Yep, that is a plague of the game. Highly probable cause is a pilgrimage event, then suddenly there is an adamite rhomaion, whereas independent of that, balkans may go insular, islands go waldensian, then one sees an orthodox ghana, catholic tibet, and a lollardic crusader kingdom of jerusalem.

Haha! Yeah, the pilgrimage event - combined with the mechanics of faith fervour and the heretical lord conversion choice events - seem like they're deliberately designed to spread heresy.

Pheew, was almost going to invite Your friendly watchdog from fact-checkers of fictional lores, and naturally Your friendly nerdic defender of the fictional lores comes along with. Fortunately asked before that, and received a wonderful answer, saving self from a comment that would have been highly embarrassing (as if it is not already without them, sigh).

Got it, "or" as l'or de symbole Au. C'est parfait. 'aurais dû vérifier les archives héraldiques et blasons plus attentivement.

Thanks scythians, just thanks, for bringing a symbol with a species that is found nowhere near this (arbitrarily defined) continent to be used in heraldry for hundreds of years, through your goldsmithing technique and art.

It's a cool herald, nevertheless.

Yup; either that, or the (considerably more remote possibility that) Greeks had some ridiculously long tribal memories of big cats in the Balkans going back to the Holocene. Supposedly my family's crest features three of 'em.

(Or perhaps not - my surname is ridiculously common.)

I'm a little bummed that they got rid of the CoA designer between CK2 and CK3, but the options for the random CoA generator in the character design tool can actually turn out pretty cool. They did here. Believe it or not, I didn't even use the dice for this game.

SEVENTEEN

Seeds of Doubt

26 April 890

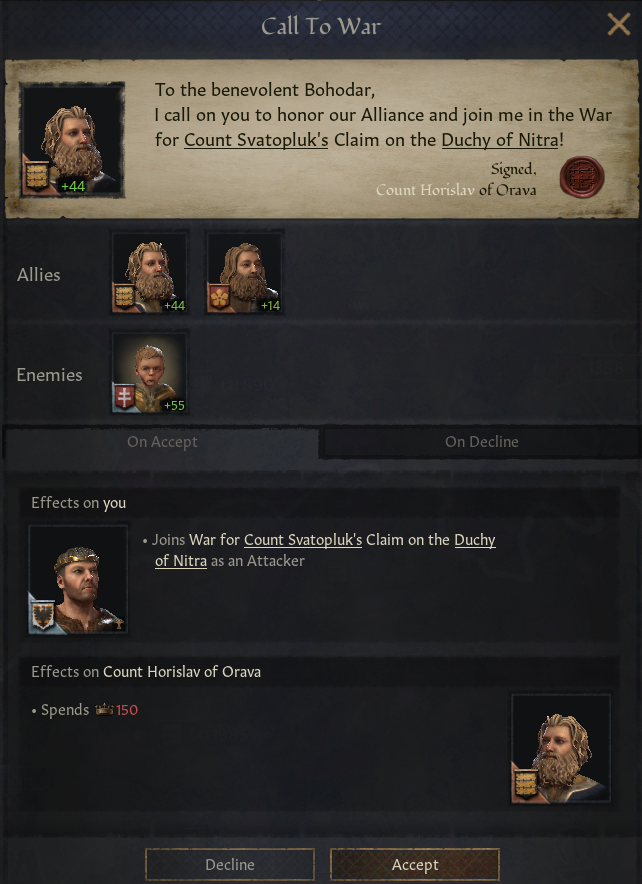

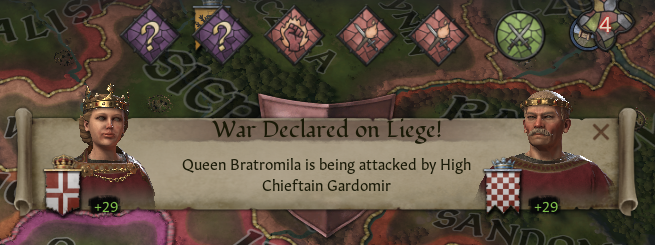

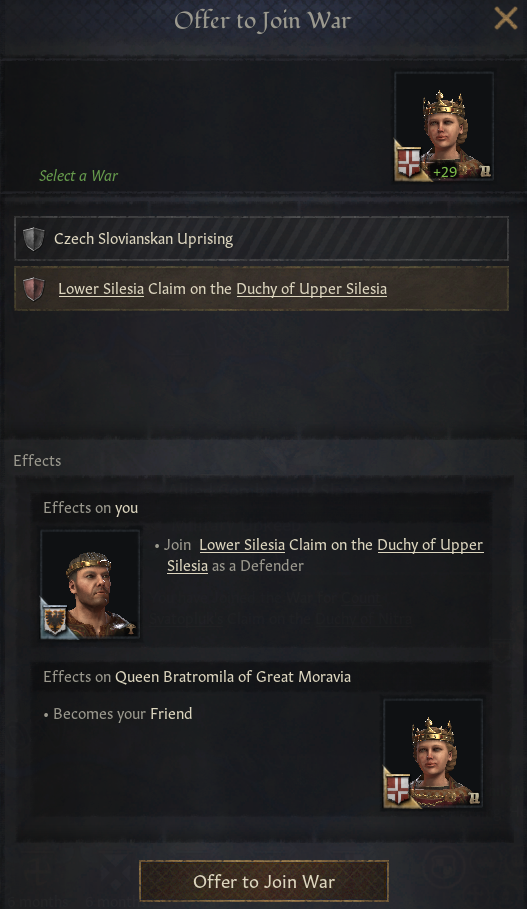

Bohodar Rychnovský returned to Olomouc in triumph from Prague. He had taken oaths of fealty from all of the Bohemian lords, both to himself and, more importantly, to Queen Bratromila. Bratromila had come in person to receive her new vassals, and they kissed her hand with all due reverence. Bohodar had thought she would be pleased at the addition of so many lands to her realm – and indeed, for much of the ceremony, she had been gracious and smiling. But there was something else on her mind, the hint of an unspoken sadness. And then Bohodar remembered: she had just recently married Chlothar of Charlemagne’s line at the insistence of her advisors… and he had not been there to object. Not that it wasn’t a politically advantageous match: the resulting alliance between Veľká Morava and Karling-ruled Italy would no doubt be a source of great strength and stability for the realm. But it was clearly not a match of love on her part, and probably not on his either. Neither of them spoke the other’s language particularly well, and what’s more, Chlothar had struck Bohodar as being a resentful and petty man – nowhere close to Bratromila’s equal in generosity or amicability.

It had been a pleasure, then, to undertake the happier duties of a godfather to the flower of the Bohemian nobility. Two of the young

hrabata of the Czechs, Róbert of Žatec and Blahomíra of Časlav, had agreed readily to be baptised… and one of the older ones, Vitislav, had agreed to do so as well after a fair bit of arm-twisting. Bohodar had agreed to personally sponsor all three of them, and had brought with him a priest from the Moravian lands to do the honours. The three Czechs were marked with the fragrant holy chrism upon their heads, necks, wrists and ankles, and then immersed fully in the waters of the Vltava along one of its quieter bends. Bohodar was sincerely moved as he heard them recite the Symbol of Faith, and it brought a tear to his eye as he remembered the holy moment of his own baptism.

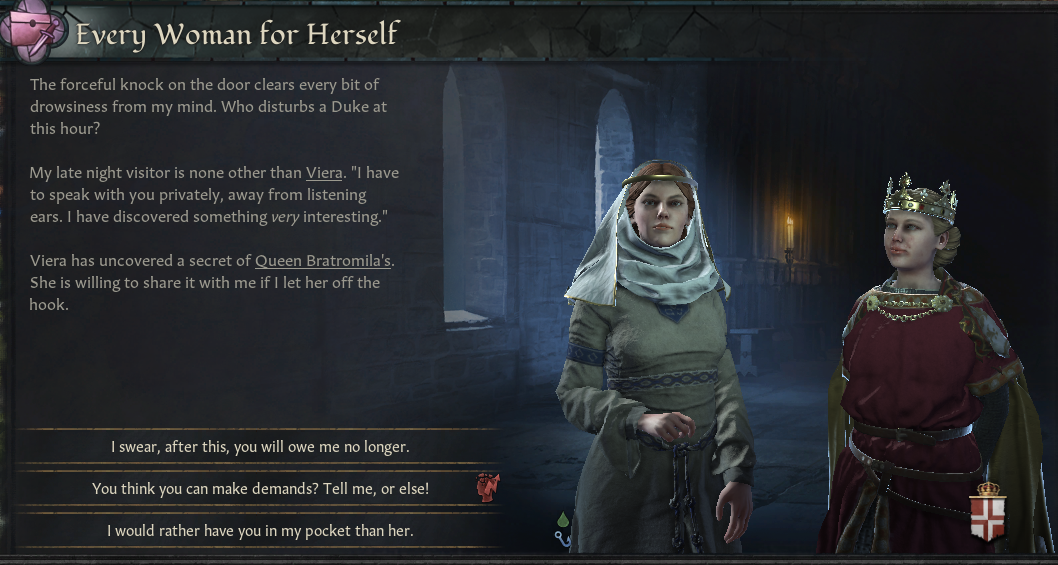

As he made his way back into his city and his fortification, though, he found waiting for him in the bailey a woman with long, stringy blond hair and a bit of a wild expression on her face.

‘

Slava Ysusu Chrystu,’ she greeted him. That was

not the standard Moravian ‘

Servus’ he had expected, but he replied in her fashion nevertheless.

‘

Slava na viki. I’m sorry, you are…?’

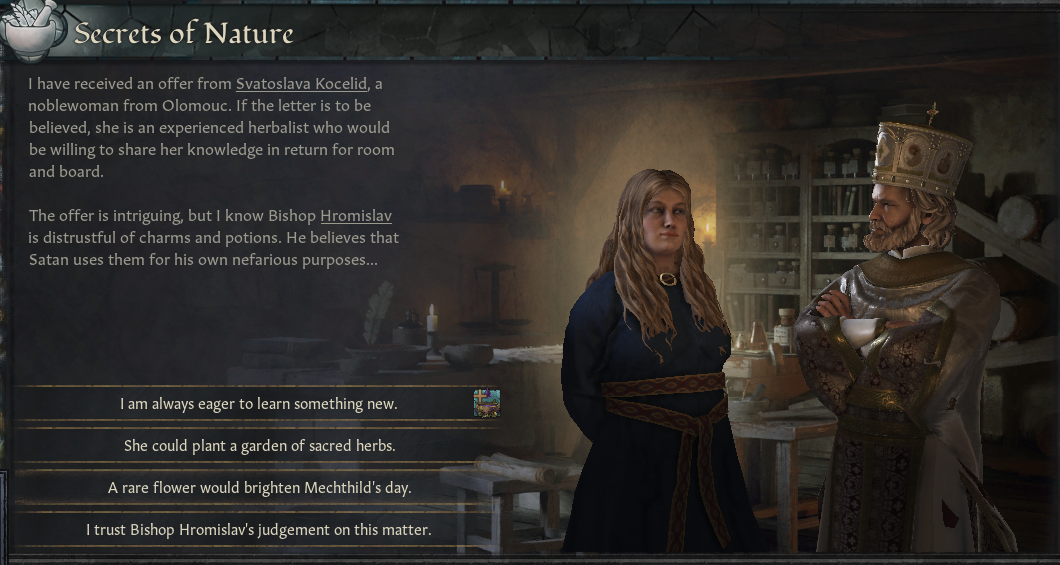

‘My name is Světoslava Koceľaková, daughter of one of the landholders in the White Croat lands,’ she replied, ‘but my name is not as important as my purpose. I have come from the mountains to the east, to offer you some of my wisdom… for a price.’

‘Intriguing,’ Bohodar answered. ‘And just what manner of wisdom do you offer?’

The woman spread wide her cloak, and reached into one of the pockets, pulling out several parts of dried and cured plants.

‘

Gestinja,’ she introduced one. ‘This will be a familiar one to you, but I can show you how the leaves can be brewed into a tea to still coughs and reduce fevers.

Krušína krechká: chewing the bark can free up your watery humours and loosen your bowels.

Šikóvča: this one’s one of my most sought-after! Stills the hot humours. Good for your liver,

and it helps ward off cancer. And those are just a few of the wares I’m willing to teach you about. I also have seeds and cuttings for you if you’d like to grow some yourself.’

It was indeed a tempting offer. Bohodar was a scholar, and the knowledge of plants was not one of his competencies as yet. But Bohodar could already see trouble looming with his new metropolitan if he began taking botany lessons from a woman like this – who may well have been an adept of the heathen arts of the

žrica which were still very much common in those parts. Still… he didn’t want to put her out altogether. She had, after all, greeted him in the name of Christ, and she was asking his hospitality, which he knew he would rue refusing.

‘Tell me,’ Bohodar asked her, ‘do you have any plants that a woman might appreciate? Flowers?’

‘Ahh,’ Světoslava grinned. ‘Something for the wife, then, or a lady friend? Of course, milord, of course! And would this woman be perhaps a

nemka?’

Bohodar inclined his head indulgently. ‘She would.’

‘In that case—‘ Světoslava produced with dramatic flair the yellowish-green stem of a flower, ending in a red-veined umbel with clusters of drooping bells of delicate pink on each terminus, ‘here’s something she’s not likely to have seen before. We call them

zimoľubka. They are not commonly seen even around my home village; they’re quite picky about where they choose to put down roots… but highly sought-after, and, as you can see, quite lovely. I can show you the best places to put them, if you want to grow them for her.’

‘I think I may take you up on that,’ Bohodar replied.

Blažena was again fixed to the spot, standing beneath that scaffold in Salzburg, looking up into the frightened, haunted, hopeless face of the condemned man she had seen there five years ago. The sky was a dirty orange, as though lit by far-off, as-yet-unseen flames. The herald, dressed – so it seemed to her – entirely in black, but with the cap of a play-actor that made two great folds on either side of his head. He was reading the list of the man’s crimes, only again Blažena couldn’t make out the words.

Then the herald turned to her with an ugly leer. The next words he spoke were fully intelligible.

‘Well, little girl?’ he asked. ‘Would you do the honours?’

Blažena felt a sharp prod in the small of her back; the German guard behind her had prodded her with the butt of his polearm. She found herself forced to ascend the wooden planks to the scaffold. Somehow the sky seemed to turn brighter and more ominous at the same time, and the whole platform was lit in a dirty orange-yellow glow.

‘Now. Let the penalty commence.’

‘I won’t do it,’ Blažena said, her voice trembling.

Again that ugly leer. ‘And who do you think you are to refuse? Your father can’t save you. He’s gone away. There is nowhere to run or hide. Besides,

you are guilty as well.’

And then she found a halter was being drawn around her own neck, and made tight. It hurt, badly. The herald’s face twisted into a sadistic smile at seeing her in pain.

‘Hm. You look much better that way,’ he sneered. ‘Now, for the crime of refusing to kill this thief, your punishment shall be the same as his. And your damnation will be eternal.’

Then the guard had thrown a sack over her head. The halter was drawn still tighter, strangling her, cutting into her neck. Again the pressure on the small of her back was brutal as she was forced forward onto the platform. And then the floor gave way underneath her, and she plummeted down, down—

—and woke up.

Blažena sat up with a start, breathing heavily. She was damp with the sweat of fear. It took her the space of several heartbeats for them to slow down, for her to realise that it hadn’t been real – even though it had felt that way. Blažena rubbed her neck where it met her shoulders. She hadn’t been imagining

that part – her shoulders, neck and the muscles across her back ached badly. She massaged them with her palm for a little while. Maybe she’d been sleeping in a funny position, or maybe she’d been slouching too much again.

And the memory that her nightmare had revisited upon her – that too had been real. More times than she could count, that haunted, scrawny, bearded face swam up before her mind’s eye. She still remembered how he’d stumbled on the stairs up to the gallows. Had the last thing he’d ever felt been the pain of slow strangulation? Or, worse – had it been regret, terror, fear of the unknown beyond life? The fear of the law was writ across his face – had the fear of hell been there as well? Blažena found herself wondering about the poor man’s ultimate fate.

She kicked her legs down over the side of her bed and placed her feet on the floor. Could she talk to someone about this? She went over the possibilities.

Her father had returned from the Czech lands today, and Blažena knew better than to disturb him or her mother at all tonight. They would be… busy.

Radko, maybe? Or Hilda? Though the thought of talking with Hilda was tempting, Blažena discounted it as well. She could tell Radko didn’t like her spending too much time with her sister-in-law, though he wouldn’t say why. The two of them had had to take to meeting in semi-secret, often in town by prearrangement. But Hilda too had been a bit distant of late, and she hadn’t seen Bošiško in what seemed like weeks. Hilda was still nursing Bošiško’s baby brother Prokop, so little wonder there.

Her other siblings, perhaps? Blažena had always gotten along well with Vlasta, newlywed to her Avar groom and surprisingly docile about it, but doubted that she would understand. Vlasta was a simple soul, and not much given to asking deep questions. Krásnoroda would be little help too, sadly: little else occupied her attention but what she was going to buy in town with her next allowance. And Slavomíra…! Blažena shot a glare at the snoozing figure on the bed opposite hers. She wasn’t one to entertain grudges, but her youngest sister was a source of constant frustration to her. Blažena had never really wanted a younger sister, having always been the ‘cute’ one, her father’s darling. But lately Slavomíra had taken to holding forth stridently with her opinions, in a way that made Blažena bristle.

What she

really wanted was to talk to Vieročka. Her eldest sister had always been a source of comfort; she had excellent taste, and was sweet and kind – even if she could be a bit flighty on occasion. But she was with Tihomír in far-off Niš visiting with

Ujko Moisei, celebrating the christening of their third child.

Blažena stood up, lit her bedside candle and went out into the hallway. She didn’t turn down toward her parents’ room or her other siblings’, but went down into the main hall toward the kitchen. She checked in her step, though, when she saw in the main hall another candle was already lit, and a slender figure entering from the chapel. It was Hromislav, her father’s bishop – probably just come out from vigil. Blažena remembered that her father had always gone to Vojmil for advice and comfort when he was still alive. This man of the cloth should be no different – and maybe he had some of the answers she sought.

She went softly down the stairs, candle in hand. The last one, however, creaked loudly. The effect on Hromislav was remarkable: he leapt with a start and a shout of alarm, loudly scraping a nearby bench across the floor and very nearly overturning it. The sudden and frantic movement in turn startled Blažena, who let out a soft cry. That caused the cringing Hromislav to pause. The bishop, seeing that the source of his fear was only one of his lord’s dependents, and a female at that, calmed down – though the fact that she’d seen him take such fright irked him.

‘What are you doing out of bed at this hour, child?’ he demanded sourly of Blažena.

‘I couldn’t sleep,’ she replied truthfully. ‘I actually had some questions, maybe you could answer for me.’

‘This is really not—well—I…’ Hromislav fidgeted with his hands, considering. He too knew that Blažena was her father’s favourite, and he wasn’t about to get on her bad side. ‘Oh, alright, fine. One or two quick questions, then it’s back off to bed with you.’

Blažena was a little bit put-out by Hromislav’s condescending tone – she was thirteen, after all, and not a little child anymore. And what’s more, she was a noblewoman by right of birth, and a man of the cloth ought to treat her with that respect! At any rate, she asked:

‘So, the Church teaches that Saint Dismas went to heaven, correct?’

‘That is what the Church tells us, and therefore that is true. The thief repented of his sins upon the Cross before he died.’

‘So what happened to… you know, the other one? The one who didn’t repent?’

‘Gestas? He is in hell,’ Hromislav shrugged lightly.

Blažena shook her head. ‘How can that be fair?’

‘Gestas joined the crowd in mocking Jesus and telling him to save him if he was truly Christ. The punishment for his crimes, however, was just. And by rebelling against both the law of this world and the King of the next, he sealed his fate eternally.’

‘But,’ Blažena furrowed her brow, again seeing before her mind’s eye the tormented face of another thief who had not repented, ‘what if he had been starving? What if he had a family? What if he had no choice but to steal in order to save the ones he loved? What if he went to his death in terror of what would happen to them? What if he was simply a poor, frightened man who had done the only thing he could do, only to be crushed under the weight of an unjust law?’

Hromislav began to grow irritated. ‘There is no profit in “what ifs”, child. The Church teaches what it teaches. The law of man receives God’s blessing, and there is no bargaining with Him.

Know ye not that the unrighteous shall not inherit the kingdom? Be not deceived: neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor effeminate, nor abusers of themselves with mankind, nor thieves, nor covetous, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor extortioners, shall inherit the kingdom of God.’

Now, had Bishop Vojmil been alive, he might have been able to empathise with the poor girl’s fears, he would have been able to discern that it was not in fact the impenitent thief but some other man who concerned her, and he would have calmly assured her of what the Orthodox Church in fact does teach. We simply

do not know the fate of any person upon his death, and at any rate it is not up to us lowly mortals to decide. And the Judge we must appeal to is

not a vengeful hater, but a lover of mankind. He might have reminded her of the saying of Christ that the Heavenly Father does not give stones to his children when they are hungry but bread, and does not give adders to his children but fish. Or the parables of Christ in which those who ask mercy are given it, in which it is the lost silver coin that preoccupies the woman, or the lost lamb which preoccupies the shepherd.

But it was Blažena’s ill luck that she had come across this particular bishop. Hromislav belonged to a type sadly not uncommon in the medieval Orthodox Church, which was as often as not merely a bureaucratic appendage of the whims of the Emperor in the East. Merely a chaplain to a

doux, a craven and servile petty clerk, Hromislav saw himself not as a shepherd of souls but as a servant to the legitimacy of the rightful earthly ruler.

Upon hearing this answer, Blažena straightened her back and stiffened her sore shoulders as her face blanched with anger. The thought of the thief she’d seen hanged in Salzburg, suffering eternally for his one moment of perfectly understandable hesitation and fear, not only saddened and frightened her. Now it

repulsed her. It was hideous to think of. For the first time in her life, she felt a surge of raw anger and resentment against God, that He would create a man only to condemn him to a life of suffering, to demand of him meek and slavish obedience to his lot, and at the end if he failed to do so to send him into a torment endless in scope and duration, without any chance of reprieve or deliverance.

‘Thank you,’ Blažena told the cleric icily. ‘You’ve been a great help.’

And then she turned on her heel, not waiting for Hromislav to reply, and marched straight back up the stairs.

To make matters even worse, when she got back to her room, she found Slavomíra already awake and alert, sitting up in the bed. As Blažena put the candle on her table, her younger sister reproached her:

‘You shouldn’t even be asking such questions, Blažka. It’s not right for layfolk, let alone those of us of the weaker sex, to doubt the teachings of the Holy Church.’

Blažena was in no mood to humour her sister. ‘Amazing. All those sins the Church preaches to us to avoid – and

eavesdropping isn’t among them?’

Blažena could feel Slavomíra bristle behind her at the rebuke, but she didn’t care.

‘I’m sorry, sister. I’m only concerned for your soul.’

‘You’d best keep your own arse clean, then, and leave me well alone,’ Blažena snapped. She stalked back to her bed and lay down on it, deliberately turning her back on Slavomíra and wrapping herself in her sheet. She did not go back to sleep for a long time after that: resentful of the world’s injustice, and outraged by the indifference of even the court of Heaven to the plight of the lowly, vulnerable, fallible and merely-human.