Jape: Yes. A plunge JFK was historically loathed to take. Unlike Kennedy, Jackson has no reluctance about deepening US involvement in Vietnam because he sincerely believes that the US can win there. Members of his party don't quite share that optimistic view, though.

The answer is "Yes". When LBJ historically made the decision to escalate American involvement in Vietnam in 1965, the opinion polls showed that a majority of Americans supported escalation. It wasn't until Vietnam turned into a never-ending quagmire with undefined victory goals that public support plummeted.

The Chinese position in supporting the Vietcong is one of convenience, not ideology. The government in Nanjing is Paternal Autocrat, with Chiang Kai-shek calling the shots. The Chinese want to get rid of the US-supported regime in South Vietnam and the Vietcong just happen to share the same goal. As for the economic question, the answer is "Yes". Although China TTL isn't Communist and the Chinese people are somewhat better off (they have a television cooking show for instance), they still have to live under the control of a dominating regime.

Thanks. Wait until you see the next update, Jape.

Kurt_Steiner: The question?

H.Appleby: I'm not sure what this question is exactly.

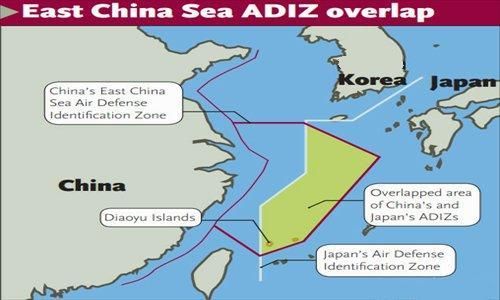

Of course, one should keep in mind that the borders were drawn courtesy of HOI. The odd-looking division of Manchuria between China, Mongolia, and the Soviet Union is the result of those three countries controlling the respective provinces. While Manchuria looks weird, I rather like it because it reinforces just how balkanized China became in my HOI game. And then there's Tibet, free (for now) and enjoying the status of being the Switzerland of Asia.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Vietnam War Begins

In May 1962:

(It was in the 1960s that electronic gaming, today a multi-billion dollar industry, started to take shape)

According to opinion polls taken at the start of May 1962, a majority of the American public supported the President’s decision to deploy troops to the Dominican Republic and South Vietnam. The Gallup Poll put that number at 73 percent. Despite the fact that the country would suffer casualties, many Americans expressed confidence in the President to lead the country through to a victorious conclusion. There was no such thing as a “credibility gap” at the time. If Scoop Jackson said it was necessary to be involved in these two countries, the public was willing to believe him. As one historian has duly noted, “The American people trusted their Presidents to solve the problems of the world.”

Jackson could count on the public to have his back; Congress...not so much. By contrast, the President’s speech received a mixed reaction on Capitol Hill. The reason: Vietnam. Whereas there was general Congressional consensus that troops needed to be sent to the Dominican Republic, the decision to send troops to South Vietnam sharply divided Congress along ideological lines. The resulting debate became a replay of the reaction to the United Nations Speech the previous March. Liberals were openly skeptical of the President’s Vietnam policy. Despite the fact that he said that US involvement in that country came with an exit strategy, liberals openly expressed doubt that US forces could achieve the objective of knocking out the Vietcong. “The French couldn’t win over there,” one Democratic Senator noted, “And the President honestly believes we can do better?”

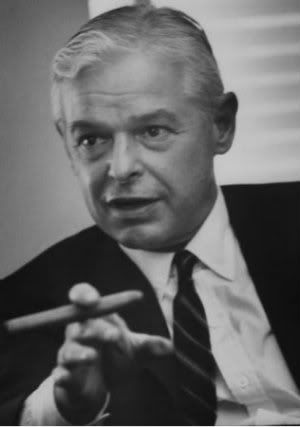

Several top Democrats said their biggest fear was that the US would get badly bogged down trying to fight guerillas in a jungle environment that clearly benefitted the defenders. Appearing on NBC’s “Meet the Press”, Senate Majority Leader Hubert Humphrey was asked about the President’s handling of the Vietnam issue. Humphrey admitted that “the President’s belief that we can settle the problems we are facing [in South Vietnam] with a military solution” gave him “a bad feeling.”

To say that Jackson wasn’t happy with the response he was getting from liberals is an understatement. He had spent weeks on developing this strategy, even tossing and turning in bed at night as the exact number of soldiers to send raced around his mind. It was hard for him to make the final decision, knowing that people would die on his order. Still, he made the call because it was his conviction that South Vietnam was worth fighting for. Now liberals, not having agonized over the decision, were second-guessing the Commander-in-Chief in a knee-jerk fashion and were calling the strategy “unwinnable” before it even had the chance to be implemented. Jackson was deeply indignant...and he showed it. In his speeches educating the American people about the country’s vital stake in Vietnam, the President warned his listeners not to be swayed by what he saw as the Left’s unrealistic view of foreign policy. Though he didn’t mention anyone by name, Scoop criticized liberals in general for not wanting to “bear the burden of a long and difficult struggle. They are impatient for some quick and easy solution to the threats that other nations pose. They want things to be done cheaply and immediately. It is when they cannot get any of this that they become hostile towards doing anything.”

Conservatives on the other hand praised his Vietnam policy as one standing up for America’s interests in Southeast Asia. According to the Right, the United States had to do everything possible to stop the much hated Chinese enemy and that doing anything less amounted to appeasement. In their joint press conference, Republican Congressional leaders Charles Halleck and Everett Dirksen both endorsed Jackson’s use of America’s military muscle to decisively defeat the Chinese drive south. “I agree that obviously we cannot retreat from our position in Vietnam,” Dirksen remarked in his often rambling manner. “It is a difficult situation, to say the least, but we are in and we are going to have to muddle through for a while and see what we do.”

California Senator Richard Nixon, who attacked the Administration whenever possible as part of his strategy of raising his national profile heading into 1964, expressed his support in a back-handed way. The politically opportunistic first-term Senator said that he was glad to see Jackson putting boots on the ground “in order to avoid losing Vietnam like he lost Laos.”

Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, having just published a book laying out a conservative agenda for America, made no bones about what he thought:

“We are at war in Vietnam, and the President – who is Commander-in-Chief of our forces – has gone on the record of saying that the objective over there is victory. The President has drawn the line against aggression, and is being honest with the American people about our full participation. I know he will not allow our finest men to die on battlefields unmarked by purpose.”

During the summer of 1962, while the seasonal joy of having fun at the beach was being reflected by a popular new single from The Beach Boys called “Surfin' Safari”, the President’s Vietnam policy was implemented. As the Americans started moving more of their men and weapons into South Vietnam, they ran into resistance thrown up by Saigon. The South Vietnamese generals who were in charge of the country had been greatly offended by the April 27th speech. They bristled with outrage at the suggestion that they were incapable of defending the country on their own and therefore needed the Americans to come in and turn the place into a US protectorate. “They are refusing to cede too much control,” General Maxwell Taylor cabled Washington on June 23rd. The South Vietnamese generals were trying to look tough, refusing to acknowledge any great need for help by outside forces. Their control of the Vietnamese press allowed them to take their “How dare you suggest we’re weak!” anger out on the American soldiers and newsmen stationed in their country. These complaints in turn irritated the Americans, who felt that the Vietnamese were completely missing the point of their presence. In July, Jackson dispatched Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to Saigon to try to talk sense into the generals as only he could. “You fellows need to understand,” LBJ loudly declared while staring straight into the eyes of the South Vietnamese leadership, “We’re not here to run your country for you! We’re here to stop the Chinese from running your country for you!”

Despite getting The Johnson Treatment, the generals refused to drop their accusations that the Americans were deliberately mischaracterizing them in order to make them look bad and justify their intervention. Evidently they feared the appearance of weakness more than the existential threat being posed by their neighbors to the north. This tension complicated the US mission in South Vietnam while it was still getting off the ground. “How can we defend the country,” Joint Chiefs Chairman David L. McDonald asked rhetorically at a national security meeting held that summer, “If they will not allow us to?”

“We could get rid of them,” Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze said half-jokingly and half-seriously. CIA Director John McCone regretfully shook his head at the suggestion:

“The problem with that, Mr. Secretary, is that there is no one else in Vietnam who could take over. These generals are all we have to go with.”

Scoop sunk into his black leather seat and sighed. At that moment, he wasn’t sure who was worse: his enemy or his ally.

(Among the Americans being deployed to South Vietnam in 1962 was a twenty-five-year-old Army captain from New York City named Colin Powell)

Despite the resistance he was getting from the South Vietnamese generals, the President resolved to “muddle through” and stick with the plan that was currently being put into place. Perhaps once the pressure from the Vietcong had been lifted, the Americans could deal with the stubborn generals on a better footing. For now, Jackson thought, they had to continue pursuing the mission that he had laid out before the nation. As the summer wore on, the pace of deployment quickened. Even before all 40,000 American combat soldiers had arrived (deployment completion was scheduled for the autumn of 1963), Taylor was committing the soldiers he had under his command to limited firefights with the Vietcong. He wanted his men to gain experience now in order to prepare them for the tougher battles that were to come. As helicopters arrived in the country, Taylor immediately sent them out into the field. They were a quick way to move men into and out of the fighting, which was important in South Vietnam’s jungle environment.

In the autumn of 1962, publicity about America’s combat role in Vietnam was everywhere. Across the country, articles about the fighting were appearing in newspapers both large and small. On television, newsmen like Walter Cronkite of CBS were doing segments about the growing conflict on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. With all this domestic publicity, it should come as no surprise that Vietnam became an issue in the November midterm election. Republican candidates generally demanded full military commitment to Vietnam in order to guarantee victory; some on the Right even went as far as to suggest that nuclear war should be risked. If the war against the Vietcong became a losing cause, the Republicans would be ready to blame the President for not having done more. Democratic candidates on the other hand were generally more cautious about getting the country involved in this conflict. Wanting to distance themselves from their hawkish standard-bearer, the Democratic position on Vietnam was more-or-less:

“The Vietnamese need to stand on their own two feet. We cannot and should not do the fighting for them.”

It wasn’t just Democrats who were expressing skepticism at the way Jackson was handling Vietnam. By the middle of October 1962, six months after he had given Taylor the green light, the President was facing questions from reporters over the strategy. With eleven Americans killed in combat missions so far, the press raised concerns about the US military operation in Vietnam. At one press conference, a reporter asked Jackson, “Why should American troops do the bulk of the fighting in Vietnam?”

Jackson answered that it was necessary to fight the guerrillas because the South Vietnamese Army wasn’t strong enough yet to do it by themselves. Then came the follow-up questions. But what about the South Vietnamese leadership? Didn’t they oppose allowing the Americans to take the war to the enemy on their behalf? The President attempted to downplay the generals’ opposition, stating rather weakly that all allies have their differences. “What is important is that we do not allow these differences to distract from our ability to work together in a common purpose.”

The press kept asking questions. With almost 17,500 soldiers stationed in Vietnam by Thanksgiving, was the strategy of having them actively engage the Vietcong a good one? Here the President went out of his way to defend the man behind the strategy. “General Taylor,” he insisted, “Has the confidence of everyone here [in the Administration]. He has demonstrated on numerous occasions that he is a man of sound mind and cool judgment. The reason he is in Vietnam is because he is the best General we have in the Army. You can ask anyone and they will tell you the same thing I told you.”

Scoop reminded everyone that it was Taylor who had commanded the US military mission in Yugoslavia during the 1950s. He credited Taylor’s leadership for helping the Royal Yugoslav Army squash a Communist insurgency that threatened to topple the pro-West royalist regime in Belgrade. The Commander-in-Chief even went as far as to say that “the people of Yugoslavia are enjoying freedom today instead of being trapped behind the Iron Curtain because of General Taylor.”

Although he was stretching things a bit, that claim illustrated Jackson’s confidence that if Taylor could handle the Balkans, he could handle Southeast Asia.

Throughout his Presidency, Henry M. Jackson displayed decisiveness. Once he made a decision to do something, he did it and that was it. He wasn’t someone who second-guessed himself. While decisiveness can be a good trait for a leader, it sometimes got Jackson into trouble. He could be at times too decisive, appearing reckless in his decision-making. That was how liberals felt about him on Vietnam. They felt Jackson was plunging the United States into a war that she didn’t really need to fight; worse, he didn’t seem to care about the human cost that families across the country would have to bear. In the eyes of liberals like South Dakota Senator George McGovern, the leader of the Democratic Party was too hawkish for their comfort. Needless to say, the President didn’t see it that way. When warned by Democratic National Committee Chairman John F. Kennedy in late 1962 that he was “provoking a major furor” within the Democratic Party “over the undeclared war in South Vietnam”, Scoop shot back that it was the fault of the liberals and not his. He stood firm, refusing to back down in the face of liberal criticism. The President displayed his defiance on January 14th, 1963 when he appeared before a joint-session of Congress to deliver the 1963 State of the Union Address. He responded to his opponents by vigorously defending his decision to get the country deeply involved in Vietnam:

“We have sent combat troops there not to conquer but to prevent conquest. We have sent combat troops there not because it is something to do, but because it is the right thing to do. Our brave men are fighting not because they want to fight, but because the forces of tyranny require them to fight for freedom.”

“That was our basic policy,” Nitze reflected three decades later in an ABC News series about the 20th Century hosted by Peter Jennings. “We would not only fully support the government in Vietnam but we would assume responsibility for their war with the Vietcong. Now some people wanted us to take a more limited role in the fighting and were quite vocal about it, but our policy would not allow that.”

By refusing to limit American involvement in the Vietnam conflict, President Jackson had set the country on an irreversible course. The United States of America would either save South Vietnam from being taken over or suffer a major defeat at the hands of her enemies. The Vietnam War, whose seeds had been planted in the postwar years of the Dewey Administration, was on.

The answer is "Yes". When LBJ historically made the decision to escalate American involvement in Vietnam in 1965, the opinion polls showed that a majority of Americans supported escalation. It wasn't until Vietnam turned into a never-ending quagmire with undefined victory goals that public support plummeted.

The Chinese position in supporting the Vietcong is one of convenience, not ideology. The government in Nanjing is Paternal Autocrat, with Chiang Kai-shek calling the shots. The Chinese want to get rid of the US-supported regime in South Vietnam and the Vietcong just happen to share the same goal. As for the economic question, the answer is "Yes". Although China TTL isn't Communist and the Chinese people are somewhat better off (they have a television cooking show for instance), they still have to live under the control of a dominating regime.

Thanks. Wait until you see the next update, Jape.

Kurt_Steiner: The question?

H.Appleby: I'm not sure what this question is exactly.

Of course, one should keep in mind that the borders were drawn courtesy of HOI. The odd-looking division of Manchuria between China, Mongolia, and the Soviet Union is the result of those three countries controlling the respective provinces. While Manchuria looks weird, I rather like it because it reinforces just how balkanized China became in my HOI game. And then there's Tibet, free (for now) and enjoying the status of being the Switzerland of Asia.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Vietnam War Begins

In May 1962:

- Marvel Comics publishes the first issue of “The Incredible Hulk”, introducing the powerful superhero and his human alter ego Dr. Bruce Banner.

- The Republic of China establishes the Golden Tiger Awards to honor the best in Chinese-language films. The Chinese equivalent to the American Academy Awards, the Golden Tiger Awards is part of the government’s campaign to promote Chinese culture.

- In England, band manager Brian Epstein convinces record producer George Martin to sign his group The Beatles to the Parlophone record label despite the fact that Martin had neither seen nor heard the Liverpool-based rock band.

- Eighty-two-year-old retired General Douglas MacArthur returns to the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York to accept the Sylvanus Thayer Award honoring his outstanding service as one of the nation’s greatest generals. In his half hour-long acceptance speech, delivered entirely from memory, MacArthur eloquently spoke of Duty, Honor, and Country.

- After months of development by a group of students, “Space War” goes live at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. One of the first digital computer games, two players each controlled starships and attempted to destroy each other while avoiding the gravitational pull of a central star. The MIT students developed “Space War” as a way to demonstrate the ability of computers to provide entertainment.

(It was in the 1960s that electronic gaming, today a multi-billion dollar industry, started to take shape)

According to opinion polls taken at the start of May 1962, a majority of the American public supported the President’s decision to deploy troops to the Dominican Republic and South Vietnam. The Gallup Poll put that number at 73 percent. Despite the fact that the country would suffer casualties, many Americans expressed confidence in the President to lead the country through to a victorious conclusion. There was no such thing as a “credibility gap” at the time. If Scoop Jackson said it was necessary to be involved in these two countries, the public was willing to believe him. As one historian has duly noted, “The American people trusted their Presidents to solve the problems of the world.”

Jackson could count on the public to have his back; Congress...not so much. By contrast, the President’s speech received a mixed reaction on Capitol Hill. The reason: Vietnam. Whereas there was general Congressional consensus that troops needed to be sent to the Dominican Republic, the decision to send troops to South Vietnam sharply divided Congress along ideological lines. The resulting debate became a replay of the reaction to the United Nations Speech the previous March. Liberals were openly skeptical of the President’s Vietnam policy. Despite the fact that he said that US involvement in that country came with an exit strategy, liberals openly expressed doubt that US forces could achieve the objective of knocking out the Vietcong. “The French couldn’t win over there,” one Democratic Senator noted, “And the President honestly believes we can do better?”

Several top Democrats said their biggest fear was that the US would get badly bogged down trying to fight guerillas in a jungle environment that clearly benefitted the defenders. Appearing on NBC’s “Meet the Press”, Senate Majority Leader Hubert Humphrey was asked about the President’s handling of the Vietnam issue. Humphrey admitted that “the President’s belief that we can settle the problems we are facing [in South Vietnam] with a military solution” gave him “a bad feeling.”

To say that Jackson wasn’t happy with the response he was getting from liberals is an understatement. He had spent weeks on developing this strategy, even tossing and turning in bed at night as the exact number of soldiers to send raced around his mind. It was hard for him to make the final decision, knowing that people would die on his order. Still, he made the call because it was his conviction that South Vietnam was worth fighting for. Now liberals, not having agonized over the decision, were second-guessing the Commander-in-Chief in a knee-jerk fashion and were calling the strategy “unwinnable” before it even had the chance to be implemented. Jackson was deeply indignant...and he showed it. In his speeches educating the American people about the country’s vital stake in Vietnam, the President warned his listeners not to be swayed by what he saw as the Left’s unrealistic view of foreign policy. Though he didn’t mention anyone by name, Scoop criticized liberals in general for not wanting to “bear the burden of a long and difficult struggle. They are impatient for some quick and easy solution to the threats that other nations pose. They want things to be done cheaply and immediately. It is when they cannot get any of this that they become hostile towards doing anything.”

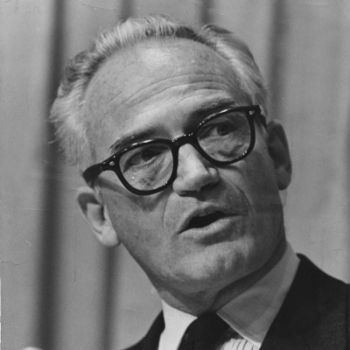

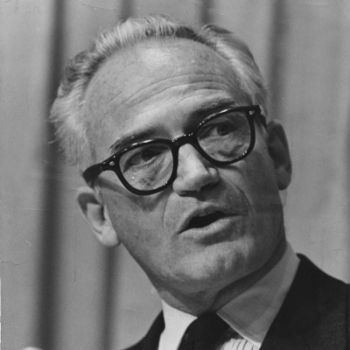

Conservatives on the other hand praised his Vietnam policy as one standing up for America’s interests in Southeast Asia. According to the Right, the United States had to do everything possible to stop the much hated Chinese enemy and that doing anything less amounted to appeasement. In their joint press conference, Republican Congressional leaders Charles Halleck and Everett Dirksen both endorsed Jackson’s use of America’s military muscle to decisively defeat the Chinese drive south. “I agree that obviously we cannot retreat from our position in Vietnam,” Dirksen remarked in his often rambling manner. “It is a difficult situation, to say the least, but we are in and we are going to have to muddle through for a while and see what we do.”

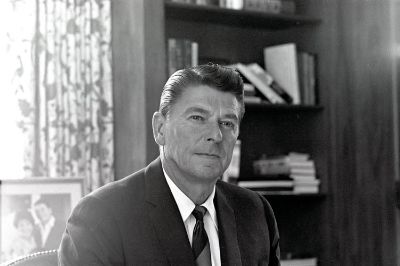

California Senator Richard Nixon, who attacked the Administration whenever possible as part of his strategy of raising his national profile heading into 1964, expressed his support in a back-handed way. The politically opportunistic first-term Senator said that he was glad to see Jackson putting boots on the ground “in order to avoid losing Vietnam like he lost Laos.”

Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, having just published a book laying out a conservative agenda for America, made no bones about what he thought:

“We are at war in Vietnam, and the President – who is Commander-in-Chief of our forces – has gone on the record of saying that the objective over there is victory. The President has drawn the line against aggression, and is being honest with the American people about our full participation. I know he will not allow our finest men to die on battlefields unmarked by purpose.”

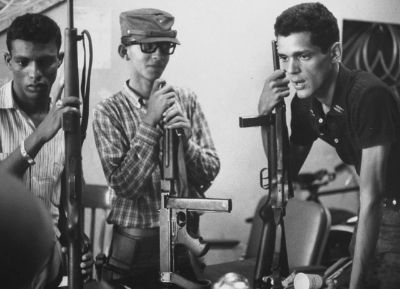

During the summer of 1962, while the seasonal joy of having fun at the beach was being reflected by a popular new single from The Beach Boys called “Surfin' Safari”, the President’s Vietnam policy was implemented. As the Americans started moving more of their men and weapons into South Vietnam, they ran into resistance thrown up by Saigon. The South Vietnamese generals who were in charge of the country had been greatly offended by the April 27th speech. They bristled with outrage at the suggestion that they were incapable of defending the country on their own and therefore needed the Americans to come in and turn the place into a US protectorate. “They are refusing to cede too much control,” General Maxwell Taylor cabled Washington on June 23rd. The South Vietnamese generals were trying to look tough, refusing to acknowledge any great need for help by outside forces. Their control of the Vietnamese press allowed them to take their “How dare you suggest we’re weak!” anger out on the American soldiers and newsmen stationed in their country. These complaints in turn irritated the Americans, who felt that the Vietnamese were completely missing the point of their presence. In July, Jackson dispatched Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to Saigon to try to talk sense into the generals as only he could. “You fellows need to understand,” LBJ loudly declared while staring straight into the eyes of the South Vietnamese leadership, “We’re not here to run your country for you! We’re here to stop the Chinese from running your country for you!”

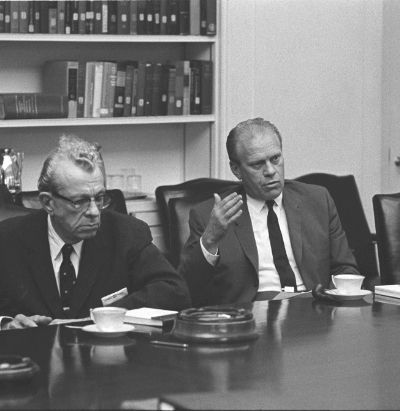

Despite getting The Johnson Treatment, the generals refused to drop their accusations that the Americans were deliberately mischaracterizing them in order to make them look bad and justify their intervention. Evidently they feared the appearance of weakness more than the existential threat being posed by their neighbors to the north. This tension complicated the US mission in South Vietnam while it was still getting off the ground. “How can we defend the country,” Joint Chiefs Chairman David L. McDonald asked rhetorically at a national security meeting held that summer, “If they will not allow us to?”

“We could get rid of them,” Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze said half-jokingly and half-seriously. CIA Director John McCone regretfully shook his head at the suggestion:

“The problem with that, Mr. Secretary, is that there is no one else in Vietnam who could take over. These generals are all we have to go with.”

Scoop sunk into his black leather seat and sighed. At that moment, he wasn’t sure who was worse: his enemy or his ally.

(Among the Americans being deployed to South Vietnam in 1962 was a twenty-five-year-old Army captain from New York City named Colin Powell)

Despite the resistance he was getting from the South Vietnamese generals, the President resolved to “muddle through” and stick with the plan that was currently being put into place. Perhaps once the pressure from the Vietcong had been lifted, the Americans could deal with the stubborn generals on a better footing. For now, Jackson thought, they had to continue pursuing the mission that he had laid out before the nation. As the summer wore on, the pace of deployment quickened. Even before all 40,000 American combat soldiers had arrived (deployment completion was scheduled for the autumn of 1963), Taylor was committing the soldiers he had under his command to limited firefights with the Vietcong. He wanted his men to gain experience now in order to prepare them for the tougher battles that were to come. As helicopters arrived in the country, Taylor immediately sent them out into the field. They were a quick way to move men into and out of the fighting, which was important in South Vietnam’s jungle environment.

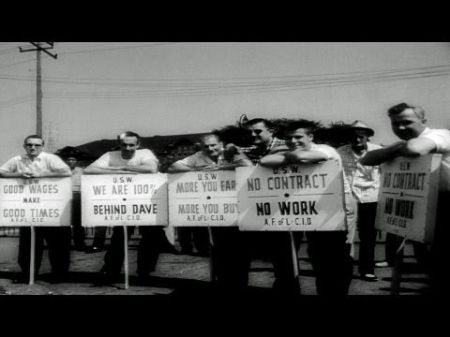

In the autumn of 1962, publicity about America’s combat role in Vietnam was everywhere. Across the country, articles about the fighting were appearing in newspapers both large and small. On television, newsmen like Walter Cronkite of CBS were doing segments about the growing conflict on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. With all this domestic publicity, it should come as no surprise that Vietnam became an issue in the November midterm election. Republican candidates generally demanded full military commitment to Vietnam in order to guarantee victory; some on the Right even went as far as to suggest that nuclear war should be risked. If the war against the Vietcong became a losing cause, the Republicans would be ready to blame the President for not having done more. Democratic candidates on the other hand were generally more cautious about getting the country involved in this conflict. Wanting to distance themselves from their hawkish standard-bearer, the Democratic position on Vietnam was more-or-less:

“The Vietnamese need to stand on their own two feet. We cannot and should not do the fighting for them.”

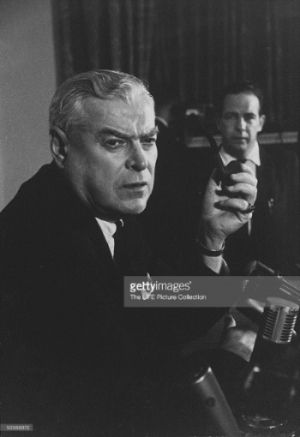

It wasn’t just Democrats who were expressing skepticism at the way Jackson was handling Vietnam. By the middle of October 1962, six months after he had given Taylor the green light, the President was facing questions from reporters over the strategy. With eleven Americans killed in combat missions so far, the press raised concerns about the US military operation in Vietnam. At one press conference, a reporter asked Jackson, “Why should American troops do the bulk of the fighting in Vietnam?”

Jackson answered that it was necessary to fight the guerrillas because the South Vietnamese Army wasn’t strong enough yet to do it by themselves. Then came the follow-up questions. But what about the South Vietnamese leadership? Didn’t they oppose allowing the Americans to take the war to the enemy on their behalf? The President attempted to downplay the generals’ opposition, stating rather weakly that all allies have their differences. “What is important is that we do not allow these differences to distract from our ability to work together in a common purpose.”

The press kept asking questions. With almost 17,500 soldiers stationed in Vietnam by Thanksgiving, was the strategy of having them actively engage the Vietcong a good one? Here the President went out of his way to defend the man behind the strategy. “General Taylor,” he insisted, “Has the confidence of everyone here [in the Administration]. He has demonstrated on numerous occasions that he is a man of sound mind and cool judgment. The reason he is in Vietnam is because he is the best General we have in the Army. You can ask anyone and they will tell you the same thing I told you.”

Scoop reminded everyone that it was Taylor who had commanded the US military mission in Yugoslavia during the 1950s. He credited Taylor’s leadership for helping the Royal Yugoslav Army squash a Communist insurgency that threatened to topple the pro-West royalist regime in Belgrade. The Commander-in-Chief even went as far as to say that “the people of Yugoslavia are enjoying freedom today instead of being trapped behind the Iron Curtain because of General Taylor.”

Although he was stretching things a bit, that claim illustrated Jackson’s confidence that if Taylor could handle the Balkans, he could handle Southeast Asia.

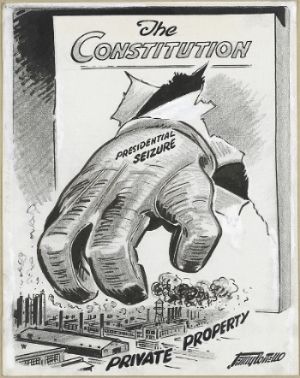

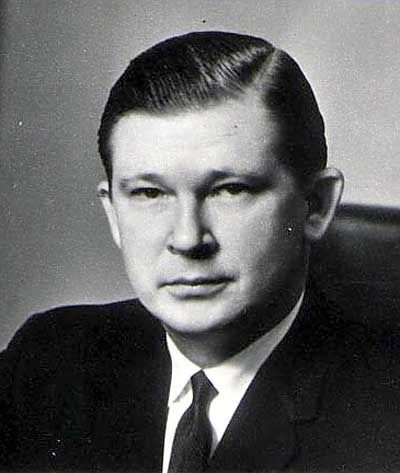

Throughout his Presidency, Henry M. Jackson displayed decisiveness. Once he made a decision to do something, he did it and that was it. He wasn’t someone who second-guessed himself. While decisiveness can be a good trait for a leader, it sometimes got Jackson into trouble. He could be at times too decisive, appearing reckless in his decision-making. That was how liberals felt about him on Vietnam. They felt Jackson was plunging the United States into a war that she didn’t really need to fight; worse, he didn’t seem to care about the human cost that families across the country would have to bear. In the eyes of liberals like South Dakota Senator George McGovern, the leader of the Democratic Party was too hawkish for their comfort. Needless to say, the President didn’t see it that way. When warned by Democratic National Committee Chairman John F. Kennedy in late 1962 that he was “provoking a major furor” within the Democratic Party “over the undeclared war in South Vietnam”, Scoop shot back that it was the fault of the liberals and not his. He stood firm, refusing to back down in the face of liberal criticism. The President displayed his defiance on January 14th, 1963 when he appeared before a joint-session of Congress to deliver the 1963 State of the Union Address. He responded to his opponents by vigorously defending his decision to get the country deeply involved in Vietnam:

“We have sent combat troops there not to conquer but to prevent conquest. We have sent combat troops there not because it is something to do, but because it is the right thing to do. Our brave men are fighting not because they want to fight, but because the forces of tyranny require them to fight for freedom.”

“That was our basic policy,” Nitze reflected three decades later in an ABC News series about the 20th Century hosted by Peter Jennings. “We would not only fully support the government in Vietnam but we would assume responsibility for their war with the Vietcong. Now some people wanted us to take a more limited role in the fighting and were quite vocal about it, but our policy would not allow that.”

By refusing to limit American involvement in the Vietnam conflict, President Jackson had set the country on an irreversible course. The United States of America would either save South Vietnam from being taken over or suffer a major defeat at the hands of her enemies. The Vietnam War, whose seeds had been planted in the postwar years of the Dewey Administration, was on.

Last edited: