Otemis 'the White Lion' of Azov'

Not much is known of the origins of King Otemis – some sources state he was a bodyguard of the Khazari Khan who was rewarded with the lands of Northern Azov for his service while others speculate he had escaped the Abbasids slave soldier army. The earliest date his name appears in the histories is 867AD when it first mentions a Chief Otemis of Azov and Khumbar conducting raids into Byzantine Kerch and the Georgian kingdoms of the Caucasus. Excelling at warfare and raiding, he brought back much treasure and slaves to Khazaria throughout the late 9th century and began encroaching on Abkhazia territory over the late 9th century, after capturing the Caucasian Gates of Darial in 879AD.

Otemis was had grown important in the esteem of the Khazar Khan and he was given the title of High Chief, and rights to the prosperous trade colony of Tmuratakan and the Radhanites merchants in control there. The Radhanites chaffed at this closer degree of control by someone they viewed as a barbarian because while the Khazars were nominally Jewish, they were not of the people and many steppe customs had been integrated into their religious practrces. Tensions built up between the urban orthodox Radhanites and the nomadic Khazars on trade taxes and in 883, full insurrection broke out while Duke Otemis was away on a raid deep in Byzantine Trebizond. The Radhanites moved too slow to complete the siege of the High Chief's stronghold in Abkhazia and the Otemis raiding force of nearly 1,000 horse swept over the lightly armed and trained Jews. After the battle, Otemis consolidated his rule in Azov, removing the Radhanites from Tmuratakan and sponsoring preachers to spread Kuzarite doctrine and practices in the orthodox Jewish community.

While Otemis fulfilled his duties as the protector of Khazaria’s southern borders, two great conquerors arose in the West, Arpad Arpad of the Magyars and Rurik Rurikid of Novgorod waged wars of conquest in Khazaria’s Russian territories until the Khan was left with only the lands East of the Volga and the Caucasus but a reprieve came in 907 when the Magyars abandoned their holdings in Zaporizhia in a great migration for the more prosperous and fertile lands of Pannonia after the Bulgarian state collapsed in the early 10th century. It was too late for Jewish Khazaria though and the Empire dissolved with the ascension of Khan Imil who returned to pagan Tengri practices after witnessing the failures of his father’s reign and the little protection the word of god provided him.

The next decade saw the newly independent Otemis consolidate his power in Azov and the surrounding regions, defeating the Alani, the remaining Abkhazians, and most famously ejecting the Byzantines from their long-held outpost in the Crimea, while the Greeks were undergoing another period of civil war and unable to muster its full might against Otemis’ army, now supported by conscripted Georgian Monaspa and Adyghean Horse Archers.

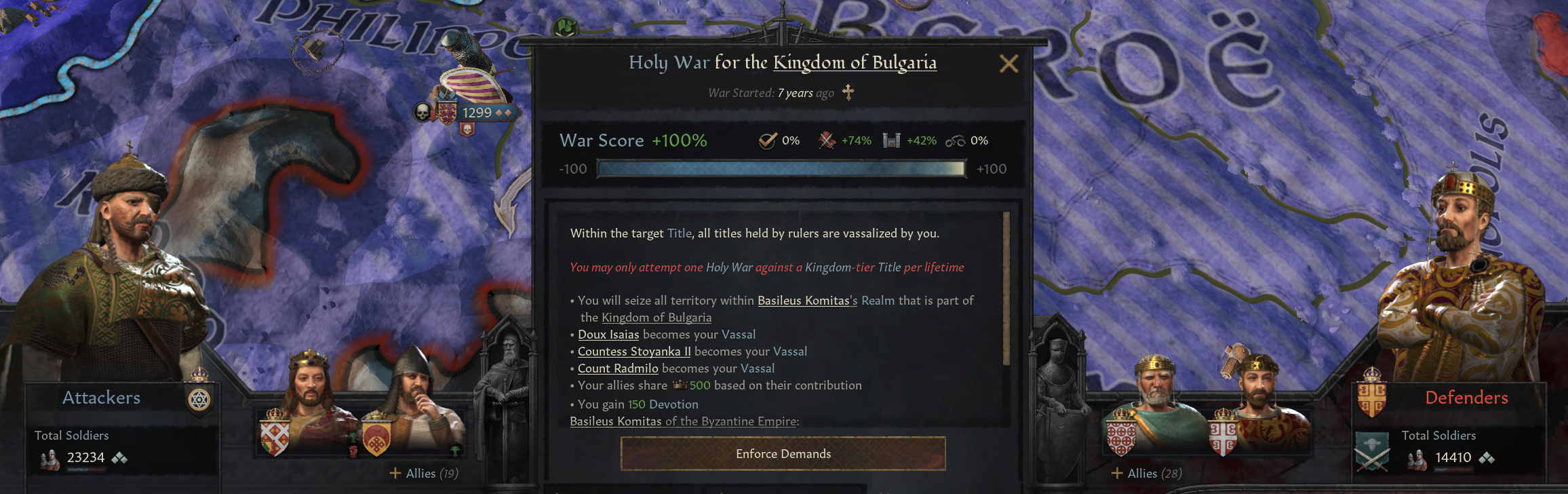

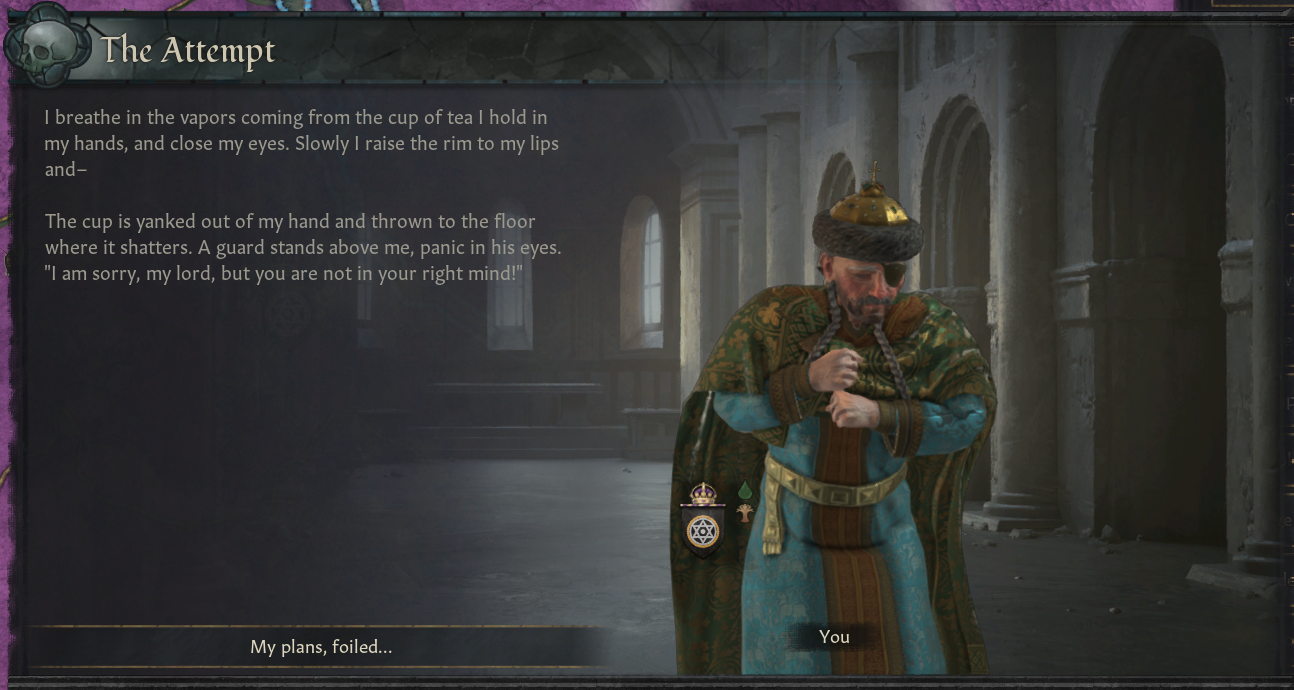

11th century depiction of Otemis as a warrior king. Later histories and portraits leave out his albinism but all older sources affirm his epithet of the White Lion.

The historical borders of the Khanate of Azov with its capital at Tmuratakan.

Not much is known of the origins of King Otemis – some sources state he was a bodyguard of the Khazari Khan who was rewarded with the lands of Northern Azov for his service while others speculate he had escaped the Abbasids slave soldier army. The earliest date his name appears in the histories is 867AD when it first mentions a Chief Otemis of Azov and Khumbar conducting raids into Byzantine Kerch and the Georgian kingdoms of the Caucasus. Excelling at warfare and raiding, he brought back much treasure and slaves to Khazaria throughout the late 9th century and began encroaching on Abkhazia territory over the late 9th century, after capturing the Caucasian Gates of Darial in 879AD.

Otemis was had grown important in the esteem of the Khazar Khan and he was given the title of High Chief, and rights to the prosperous trade colony of Tmuratakan and the Radhanites merchants in control there. The Radhanites chaffed at this closer degree of control by someone they viewed as a barbarian because while the Khazars were nominally Jewish, they were not of the people and many steppe customs had been integrated into their religious practrces. Tensions built up between the urban orthodox Radhanites and the nomadic Khazars on trade taxes and in 883, full insurrection broke out while Duke Otemis was away on a raid deep in Byzantine Trebizond. The Radhanites moved too slow to complete the siege of the High Chief's stronghold in Abkhazia and the Otemis raiding force of nearly 1,000 horse swept over the lightly armed and trained Jews. After the battle, Otemis consolidated his rule in Azov, removing the Radhanites from Tmuratakan and sponsoring preachers to spread Kuzarite doctrine and practices in the orthodox Jewish community.

While Otemis fulfilled his duties as the protector of Khazaria’s southern borders, two great conquerors arose in the West, Arpad Arpad of the Magyars and Rurik Rurikid of Novgorod waged wars of conquest in Khazaria’s Russian territories until the Khan was left with only the lands East of the Volga and the Caucasus but a reprieve came in 907 when the Magyars abandoned their holdings in Zaporizhia in a great migration for the more prosperous and fertile lands of Pannonia after the Bulgarian state collapsed in the early 10th century. It was too late for Jewish Khazaria though and the Empire dissolved with the ascension of Khan Imil who returned to pagan Tengri practices after witnessing the failures of his father’s reign and the little protection the word of god provided him.

The next decade saw the newly independent Otemis consolidate his power in Azov and the surrounding regions, defeating the Alani, the remaining Abkhazians, and most famously ejecting the Byzantines from their long-held outpost in the Crimea, while the Greeks were undergoing another period of civil war and unable to muster its full might against Otemis’ army, now supported by conscripted Georgian Monaspa and Adyghean Horse Archers.

11th century depiction of Otemis as a warrior king. Later histories and portraits leave out his albinism but all older sources affirm his epithet of the White Lion.

The historical borders of the Khanate of Azov with its capital at Tmuratakan.

Last edited:

- 1