Kurt_Steiner: A bouncing Betty...thanks to anime, my mind is so going in the wrong direction right now.

SirNolan: Isn’t “honest graft” an oxymoron?

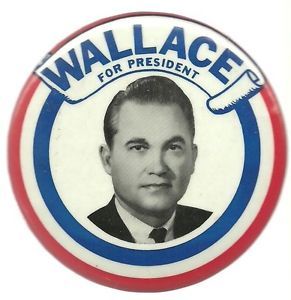

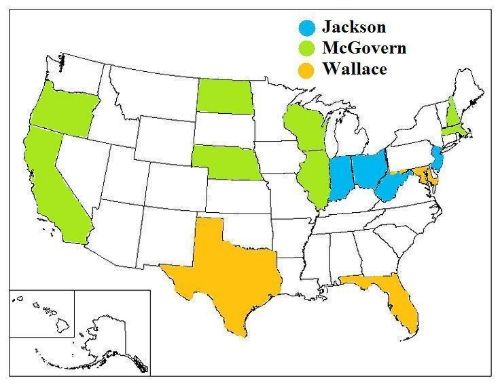

Of course this is McGovern we’re talking about. He isn’t exactly known for his running mate-picking skills.

Hey! I give you two elections for the price of one! Talk about a deal!

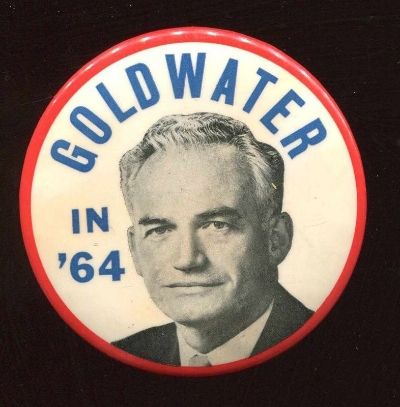

I have a few ideas what the Republicans could do after 1964.

I wonder if Reagan could still make it to the White House in the absence of a Goldwater nomination in 1964.

Kaiser Chris: Johnson was certainly a much better President when it came to civil rights than Kennedy, who had to be pushed into doing even the bare minimum for civil rights. I doubt we would have gotten the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had JFK not been assassinated.

You’re certainly right about Medicare being a discussion for another administration in this AAR. The conservative Republicans in Congress are in no mood to create another welfare program, as Scoop has learned the hard way.

I read a biography about Goldwater by Lee Edwards which touched briefly on how President Goldwater might have handled the Vietnam War. Edwards thinks Goldwater might have escalated the air war instead of relying on conventional ground troops.

That reminds me of something someone said once. “John F. Kennedy proved he couldn’t be prevented from becoming President simply because he was a Roman Catholic. Richard Nixon proved he couldn’t be prevented from becoming President simply because he was Richard Nixon.”

To answer your question about Johnson's shady political practices, the answer is “Yes.” Johnson did indeed earn a substantial fortune through shady means and indeed there was the beginning of a Congressional investigation into Johnson's dealings in late 1963. Jeff Greenfield wrote an alternate history novel called “If Kennedy Lived” imagining a 1960s where JFK lived to serve two full terms. One of the chapters in his book shows the Congressional and “Life” investigations continuing and LBJ being forced to resign because of the resulting revelations. Greenfield’s chapter was a big influence on how I imagined the continuation of those investigations into the Vice President for my story.

Donald Trump reminds me of a campaign slogan that appeared after Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952: “I don’t like Ike yet but I’m working on it.”

I don’t know what Polandball comics are.

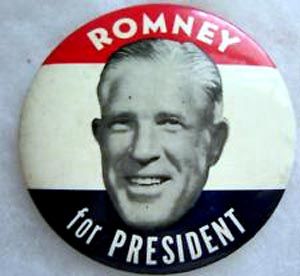

jeeshadow: So you would like Romney to be President, eh?

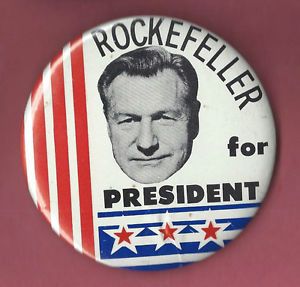

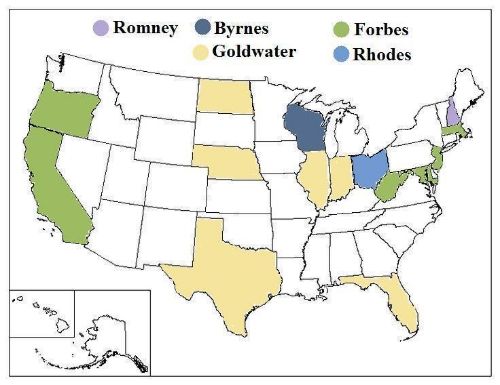

Kaiser Chris: With Malcolm Forbes, I can easily see the economy being his bread-and-butter issue as a successful politician.

As for Goldwater, it isn’t that he is more moderate on the issue of civil rights TTL. It’s that he believed the Federal Government had a constitutional obligation to enforce voting rights. He was absent from Congress during the Voting Rights Act of 1965, so he never got to cast a vote for it. Given his record of voting for other civil rights bills that dealt primarily with voting rights, I think he would have voted for it.

Given how badly divided the Republicans were in the 1950s, I think Forbes would very much want to bring Goldwater on board his campaign. Given that Goldwater was a Good Republican who supported everyone regardless of their views, I think he would get behind Forbes.

Wow! You remember the long-since abandoned timeline in the original Presidents AAR. That surprises me for some reason.

El Pip: I’m glad you have caught up with my AAR, El Pip.

The Domino Theory is what is driving American involvement in South Vietnam. If the country falls, Cambodia would follow quickly and the Chinese would be knocking on Thailand’s door.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Che Kung Riot

In the midst of the political drama that would lead to the resignation of Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, President Henry M. Jackson hosted President Diosdado Macapagal of the Philippines at the White House on January 12th, 1964. Macapagal was paying a state visit to the United States, with whom his country enjoyed a very close relationship. In the Oval Office, the Philippine President sat down with the American President to discuss a pressing issue: China. Like other nations in Asia, the Philippines were watching China’s saber-rattling with increasing alarm. Although the island nation didn’t face a direct threat from this growing power the way Korea and the nations of Southeast Asia were, she did face an indirect threat. China’s decision to conduct routine naval patrols in the Western Pacific worried Manila, who felt that the Republic of China Navy posed a serious threat to her access to sea lanes – especially in the South China Sea, where ROC ships were roaming the sea at will. As his country’s most important ally, Macapagal asked America for help in defending his country’s free navigation of the sea from Chinese encroachment. Jackson responded to the request by ordering the United States Navy to establish routine naval patrols in the South China Sea. The purpose of these patrols would be to keep open the sea lanes in the South China Sea, thereby preventing the ROCN from being able to close them off to other nations at whim. The Chinese didn’t take kindly to what they perceived as America’s meddling in their waters. Nanjing regarded the presence of US ships in the South China Sea as being a provocation and vaguely warned of “consequences” should the USN provoke the ROCN into taking defensive action.

(The Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer USS Maddox, seen here on patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964)

China’s decision to conduct routine naval patrols in the Western Pacific was an effort to project her naval power for everyone to see. In the mid-1960s, China wanted to show the world that she was no longer this weak and impotent country that others could kick around at will and exploit for their own gain but a strong power that deserved to be respected and be taken seriously by others. Chiang Kai-shek had a vision of China being the postwar leader of Asia and he was getting more aggressive in turning that vision into a reality. To unite Asia under China’s leadership and guide the continent into a prosperous future, it was deemed necessary by Chiang to expel from the continent the presence of the West which was standing in the way of a true “Asia for Asians”. One obvious bastion of the West in Asia that had to be removed was the British colony of Hong Kong. The island, which sat off the southern coast of China, had become a source of considerable tension between Nanjing and London. Claiming Hong Kong to be rightful Chinese territory, Nanjing in 1961 unilaterally nullified the treaties giving the British control of the city and demanded that the British withdraw at once. London responded by rejecting the territorial demand and beefing up her military presence in Hong Kong. Prime Minister Rab Butler, knowing that his Premiership was riding on his taking a firm stand against China, reiterated both publicly and privately that Hong Kong belonged to his country and his country alone. The British dug in, refusing to go anywhere.

(The Centaur-class light aircraft carrier HMS Centaur, stationed in Hong Kong in 1964 as part of the naval force defending the colony)

With the British throwing up stubborn resistance, Chiang looked for other ways to exert pressure on London. The patrols by the ROCN which worried the Philippines were partly an attempt by the Chinese government to render the British position untenable by stressing the fact that Hong Kong was surrounded by China both geographically and militarily and could be easily cut off from the outside world. Chiang also ordered the National Security Bureau, China’s principal intelligence agency, to covertly stir up trouble in Hong Kong. One of the things they tried was to fund partisans who would create trouble for the British authorities. While there were Chinese citizens living in Hong Kong who were content with life under British rule (the living standard in Hong Kong was rising steadily but wages continued to be low), there was an underground movement of Hongkongers who favored unification with the Chinese mainland. These pro-unification partisans were cultivated and supported by the NSB, who viewed them as being the natural conduit in which to create internal dissent. With aide flowing in from the NSB, the partisans began putting together a plan to confront the British authorities with a major pro-unification demonstration that would hopefully be seen by the world as proof that the Chinese population in Hong Kong were chafing under British colonial rule and that they badly wanted to unite with their brothers on the mainland. The demonstrators were counting on the Hong Kong Police Force to react forcefully, thereby making them look like martyrs in the name of freedom and self-determination for colonial people. In early 1964, they were ready to act...and they had an easy way to let everyone know what they were advocating.

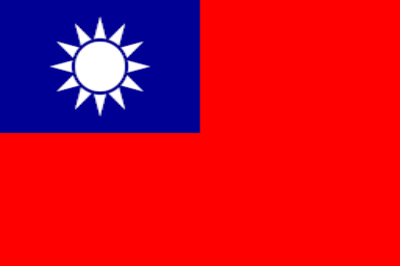

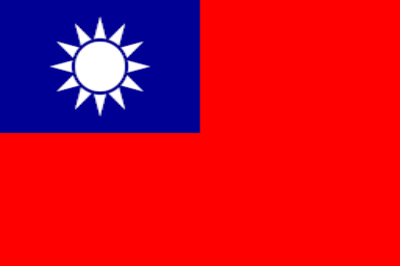

“Blue Sky, White Sun, and a Wholly Red Earth” is the official name of the national flag of the Republic of China. Originally designed by Lu Haodong in 1895 and modified by Sun Yat-sen in 1906, “Blue Sky, White Sun, and a Wholly Red Earth” became the official national flag on December 17th, 1928. The twelve rays of the White Sun in the Blue Sky symbolizes the twelve months of the year and the Wholly Red Earth symbolizes the blood of the revolutionaries shed in overthrowing the Qing Dynasty in 1912 which lead to the establishment of the ROC. Since it is the national flag, it flies all over China from Taipei and Beijing to Shanghai and Chongqing. One place that it wasn’t flying over in the mid-1960s was Hong Kong. In an effort to suppress Chinese nationalism on the island, British officials had banned the display of the Chinese flag. So of course the demonstrators wanted to march through the streets of Hong Kong parading the banned flag, knowing full well that their act of defiance wouldn’t be tolerated by those in charge. For maximum attention, the NSB-backed partisans chose February 14th, 1964 – the second day of the Chinese New Year – to stage their demonstration. Traditionally on the second day people would be in the streets of Hong Kong celebrating the birthday of Che Kung, a local deity known for his great power of protection. With so many people out and about, it seemed like the best time for the demonstrators to get their message across and provoke a reaction by the authorities.

(Che Kung)

On February 14th, the demonstrators took to the streets of Hong Kong. They displayed the Chinese flag in open defiance of the ban, shouted anti-British pro-Chinese rhetoric, and carried banners demanding unification with the mainland. They primarily aimed their political message at the thousands of people who were heading to Che Kung Temples to worship. It didn’t take long for word of the demonstrations to reach the Hong Kong Police Force, who then moved to quell what was obviously a challenge to British authority. What happened next depends on who you ask. According to the official police report, when they confronted the demonstrators and demanded that they cease their unlawful activities at once, they were attacked by thrown stones. The demonstrators of course contend that they were being peaceful and that it was the police who attacked them first without provocation. Regardless of who threw the first punch, there was a violent clash between the demonstrators and the police which quickly escalated into an all-out riot. Over the course of the next five days, violence roiled Hong Kong as pro-unification demonstrators fought battles with the Hong Kong Police Force. The government imposed a curfew in order to get people off the streets and ordered every member of the police force to report for duty. The police, which had a large number of ethnic Chinese serving, were then granted special powers to quell the rioting. After days of intense fighting (some of which took place in the streets and some inside buildings), the partisans were defeated and order in Hong Kong was finally restored on February 19th. At the end of the Che Kung Riot, 26 people were dead, 416 were wounded, and 2,490 demonstrators had been arrested. Scores of buildings had been either damaged or were destroyed during the course of the rioting.

The Che Kung Riot marked a turning point in the battle over Hong Kong. Until then, Nanjing and London had been engaged in a war of words and posturing over the ownership of the island. Now blood had been spilled in the streets, taking the territorial dispute to a new level. China was quick to condemn the violence, criticizing the British for their “brutal repression” of the demonstrators who had been “peacefully” calling for the end of British colonial rule and a return to Chinese sovereignty. Nanjing profusely praised the demonstrators for standing up to the British, who were painted as being all too willing to resort to violence in order to maintain their grip on a place where they clearly weren’t wanted by the public. The British of course saw things differently. The Hong Kong Police Force was praised back in England for quelling the riot and restoring order in the city. Queen Elizabeth II honored the police by granting them a royal charter; they would henceforth be known as the Royal Hong Kong Police Force. The violence however was far from over. The pro-unification partisans retreated back underground and proceeded over the next few years to carry out a campaign of terrorism. There were bombings across Hong Kong and assassinations of officials. In May 1966, Hong Kong Governor David Trench was shot by a would-be assassin but miraculously survived. Given the unrest in Hong Kong during the mid-1960s and the looming threat of war between China and the West, many Hongkongers chose to pack their bags and flee to safer havens overseas.

SirNolan: Isn’t “honest graft” an oxymoron?

Of course this is McGovern we’re talking about. He isn’t exactly known for his running mate-picking skills.

Hey! I give you two elections for the price of one! Talk about a deal!

I have a few ideas what the Republicans could do after 1964.

I wonder if Reagan could still make it to the White House in the absence of a Goldwater nomination in 1964.

Kaiser Chris: Johnson was certainly a much better President when it came to civil rights than Kennedy, who had to be pushed into doing even the bare minimum for civil rights. I doubt we would have gotten the Civil Rights Act of 1964 had JFK not been assassinated.

You’re certainly right about Medicare being a discussion for another administration in this AAR. The conservative Republicans in Congress are in no mood to create another welfare program, as Scoop has learned the hard way.

I read a biography about Goldwater by Lee Edwards which touched briefly on how President Goldwater might have handled the Vietnam War. Edwards thinks Goldwater might have escalated the air war instead of relying on conventional ground troops.

That reminds me of something someone said once. “John F. Kennedy proved he couldn’t be prevented from becoming President simply because he was a Roman Catholic. Richard Nixon proved he couldn’t be prevented from becoming President simply because he was Richard Nixon.”

To answer your question about Johnson's shady political practices, the answer is “Yes.” Johnson did indeed earn a substantial fortune through shady means and indeed there was the beginning of a Congressional investigation into Johnson's dealings in late 1963. Jeff Greenfield wrote an alternate history novel called “If Kennedy Lived” imagining a 1960s where JFK lived to serve two full terms. One of the chapters in his book shows the Congressional and “Life” investigations continuing and LBJ being forced to resign because of the resulting revelations. Greenfield’s chapter was a big influence on how I imagined the continuation of those investigations into the Vice President for my story.

Donald Trump reminds me of a campaign slogan that appeared after Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952: “I don’t like Ike yet but I’m working on it.”

I don’t know what Polandball comics are.

jeeshadow: So you would like Romney to be President, eh?

Kaiser Chris: With Malcolm Forbes, I can easily see the economy being his bread-and-butter issue as a successful politician.

As for Goldwater, it isn’t that he is more moderate on the issue of civil rights TTL. It’s that he believed the Federal Government had a constitutional obligation to enforce voting rights. He was absent from Congress during the Voting Rights Act of 1965, so he never got to cast a vote for it. Given his record of voting for other civil rights bills that dealt primarily with voting rights, I think he would have voted for it.

Given how badly divided the Republicans were in the 1950s, I think Forbes would very much want to bring Goldwater on board his campaign. Given that Goldwater was a Good Republican who supported everyone regardless of their views, I think he would get behind Forbes.

Wow! You remember the long-since abandoned timeline in the original Presidents AAR. That surprises me for some reason.

El Pip: I’m glad you have caught up with my AAR, El Pip.

The Domino Theory is what is driving American involvement in South Vietnam. If the country falls, Cambodia would follow quickly and the Chinese would be knocking on Thailand’s door.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Che Kung Riot

In the midst of the political drama that would lead to the resignation of Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, President Henry M. Jackson hosted President Diosdado Macapagal of the Philippines at the White House on January 12th, 1964. Macapagal was paying a state visit to the United States, with whom his country enjoyed a very close relationship. In the Oval Office, the Philippine President sat down with the American President to discuss a pressing issue: China. Like other nations in Asia, the Philippines were watching China’s saber-rattling with increasing alarm. Although the island nation didn’t face a direct threat from this growing power the way Korea and the nations of Southeast Asia were, she did face an indirect threat. China’s decision to conduct routine naval patrols in the Western Pacific worried Manila, who felt that the Republic of China Navy posed a serious threat to her access to sea lanes – especially in the South China Sea, where ROC ships were roaming the sea at will. As his country’s most important ally, Macapagal asked America for help in defending his country’s free navigation of the sea from Chinese encroachment. Jackson responded to the request by ordering the United States Navy to establish routine naval patrols in the South China Sea. The purpose of these patrols would be to keep open the sea lanes in the South China Sea, thereby preventing the ROCN from being able to close them off to other nations at whim. The Chinese didn’t take kindly to what they perceived as America’s meddling in their waters. Nanjing regarded the presence of US ships in the South China Sea as being a provocation and vaguely warned of “consequences” should the USN provoke the ROCN into taking defensive action.

(The Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer USS Maddox, seen here on patrol in the Gulf of Tonkin in 1964)

China’s decision to conduct routine naval patrols in the Western Pacific was an effort to project her naval power for everyone to see. In the mid-1960s, China wanted to show the world that she was no longer this weak and impotent country that others could kick around at will and exploit for their own gain but a strong power that deserved to be respected and be taken seriously by others. Chiang Kai-shek had a vision of China being the postwar leader of Asia and he was getting more aggressive in turning that vision into a reality. To unite Asia under China’s leadership and guide the continent into a prosperous future, it was deemed necessary by Chiang to expel from the continent the presence of the West which was standing in the way of a true “Asia for Asians”. One obvious bastion of the West in Asia that had to be removed was the British colony of Hong Kong. The island, which sat off the southern coast of China, had become a source of considerable tension between Nanjing and London. Claiming Hong Kong to be rightful Chinese territory, Nanjing in 1961 unilaterally nullified the treaties giving the British control of the city and demanded that the British withdraw at once. London responded by rejecting the territorial demand and beefing up her military presence in Hong Kong. Prime Minister Rab Butler, knowing that his Premiership was riding on his taking a firm stand against China, reiterated both publicly and privately that Hong Kong belonged to his country and his country alone. The British dug in, refusing to go anywhere.

(The Centaur-class light aircraft carrier HMS Centaur, stationed in Hong Kong in 1964 as part of the naval force defending the colony)

With the British throwing up stubborn resistance, Chiang looked for other ways to exert pressure on London. The patrols by the ROCN which worried the Philippines were partly an attempt by the Chinese government to render the British position untenable by stressing the fact that Hong Kong was surrounded by China both geographically and militarily and could be easily cut off from the outside world. Chiang also ordered the National Security Bureau, China’s principal intelligence agency, to covertly stir up trouble in Hong Kong. One of the things they tried was to fund partisans who would create trouble for the British authorities. While there were Chinese citizens living in Hong Kong who were content with life under British rule (the living standard in Hong Kong was rising steadily but wages continued to be low), there was an underground movement of Hongkongers who favored unification with the Chinese mainland. These pro-unification partisans were cultivated and supported by the NSB, who viewed them as being the natural conduit in which to create internal dissent. With aide flowing in from the NSB, the partisans began putting together a plan to confront the British authorities with a major pro-unification demonstration that would hopefully be seen by the world as proof that the Chinese population in Hong Kong were chafing under British colonial rule and that they badly wanted to unite with their brothers on the mainland. The demonstrators were counting on the Hong Kong Police Force to react forcefully, thereby making them look like martyrs in the name of freedom and self-determination for colonial people. In early 1964, they were ready to act...and they had an easy way to let everyone know what they were advocating.

“Blue Sky, White Sun, and a Wholly Red Earth” is the official name of the national flag of the Republic of China. Originally designed by Lu Haodong in 1895 and modified by Sun Yat-sen in 1906, “Blue Sky, White Sun, and a Wholly Red Earth” became the official national flag on December 17th, 1928. The twelve rays of the White Sun in the Blue Sky symbolizes the twelve months of the year and the Wholly Red Earth symbolizes the blood of the revolutionaries shed in overthrowing the Qing Dynasty in 1912 which lead to the establishment of the ROC. Since it is the national flag, it flies all over China from Taipei and Beijing to Shanghai and Chongqing. One place that it wasn’t flying over in the mid-1960s was Hong Kong. In an effort to suppress Chinese nationalism on the island, British officials had banned the display of the Chinese flag. So of course the demonstrators wanted to march through the streets of Hong Kong parading the banned flag, knowing full well that their act of defiance wouldn’t be tolerated by those in charge. For maximum attention, the NSB-backed partisans chose February 14th, 1964 – the second day of the Chinese New Year – to stage their demonstration. Traditionally on the second day people would be in the streets of Hong Kong celebrating the birthday of Che Kung, a local deity known for his great power of protection. With so many people out and about, it seemed like the best time for the demonstrators to get their message across and provoke a reaction by the authorities.

(Che Kung)

On February 14th, the demonstrators took to the streets of Hong Kong. They displayed the Chinese flag in open defiance of the ban, shouted anti-British pro-Chinese rhetoric, and carried banners demanding unification with the mainland. They primarily aimed their political message at the thousands of people who were heading to Che Kung Temples to worship. It didn’t take long for word of the demonstrations to reach the Hong Kong Police Force, who then moved to quell what was obviously a challenge to British authority. What happened next depends on who you ask. According to the official police report, when they confronted the demonstrators and demanded that they cease their unlawful activities at once, they were attacked by thrown stones. The demonstrators of course contend that they were being peaceful and that it was the police who attacked them first without provocation. Regardless of who threw the first punch, there was a violent clash between the demonstrators and the police which quickly escalated into an all-out riot. Over the course of the next five days, violence roiled Hong Kong as pro-unification demonstrators fought battles with the Hong Kong Police Force. The government imposed a curfew in order to get people off the streets and ordered every member of the police force to report for duty. The police, which had a large number of ethnic Chinese serving, were then granted special powers to quell the rioting. After days of intense fighting (some of which took place in the streets and some inside buildings), the partisans were defeated and order in Hong Kong was finally restored on February 19th. At the end of the Che Kung Riot, 26 people were dead, 416 were wounded, and 2,490 demonstrators had been arrested. Scores of buildings had been either damaged or were destroyed during the course of the rioting.

The Che Kung Riot marked a turning point in the battle over Hong Kong. Until then, Nanjing and London had been engaged in a war of words and posturing over the ownership of the island. Now blood had been spilled in the streets, taking the territorial dispute to a new level. China was quick to condemn the violence, criticizing the British for their “brutal repression” of the demonstrators who had been “peacefully” calling for the end of British colonial rule and a return to Chinese sovereignty. Nanjing profusely praised the demonstrators for standing up to the British, who were painted as being all too willing to resort to violence in order to maintain their grip on a place where they clearly weren’t wanted by the public. The British of course saw things differently. The Hong Kong Police Force was praised back in England for quelling the riot and restoring order in the city. Queen Elizabeth II honored the police by granting them a royal charter; they would henceforth be known as the Royal Hong Kong Police Force. The violence however was far from over. The pro-unification partisans retreated back underground and proceeded over the next few years to carry out a campaign of terrorism. There were bombings across Hong Kong and assassinations of officials. In May 1966, Hong Kong Governor David Trench was shot by a would-be assassin but miraculously survived. Given the unrest in Hong Kong during the mid-1960s and the looming threat of war between China and the West, many Hongkongers chose to pack their bags and flee to safer havens overseas.