Tsar L'if the Impaler

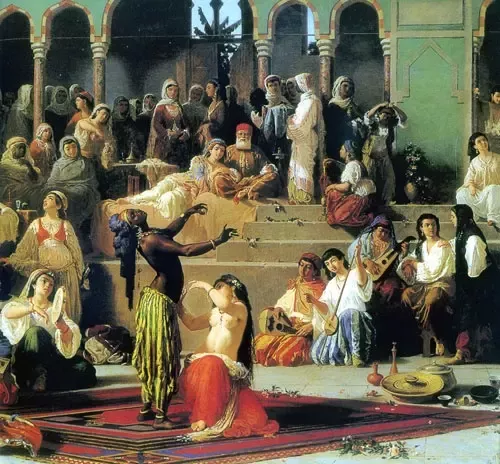

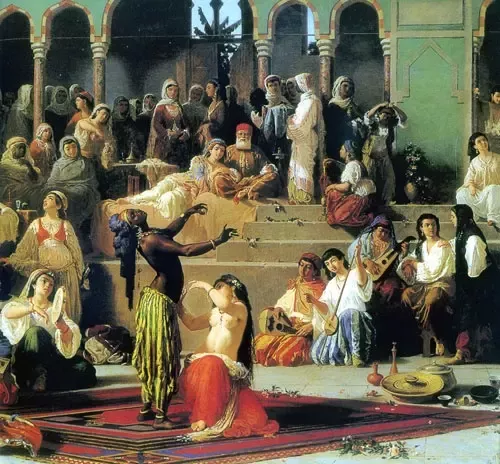

Tsar L’if and the Azovian Court

The Kuzari, full title Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion (Arabic: كتاب الحجة والدليل في نصرة الدين الذليل: Kitâb al-ḥujja wa'l-dalîl fi naṣr al-dîn al-dhalîl), also known as the Book of the Kuzarites, was completed in the year 1140 AD at the peak of the Kuzari crusades into central Europe.

The book was written by the medieval Sephardi Jewish philosopher, Judah Halevi, and is one of the most important apologias of Jewish philosophy. While most of the essays are dedicated to Jewish thinking and religious traditions, it uses a literary device of a conversation between an unnamed legendary Kuzarite King and a Jewish Rabbi on the tenets of Judaism and the rabbi’s attempts to correct the King on astray Kuzarite practices such as the toleration of pagan practices, mystical kaballah rituals and the acceptance of adultery by the Azovian people. Setting aside the theological contents, the setting of the book is useful in illuminating the nature of the Azovian court.

Scholars speculate that the King in question is the Tsar L’if. A talented duelist in his youth and the embodiment of knez-hood, tales of the tall and handsome prince greatly enhanced the prestige and glamour of Tsaritsa’s court but behind that chivalrous demeanour was a man who was not used to being refused.

Tsaritsa Quna’s children, her sons L’if and Ezra and three daughters, Devorah, Sarah and Yigid enjoyed the best education that the riches of Azov could afford, and excelled at horse riding, hunting and Azovian courtly practices. While Quna was vicious with her enemies, she was lenient with her family. As they grew into adulthood, Ezra prepared to take on the traditional role of Nasi that the Kozar family had been practicing for generations while the daughters were given court duties. However, marriage was refused for them by the Tsaritsa who had seen the dangers of rival claimants and the support they could gather among unhappy lords during the reign of her father and during her ascension. She wanted to ensure that no such troubles would bother her heir, L’if.

Rumours soon spread in the court that the five siblings had carnal knowledge of each other. Azovians were still new to sedentary life and sex outside marriage did not have the same stigma that it carried in the Christian West. Kuzarite customs dictated that no child could be born a bastard and fornication was not a sin but when the first child of Sarah was born a dwarf, everyone knew it was a child of incest. It was not the last grandchild of sin for Quna and Sarah would bear four more children, with two more accursed with dwarfism. These are the grandchildren that Quna refused to ransom back from King Wezrej, though the Princes L’if and Ezra never claimed any of them as their own.

Beyond the debauchery in the royal household, the court of Kiev played host to wild feasts and an embarrassment of decadent food from across the empire of the steppes. Courtiers would be found fornicating in side chambers and horses stormed through the feast hall. Christian monks maliciously reported that the Azovian people were horse breeders in more ways than one. While the stories out of Quna’s palace turned away the chaste and pious, it attracted many revelers and free spirits who gladly served the Tsaritsa in return for her patronage. Much of the colour described within the Kuzari fit with what we know of Quna's and L'if's imperial court and fit with the description of other visitors.

Beyond the debauchery in the royal household, the court of Kiev played host to wild feasts and an embarrassment of decadent food from across the empire of the steppes. Courtiers would be found fornicating in side chambers and horses stormed through the feast hall. Christian monks maliciously reported that the Azovian people were horse breeders in more ways than one. While the stories out of Quna’s palace turned away the chaste and pious, it attracted many revelers and free spirits who gladly served the Tsaritsa in return for her patronage. Much of the colour described within the Kuzari fit with what we know of Quna's and L'if's imperial court and fit with the description of other visitors.

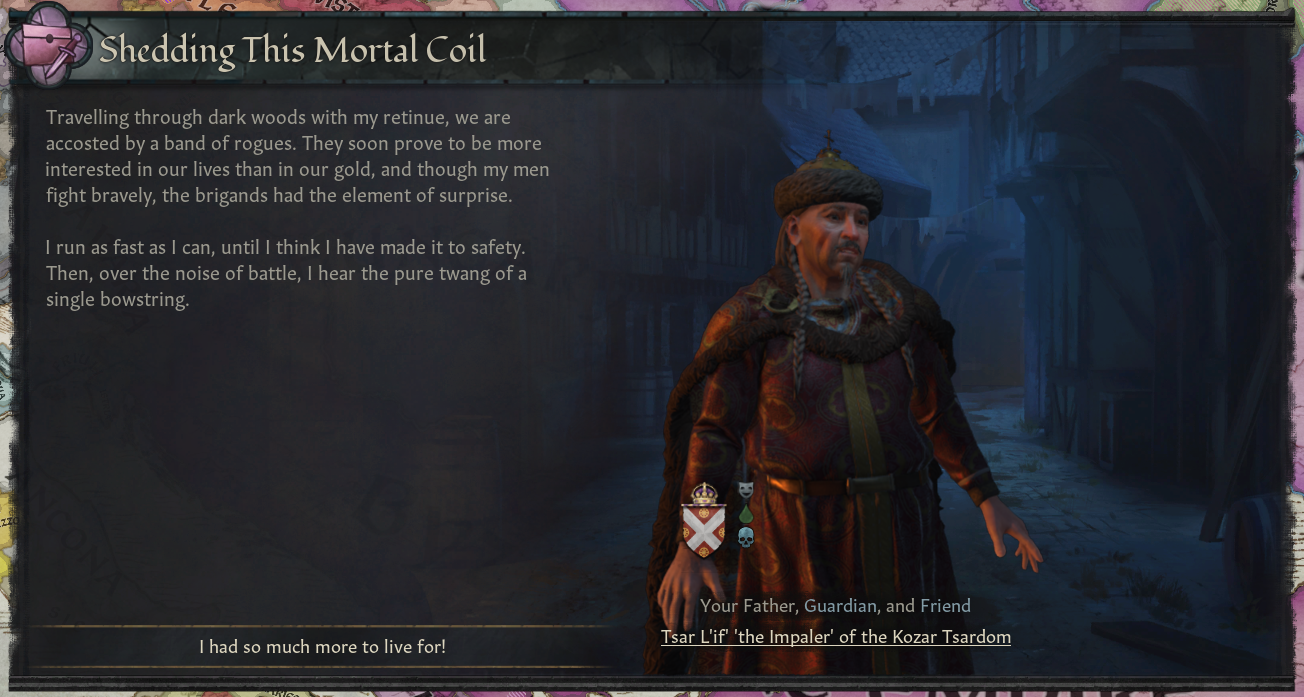

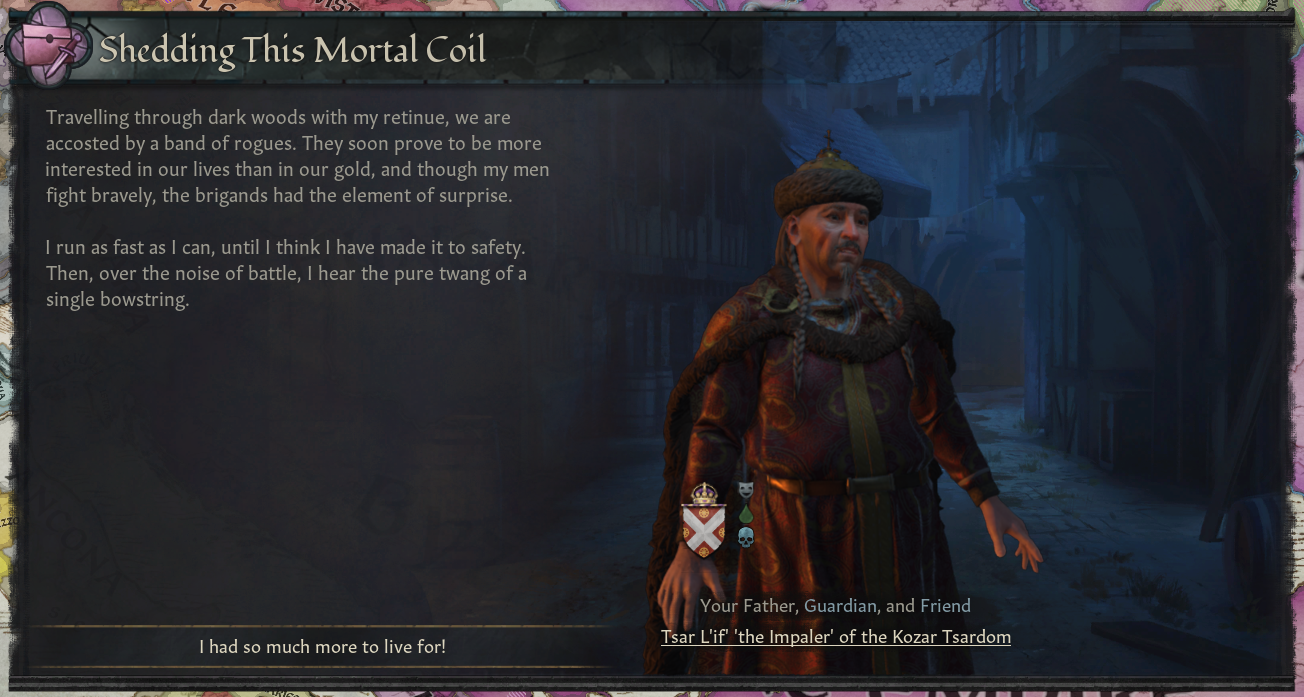

And so, we come to the reign of Tsar L’if who was a learned man but not a pious one. Upon his ascension, he ordered the dungeons to be cleared of his mother’s many prisoners of war as he intended to start his own collection. Ignoring the accusations of murder, sodomy, inebriety and incest, Tsar L’if had grand plans to build upon his mother’s legacy. What he should not have ignored are the many enemies he had made during his long prince-hood.

It was three years into his reign and he was leading one of the now annual raids into Byzantine territory when his enemies struck. The raiding force was deep inside Thrace and the Basileus had mobilized a force to stop it. Tsar L’if was out scouting with a small force when he was set upon. A single arrow in his eye laid the Tsar low and the Romans came upon the disorganized encampment and routed the leaderless Azovians, with only half of his 7,000 men making it back home.

He had only one true-born child, Princess Ulita, all of 15 years, now Tsaritsa of a sprawling empire forged by her grandmother, a treasury depleted by her father’s ambitions and a host shattered by a vengeful Basileus.

The Kuzari, full title Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion (Arabic: كتاب الحجة والدليل في نصرة الدين الذليل: Kitâb al-ḥujja wa'l-dalîl fi naṣr al-dîn al-dhalîl), also known as the Book of the Kuzarites, was completed in the year 1140 AD at the peak of the Kuzari crusades into central Europe.

The book was written by the medieval Sephardi Jewish philosopher, Judah Halevi, and is one of the most important apologias of Jewish philosophy. While most of the essays are dedicated to Jewish thinking and religious traditions, it uses a literary device of a conversation between an unnamed legendary Kuzarite King and a Jewish Rabbi on the tenets of Judaism and the rabbi’s attempts to correct the King on astray Kuzarite practices such as the toleration of pagan practices, mystical kaballah rituals and the acceptance of adultery by the Azovian people. Setting aside the theological contents, the setting of the book is useful in illuminating the nature of the Azovian court.

Scholars speculate that the King in question is the Tsar L’if. A talented duelist in his youth and the embodiment of knez-hood, tales of the tall and handsome prince greatly enhanced the prestige and glamour of Tsaritsa’s court but behind that chivalrous demeanour was a man who was not used to being refused.

Tsaritsa Quna’s children, her sons L’if and Ezra and three daughters, Devorah, Sarah and Yigid enjoyed the best education that the riches of Azov could afford, and excelled at horse riding, hunting and Azovian courtly practices. While Quna was vicious with her enemies, she was lenient with her family. As they grew into adulthood, Ezra prepared to take on the traditional role of Nasi that the Kozar family had been practicing for generations while the daughters were given court duties. However, marriage was refused for them by the Tsaritsa who had seen the dangers of rival claimants and the support they could gather among unhappy lords during the reign of her father and during her ascension. She wanted to ensure that no such troubles would bother her heir, L’if.

Rumours soon spread in the court that the five siblings had carnal knowledge of each other. Azovians were still new to sedentary life and sex outside marriage did not have the same stigma that it carried in the Christian West. Kuzarite customs dictated that no child could be born a bastard and fornication was not a sin but when the first child of Sarah was born a dwarf, everyone knew it was a child of incest. It was not the last grandchild of sin for Quna and Sarah would bear four more children, with two more accursed with dwarfism. These are the grandchildren that Quna refused to ransom back from King Wezrej, though the Princes L’if and Ezra never claimed any of them as their own.

And so, we come to the reign of Tsar L’if who was a learned man but not a pious one. Upon his ascension, he ordered the dungeons to be cleared of his mother’s many prisoners of war as he intended to start his own collection. Ignoring the accusations of murder, sodomy, inebriety and incest, Tsar L’if had grand plans to build upon his mother’s legacy. What he should not have ignored are the many enemies he had made during his long prince-hood.

It was three years into his reign and he was leading one of the now annual raids into Byzantine territory when his enemies struck. The raiding force was deep inside Thrace and the Basileus had mobilized a force to stop it. Tsar L’if was out scouting with a small force when he was set upon. A single arrow in his eye laid the Tsar low and the Romans came upon the disorganized encampment and routed the leaderless Azovians, with only half of his 7,000 men making it back home.

He had only one true-born child, Princess Ulita, all of 15 years, now Tsaritsa of a sprawling empire forged by her grandmother, a treasury depleted by her father’s ambitions and a host shattered by a vengeful Basileus.

Last edited:

- 1