of the Cortes throughout the 1850s suggested little cause for paranoia. If the conservative deputies elected in 1850 and 1854 harboured any republican desires they played their cards close to their chests. The conditions that made politics so bitter in France with a large and passionately engaged middle class simply did not exist in Isabella's Spain, still an overwhelmingly rural country. True, Spain had gradually grown more industrialised with lumber mills in Nueva Castilla, paper mills in Valencia and a clothing industry in San Salvador and the government invested heavily in the railways. However there were no true skilled factory workers comparable to those in New York, London, Paris or Berlin. The Spanish middle classes were little different from those that had existed in the previous century - artisans, bureaucrats, military officers, clergymen [1].

The seemingly innate conservatism of Isabella's Spain rendered overt republicanism unlikely. Yet unlikely was not the same as impossible and Isabella who had spent almost her entire life as a ruling monarch had witnessed how her own mother had been toppled and how even Isabella herself had often been a pawn in the games of ambitious generals and politicians nominally on her side. The Queen played her favourites but the men she could trust where not common. Hence the incalculable value of Bravo, a man capable and loyal.

Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière, second President of the French Republic.

For Don Luis, Republican France remained a power to be coddled even when, or perhaps most because, Spain maintained an isolation from such great events as the Crimean War of 1853 to 1855 that saw Russian ambitions in the east thwarted and a new kingdom of Romania born. France under President Louis-Eugène Cavaignac had been the decisive power in the war, surprising many foreign observers who had assumed the new liberal republican government in Paris to be weary of war. What no one had counted on was that M. Cavaignac, keenly aware that questions abounded about his election had seen the war as an opportunity to unite the quarreling strands of French opinion under his authority. French liberals loathed the autocratic Russian regime, French conservatives were determined to preserve the authority of France in the Holy Places.

Cavaignac himself did not remain in office till the end of the war, his four year term expiring in November 1854. Nevertheless Don Luis had shrewdly supposed General Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière would win the subsequent election and continue Cavaignac's policy of muscular liberalism.

Don Luis did not seek an alliance with France. Not only would such a diplomatic move betray his policy of caution in foreign affairs it was highly unlikely even he could persuade the Queen on such a move. Nor was he blind to the fact that France remained an economic and political rival, especially in Morocco where Spanish delegations tended to be given the run around by the Sultan. Abd al-Rahman ibn Hisham, the canny ruler of Fez was in the French pocket and the indignities of Spanish merchants in Tangier was a daily torn in the side of the Madrid government.Still, France was the strongest power on the continent and had invaded Spain twice in living memory. Good relations were a necessity. On 6 April 1856, after a minor defeat in the Cortes Don Luis stepped aside and asked the Queen to be sent as ambassador to Paris. There he could smooth over relations with the French and keep his political antennae twitching [2].

Bravo departs as Vigodet enters.

The man the Queen asked to form a new government on 10 April 1856 was a sailor. Captain General Casimiro Vigodet y Garnica [3] was an admiral and recently a Minister of the Navy. As a very young man he had the misfortune to fight at the Battle of Trafalgar. Captain General Vigodet was a surprising choice in many ways as the Navy did not traditionally provide many national leaders but he reflected Isabella's mind in three key ways. First and most importanly he was loyal and of no particular personal ambition. Second while Don Leopoldo had many rivals in the Army, Don Casimiro Vigodet was much admired in the Navy. Finally the Spanish Navy was in serious need of reform and the recent annexations in Central America and the war with Britain had reminded the government how vital seapower was.

Unfortunately for Vigodet he scarcely had time to settle into office before events across the Atlantic flared into crisis. On 9 September 1856 Juan Manuel de Rosas, the pro-Spanish caudillo of Buenos Aires and de-facto dictator of Argentina was overthrown. Rosas had never been a beloved ally in Madrid, but he had been prepared to acknowledge the Spanish sphere of influence and Isabella was for war and his restoration at bayonet point. Alarmed, Vigodet managed to talk the monarch away from such a choice, stressing that Spain had already created much unease in both North and South America by annexing Honduras and El Salvador and a declaration of war now would turn the wary into the outright hostile. He further stressed that the Army and Navy would be both be taxed by such a war far beyond the paltry gains that might be seen if Rosas was restored. With ill grace the Queen relented.

The September 1856 rebellion in the Antilles.

A far worse crisis came later that same month with the eruption of revolts in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The Antillian (or Carribbean) Rebellion of 1856 and 1857 was a movement led by and composed of Creole landowners hoping to reform the state of Puerto Rico and Cuba. It was not a true nationalist revolt in the sense of being an independence movement and it was certainly not a slave revolt by any stretch of the imagination [4]. The leader was Gonzalo Rojo, a Puerto Rican-born writer, newspaper editor and diplomat. At his trial in 1858 the Spanish authorities would publish private correspondence from Rojo to several of intimates that revealed the rebel leader and a 'perverse' side but at the time he was seen only as a dangerous demagogue whose austere and lean appearance was at odds with the thunder of rhetoric.

Fortunately for Spain, Rojo was a better speaker than he was a war leader. Though he succeeded in raising an army of twelve thousand men in Puerto Rico (with his disciple Eduardo Varela raising three thousand more in Jagua in Cuba) the rebels had little knowledge in how to actually fight a war. For five months Rojo would terrorise the countryside of Puerto Rico and lay siege to the city of Puerto Rico de San Juan Bautista but he was unable to overrun the loyalist garrisons. At the start of February 1857 the Marqués de Vigo (Carlos Ortega) landed with an army of fifteen thousand and in a bloody battle routed the enemy.

The Battle of Puerto Rico, February 1857.

The revolts in Puerto Rico and Cuba were put down fairly swiftly but that they had happened at all inspired others. In October 1857 Honduran nationalists, drawing from the tactics if not quite the goals of Rojo rose in Comayagua and Puerto Lempira. In total they numbered perhaps twelve thousand men, but split in two groups and outnumbered by the twenty thousand Spanish troops stationed in Central america they were quickly crushed. By late November the last of the rebels had fallen or surrendered. Loyalist casualties were fewer than in Puerto Rico as the Spanish commander General Cristobal Alcalá-Zamora possessed and used with satisfaction two brigades of artillery.

Ultimately the revolts of 1856 and 1857 did not seriously threaten Spanish control anywhere. Even in Puerto Rico, home to the bloodiest fighting the rebels had been quickly defeated. Still, it did suggest that both Luis González Bravo and Casimiro Vigodet had been right to caution their more excitable monarch. Spain was a Great Power, but she was also the least of the Great Powers and had to play her game carefully and cleverly. The Spanish government - any Spanish government - would have to keep in mind how fragile the state was compared to Britain, France or Austria.

Don Casimiro Vigodet.

Footnotes:

[1] I will go into this further in a later update but essentially Spain has no Clerks in a game sense.

[2] In game terms my 'Diplomat' First Minister departed and a 'Lord Admiral' First Minister arrived. As Bravo actually was an ambassador in real life (albeit to London) sending him to Paris seemed the logical move. While not allied with them I have been increasing relations.

[3] A 'Captain General' in this naval context is an admiral. Historically Spain switched to the later usage in the 1860s.

[4] The revolt in Puerto Rico and Cuba was Jacobin rather than Nationalist so it made more sense to see it as a push for liberalism and autonomy than seperatism.

Threadmarks

View all 31 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode