Chapter 2: The Empire at war.

Part 1: The Happy times.

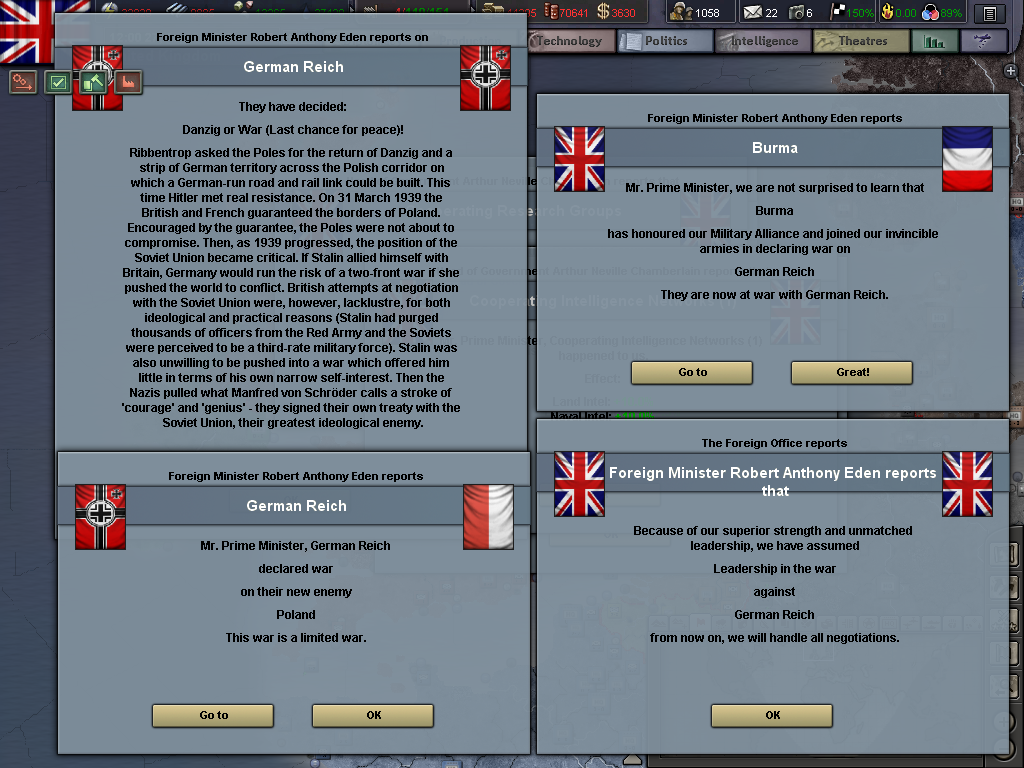

Late on August 27th 1939 the German Reich declared war on Poland, with waves of troops immediately launching themselves over the border. Polish troops had noticed the massing and positioned themselves in preparation of the assault, but there was ultimately little they could do against the much larger and mostly better equipped German army. Though they bled their enemy, they were generally overwhelmed.

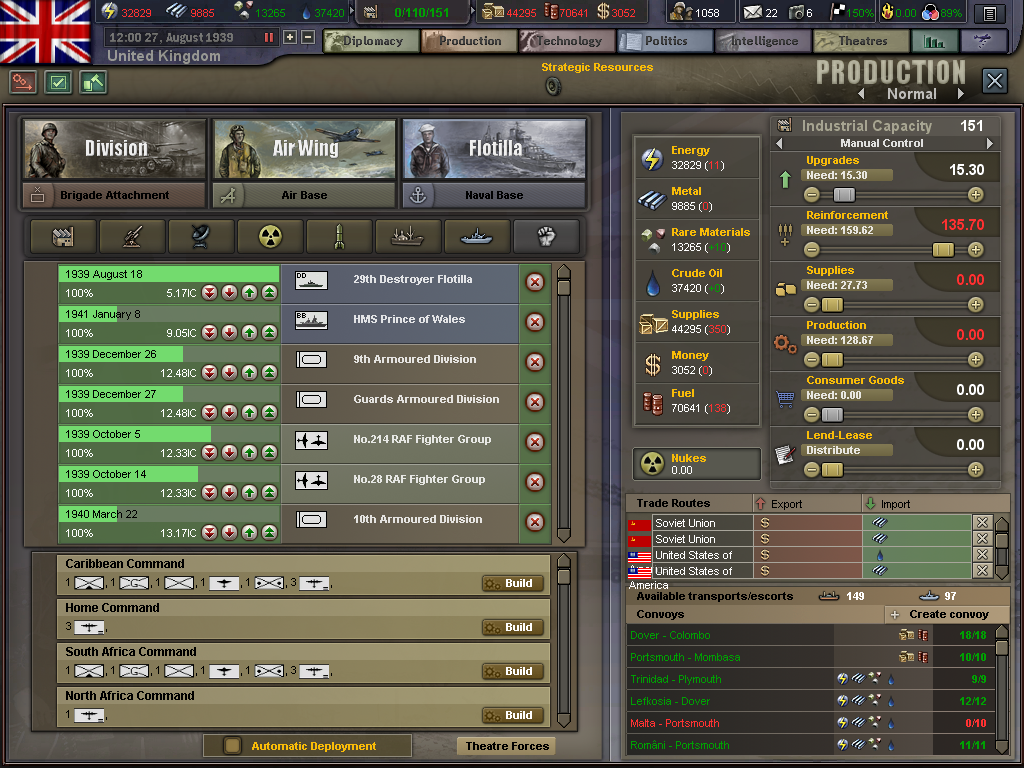

It wasn't until August 28th that a formal declaration of war was announced between the British Empire and Germany, but immediate alerts went out to the Royal Navy and Airforce to recall all personnel and the army received orders to recall all reserve troops on short notice, which were put into effect on noon of the 28th. This meant that Britain was ready for immediate defensive and offensive naval action, with available air cover from both the RAF and the RN's carriers ready to do whatever was needed. The army was prepared in the large sense, but needed to bring all of its formations up to strength, which was the main focus of the government in the coming weeks as they were unsure if the Germans would try to blitz France at the same time as Poland.

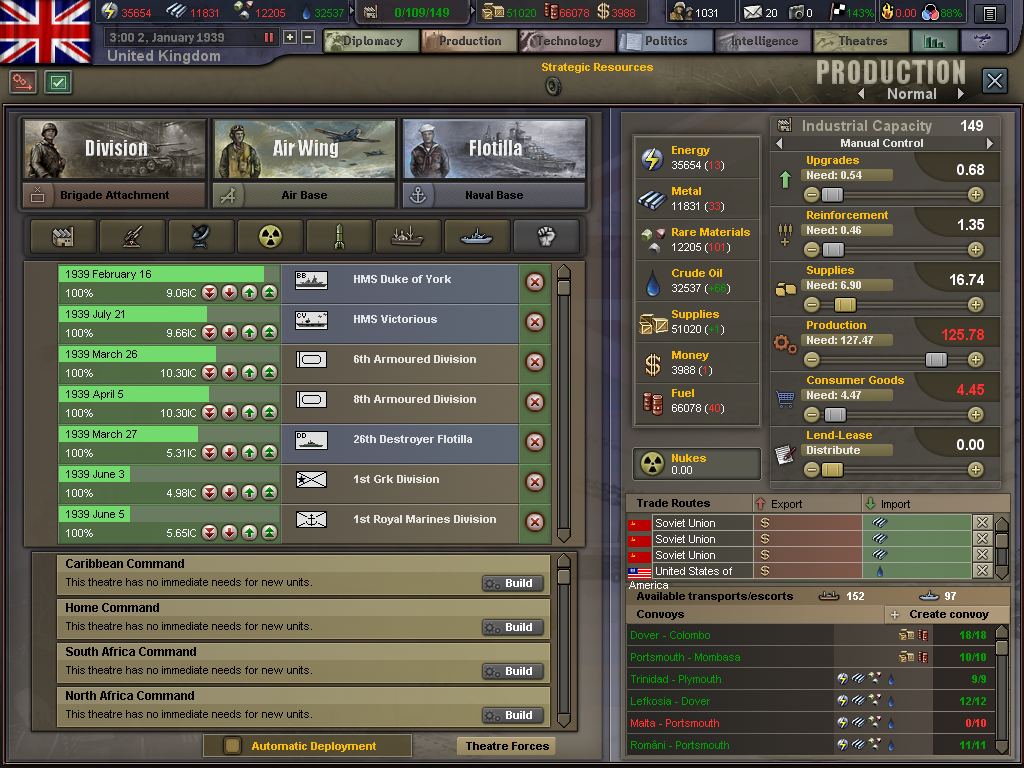

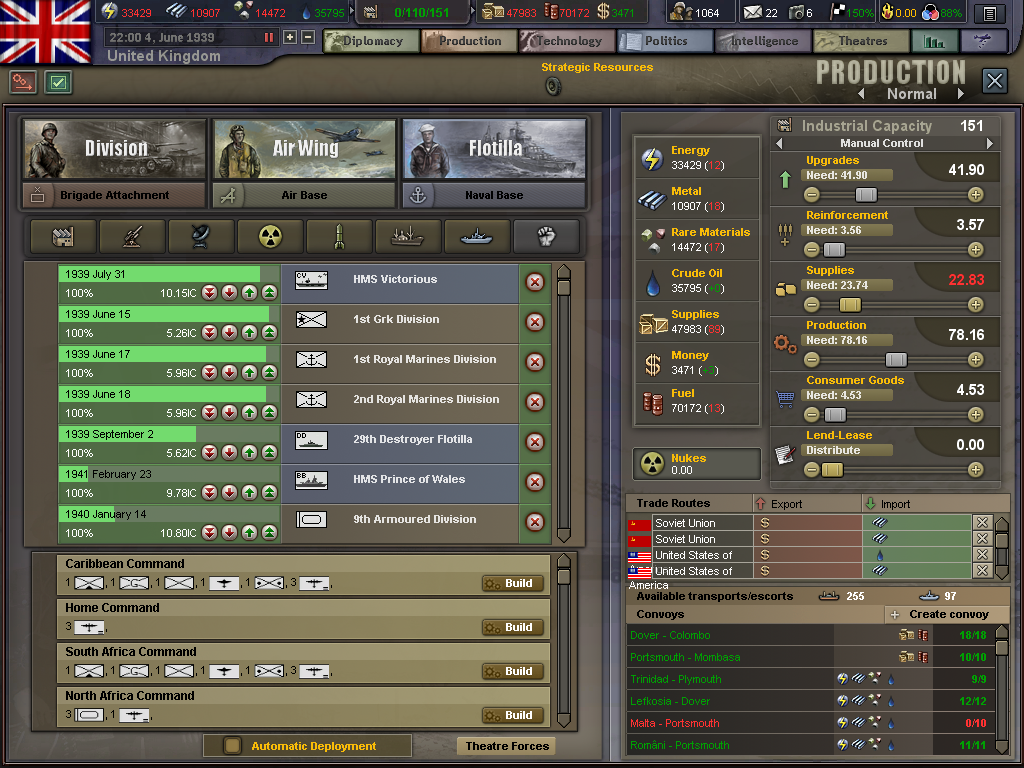

Production on new forces was temporarily disrupted as men from all walks of life were called up to their army.

The first clash of battle between British and German forces happened later in the day on August 28th, barely after a formal declaration of war between the two countries cleared the cables between them. British radio intercept technicians, who had long since cracked German naval codes, intercepted orders for a German task-force containing a number of large surface ships to move down the Dutch coast and past Amsterdam, presumably as a warning to the government to stay out of the developing conflict. Taking advantage of the Royal Navies already staffed and ready ships the admiralty ordered and immediate sortie of of both the Fast Battleship task-force and the Battlecruiser task-force to intercept the German ships.

Shortly after 2:15 PM on the 28th, the Fast Battleship task-force under Admiral Sir James Sommerville was at the entrance the Ijsselmeer in pursuit of what had been determined to be the German Battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the heavy cruiser Graf Spee and about ten destroyers. Having already passed by then Dutch coast and on their way out, the German task-force was taken under long range fire by all four Battleships. Completely outgunned Admiral von Nordeck the commander of the German ships ordered them to flank speed in an attempt to flee. While the correct decision, von Nordeck had underestimated the speed of the British ships. Though his ships were faster than the British, it wasn't enough to get them out of range quickly as Admiral Sommerville had placed his ships in the perfect position.

For over an hour von Nordeck's ships had to endure fire from the British ships. The German ships became strung out after a few minutes as von Nordeck had ordered max speed to all vessels, which all had different top speeds. As the battle ran on, each of the German ships was taken under fire in turn. All ten destroyers were destroyed one by one, most never even able to return fire. Graf Spee attempted to screen some of the smaller ships, but fire from two of the British battleships quickly bracketed her and smashed her to pieces though a few shots fired managed to damage HMS Penelope, the only cruiser in the task-force. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau both traded shots with the larger British vessels, Gneisenau taking several hard hits but not losing speed. Eventually both of the pocket Battleships managed to make it out of the range of the British ships, but the rest of the ships were all either burning or sunk along the Dutch coast.

Though the British lost no ships, she lost several dozen sailors from hits landed by the Germans. The first men lost by the Empire in this war, they would not be the last.

Having just one a victory and wary of German planes attacking his ships in constricted waters, Sommerville withdrew after it became clear that the German ships could not be caught. Sailing back into port Sommerville's task-force was met by cheering crowds, Union Jacks waving in the wind. Though a small victory, it was one that seemed to prove that the British Empire was more than ready for the coming war.

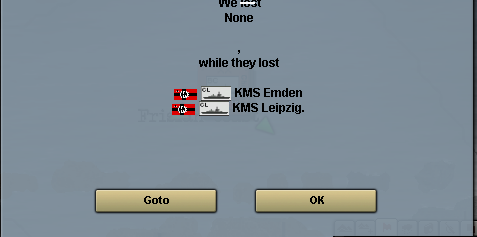

Further victories later the next day as Hood, Renown and Repulse along with their light cruiser escorts met three German light cruisers and their destroyer escorts, sinking two with little damage to themselves, only further increased the British morale. When combined with the quick Canadian declaration of war on the 4th of September and a massive wave of Indian volunteers as the news reached the Dominion, British opinion of the war was riding high.

The greatest and most daring victory for the Royal Navy came a week and a half later, as Admiral Sommerville once again received information from British intercepts, this time accompanied by reports from British submarines, of further German naval movements. A large task-force was moving from German Baltic bases to Wilhelmshaven in an attempt to gather their forces and threaten British shipping. Sailing out in the early morning hours his taskforce managed to intercept the German one, though it was dangerously close to the German coast. Containing the two aging

Deutschland class battleships leftover from the Great War as well as a cruiser and over a dozen destroyers, the task-force is completely surprised by the British ships.

Admiral Raeder as the commander of the German ships immediately ordered the smaller German ships to flee, while he took the two aging and slow ships around in an attempt to slow the British fleet. Unfortunately for Raeder several of his ships refused to abandon him. Charging the British ships the Germans fired repeatedly, but managed no hits due to their older guns and rangefinders. British fire bracketed the Germans and several hits were landed, but they refused to go down. In a simultaneously daring and dangerous move, the Commander of the British 13th Destroyer flotilla, Captain Charles Saumarez Daniel ordered his ships to close to torpedo range. Dodging German fire, the four destroyers launched a tight spread of torpedo's at relatively close range. Unable to maneuver quickly enough to dodge, both of the German battleships took several torpedo hits and began to sink. As German sailors began to abandon ship, Admiral Raeder found himself put in a lifeboat and forced towards one of the German destroyers by his crew, saving him from British captivity. In the end, the Germans had lost two Battleships, another light cruiser and five destroyers.

The 13th Destroyer flotilla unofficially became known as the "Battleship Killers" after the battle.

Following the battle, the British once again retired back to base triumphant, secure in the knowledge that much of the German fleet was already at the bottom of the North Sea. This triumph was dulled somewhat as news came shortly after that Italy and her relatively strong and modern Regia Marina had joined with Germany. Though there was no declaration of war between the two nations, it seemed inevitable that they would soon clash.

Despite the news morale remained high, as the Royal Navy had again proved its dominance of the sea.

Though the rest of the month was relatively quiet, though there were several attacks on British merchant shipping by German submarines. In return, the Germans paid heavily for their victories as British ASW groups and escorts pounced with their advanced detection gear and anti-submarine weapons. Over a dozen German submarines were confirmed sunk in that time, some with help from the French navy.

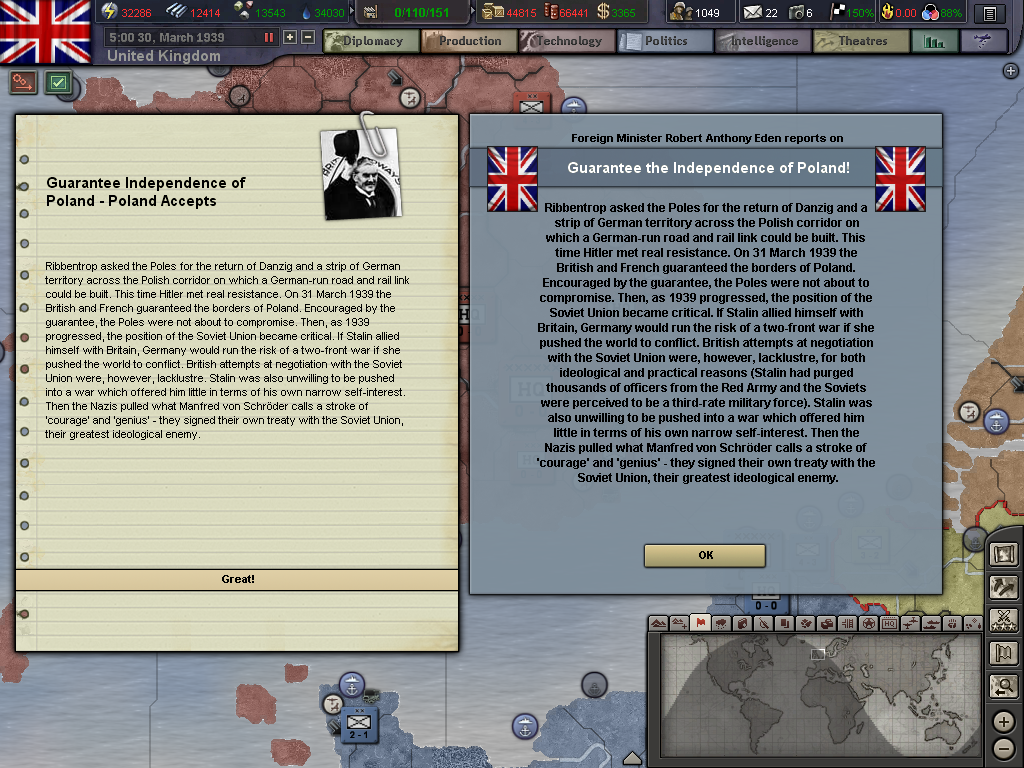

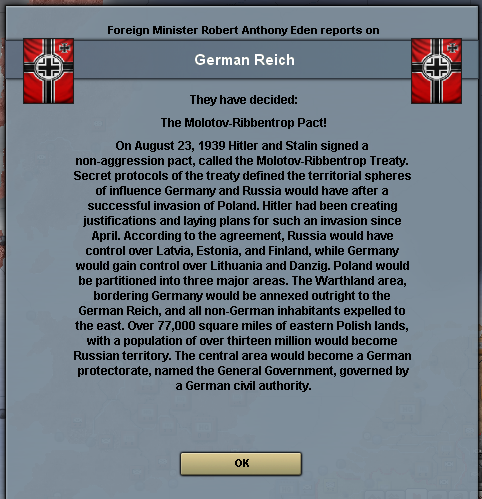

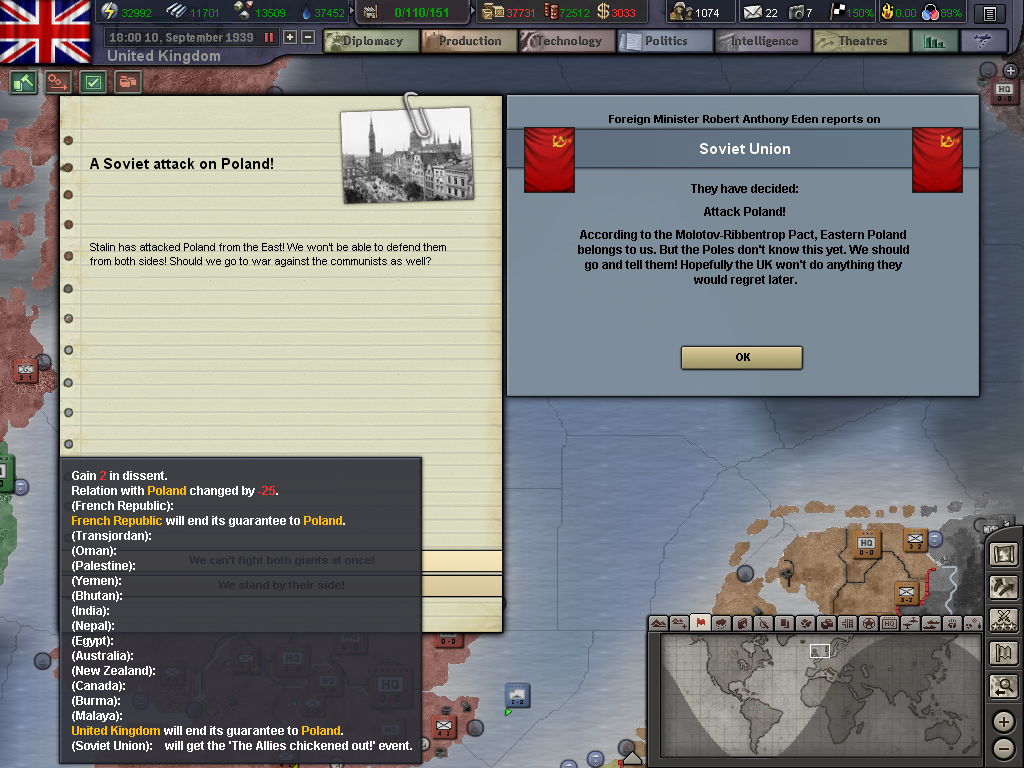

Even as that good news spread, there was bad news coming from Poland. Even as the British called up forces and retrained reservist members, the Polish Army was being pushed back by the Germans. Even with French support, there was little that could be done to stop them as much as some planners in the British General staff wanted to send the ready units of the army to try and aid the Polish. With Danzig falling withing only a few days, there was nowhere for the British to land without fighting and she didn't have enough ready divisions to force a landing. Following the Soviet declaration of war on Poland following shortly after, there was nothing that could be done and the government fell to Realpolitik and gave up all hope of saving the Poles.

Though brave Polish forces were outnumbered and outgunned by the aggressive German army.

Though the RAF landed several air attacks on German facilities in the western part of the country, in the east there was nothing they could do even as the Polish armed forces collapsed. Like a building falling, there was nothing that could be done to stop it and on the 25th of September Poland capitulated to Germany.

Though some Poles escaped to the Isles, most were understandably bitter about the lack of help their country received.

Later the next day mixed news came in from the fleet. HMS Argus and its destroyer escorts had been patrolling southwest of England on ASW duty when a task-force again containing Scharnhorst and Gneisenau along with several escorts tried to sneak through the channel. Encountering them in a spread out dispersion, Argus and her escorts came under fire from the larger German ships. Though several hits were taken by the British, Argus managed to launch torpedo bombers which managed to damage the German ships and several destroyers closed in on Gneisenau, which hadn't been fully repaired from her earlier fight with Sommerville's Battleships and was slower than the others. Taking several torpedo hits she foundered and was left behind by her sister ships as they continued to dash through the Channel. British destroyers picked up the survivors, taking them back to base as the destroyers escorted the Argus in for repairs.

Despite heavy damage, Argus managed to make Portsmouth under her own power.

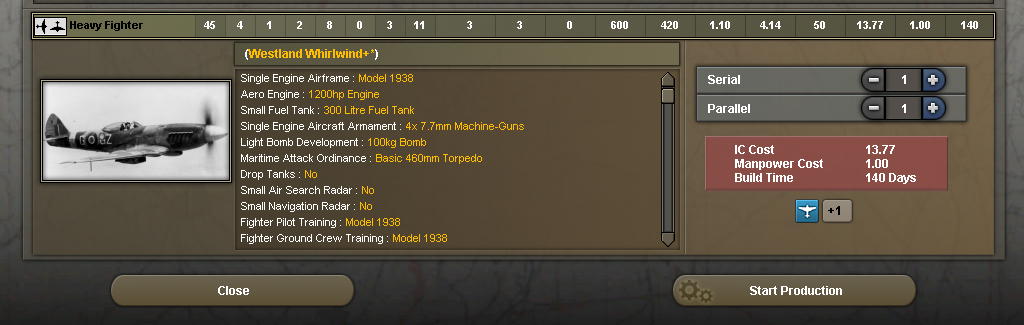

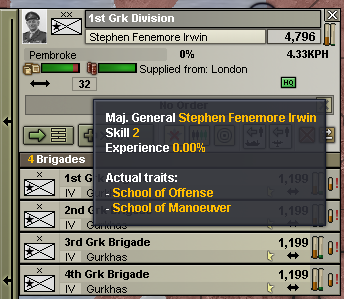

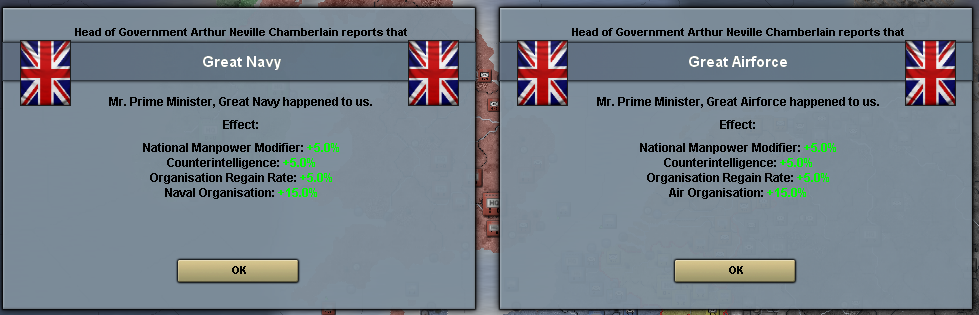

Several days later, the General staff, in response to government demands of reassurance of Britain's readiness for the war, introduced the new specialist training program, which called for much higher standards on British officers and men in return for increased training time. Britain couldn't match the Germans for quantity on the ground, even with help from her dominions, so she would have to fight with quality.

British men would be the best trained in the world, they couldn't afford anything else.

October found Germany declaring war and occupying Denmark in only a few days, the government quickly capitulating in face of overwhelming German military power. Britain had no time to do anything for her people, much less stop the Germans. A few Danish ships sought refuge in British ports, but other than that most Danes seemed to accept their position as a veritable German province.

As the month of October passed with little fighting aside from occasional air sorties back and forth, the British people began to realize that this would be another long and hard war, just like the previous Great War. German and French troops stared each other down from their border fortifications, neither side moving an inch. The General staff had sent the 1st Infantry corps in order to hold the British and French mutual support, but for the moment everything else seemed quiet as debate raged on what else to do with the British army and her tanks, which many felt would be wasted behind fortifications.

Early November found the British people buckling down and preparing for the long run. Factories ran 24 hours a day, every shift filled with newly trained workers. People bought war bonds, every cent promised for a tank, plane, ship or bullet. Even more than that, people simply pulled together, supporting their neighbors as sons and fathers went off to war, making sure that nothing strange happened to locked up buildings and that the Government had everything it needed to get the war won as fast as humanly possible.

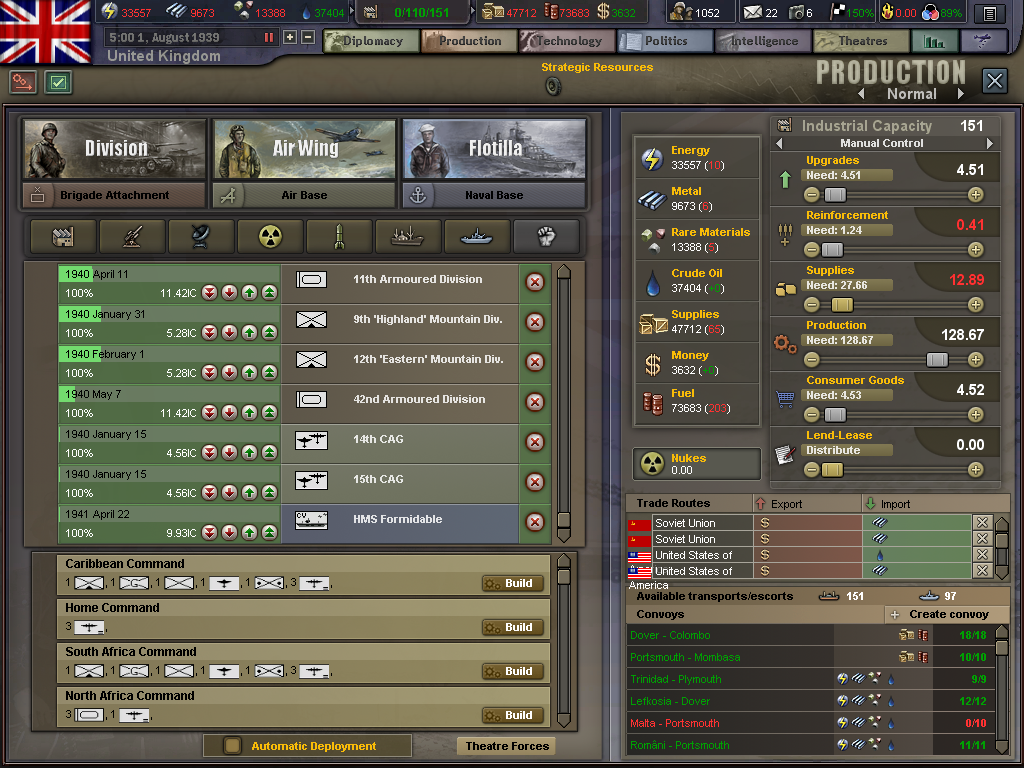

Industrial production during this time shot up massively as every sinew of the Empire was stretched towards victory.

Recruitment for the Navy and Airforce increased massively, as both services were well respected and known by the public to be the Elite of the Empire. The army lagged behind in this area, as her forces weren't as well publicized or glamorous to the average citizen, though they still benefited from the general feeling of patriotism coming from the public.

Britain was prepared to defend herself against all comers, the question was could she take the fight to the enemy.

The rest of November passed by relatively peacefully, aside from the debate that raged between the British and French general staff's on how to prosecute the war. The French expected the war to be one similar to the previous Great War, with long static lines and an eventual breakdown of German morale from starvation. They were prepared to sit behind the Maginot line as long as necessary and reinforce the Belgian forts and defensive river lines if the Germans decided to violate their neutrality once again.

The British argued against this, knowing that this Germany was unlikely to fold. There was no war with Russia, no quagmire in the East. Her population was united behind not only a powerful leader, but the desire to avenge their loss in the last war. This war would take initiative and daring to win and they couldn't afford to wait behind defenses for the Germans to fall apart on their own. Bomber command had ideas to bomb the Germans into submission, but even that would take years and with no guarantee without army support to back it up.

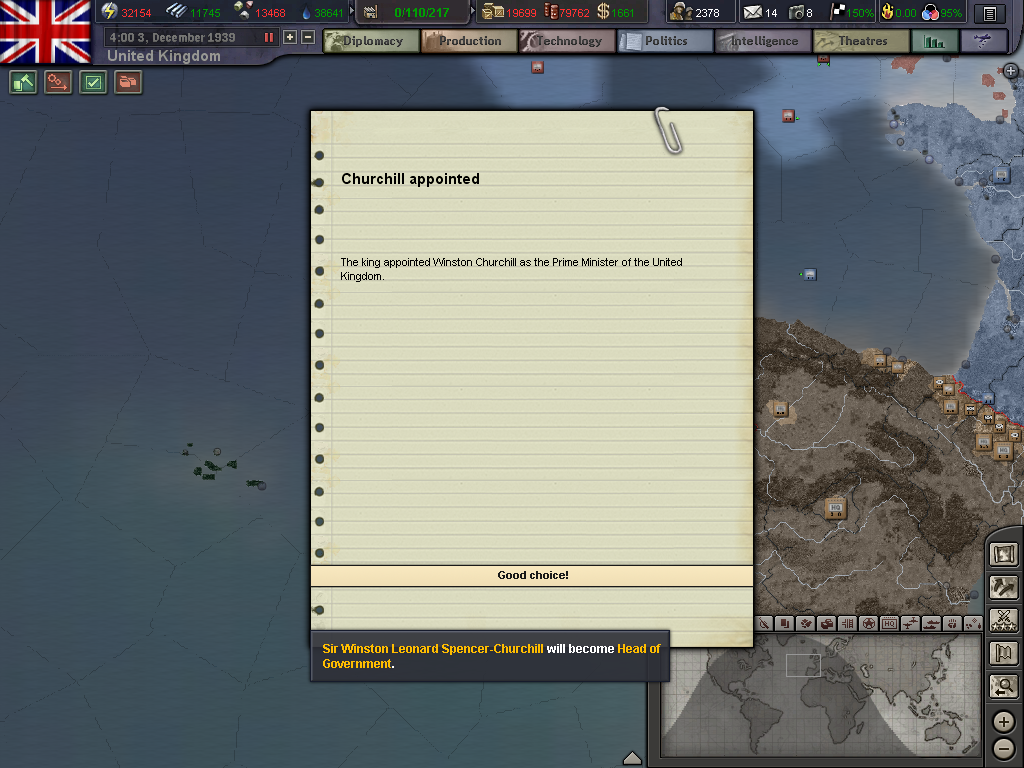

But the French would not budge and Prime Minister Chamberlain felt that he wasn't strong enough to deal with the war. After offering the position to Lord Halifax, who turned it down, the position was offered to the Conservative Firebrand Winston Churchill, who had been one of the first to join on King George's rearmament campaign. Offered the position late in the day on December 2nd, Churchill formally accepted the position in an early morning meeting on December 3rd. Younger and much more eager than Chamberlain about the war, he promised to be a good leader for the British people, immediately preparing to assume his position.

Though he had been brought back into the government earlier in the year, this was Churchill's first true power position since he had left after WWI.

The next months flew by in a strange dichotomy. There was officially a war declared between three of the worlds great powers, but there was little fighting going on. The Kreigsmarine had attempted to press German strength in the North Sea, but the Royal Navy had quickly dashed all of those hopes, sinking a large portion of the German surface fleet and sinking submarines at an amazing rate thanks to advanced ASW techniques and equipment. Thoroughly chastised, the Kreigsmarine now sat in port under heavy air cover, only her submarines even attempting action against the British.

There had been no combat beyond that between the major powers, only occasional air skirmishes. Their were no developments from the front, no battles to be lost or won. It seemed like the world was at piece, but both sides knew that new fighting could break out any second. The only news came from the British homefront, where major updates in training occured for the RN and British designers pushed aeronautical theory and ground vehicle technology even further. Industrial capability and agricultural development also followed an increasing upwards trend, with production increasing amongst all fields.

British industrial power had never been higher.

Months passed by like this, with no moves by either side. Britain could do nothing without French backing directly against Germany aside from bombing. Italy hadn't formally declared war against either France or Britain and neither government wanted to increase the number of opponents they would be facing.

April found most of both armies sitting on their respective borders.

As the British General staff were despairing on ever being able to halt or even manage to hurt the German ability to wage war, the Germans suddenly opened up a new front that promised the British a place to act, even in a limited capability.