THE LIONS OF OLOMOUC

a CKIII Ironman AAR

Duchy of Moravia, 867

BOOK ONE. East and West

PROLOGUE

A Debate in the King’s Courtyard

Early Autumn, 866

Icon of Saints Cyril and Methodius, Apostles to Moravia

a CKIII Ironman AAR

Duchy of Moravia, 867

BOOK ONE. East and West

PROLOGUE

A Debate in the King’s Courtyard

Early Autumn, 866

Icon of Saints Cyril and Methodius, Apostles to Moravia

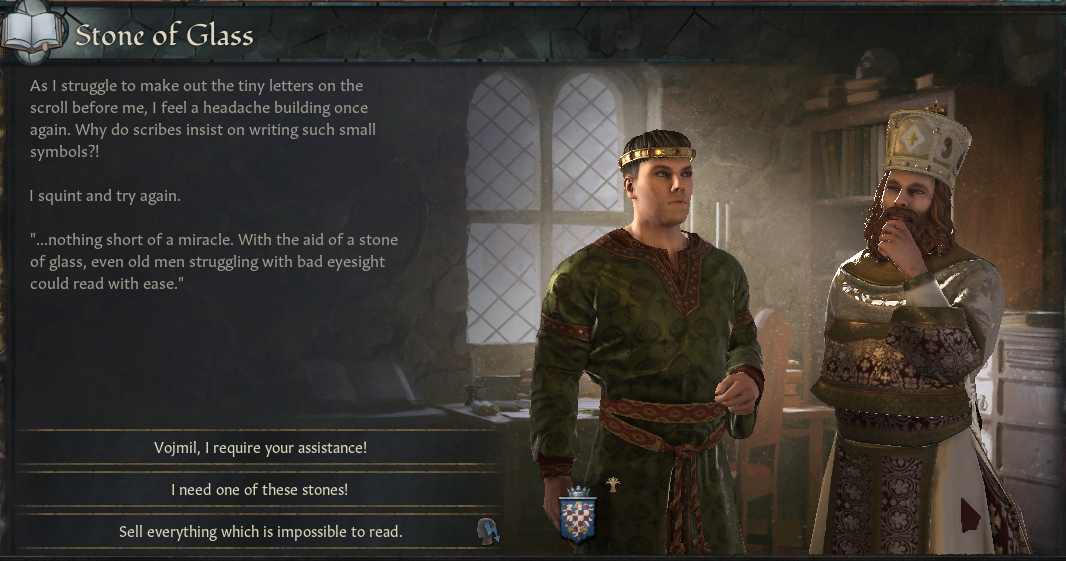

Midday was coming, and the sun was steadily climbing the firmament, filtering down in spotted rays through the forested sky overhead. Although through the dark, gnarled branches of oak and the smoother, lighter branches of hornbeam no trace of human habitation could be seen, the whiff of wood smoke mixed with the more rancid airs of tannery and butchery in his nose, and the distant barking of dogs in his ears, were the first hints to Bohodar that they were nearing a city. And that city would be Velehrad.

Bohodar Rychnovský was part of a lengthy procession that wound its way through the woods of central Morava towards the king’s court. With an easy touch of a gauntleted hand and a gentle call to his mount, he slowed her to a canter and brought himself solicitously back beside the archdeacon’s mule. With worry, he looked toward the elder man’s face. The archdeacon’s long jet-black beard, now streaked with iron grey, folded and perched upon his spare chest as the holy man continued to be lost in thought.

‘Your Grace,’ Bohodar ventured. ‘Are you well enough? Should we rest?’

The archbishop glanced up at Bohodar sideways, with one dark brown eye. Bohodar always felt a little uneasy around the archdeacon. That wasn’t his fault, though. The archdeacon was humility, sweetness and kindness personified toward everyone he met. But although that put most people at ease, it gave Bohodar some misgivings. He always felt like the archdeacon – the man who had taught him to write not only in Greek, but also in his own language with an alphabet he and his ‘baby brother’, Father Constantine, had conjured for the purpose – knew a little too much, could open him up and read him like a book if he so chose… and that perturbed the young knieža of Olomouc. The archdeacon favoured him with a slow half-smile.

‘I am well, praise God,’ he said meekly. ‘As for rest, I can do without. We are close enough now. Please, do not worry so much about me, lad. The old monk Methodius has plenty of miles in him left.’

Bohodar nodded his head and fell silent, but he kept his horse at a canter alongside the archbishop’s, as the deacons bore their banners and swung their gilt smoking censers before him. Bohodar stifled a chuckle as he noticed the rotund subdeacon Vojmil among them, his bushy red beard hiding an ample double chin, bearing his massive paunch proudly and belting out from the Psalter as he held an icon aloft. The knieža felt as though Archdeacon Methodius bore with all the pomp and glitter with a kind of studied stoicism. He used it, celebrated it, understood its value. Methodius never denigrated or sneered at anything beautiful. But for himself, he wore plain black, and his only ornamentations were a pectoral cross and an icon of the Holy Mother of God – both made of wood, not gold or gilt metal. At times like these, Bohodar half-wished that Methodius, his teacher and mentor, would avail himself more directly of some of these showier trappings, straighten his spine and jut out his chin a bit. But that was never his way. Methodius chose to sway instead through humility and self-denial. Bohodar understood this, admired it, and was at the same time a bit exasperated by it.

The young nobleman was convinced – indeed, his own learning was proof – that this mission that Methodius and his brother Constantine were on was righteous and noble, and blessed by God. If Christ wanted to call the Slavs to him, why could He not do it in their own language? Why did these nemeckí priests and bishops insist that they must come to preach to the Slavs in Latin? It made much more sense to him, seemed much more just, that God could speak to the heart in whatever language that heart spoke. Methodius never showed any effrontery on his own behalf, and indeed he went meekly where he was called. But Bohodar felt it in spades for him. Thinking thus, he was riding tall and stern in his saddle as they came within view of the main gate to Velehrad – the holy man’s sworn paladin ready to defend him against all who might come against him, whether Frank or Italian.

And now Rastislav King of all Morava had summoned the kindly archdeacon to him – and the message that he had sent with his seal of authority had been of dire import. He had been called to answer a council of bishops that had gathered in Velehrad. The messenger had not said anything about which bishops had come, only that they had charged him with heresy, ecclesiastical trespass and fomenting schism. There was no way he could not come in person to answer these charges.

Seeing the procession afar off amidst the trees, with its gilt-fringed banners held high, censers swinging, and psalms for protection and intercession wafting up in harmony, the watchmen readily swung open the heavy timbered gate that led inside the long wooden stockade that surrounded Velehrad. The familiar sights and smells of the city met Bohodar at once. The smoke of wood fires and hearths mingled with the scents of slaughtered and curing meat, the sweet warmth of baking bread, and the sharper tangs of tanning hides, offal and excrement both human and animal. Chickens clucked and dogs barked from beneath the overhangs of steep-roofed rough-timbered zemnicy. Children clad in undergowns – or in nothing at all, the late autumn still being fairly warm – women in their aprons and men with their caps and tunics, all turned out to see this procession make its way into the city. Some folk crossed themselves piously as the censers, holy books and banners went past with their bearers. Some even chanted along with the psalms, remembered or half-remembered. Others muttered and spat.

Methodius kept riding forward in humility. He did not keep distant from those who came to him, but made the sign of the cross with his hand and gave blessings to those who came forward to ask. Children who came up to him received a warm smile beneath the black-and-iron beard and a kindly pat on the head or a playful swat, as they seemed willing to receive. One thing had to be said for Methodius’s way of doing things – it was rather infectious. Bohodar already had his purse out, and was giving pieces of silver to beggars and orphans along the road.

As the High Hall of Rastislav, king of Morava, hove into view, a sombre mood fell over the procession. The Frankish bishops had already arrived with their retinues. Their mitres were perched lofitly as they looked upon Methodius’s procession with ill-concealed hostility. Bohodar scanned the retinues and tried to place them – if not by their faces, then by the devices of their attendants. One level white brow and hard mouth under a silvery beard made themselves known to him at once. They belonged to the Moravians’ neighbour to the southwest, Archbishop Adalwin of Salzburg – who had been claiming jurisdiction here for years. Lower than him was a slightly younger man, fair-avised and with a kindlier face. Though he didn’t know him to look at, Bohodar knew him by the shields of his retinue: he was the suffragan of Augsburg, and his name was Rizzo. And the third and least prestigious bishop’s device he didn’t know at all: it was a party per pale sable and argent.

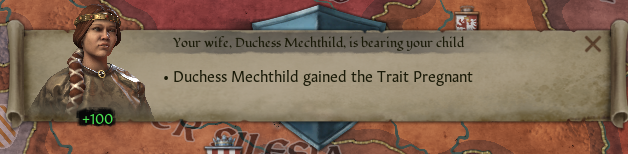

Moving in the throng with the grace and poise of a hind in woodlands, someone in the last bishop’s party caught Bohodar’s eye as they went past. It was held by the great heavy braid over her shoulder, gleaming with fine chestnut polish. The nemka’s head quirked as she sensed the Slovien lordling’s intense regard. Knowing she was watched, her dark heavy-lidded eyes lifted suddenly with a fetching sparkle. The beauty-mark under her left cheek twitched upward as her rose-petal lips curved into a puckish smile. Bohodar shook his head quickly and wrenched his gaze away from her… but even as they went by, his organs of sight of their own will kept going sidelong towards her.

The riders in the procession dismounted and handed their animals off to the stable-boys who came to fetch them. Meekly and without a word, Methodius took up the final place among the clerics assembled there, and the Sloviens in procession were the last inside. That suited the Frankish bishops – they had evidently been kept waiting long enough as it was. Bohodar also made no word of complaint, as the heavy chestnut braid belonging to the fetching nemka swayed with her graceful step not two paces in front of him as they entered the hall.

It took the space of a few breaths for Bohodar’s eyes to adjust to the flickering torchlight inside the hall, coming in as they did from the brightness of outside. The long, steep-raftered, smoky hall would have been inviting, though, if it weren’t for the grim errand they were currently on. Behind the middle hearth – now unlit and cold, for it was not yet needed – Rastislav King of Morava stood from his high seat to greet the inbound clerics. Adalwin made a fairly stiff and reluctant obeisance, followed by Rizzo’s more suave one. When it came to Methodius, the deacon merely placed a hand over his heart and gave a gentle bow – it could have been a greeting to a king, or it could have been a monk bowing in passing to another. Rastislav gripped the deacon in a warm hug before he took his seat, but made no other show of affection. Bohodar as well came before his liege and kinsman, knelt and kissed his ring, before he took a seat among his party.

‘I bid you welcome, you who hold the keys to bind and loose in heaven,’ Rastislav intoned through his hoary beard. ‘I am most pleased that you could all come together here in amity and brotherhood, as befits the servants of Christ.’

Bohodar shot a sharp look at his king. There was little of Christian amity and brotherhood here at the moment… indeed, Bohodar could feel the chill, haughty hostility of the Frankish bishops toward this elderly deacon. But the face of his liege was bland and benign. If there was any admonishment in his greeting, he had kept it well-hidden beneath a plausible veil of affability and goodwill. Rastislav was a man of many moods. Bohodar recognised – and valued – in his liege the gracious open-handedness and genuine beneficence that had caused so many of the Slavic lands to flock to him. But he also knew well enough that Rastislav was equally generous in his rage and not a man to be crossed, even by his own close kin. It had been only two years before that his king had been captured by Ludwig the Pious, and forced to swear fealty and surrender hostages to the German king – Bohodar among them. But Rastislav had been neither slow nor lenient to avenge, for only last year he had gone on campaign and wrought blood and fire across the Danube.

‘I wish us all to remember this well in light of the weighty matter which brings us here,’ Rastislav went on, his voice still placid, ‘and judge not in haste, but with true judgement.’

‘That is well said, Your Grace,’ Archbishop Adalwin spoke up. ‘And I hope it is with true judgement that we can clearly acknowledge here the great injury that has been done to the body of Christ. It should be a matter of great shame for us all, that we have allowed this petty wrangling and bickering to occlude from our sight the demands of His truth.’

Bohodar ground his teeth. And who is it that has been doing the wrangling and bickering? he thought.

‘The first of Christ’s apostles in this territory were, as Your Grace understands well enough, representatives of the Diocæses of Passau and Salzburg. We obtained, and were granted, licence both by the Holy Father in Rome – and by the worldly authority of the Emperor. This is not a self-interested plea on our part. We have the best interests of the Slavic flock foremost in our minds and in our prayers. Being as yet young and inexperienced in the faith, the Slavs require a firm shepherding hand. And that hand must be guided by a magisterial authority which is singular and unquestioned. This man—’ here Adalwin levelled a long index finger from one draping sleeve toward Methodius, ‘—this man has, with disregard for proper Church discipline, with brazen contempt for the honour of the Holy Father’s ecclesiastical authority, with total disdain even for common courtesy and hospitality, undertaken upon dubious authority to hold unsanctioned Mass in profane language, and to teach his spurious doctrines in a jurisdiction which is not his. In so doing, he has undertaken to betray Our Lord again, to split His very body. I plead with Your Grace and with my fellow bishops here to see justice done. Have this man removed from your territory, and the rightful bishops and priests restored without question to their prior appointments!’

‘And the three of you who have come here,’ Rastislav spoke calmly to Adalwin, ‘you are all united in your resolve to see Methodius removed?’

‘We are indeed, Your Grace,’ Adalwin jutted out his silver-bearded chin. ‘My brethren in Christ, Rizzo of Augsburg and Adalwald of Grisons, have come with me to your honourable court to support me in the right, and to see justice done.’

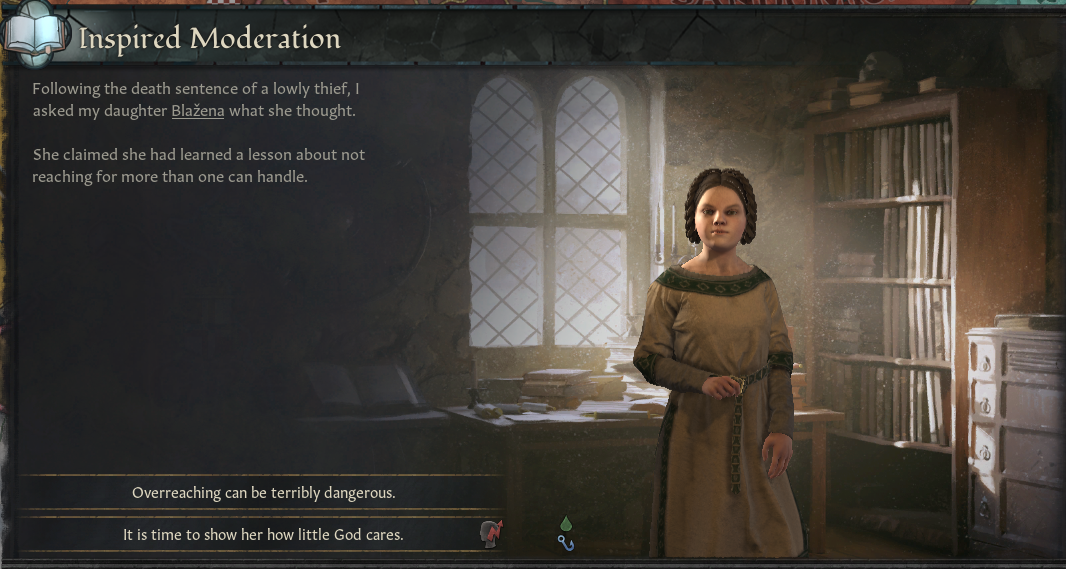

This was too much for Bohodar, who leapt to his feet. ‘You speak of the sanctity of jurisdiction, Your Eminence,’ he began hotly, ‘yet you bring these men from afar off to the west, who have jurisdictions of their own to mind, to press your claim here, like some pettifogging clerk before a town magistrate? In God’s name, are you not afraid to overshoot your mark? Let them return to Augsburg and Grisons, where they may better tend their own flocks! And let those who are called to serve here, serve here.’

Methodius had turned and motioned for Bohodar to sit down and be still, but it was already too late. Having been set on the scent of an injustice needing to be righted like a raw hound pup, Bohodar Rychnovský would not be easily dissuaded from it. The holy deacon rubbed his temples in dismay at the brashness of youth, and began murmuring a fervent prayer to God upon his breath. And now here was the Prince-Bishop of Salzburg, a high governor among the lords spiritual and a mighty Frankish nobleman in his own right, being challenged out of turn in a royal court by a half-heathen twenty-year-old Slovien. Some in the court began to cower from the gathering storm upon the Prince-Bishop’s dread brow. However, others among the Slavs gathered in the hall began to nod and murmur their approval of this lad who had stood up and spoken a fair point of good sense.

‘Take care, boy,’ Adalwin answered Bohodar, ‘for you put your soul in grave peril in your sinful presumption. Do you truly think the man you defend has come here to serve out of holy disinterest? Do you not realise the evil that he represents? Have you no knowledge of the wicked plots and court intrigues this man’s party has undertaken?’

Methodius did not answer this, but continued to pray silently. Bohodar glowered. Adalwin, with a theatrical sweep of his sleeve, went on:

‘Your Grace, although it pains me to speak ill of any man of holy discipline, I feel it is important that you be acquainted with the facts of the case. This Methodius was, and remains, a pupil and a close confidant of the reprobate false bishop and usurper Photius in Constantinople. The grievous crimes that Photius has committed against Christ’s church are threefold. First: he was rushed with no pretence at decency through his ordination. Second: he was ordained by the defrocked Bishop of Syracuse. And third: he was appointed to a see which was already held lawfully by another – the rightful Patriarch Ignatius. And now this Methodius – tutored well in the arts of dissension and schism by his devilish master – seeks to spread the same disorders and confusion here in your territory, by appropriating to himself the authority which rightfully belongs to better men.’

‘I cannot pretend,’ Bohodar answered in an insouciant tone that edged into sarcasm, ‘to be as well versed in the subtle plots and manoeuvres of faraway courts as Your Eminence. I can’t answer for this Photius. But what authority has Methodius usurped? He came to these lands a deacon. He has remained a deacon as long as he stayed here. When has he ever wrangled after such titles and honours?’

‘That’s enough, Bohodar,’ Methodius urged him. His voice was quiet but commanding. But Adalwin was quick to the punch. He gave Bohodar a condescending smile.

‘Alas, poor naïve boy! Do you truly not know how such upheavals and chaos begin? The worst of heresiarchs always come in the plausible sheep’s clothing of humility and meekness, the better to insinuate themselves among the flock. They approach with soothing words and sweet reason first, the better to lull men of goodwill before they bare their teeth.’

‘In that case – you say you have our best interests in your minds and in your prayers,’ Bohodar pressed on. ‘I take you at your word that you wish to guard us from error and false teaching. Why not, then, welcome a teaching of the true precepts of Christ our God, in a tongue that even the unlearned and unlettered can hear and understand? When the disciple that Jesus loved tried to stop a man casting out devils in His name, did not Our Lord Himself tell him, “Whoever is not against you is for you”?’

Adalwin was indeed angry, but he was far too jealous of his own dignity to stoop to continue arguing with this hothead. He also had a far better read of the room than the youth did. And so he turned instead to the King, spreading his hands wide in a calculated gesture of humble supplication. ‘Your Grace, do you not see my point? Observe, when the teaching authority of the Church is divided and undermined, how easy it is for confusion to quicken and spread! I appeal to you – for the sake of your own authority – put a stop to it before it blossoms into rank heresy.’

Rastislav cast a fearsome glower at Bohodar. ‘The Prince-Bishop has the right here, Bohodar. Though you are kin, do not trespass too lightly on my sufferance. While the lords spiritual are holding discourse, it would be best for your health—not to mention your soul—to hold your tongue behind your teeth.’

Bohodar’s eyes blazed, and for one awful moment, Methodius was afraid the young man would incur upon himself the wrath he was tempting. But at last he obeyed his better sense. The blaze passed, and he gave a slow nod to the king, and sat back in his seat. There was an expression something like a slight smirk on Adalwin’s face as he continued his harangue against Methodius that made the deacon’s young noble acolyte fume the more. But he obeyed the command laid upon him by the king without complaint for the remainder of the session, until the king retired. After that, Bohodar was among the first in the hall to stand, stride to the door and burst out into the open courtyard.

‘Antsculdigi,’ came a light voice behind him.

Bohodar turned, and he found himself face-to-face with the disarming young woman of the long, lustrous chestnut braid whom he had noted on the ride into Velehrad. Bohodar guessed she was his senior by perhaps four or five years, yet she was all the more striking for standing so near before him. Her strong cheekbones and slightly snub nose would not be to every man’s liking, but Bohodar found them endearing – all the more so for a pair of lively zibeline eyes which glimmered with intense passion. But just now they were turned upon him seriously.

‘Did you mean all of the things you just said?’ she spoke in an Alemannic lilt. ‘About our bishops? And about the Slavs’ need for Slavic teachers?’

‘Every word,’ Bohodar answered her stoutly.

Those glittering dark eyes widened. ‘Truly? So then, you do not acknowledge the prior rights of the men who risked life and freedom to preach to you the word of life? Who healed your sick and helped your poor, who brought you the Gospel? What indeed of the claims of hospitality?’

Bohodar frowned – not in displeasure, but in serious consideration. ‘I am grateful indeed to Reginheri of blessed memory – the Frankish bishop who sent the first priests among us. He’s the one who baptised my parents, and we have never ceased to commemorate him at prayer. But we Slavs are not yet firm in the faith. We need guides who know our speech, who understand us. The Frankish bishops today should be tutoring students and ordaining priests here, not continuing to send them to us from afar.’

‘But does not the very newness of the faith in these lands argue,’ replied the German girl, ‘that the Slavs are not yet ready to receive such tutelage? Is not some time needed before local priests can be appointed? I am sure that that will come in time.’

‘Under Adalwin’s tender care, I’m sure,’ Bohodar scoffed. ‘You heard him in there. His mind is all on power struggles and court politics. What does he care for the tiller of the soil or the milker of the cows?’

The German girl bridled, lifting her chin belligerently. She replied hotly: ‘That is his office, and it is his by unquestioned right. If he is jealous for the honour of the Church among the princes of the world, can he be blamed for it? Would you have all bishops be obsequious and spineless, shifting with the winds as they blow? Bishop Adalwin has it right. Maybe what you are seeking is not truth, but disorder.’

Bohodar was about to make his own angry retort, when a hoarse voice called out across the yard of the king’s hall.

‘Mechthild!’ cried the exasperated elderly Adalwald, the bishop of Grisons, in whose retinue the girl belonged. ‘For shame! Do not speak so familiarly to a man you don’t know!’

Mechthild – now Bohodar had a name to match the striking face – turned a thought toward Adalwald, bit back something that may have been defiance, gave Bohodar one last aggrieved glance, turned her braided head and strode off. Bohodar was left incensed as he looked out after her. He was still breathing heavily when Deacon Methodius approached him, having been loosed for the moment from his obligations within the hall. The holy monk had seen and heard the entire exchange.

‘Can you believe that infuriating female?!’ Bohodar fumed. ‘Who does she think she is?’

Methodius regarded his young pupil placidly before answering his question with a wry smile. ‘A loyal daughter of the Church… and someone who strives after justice. Remind you of anyone you know?’

Bohodar began a chuckle, but again he had that unnerving feeling that Methodius was seeing straight through him – reading him like an open book. And he didn’t like one bit the implication that the holy monk was making. ‘What? You think she’s like me? That nemka?’

‘We are all children of the Most High,’ Methodius told him. ‘German, Slav, Greek, African, even Saracen. All of us are made in the image and likeness of Christ. Though you may look different and speak different tongues, the two of you are far more alike than you realise. And what’s more…’ here Methodius paused.

‘What?’ asked Bohodar.

Methodius fixed him with a look that was suddenly stern. ‘Be sure you treat that girl with due respect. She might make a fitting wife, but take care not to overstep your bounds in pursuit of her, or place her womanly honour in danger.’

‘What? Wife? Pursuit?’ Bohodar laughed aloud. ‘Is that likely? You saw how she behaved just now.’

Methodius made no reply, but leaned forward toward the young Slovien lord and tapped the side of his nose. Bohodar Rychnovský found himself at a loss for words once again. The benign, sweet elderly monk seemed to see within him, seemed to understand the stirrings of his heart even before he felt them. Clearing his throat, Bohodar made an attempt to change the subject.

‘And what of you, Father Deacon? Tell me they didn’t defrock you. Or expel you!’

‘God be thanked, no,’ Methodius answered him. ‘Rastislav still remembers well and with gratitude when he sent for me and my little brother from the City. He wouldn’t so lightly cast me off. But Constantine and I do need, I think, to make a little pilgrimage to the Holy Father in Rome, and soon – if indeed for no other purpose than to clear the air around these questions of jurisdiction in Morava. I have no wish to be at odds with any in Christ’s Church, not even with Adalwin.’

Bohodar nodded understandingly, but he still feared for his teacher. Who could know what the Holy Father in Rome might tell him, or how he might rule? Even if Rastislav had not cast him out, the penalties from the chief see in the Vatican might be equally if not more dire.

‘Do not worry so much,’ Methodius patted Bohodar on the shoulder. ‘I will not leave my flock alone or friendless here. Gorazd is staying. So are Sava and Angelar. And of course, in Olomouc I will be leaving Vojmil to tend the church while I am away.’

‘Oh, joy,’ Bohodar muttered. The rotund, red-bearded subdeacon was not among his favourite of people. But better to have him than no one at all.

‘And remember what I told you about the other matter,’ Methodius inclined his head toward the clerical party from Grisons across the yard, where Mechthild still was. ‘God bless you.’

Last edited:

- 9

- 1