Volume I: The Dusk

Chapter 6: The Barber of Siberia

Room 101

Location Undetermined

Time & Date Undetermined, 1950

- So, from that moment on, did your systematic work on organizing an anti-Soviet uprising in Siberia begin?

- Yes. Moreover, I would note that it is the word "anti-Soviet" that would be most appropriate here. We were well aware that the sympathies of the inhabitants of Soviet Siberia for Monarchism or the White Guard, although being higher than in the rest of Russia, would still be insufficient for a full-fledged armed rebellion. But there were a lot of people who were generally dissatisfied with the Soviet government. You see, Siberia from the first years of its existence as part of Russia turned into a prison colony.

- Like Australia?

- Sort of. The Russian authorities were usually quite humane when it comes to death sentences for political crimes - for the entire nineteenth century, only 625 of them were handed down, and only 191 were executed. Even during the first Russian Revolution, when the Tsarist regime had to be especially tough, only 3741 people were executed in 5 years. Under Stalin, so many people were being killed just in one day. Therefore, usually, if it was necessary to get rid of a person, he was simply sent to Siberia in exile or to hard labor, to live out the rest of his days in an endless snowy wasteland or a remote forest.

- This practice continued under Soviet rule, didn't it?

- That's right. Siberia remained a place of exile for hundreds of thousands of people, and many of them clearly had very sharp claims to the Soviet government. We could definitely use them.

- Why was such a strange name chosen for a subversive operation in Siberia? Eh... "The Siberian Barber"?

- Oh, that. A play on words. "The Barber of Seville". Rossini, Beaumarchais.

- An opera?

- Yes. In Russian it is called "Sevil'skij Tsiryul'nik". Very similar to "The Barber of Siberia" — "Sibirskij Tsiryul'nik". It was as if we were going to cut off, barb Siberia from the rest of the Soviet Union. And don't forget Svechin's love for music. That's why they jokingly called our operation like that. Of course, it wasn't an official name.

"The Barber of Seville". A musical score (for piano) in pre-revolutionary Russian.

Yes, that's how we started to "barb" Siberia according to the plan. Our next primary targets at the end of October were the lands of the so-called "Outer Manchuria", or, in Russian, the Amur and Maritime regions — Priamur'je and Primor'je. One of our cells also originated in the young town of Birobidzhan. It was a slightly crazy project of the Soviet authorities to relocate all Soviet Jews, or at least a significant part of them, to the Far East. The curator of the Birobidzhan project was the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer, one of the most prominent representatives of the "Bauhaus". In 1934, this town, built from scratch, became the center of the Jewish Autonomous Region. Jews were not very willing to leave for the edge of the world in frosty Siberia, but Stalin was terribly proud of this idea, and tried with all his might to increase the Jewish population of this region. Among the Jews, we could not count on a large number of supporters, because they well remembered the times of pogroms, in which Black Hundreds and Cossacks often took an active part, but nevertheless, those offended by the Soviet government were in any community, and therefore the town of Birobidzhan also did not remain without our "attention".

"Star of Birobidzhan" (Birobidshaner Schtern) — the main newspaper of the Jewish Autonomous Region, printed in Russian and Yiddish.

An issue from September 1936 with a photo of Stalin and Kalinin on the front page.

Good news also came from "Inner" part of Manchuria. We managed to establish contacts with the Bureau of Russian Emigrants, the Japanese authorities and the authorities of Manchukuo, including the idea of forming the military forces there. At the end of October-beginning of November 1936, the cautious formation of the first units (primarily Cossack and cavalry) began in order to participate in the upcoming operation. The basis for these troops were the inhabintants of the so-called "Three Rivers" (Tryokhrech'je, Chinese: Sanhe, in Hebei province) district, where there was a significant Russian Cossack population. Some of these Cossacks had already served in the Japanese or Manchurian armies, some returned from the armed formations of the Chinese cliques. They could safely arm and prepare themselves abroad, unlike the preparations of our detachments on the territory of the USSR.

A Cossack boy from

Tryokhrech'je in front of three flags — of Manchukuo, Russia and Japan

In addition, we did not stop working with the "Old Guard" — veterans of the White Movement, who were still quite young and ready to re-enter the battle. Their combat experience, of course, should not be considered absolute — after all, military affairs have changed decisively since the 1920s, but their determination, will to fight Bolshevism and general symbolic significance for the common cause could not be underestimated. Of course, it would be extremely naive to think that it would be possible to put all former White officers and soldiers in Russia and abroad under our banners, but it was certainly worth working in this direction. Pavel and I were able to establish strong contacts with the R.O.V.S., K.I.A.F. and other foreign military associations of the former Tsarist and White armies. Svechin was, very delicately and carefully, but relentlessly establishing contacts among the "Vojenspetsy". The biggest response besides Manchuria was found in Germany and Yugoslavia. The White émigrés there were eager to fight the most, but their upcoming delivery to Russia was a big problem. So far, it was assumed that on the eve of the operation we would be able to transfer them to Manchuria by sea. The "Vnutrennyaja Linija" ("Inner Line"), a White Guard intelligence and terrorist organization, began to provide us with great help. It had been founded by General Kutepov, who was later kidnapped by the Soviet authorities in 1930, and we were thinking that its activities practically came to naught, but now they have resumed with renewed vigor. The new leader of The Inner Line, Klavdij Foss (Claudius Voß), became, in fact, the center of all our intelligence abroad. He was a dangerous and ready-for-anything man, somewhat resembling the sadly familiar Larionov. With him, the work on consolidating the Russian military abroad went much faster.

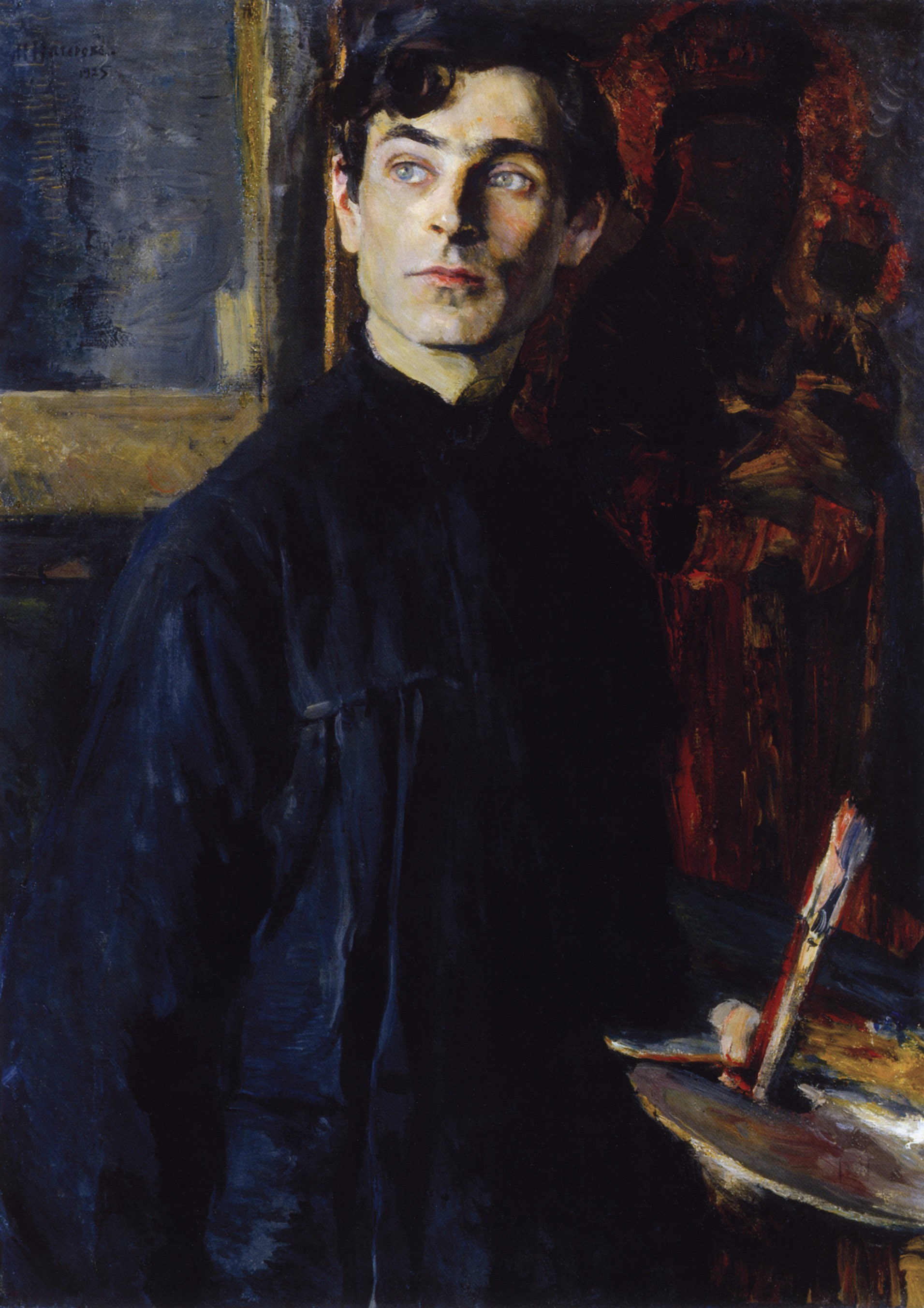

Foss, a Russian officer of German descent, in times of the Civil War. Later he would become the mastermind of the White Emigration's intelligence.

By mid-November, our agents had already started working in Vladivostok — first of all, we were vitally interested in its seaport. We understood that if we didn't take control of him in the first hours or at least days of the operation, everything would go awry. Particularly active work was carried out among the officers of the Pacific Fleet, it was very important for us to capture at least some of the ships, and ideally — all the available naval forces in Vladivostok. The commander of the fleet, Mikhail Viktorov, was regarded by us as a suitable candidate — the son of an officer, a graduate of the Jaroslavl' and Naval Cadet Corps, a veteran of the Battle of Moon Sound. Unfortunately, of course, he was under very strict supervision of the special services with such an "outstanding" biography. We were very afraid that he would be one of the first to fall under the flywheel of repression. The Pacific Fleet of the USSR was weak and small, but due to the deterioration of relations with Japan, it was increasing its power year after year, and in addition, we needed it, of course, not for combat missions, but only for the protection of sea convoys that our "foreign friends" would send us.

Having conditionally begun to "control" the border with Manchuria (that is, having created cells along this border, of course, there was no question of any real control), we began to move further north, towards Nikolajevsk. The Amur region was to become the main rear of our operation, it could be compared with the heart (and the head was Chita). The main, and it seems, practically unsolvable problem remained the rapid transfer of troops and equipment from the Manchurian border to Transbaikalia. Mongolia was a Soviet satellite with troops stationed there, and we could use its territory very limitedly. We could only pray for a possible quick seizure of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which would allow us to carry out this transit in an acceptable time. I contacted the Command with a proposal to move the performance center to Vladivostok or Khabarovsk, but received a categorical refusal — from their point of view, Chita had already increased the necessary potential as the main point of the entire operation, and "changing horses in midstream" was wrong. I had to work with what I had and hope for God.

Nikolajevsk-on-Amur, Soviet Street (

Ulitsa Sovetskaja)

By December we began receiving the information about the first successful recruitment of volunteers already on the territory of the Union. As expected, the Cossacks were the first among the locals to contact us. The Soviet authorities treated them extremely cruelly — even with those who fought in the Red Army (and there were many of them) back, during the Civil War. Before the Revolution, the Cossacks were considered a privileged class, an estate like something between the military and peasants, and they had many benefits from the Tsar and his government. From time immemorial, the Cossacks were considered the basis of the ruling regime, it was on their shoulders that the colonization of the vast expanses of Russia — the Urals, the Steppes, Siberia, and the Far East — lay for centuries. The Cossacks formed the most politically loyal units, which were used to suppress uprisings and riots. All this made the Cossacks terrible enemies in the eyes of the Bolshevik revolutionaries, and when the Civil War ended, the Cossacks were the first of all the inhabitants of the former Russian Empire to feel the full horror of Soviet terror. Many of them fled abroad, but those who remained in the Soviet Union were now becoming more and more interested in the potential overthrow of the current authorities and a return to pre-revolutionary order. First of all, Siberian and Far Eastern Cossack troops, such as the Ussuri, Trans-Baikal, Amur, and so on, fell into the zone of our interests.

A group photo of Trans-Baikal Cossacks of the Life Guards. Note that some of the servicemen are not of Russian, but of native (usually Buryat) descent.

From contacts in Vladivostok, a reasonable proposal was also received to try to form a cell on Sakhalin, since the Japanese would be able to very quickly transfer everything we would need from their southern half of the island. To implement this plan, I contacted Vasilij Oschepkov. He was a man of amazing destiny. He was born on Sakhalin, and after our defeat in the Russian-Japanese War he unexpectedly became a Japanese citizen. He was 13 years old at the time. After that, Oschepkov went to Japan, where he began to intensively engage in judo wrestling. He liked Japanese martial arts so much that he wanted to develop his own combat system — sambo*.

*An acronym from "SAMooborona Bez Oruzhija", meaning "Self-defense without weapons".

In parallel, this outstanding athlete worked very closely with Soviet military intelligence. At the time of the end of 1936, he was no longer trusted, and he was under the close supervision of the security officers, but I was able to convince him that his authority on Sakhalin would be useful for Soviet military intelligence. Thus, I used Oschepkov "in the dark", and he, believing that he was preventing a Japanese provocation, was in fact putting together the basis for our work on Sakhalin. Oschepkov had a very significant trump card — he taught the sambo system to many agents of the NKVD and other Soviet special services, and therefore had loyal and grateful students in the highest offices. This allowed us to pull off the Sakhalin gambit in relative safety for the time being.

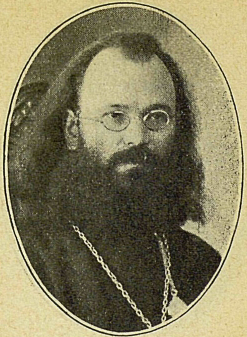

Vasilij Oschepkov, "our man on Sakhalin"

At the very end of the year, a massive repressive campaign in the Air Force began. The Сhekists claimed that the personnel of VVS RKKA (Vojenno-vozdushnyje sily Raboche-Krest'janskoj Krasnoj Armii, Workers and Peasants' Red Army Air Force) was carrying out deliberate and purposeful sabotage, which should be put to an end once and for all. The reason for this was a series of very serious accidents, when we were losing several planes a day. The pilots, some even openly, were saying that the reason for this was not the sabotage of enemies of the people, but technical problems, low production quality, poorly trained flight personnel, where they tried to take not quality, but quantity. However, such conversations did not suit Stalin at all. He believed that the reason for everything was only the atrocities of the counter-revolutionaries. A grand purge was planned in aviation, which pushed a number of Air Force officers to cooperate with us. In addition, military intelligence had a direct task to activate industrial espionage at European, American and Japanese aircraft factories, which indicated that at least some of the authorities still guessed that the causes of accidents were not only in the machinations of enemies.

After carrying out preliminary work in the Far East, we began to "probe" the towns and villages to the north of the Trans-Siberian Railway. It was much easier to work there, because the authorities were practically not interested in what was happening in these regions, and the population there was not enthusiastic about the Communists. My informants in Chita, Irkutsk and Ulan-Ude reported that by the end of the year they would be able to establish contact with part of the settlements in this zone (for example, in Bodajbo), and with a successful combination of circumstances, some of them during the "X hour" could be possibly ocuppied even without a fight, since there are no Soviet troops and even militia (militisija, the Soviet name for police) there may not be. This inspired certain hopes.

Jakutsk seemed like a completely different task. Yakutia was huge and sparsely populated, but its capital was a strategically important city, and it was guarded very carefully. The Soviet government did not trust Yakutia very much and was afraid of it — the Civil War lasted the longest here, the last White leader, General Pepelyajev, surrendered in Yakutia only in 1923 (the war itself ended in 1922, and in most of Russia — even by 1920). Therefore, the creation of our cell there was a very difficult, and at the same time, a necessary step. Another problem was the interaction with Yakuts, the local population. Our command, the heirs of the White Guard, inherited its slogan — "United and Indivisible" (Jedinaja i Nedelimaja, often also "One and Indivisible"), i.e. they categorically opposed any separatism and even autonomy in Russia. The Yakuts were one of the most numerous and well-organized peoples of Siberia, and despite the rather deep Russification (most of Yakuts were Orthodox and had completely Russian names), they had a developed local culture and quite strong national feeling, and already in the Civil War many Yakuts tried to fight for their independence. As a result, it was decided not to play with the Yakut separatist sentiments in any way, and to involve only those natives who were ready to consider themselves part of the common Russian cause in the activities of the organization. Such, however, were also found, and the process gradually progressed. In these labors and worries, the year 1936 finally ended. A year in which I became a completely different person. The year that so abruptly and unconditionally changed my fate. The fateful, mysterious and frightening 1937 was approaching. The dawn of the new year was rising over the land of the Soviets — the dawn of a frighteningly red color.

At the beginning of the year, I went to Harbin under the pretext of conducting reconnaissance activities in the area of the KVZhD**. Artuzov did not object to this, and I was able to see Rodzajevskij for the first time. At that time, I had not yet assumed what role this person would play in subsequent events.

**Сhinese Eastern Railroad (Kitajskaja Vostochnaja zheleznaja doroga). A railroad in Manchuria built by the Russian Empire.

Harbin

Binjiang Province, Empire of Great Manchuria

January 20, 1937

That day I was able to deal with the main official duties earlier than usual. According to the agreement between the USSR and Manchukuo, concluded back in 1935, the railroad was now completely controlled by the Manchus, and a significant part of the Russians who worked for the KVZhD left back to the Soviet Union. However, nothing good was waiting for many at home, and therefore the Russian diaspora in Manchuria was still huge, and Harbin was its true capital. I must admit, I felt very insecure in this city, which seemed to have frozen in time, and if it weren't for the signs with hieroglyphs that came across here and there, I could imagine myself in a provincial city of pre-revolutionary Russia.

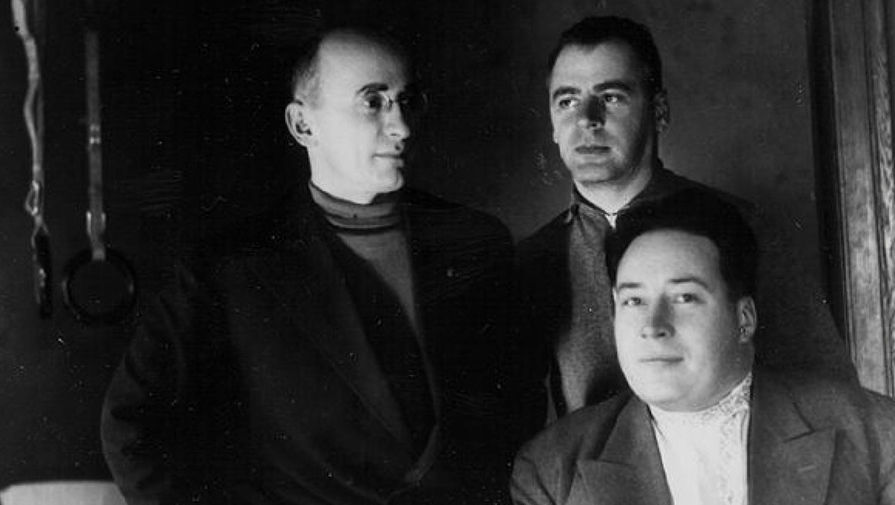

I had a meeting organized by Vladimir Dmitrijevich Kos'min. He was not a brilliant White Guardsman, but, apparently, a brave and honest soldier who enjoyed a certain authority among the Manchurian public. Kos'min was one of the "irreconcilables" — those who believed that even after the end of the Civil War it was necessary to continue the fight against the Bolsheviks. That's why he agreed to cooperate with us. And he promised to set me up with someone with whom I had long wanted to start a close mutual work. With Konstantin Rodzajevskij. I heard that he was a very popular publicist and politician in Harbin, behind whose shoulders the All-Russian Fascist Party (Kos'min was its decorative leader, by the way, but it was Konstantin who held all the real power) has been growing stronger for six previous years. I needed his influence, his men and resources. Specifically, our meeting at that time was devoted to the participation in the upcoming work of their most active and enthusiast paramilitary organization — the Vanguard of Fascist Youth.

We met in a small private restaurant, hidden from outside eyes. Rodzajevskij made a mixed impression on me. He was tall, impetuous, energetic, talkative — it seemed that everything in this man was eager for action. At the same time, I knew something about him. Rodzajevskij was not a White émigré. His conscious life began already under Soviet rule, and he even managed to join the Komsomol*** before he fled to Manchuria in 1925. This made me doubt the ideality and sincerity of this politician, but it made it perfectly clear that he was ambitious, power-hungry and quite unscrupulous. He came to our meeting in the full dress uniform of the Harbin fascists — a black shirt, a swastika armband, high boots shining with varnish. He clearly saw himself as someone like Hitler and Mussolini, only on a smaller scale. I gave him my hand.

***An acronym from KOMmunisticheskij SOjuz MOLodyozhi

(Young Communist League, more literally: Communist Union of the Youth),

main youth organization of the USSR.

- Good afternoon, Konstantin Vladimirovich.

- Hello, Vladimir! — under such a pseudonym I was known among the Emigration, — I have heard a lot about you from Mr. General (he meant Kos'min). I hope your actions at Home are successful. What did you want to discuss with me?

- According to unverified information, I know that the most "capable" men under your — I mean, under your and Mr. Kos'min's — leadership are the Vanguard of the Fascist Youth.

- Oh, yes, these are my best people. Many of them were drilled in the army and police of Manchukuo! Some even trained in Japanese camps! Auxiliaries of the Kwantung Army!

- That's excellent! Tell me, could we expect to use them in about a year in... more "realistic" conditions?

- Hmm, — Rodzajevskij mused, — I understand what you're driving at. In principle, the whole Harbin is full of rumors about this. You know, it's possible. But...

- Yes, Konstantin Vladimirovich? What "but"?

- Oh, come on, you can just call me "Kostya"! I think we are the same age, — the Fascist smiled, — My people are well trained and armed, but there are not very many of them, and each of them means a lot to the movement. We have already made several actions and forays into Soviet territory, we even reached Chita itself and organized propaganda campaigns there. However... In the case of, as you put it, more "real" actions, my people need the most important thing.

- What is it, Kostya? — I asked him in a rather cold tone, nevertheless, switching to a friendly address.

- Some... political guarantees, Vitya... Oh, I mean, excuse me, Volodya! — Rodzajevskij grinned and slapped his forehead, allegedly making a slip of the tongue.

He knew who I was.

- Political guarantees about what?

- You see, my friend, — Rodzajevskij took a sip of beer he had ordered (perhaps imagining himself as someone planning something like a Beer Putsch) and continued significantly, — Of course, we are doing a common cause, but the goals of this cause are quite seriously different for us. The Soviet military, like you, first of all, want to save their skin, and, if possible, to prevent the defeat of the army in the future great war, which will be inevitable if Stalin brings his repressions to an end. Most of your emigrant colleagues still cherish wonderful, but, strictly speaking, absolutely naive dreams about the return of the times and the order of Kolchak and Denikin, or even Tsar Nicholas. We here in Harbin have long understood that the Russian Empire is the past. The Soviet Union is a disgusting present that needs to be ended. But the future...

- So it's you who see yourself as the future?

- Exactly, Volodya, exactly! — Rodzajevskij's eyes lit up, with each new phrase he spoke more obsessively, — Fascism is the future of Russia. This is what unites all the positive aspects of the Empire and the Bolshevik dictatorship, and at the same time is devoid of their monstrous shortcomings. Russia has tried two ways , — both liberal-conservative and socialist. None of them worked. The time of the Third Way is coming! My people will fight for you to the end, but only when you promise that your campaign will allow Russia to embark on a Third Path.

- And you, therefore, see yourself as the leader of this new Russia? — I asked, a little ironically.

- I understand your tone, — Rodzajevskij nodded his head willingly, — No, I'm too young and inexperienced, I don't see myself as the supreme ruler. However, I understand perfectly well that you have nothing to offer the Russian people. They have had enough of monarchy, military dictatorship, socialism... yes, even damn democracy! Do you think the Russian people will be happy that you will return to them something like a Provisional Government? Or maybe some Grand Duke straight from Paris? Ha, the hell with it! The Whites lost in 1922 because they had no ideology. They thought they were military, they were out of politics. It was a monstrous stupidity. I think you don't want to let it happen again. Vladimir, promise me that the All-Russian Fascist Party will get a place in the politics of the future new Russia, and my people, and not only the youth, will do whatever you order them.

- I understand you, Konstantin, — I answered him somewhat dumbfounded, — I will try to discuss this issue with the Command. I think they'll agree.

- Amen to that! — and with these words, he finished his glass of beer.

To say that I was shocked by the trip to Harbin at that time is to say nothing. However, you can probably guess that I accepted Rodzajevskij's offer. I needed every bayonet and every saber, and I had no right to refuse this ambitious demagogue, no matter what he asked of me.

Rodzajevskij and his men on a parade in Harbin

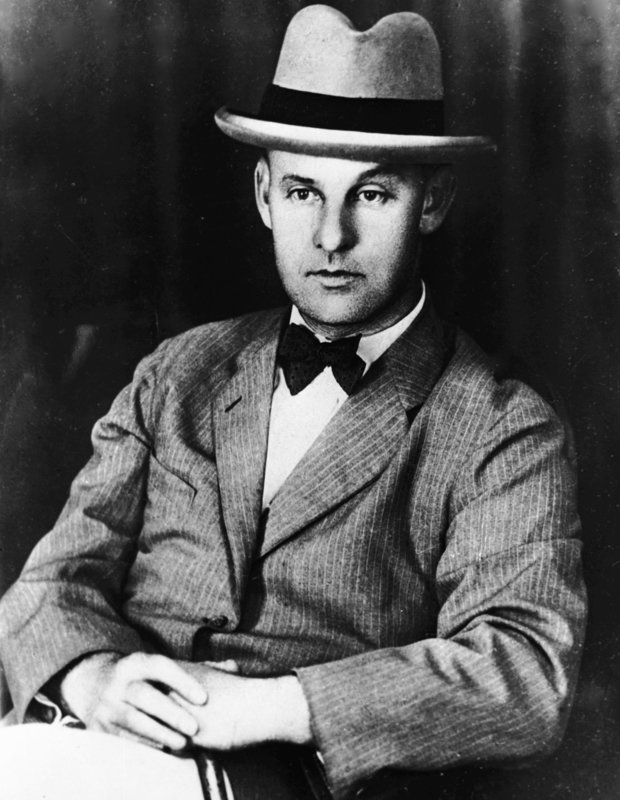

The next victim of the Stalinist regime in the army (and, unfortunately, far from the last) was Dmitrij Danilovich Lelyushenko. We found out about his arrest in the Intelligence Directorate, as if it was completely routine news. No one was particularly surprised by this anymore. He was young, only 36 years old, and it seemed that he had not stained himself in front of the Soviet Motherland — from the very beginning of the Civil War he was a Red partisan, then a soldier of the regular Red Army. One of the pioneers of the tank forces, a graduate of the Frunze Academy (Academy of the General Staff) — nobody would call him an opposition supporter or a counter-revolutionary. Nevertheless, he was linked to another "Trotskyist conspiracy" and shot. Lelyushenko's death, of course, did not leave anyone indifferent in the leadership of the Red Army. Everyone understood — it had begun. Now they could also come for each of the Red commanders, even for people much more deserving and high-ranking. Some of the generals (and, perhaps, most of them), thus, tried with all their might to curry favor and prove their ardent devotion to Comrade Stalin, but some, on the contrary, began to think about whether it was worth continuing to support a regime that could destroy each one of them...

Such frightening signals, of course, forced us to step up our activities. By the end of January, I was informed that work had begun in Krasnojarsk. The "Tuvan strategy" had to be implemented without fail in order to secure our flanks and rear. Our leadership doubted that in the event of an uprising in Soviet Siberia, the authorities of Mongolia and Tuva would immediately come to the aid of the "elder brother" — much more likely, they would sit out and wait for who would eventually emerge victorious from this fight, especially since it would hardly seem from the outside that we have any chances. In this regard, "covering" the Tuvan border was one of our priorities. In addition, of course, Krasnojarsk itself was a very important city, one of the "capitals" of vast Siberia, and we simply could not ignore that place. Day after day and month after month, our "barbing of Siberia" bore fruit and allowed us to branch our network further and denser. Unfortunately, this not only strengthened our future position, but also made the operation more and more risky. At the time of the beginning of 1937, I was already sure that the NKVD or the army counter-intelligence (or, perhaps, both of them together) already suspected something. I had to hurry.

In the Far East, we continued to expand our networks. A small number of our agents have already worked in Okhotsk and in the rest of the North Pacificic territories of the USSR. As mentioned earlier, the principle "the further away from the Trans-Siberian Railway, the safer it is" worked here quite well. However, Okhotsk still remained a part of the maritime border of the USSR, and therefore it was by no means impossible to relax when working in these territories. A great success for us was the recruitment of several key employees of the Port of Okhotsk, some of whom continued their work there since Tsarist times. Of course, the territories in those places were so vast that neither we nor even the Soviet government could actually "control" them in any way — only the hubs and roads between them (where, of course, they existed).

And in February, the second "Moscow Trial" broke out. For the whole country, it was like a bolt from the blue, but of course we in our organization had an idea where everything was going. Stalin again demonstratively and ruthlessly dealt with another portion of the opposition, and this time with those who did not show any real threat to him. It didn't bother him. Since the testimony obtained at the First trial became the basis for the Second, it was called the "Case of the Parallel Anti-Soviet Trotskyist Center" — of course, this was another portion of Stalin's specific sense of humor. Smilga, Radek, Pyatakov, Serebryakov, Preobrazhenskij — all these people who, together with Lenin, made the Revolution, were wiped out in this judgment into dust. "Our" circles continued to gloat, in their opinion it was a retribution and a manifestation of justice to the hated Bolsheviks. Of course, I could not join this point of view, because after the Second Moscow Trial I began to really worry about my father. It was difficult to suspect him of Trotskyist views, rather he joined Bukharin's supporters, and Nikolaj Bukharin was still a loyal ally and associate of Stalin, but accusations against him had already been made at the trial, openly and publicly. Bukharin tried his best to distance himself from the opposition — after the First Moscow trial, he wrote to Voroshilov: "The cynic-killer Kamenev is the most disgusting of people, a human carrion. I am terribly glad that the dogs were shot". But it seems that now the clouds were gathering over Nikolaj Ivanovich personally, and, thus, over my father. We haven't had much contact with him lately, but I felt something needed to be done.

The intensity of repression, inflated by the Second Moscow Trial (which many already understood as the beginning of a new Great Terror), of course, did not avoid the Armed Forces. Here we suffered our first serious blow — during the campaign to eradicate "anti-Soviet military thought" Svechin, one of the key players in our scheme, was arrested. Svechin managed to inform me that he does not yet believe that there are serious reasons for excitement, and most of those undergoing such "purges" are released. However, I didn't know if that was actually the case, or if it was said for general reassurance. In any case, the connection with Svechin was lost, and I had to "reconnect" to all his contacts. It was extremely unsafe to meet with Govorov, since the trials on military academies could affect him as well. Shaposhnikov remained. It was lucky that the army intelligence of the USSR was directly subordinate to the General Staff, and Shaposhnikov was supposed to head it already in the spring. I began to try by hook or by crook to get a transfer to him as an adjutant on intelligence matters. Yes, this weakened the position of our case in matters of external relations, but without access to Shaposhnikov, our whole case was simply doomed to failure, and in connection with the arrest (as I hoped, temporary arrest) of Svechin, there were simply no other ways to influence Boris Mikhajlovich.

But the work was worth continuing, no matter what. The NKVD began to step on our heels and break many of our actions. By the beginning of the spring of the 1937, we realized that now not only Chukotka, but also Kamchatka was lost to us. Actions to stop the Japanese and American threats from the Soviet authorities hurt us badly. Unfortunately, we had to admit that the entire Chukotka-Kamchatkan theater of operations would be in our rear under the control of Stalinist forces, and would obviously cause problems in the future. We could not count on the help of the Japanese in this area, since this would clearly provoke an open war against the USSR. It remained only to rely on some kind of own strength.

There was, however, some good news. We continued to gain a foothold in central and eastern Siberia, and by spring we could count on some moderate support in Tomsk and Kirensk. Tomsk was famous throughout the east of Russia as the student capital, a huge university center in the midst of Siberian snows. There were many professors and students there who were ready to support our cause and had connections all over Siberia. Historically, students are always oppositional and ready to resist any government. During the years of the Russian Empire, the student movement endlessly supplied "fuel" for revolutionary parties. In fact, most of the assassins of Tsar Alexander II were students. Now, during the years of the Stalinist regime, the pendulum bizarrely swung in the opposite direction, and now the students were ready to cooperate with the heirs of pre-revolutionary Russia.

By March, it was possible to sum up certain results, which I had to pass on to the Emigration's leadership. In general, the situation was somewhat optimistic for us, but it seemed that there was definitely not enough time. Stalin's actions, of course, fueled discontent, and thereby indirectly helped us, but we had less and less time to start the performance before the full unfolding of the "Great Terror". In my rather dry report, which I hoped to bring through closed communication channels to Harbin, Paris, Berlin, San Francisco, Belgrade and other "headquarters" of our like-minded people, I gave the following forecast: our movement does not and cannot have broad support among the local population, therefore it should not be seriously counted on. With the boldest estimates, no more than 10% of civilians will support our cause in case of its initial success. At the same time, the situation in the Armed Forces was hopefully way better. The repressions seriously affected the mood of the command staff, and our recruitment work allowed us to make the first serious connections in the ranks of the Red Army. According to my calculations, about a quarter of the officer corps of all branches of the military could support us in the event of a real mutiny. The navy sympathized with us the most — there were the most "Old School" officers there, and it was generally considered the most conservative branch of the armed forces. There wasn't much to brag about, but I've always been a supporter of a sober assessment of the situation, especially in such a risky venture.

The Сommand also understood that we didn't have much time left, and urged us to force the launch of the operation with all our might. I was informed from Harbin that they will be able to prepare an advanced invasion force within six months. This, of course, sounded very optimistic, but we could hardly count on such a tight deadline in the Soviet Union itself. Nevertheless, it was necessary to hurry — Stalin was obviously ahead of us, the "point of no return" was getting closer every day. I was informed that at two conferences held by emigrants in Europe and in the Asia-Pacific region, it was decided that the operation should begin before the end of the year. Very successfully, I received a foreign "service trip" to Berlin (this was my last assignment before transferring to the General Staff), and there I was able to meet with Pavel and discuss the details of what was coming. I expressed my concerns about the fate of my father and Svechin, to which Pavel rightly pointed out that the ultimate goal of our operation should also be their freedom. I really wanted to believe him, although deep down I knew that there was vanishingly little chance of making it before the most terrible events in the history of the Soviet Union would begin...

Продолженіе слѣдуетъ — To be continued

.jpg)