20.3. ŠĀBUHR I’S SECOND CAMPAIGN. THE BATTLE OF BARBALISSOS.

Let’s look now at events in the East, which are much less clear than the ones in Europe. As I said before, the exact chronology of Šābuhr I’s second campaign is hopelessly unclear, other than the events seem to have taken place wholly during Trebonianus Gallus’ short reign (summer 251 – August 253 CE). The first act of the play was the Sasanian seizure of Armenia, which probably happened during Decius’ Gothic war or immediately after it, taking advantage of Roman troubles at the Danube. If that was the case, then the decision of granting asylum to the Armenian prince Trdat was either one of Decius’ last decisions or one of Trebonianus Gallus’ first ones. Both would have been probably well aware that such a decision was a breach of the 244 CE treaty and would mean war against Šābuhr I.

This decision was taken at a disastrously bad moment for Rome, but probably any Roman leader would have done the same. The fate of Armenia was just too important to just concede victory to Šābuhr I. Armenia was the piece that gave an edge to any of both empires in the Middle East, and Rome had controlled it for two centuries. Allowing Šābuhr I to just take it with impunity was simply unacceptable; and we should remember what happened to Maximinus Thrax for ignoring Ardaxšir I’s conquest of Roman Mesopotamia, which had lesser strategic importance than Armenia. Rome had to react, but as the events that followed would show, the empire was just not able anymore to concentrate overwhelming forces in a single front when it suited it like it had been able to do since Augustus’ times. Now, it was Rome’s enemies who would set the pace of events, and the Romans would be forced to react to them as well as they could.

In his influential 1980 paper, Christol noted a telling sign that Trebonianus Gallus was preparing himself for war against the Sasanians. After 244 CE, the mint of Antioch had been issuing large amounts of billon tetradrachms (many eastern cities issued their own coinage), a production that was maintained under Philip (perhaps the only sign that could point towards a continuation of military operations in the East under this emperor) and Decius. The billon tetradrachm was the local equivalent of the Roman billon coin of the period, the

antoninianus. Under Trebonianus Gallus, the issuing of tetradrachms ceased abruptly and was substituted by an equally massive production of regular

antoniniani, the coin with which soldiers’

stipendia were paid, hinting at an upcoming military campaign in the East which would have included western troops which would have been used to being paid in

antoniniani, the same had happened during Gordian III’s eastern campaign. The only difference is that under Gordian III a large amount of

antoniniani had been minted at Rome and transported to the East, while under Trebonianus Gallus and his successors the mint at Antioch seems to have been in charge for the totality of the money supply. Another telling sign is that one of the main legends in the reverse of the

antoniniani that were being massively issued by the mint of Antioch at the time read

ADVENTUS AVGG, thus proclaiming the imminent arrival of the two

augusti (Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus) in the East.

Antoninianus of Trebonianus Gallus; on the reverse, ADVENTUS AVG.

As we’ve seen in the cases of Severus Alexander and Gordian III, launching an eastern expedition would have been a cumbersome affair, and it usually took an emperor between one and two years of preparations and marches before he reached the East with reinforcements from the West. And if there was something that Trebonianus Gallus probably did not have, it was time.

Either in the last months of Decius’ reign or during the first months of Trebonianus Gallus’ one, there had been some local trouble in Antioch of the kind that in normal circumstances should have never gone beyond a mere local anecdote, but these were not normal circumstances. It sounds like the plot of a bad movie, but several ancient sources corroborate the tale. First, the SHA (in the chapter

Triginta Tyranni):

This man (Myriades), rich and well-born, fled from his father Cyriades when, by his excesses and profligate ways, he had become a burden to the righteous old man, and after robbing him of a great part of his gold and an enormous amount of silver he departed to the Persians. Thereupon he joined King Sapor and became his ally, and after urging him to make war on the Romans, he brought first Odomastes and then Sapor himself into the Roman dominions; and also by capturing Antioch and Caesarea he won for himself the name of Caesar. Then, when he had been hailed Augustus, after he had caused all the Orient to tremble in terror at his strength or his daring, and when, moreover, he had slain his father (which some historians deny), he himself, at the time that Valerian was on his way to the Persian War, was put to death by the treachery of his followers. Nor has anything more that seems worthy of mention been committed to history about this man, who has obtained a place in letters solely by reason of his famous flight, his act of parricide, his cruel tyranny, and his boundless excesses.

John Malalas, (an Antiochene author from the VI century CE, quoting the III century author Philostratos of Athens and local traditions from his native city):

Under this emperor (i.e. Valerian), one of the magistrates of Antioch the Great by the name of Mariades was expelled from the city council (boule) at the contrivance of the entire council and citizen body. He was found wanting in his administration of the chariot races, for whenever he was leader of the faction, he did not purchase horses but kept for his own benefit the public funds destined for the circus. He departed for Persia and offered to betray Antioch the Great, his own native city, to Shapur the king. This Shapur, the king of the Persians, came with a large force through the limes of Chalcis and occupied and devastated the whole of Syria. He captured Antioch the Great in the evening and plundered it, tormented it and set it on fire. Antioch then was in her three hundred and fourteenth year (=AD 265/6?). However, he decapitated the magistrate (i.e. Mariades) for his betrayal of his native city.

Another source is the VI century CE East Roman author Peter the Patrician (a high-ranking member of the administration of Justinian I):

When the king of the Persians came before Antioch with Mariadnes (i.e. Mariades), he encamped some twenty stadia (from the city). The respectable classes fled the city but the majority of the populace remained: partly because they were well disposed towards Mariadnes and partly because they were glad of any revolution; such as is customary with ignorant people.

What modern scholars have managed to put together from this garbled mess is that a man named Kyriades or Mariades, a rich and respected member of the Antiochian elite, was expelled from the city’s

boule (governing assembly) either for embezzling public funds or for robbing his family, or both. This should have been the end of the affair, but this Kyriades/Mariades crossed into

Ērānšahr and offered his help to Šābuhr I, who was planning an attack against the Romans and accepted the offered help gladly; judging by all the sources he acted moved by hatred and revenge against his native city although the SHA (beware the source) state that he also tried to usurp the purple with Šābuhr I’s help (who could have found this an useful distraction in his war against the Romans). The SHA also offer an important detail that scholars consider probably true: he names an “Odomastes”, whom modern scholars identify as none other than Hormizd-Ardaxšir, Šābuhr I’s heir presumptive and who had just been appointed as Great King of Armenia by his father.

Reconstructed computer view of ancient Antioch, as seen from the wall of the island on the Orontes, looking towards Mons Silpius, the mountains that dominated the city on its southern side.

The tale of Mareades is absent from the ŠKZ, but its historicity is confirmed by his mentioned in the only surviving Graeco-Roman contemporary source, the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle. Due to its importance, I’ll quote here at length the whole passage dealing with the Sasanian invasion and the events that immediately preceded it:

(107) And after him there shall rule powerfully

O'er fertile Rome another great-souled lord

Versed in war, coming from the Dacians

And numbering three hundred; he shall have

Also the letter of the number four,

And many shall be slay, and then the king

Shall all his brothers and his friends destroy

Even while the kings are cut off, and straightway

Shall there be fights and pillagings and murders

Suddenly on the older king's account.

(117) Then, when a wily man shall summoned come

A robber and a Roman not well known

From Syria appearing, he by guile

Into a race of Cappadocian men

Shall drive through and, besieging, shall press hard,

Insatiate of war. And then for thee,

Tyana and Mazaka, there shall be

A capture; thou shalt be enslaved and put

Upon thy neck again a fearful yoke.

Arid Syria shall mourn for men destroyed

And then Selenian goddess shall not guard

Her holy city. But when he by flight

From Syria shall before the Romans come,

And shall pass over the Euphrates' streams,

No longer like the Romans, but like fierce

Dart-shooting Persians, then, fulfilling fate,

Down shall the ruler of the Italians fall

In the ranks smitten by the gleaming iron;

And close upon him shall his children perish.

But when another king of Rome shall reign,

Then also to the Romans there shall come

Unstable nations, on the walls of Rome

Destructive Ares with his bastard son;

(140) Then also shall be famines, pestilence,

And mighty thunderbolts, and dreadful wars,

And anarchy in cities suddenly;

And the Syrians shall perish fearfully;

For there shall come upon them the great wrath

Of the Most High and straightway an uprising

of the industrious Persians, and mixed up

With Persians shall the Syrians destroy

The Romans, but by the divine decree

They shall not make a conquest of their laws.

Alas, how many with their goods shall flee

Front the East unto men of other tongues

Alas, the dark blood of how many men

The land shall drink! For that shall be a time

In which the living uttering o'er the dead

A blessing shall by word of mouth pronounce

Death beautiful and death shall flee from them.

(157) And now for thee, O wretched Syria,

I weep in sorrow; for to thee shall come

A dreadful blow from arrow-shooting men,

Which thou didst never think would come to thee.

Also the fugitive of Rome shall come

Bearing a great spear, Crossing on his way

Euphrates with his many myriads,

And he shall burn thee, and dispose all things

In a bad way. O wretched Antioch,

And thee a city they shall never call,

When by thy lack of prudence thou shalt fall

Under the spears; and stripping off all things

And making naked he shall leave thee thus

Coverless, houseless; and when anyone

Sees he shall of a sudden weep for thee.

(172) And thou shalt be, O Hierapolis,

A triumph, also thou, Berœa; weep

At Chalcis over lately wounded sons.

Alas, how many by the steep high mount

Of Casius shall dwell and by Amanus

How many, and how many Lycus laves,

And Marsyas as many and Pyramus

The silver-eddying; for even to the bounds

Of Asia they shall treasure up their spoils,

Make cities naked, and bear idols off

(182) And cast down temples on much-nourishing earth.

It reads like utter gibberish, and the fact is that the text is so dense with allegories and metaphors related to Jewish scripture and Graeco-Roman mythology and historical lore in its attempted imitation of oracular speeches that after more than a century of heated debate scholars are still in disagreement about the events it “prophesized” (the original text was written in Greek).

I’ll summarize now the reconstruction of events by the German scholar Udo Hartmann, which align with the prevailing view amongst scholars, and then I’ll expose the differing version defended by David S. Potter, who has devoted a long book to analyze the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle.

According to Hartmann, the war began in 252 CE with a Sasanian invasion of Roman Mesopotamia and a Roman counterattack, presumably to avoid the Sasanian capture of Nisibis (as described by al-Tabari and Eutychius). Most probably Nisibis fell at this time, because its mint ceased issuing Roman coins abruptly around this time. And the next year, it would be Šābuhr I’s turn to invade the Roman empire.

Hartmann construes the verses 117-130 as a description of Iotapianus’ rebellion, and according to him the verses 131-134 describe the death of Decius and his son in campaign against the Goths. From the verse 135 onwards, the “Sibyll” writes about the eastern events that happened during Trebonianus Gallus; short reign, in which is a long mourning of the destruction of Syria by the Sasanian army. Verses 142-148 attest to “Syrians” collaborating with “Persians” against “Romans”. According to Hartmann, this is a reference to the fugitive Antiochene leader Mareades.

He reconstructs the original name as “Mareades” from among all the variants transmitted in the sources. Hartmann notes that “Mareades” is the Hellenization of the Syriac common name “Mareas”. According to him, this man must’ve been a rich citizen of Antioch, and he must’ve served as a member of the city assembly (the

boule), and would have been elected in 252 CE by the

boule to be in charge of financing the chariot races at the circus, one of the acts of evergetism that the members of local governments were expected to provide to theirs fellow citizens at their own expense. This was a potentially ruinous commission (several cases of ruined local magistrates are known from across the empire due to similar obligations), and Hartmann thinks that this was probably the case for Mareades. Due to his failure at financing the chariot races, he was expelled from the

boule (probably he was elected for this “honor” deliberately by political enemies who wanted to see him ruined), and he left Antioch and went to

Ērānšahr to offer his services to Šābuhr I, then at war against Rome, perhaps taking with him funds that the

boule of Antioch considered to be public funds (the money destined for the races) and Mareades considered to be his own money.

Mareades is described by ancient sources as having accompanied Šābuhr I in his invasion, and most scholars consider verses 142-148 to corroborate this. According to several sources, Mareades had a following in Antioch, and Hartmann thinks that these supporters would have been important for the fall of the city in Šābuhr I’s hands.

According to Hartmann, the invasion was launched by Šābuhr in the spring of 253 CE. About the chosen route there’s consensus among scholars; Šābuhr achieved strategical surprise by ignoring the western Mesopotamian cities (Carrhae and Edessa) still in Roman hands: he advanced by a completely unexpected route and aimed his attack directly against northern Syria (the Roman province of Syria Coele) with its capital Antioch, which was the main city and military center of the Roman East.

The route chosen was the Euphrates route, so often used by the Romans in their eastern attacks. But while for the Romans it made sense (as it allowed for the shipping of supplies downstream), this would be not possible for a Sasanian army advancing north against the current’s flow. It was probably the last thing that the Romans would have expected Šābuhr I to do. Taking this route implies several things:

- First, that Šābuhr I had a comfortable numerical superiority over the Romans, for such an advance would leave several Roman and Palmyrene fortified outposts (Anatha, Dura Europos, Circesium and others) in his rearguard which would have needed several strong enough Sasanian detachments left behind to surround and blockade them. And he would also have needed to guard his vulnerable left flank and rearguard against surprise Palmyrene attacks. This suggests the mobilization of a large army from all the corners of his vast empire, and such a mobilization would’ve needed to be planned in advance, if forces from eastern Iran, central Asia, Afghanistan and perhaps further away had to be ready on time (in the IV century, Ammianus Marcellinus attested the presence of contingents from Kušanšahr and Kidarite central Asian nomads in Šābuhr II’s army during one of his Mesopotamian campaigns). Such forces would have needed to cross the Iranian plateau and the Zagros passes and meet with Šābuhr I’s royal army near Ctesiphon. Given the inhospitable weather in the Iranian plateau and the Zagros (not to speak of central Asia and Afghanistan) in winter, it’s unlikely that such a force could have been ready very early in the campaign season.

- Second, that the Sasanian king must’ve had some sort of logistical preparations ready to feed such a large force and carry the supplies upstream.

- Third, that this bold move put the Romans on the strategical defensive, but it did not rend them unable to respond. The Romans had shorter communication lines and an excellent road and supply system that would have allowed them to concentrate their forces quickly when Šābuhr I’s intentions became evident. What they lost though was the sheltering screen provided by the fortified cities of northern Mesopotamia, and as we shall see soon, by the Euphrates river itself.

- Fourth, that Šābuhr I’s advance can’t have been very fast; he was moving with a large army, had to carry his supplies upstream and there’s evidence that he carried with him infantry forces and a siege train. This was not a large-scale cavalry raid, but a combined-arms invasion army well equipped and prepared. Again, this implies that the Romans must’ve had enough time to prepare themselves and gather their forces.

- Fifth, that Šābuhr I advanced along the right bank of the Euphrates, with the Syrian desert to his left. Advancing along the other bank would have prevented the danger of Palmyrene attacks from the desert, but it would have meant that the Roman army could have blocked any attempts to cross the river. Or worse still, it could have trapped the Sasanian army with its back to the river during the crossing, forcing it to fight a frontal battle without being able to use its cavalry advantage to full effect, like it happened to Šābuhr II at Singara (a narrowly avoided disaster) and at the catastrophic Sasanian defeat at Qadisiyyah against the Rashidun army in 637 CE.

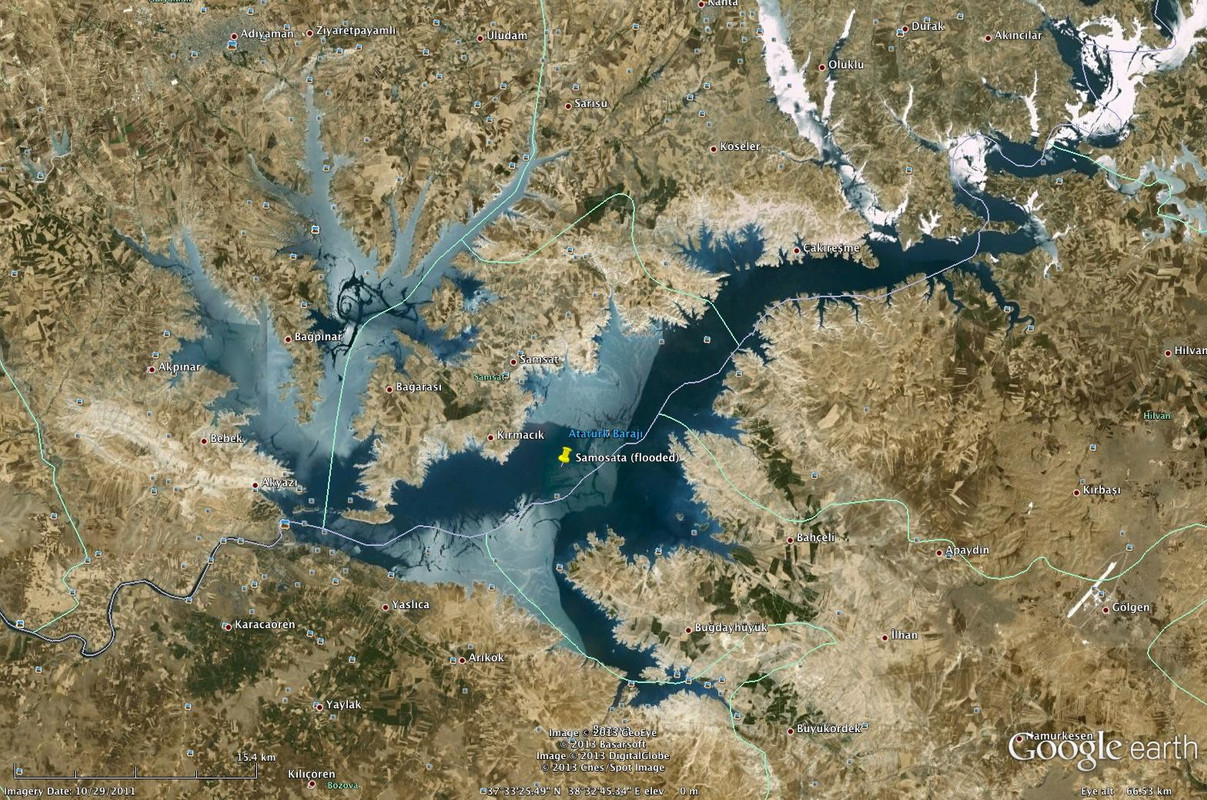

The possibility that Šābuhr I must’ve enjoyed a numerical advantage and that he advanced along the Euphrates’ right bank is reinforced by the place where the decisive encounter took place: the Syrian town of Barbalissos (modern Balis), a small town located on the Euphrates’ western bank, where the river’s great western bend reaches the point closest to the Mediterranean coast (about 200 km).

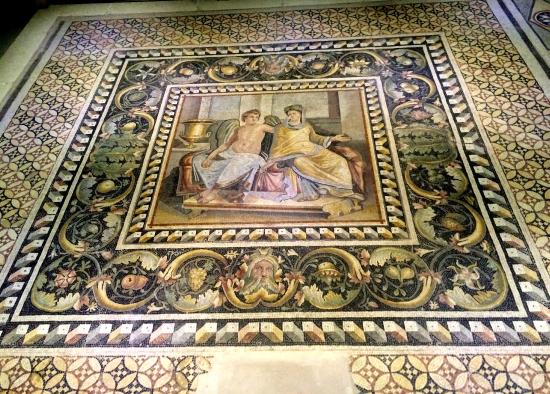

Hypothetical advance of Šābuhr I's army along the western bank of the Ephrates river. Anatha was the first Palmyrene fortress on the river, and Doura (Dura Europos) was the first Roman fortress. As you can see, Barbalissos is already dangerously close to Antioch and the Mediterranean coast.

This was a defensive battle for the Romans, because they gathered their army in a place from which they could try to block Šābuhr I’s advance to Antioch and the Mediterranean coast. The scarcity of sources is such that only the ŠKZ even names the battle of Barbalissos: this name or even the fact that there was a battle is completely absent from Greek and Latin sources. It’s the same situation as with Mishike, but as with this last battle some historians are still skeptical about the veracity of the ŠKZ’s depiction of events, there’s consensus that the battle of Barbalissos really happened and ended with a crushing Roman defeat, by the simple fact that some surviving Greek and Latin sources confirm the tale of the ŠKZ about the devastation of Syria and the destruction of Antioch by Šābuhr I’s army; this could only have happened if the Roman army of the East had been severely beaten (or if it had banished into thin air).

Barbalissos is today an abandoned ruin; in ancient times it was a small town inhabited by an Aramaic-speaking population and emperor Justinian I surrounded it with strong fortifications, whose ruins are still visible. Archaeological digs have been done at this site, and scholars believe that in the III century the town was not fortified. Today it lays partially submerged under the waters of the Assad lake (a dam on the Euphrates built in modern times). The surrounding country is slightly hilly, but other than that it has no major obstacles to major troop movements (rivers, ravines, mountains, etc.). In other words, this was perfect terrain for cavalry, which did not bode well for the Romans; as Barbalissos lacked fortifications, the only strong point to which the Roman army could retreat in case of retreat would have been their camp, if they had fortified it.

View of the environs of Barbalissos in modern times; in the background the waters of Lake Assad.

But the major unanswered questions about the battle of Barbalissos don’t end with the nature and disposition of the battlefield; we don’t know who commanded the Roman army and how many men were involved on both sides. The ŠKZ says that at Barbalissos the Sasanian king “annihilated” a Roman army of 60,000 men. This number is usually considered an exaggeration, but given the number of men available to the Romans in the East and the fact that probably they had plenty of time to concentrate their forces, in my opinion the number is perfectly plausible (they were even operating very near their main supply bases, and in a fertile and populous countryside, with plenty of supplies and water available).

In his book

The army of Severus Alexander, Bernard Michael O’Hanlon gives hypothetical numbers for the numbers of men garrisoned in each province at the end of the last Severan emperor in 235 CE; these numbers are still probably valid for 253 CE. O’Hanlon follows Hyginus for the strength numbers of each unit but considers that units would have probably at all times been at least 10% short of their paper-strength. The list is based primarily on epigraphic source, those units whose presence in the eastern provinces is unsure are marked with a question mark.

- Full legion: 5,000 men (including 120 cavalrymen)

- Auxiliary cohors (also called cohors quingenaria): 480 infantrymen.

- Auxiliary cohors milliaria: 800 infantrymen.

- Auxiliary cohors equitata (quingenaria): 480 infantrymen and 120 cavalrymen.

- Auxiliary cohors milliaria equitata: 800 infantrymen and 240 cavalrymen.

- Auxiliary ala (quingenaria): 480 cavalrymen.

- Auxiliary ala milliaria: 720 cavalrymen (a very rare unit, only 6 are attested for the whole empire).

For the eastern provinces, the list of units given by O’Hanlon for the end of Severus Alexander’s reign is:

Cappadocia: c. 19,000 infantrymen and 2,800 cavalrymen, broken down as:

- Legio XV Apollinaris.

- Legio XII Fulminata.

- Ala II Ulpia Auriana.

- Ala I Augusta Gemina Colonorum.

- Ala II Gallorum.

- Ala I Ulpia Dacorum.

- Cohors Apuleia. C. R. (for Civites Romanorum, a title which became redundant after the Constitutio Antoniniana)

- Cohors Bosporiana Milliaria.

- Cohors Milliaria Equitata C. R. (?).

- Cohors I Apamenorum Sagittariorum.

- Cohors I Claudia Equitata.

- Cohors I Germanorum Milliaria Equitata.

- Cohors I Lepidiana Equitata C. R.

- Cohors I Germanorum.

- Cohors II Claudia (?).

- Cohors II Hispanorum (?).

- Cohors III Ulpia Petraeorum Milliaria Equitata.

- Cohors IV Raetorum.

Mesopotamia: c. 8,000 infantrymen (minimum) and 1,500 cavalrymen (minimum), broken down as:

- Legio I Parthica.

- Legio III Parthica.

- Ala Britannica.

- Ala Nova Firma Catafractaria Milliaria.

- Cohors I Ascalonitarum Felix Sagittaria.

- Cohors I Flavia Chalcidenorum.

- Cohors II Equestris.

- Cohors III Augusta Thracum.

- Cohors VI I(turaeorum).

- Cohors IX Maurorum.

Syria Coele: c. 20,000 infantrymen (O’Hanlon does not give the total number of cavalrymen, but if we add the strength of the units listed below, they add up to c. 6,300 cavalrymen), broken down as:

- Legio IV Scythica.

- Legio XVI Flavia Firma.

- Ala Thracum Herculiana Milliaria (?).

- Ala I Praetoria C. R.

- Ala I Ulpia Dromedariorum Milliaria (?).

- Ala I Ulpia Singularium (?).

- Ala II Flavia Agrippiana (?).

- Ala III Thracum (?).

- Cohors I Ascalonitanorum Sagittaria Equitata (?).

- Cohors I Augusta Pannoniorum.

- Cohors I Claudia Sugambrorum (?).

- Cohors I Flavia Chalcidenorum Sagittaria Equitata.

- Cohors I Lucensium Equitata (?).

- Cohors I Ulpia Dacorum.

- Cohors I Ulpia Petraeorum Milliaria Equitata (?).

- Cohors I Ulpia Sagittaria Equitata (?).

- Cohors II Dacorum Equitata (?).

- Cohors II Equitum.

- Cohors II Classica Sagittaria (?).

- Cohors II Thracum Syriaca Equitata (?).

- Cohors II Ulpia Equitata C. R.

- Cohors II Ulpia Paphlagonum Milliaria Equitata.

- Cohors III Augusta Thracum Equitata (?).

- Cohors III Thracum Syriaca Equitata (?).

- Cohors III Ulpia Paphlagonum Equitata (?).

- Cohors IV Lucensium Equitata (?).

- Cohors IV Thracum Syriaca Equitata (?).

- Cohors V Chalcidenorum Equitata (?).

- Cohors V Ulpia Petraeorum Milliaria Equitata (?).

- Cohors VII Gallorum.

- Cohors XII Palestinorum Milliaria.

- Cohors XX Palmyrenorum Sagittaria Equitata Milliaria.

Syria Phoenicia: c. 10,000 infantrymen and 750 cavalrymen (here O’Hanlon makes an assumption that most of its auxiliary units must’ve been dropped from the record, for the list below doesn’t add up to the total above), broken down as:

- Legio III Gallica.

- Ala Vocontiorum.

- Cohors I Flavia (Chalcidenorum) C. R. Equitata.

- Cohors II Ulpia Galatarum.

Syria Palaestina: c. 18,500 infantrymen and 2,000 cavalrymen, broken down as:

- Legio X Fretensis.

- Legio VI Ferrata.

- Ala Anton(iniana?) Gallorum (?).

- Ala Gallorum et Thracum Ant(onin)iana (?).

- Ala VII Phrygum (?).

- Cohors I Damascenorum (?).

- Cohors I Flavia C. R. Equitata.

- Cohors I Montanorum (?).

- Cohors I Sebastena Milliaria (?).

- Cohors I Thracum Milliaria (?).

- Cohors I Ulpia Galatarum.

- Cohors II Ulpia Galatarum (?).

- Cohors IV Bracar(augustanorum) (?).

- Cohors IV Breucorum (?).

- Cohors IV Palestinorum.

- Cohors IV Ulpia Petraeorum (?).

- Cohors V Gemina C. R. (?).

- Cohors VI Ulpia Petraeorum (?).

- Numerus Maurorum (Moorish mercenaries from North Africa under Roman pay, led by their own officers and organized according to their custom, such units are impossible to quantify. Most probably, they were cavalrymen).

Arabia: c. 9,500 infantrymen and 2,000 cavalrymen, broken down as:

- Legio III Cyrenaica.

- Ala Celerum.

- Ala Dromedariorum.

- Ala Veterana Gaetulorum.

- Ala VI Hispanorum.

- Cohors I Augusta Thracum Equitata.

- Cohors I Hispanorum.

- Cohors I Thacum Milliaria.

- Cohors I Thebaeorum.

- Cohors III Alpinorum.

- Cohors V Afrorum Severiana.

- Cohors VI Hispanorum.

- Cohors VIII Voluntariorum.

- Gothi Gentiles (Gothic mercenaries under Roman pay, it’s probable that they were cavalrymen).

Egypt: c. 10,850 infantrymen and 2,500 cavalrymen.

- Legio II Traiana Fortis.

- Ala Apriana.

- Ala Augusta (Syriaca) (?).

- Ala Gallorum Veterana.

- Ala Herculanea.

- Ala I Thracum Mauretana (?).

- Ala II Ulpia Afrorum.

- Cohors Scutata. C. R.

- Cohors I Apamenorum Equitata.

- Cohors I Augusta Lusitanorum.

- Cohors I Augusta Pannoniorum.

- Cohors I Augusta Praetoria Lusitanorum Equitata.

- Cohors I Flavia Cilicum Equitata.

- Cohors I Pannoniorum.

- Cohors I Ulpia Afrorum (?).

- Cohors II Hispanorum (?).

- Cohors II Ituraeorum.

- Cohors II Thebaeorum (?).

- Cohors II Thracum.

- Cohors III Cilicum.

- Cohors III Galatarum.

- Cohors III Ituraeorum.

- Numerus Palmyrenorum (Palmyrene mercenaries under Roman pay, it’s almost sure that they were cavalrymen).

The grand total for the eastern Roman army according to O’Hanlon adds up to 113,700 men, including infantry and cavalry, which in my opinion means that a force of 60,000 men for the Roman army at Barbalissos is perfectly plausible. There are some commentaries to be made about the subject though (apart from the obvious fact that 18 years had passed since the death of Severus Alexander):

- The Romans would have also have had access to a considerable number of Palmyrene allied cavalry. Apart from the city’s own army, the Arabic rulers of Palmyra controlled most nomadic Arabic tribes in the Syrian and Arabic deserts, deep into Arabia.

- The different provinces would’ve contributed unevenly to the army. The army of Syria Coele would’ve been deployed almost in its entirety (as the battle was held within the province, which was the main target of the Sasanian attack). The army of Mesopotamia would’ve been in bad shape, as the province had been the target of a Sasanian attack the previous campaign season, which probably ended with the fall of Nisibis, and leaving such an exposed province ungarrisoned would have been unadvisable, so most probably most of it stayed in Mesopotamia east of the Euphrates. The other provincial armies would have contributed, but without leaving their own provinces unprotected, especially Cappadocia which now bordered Sasanian Armenia, and Egypt, a perpetually unstable province that was economically vital for Rome and just couldn’t be left unguarded.

- Apart from the two legions stationed in Syria Coele, which probably would have been deployed complete into the battlefield, the other legions would have been represented by vexillationes, as had been increasingly common since the II century CE. Apart from the unwillingness to leave provinces ungarrisoned, the legion had evolved into an administrative an organizational unit for the Roman army, and it was important to keep its basic structure in place in order to train new recruits; hence the unwillingness to risk having whole legions destroyed in battle by the Roman leadership.

- The cavalry forces listed above add up to 17,850 cavalrymen, which is 15% of the whole eastern Roman army. This number is in line with scholarly studies about Roman army deployment under Hadrian: about 20% of the total army strength was cavalry, and most of it was concentrated in the West and Africa west of Egypt. Surprisingly, this deployment stood the same under Severus Alexander, despite the growing threat from Arsacid and Sasanian cavalry-based armies. It’s probable that the Romans had previously made good for this weakness in the East through the use of allied cavalry (Armenians, Osrhoenians, Hatrenes, Palmyrenes, etc.). But by 253 CE only Palmyra remained as a Roman ally.

- The Roman army of the East seems to have received some reinforcements from the West, in small numbers but including significant units. In the mid-1980s a Belgian archaeological mission excavated the remains of the Syrian city of Apamea, and it discovered some interesting inscriptions. Apamea surrounded itself with a strong walled circuit in the late III century, and as elsewhere in the empire these walls were built in a hurry, re-using materials from cemeteries, ancient funerary monuments, etc. One of the towers of the wall (tower XV) was located relatively near to a ravine, and other side of the ravine there were the remains of the legionary camp of Legio II Parthica, which built it during Caracalla’s eastern expedition and re-occupied it again during Severus Alexander’s eastern campaign. But the camp seems to have been used by other Roman units when it was not being occupied by Legio II Parthica (whose permanent base was located at Alba near Rome). The ravine between the camp and the city of Apamea seems to have been used by Roman soldiers as a graveyard for their deceased comrades, and when tower XV was built, most of the gravestones of this military cemetery were used for as building material for this tower. The Belgian archaeological team disassembled the remains of the tower, and discovered a considerable number of gravestones, most of them of soldiers of Legio II Parthica which have helped considerably in the study of the Roman military in the Severan era. But apart from these tombstones, the Belgian team also discovered the gravestone of a certain Aurelius Bassus, a decurion of the Ala I Ulpia Contariorum, who’d died on 21 April 252 CE. The leader of the archaeological team, Jean-Charles Balty, reported on his paper about the digs that this is one of ten similar epigraphic inscriptions coming from Apamea that evidence the presence of cavalry units which had come from other parts of the empire in 252 CE (the Ala I Ulpia Contariorum was usually based in Pannonia). The presence of these units, and the facts that they all are cavalry units, its linked by Balty explicitly to the campaign that ended with the battle of Barbalissos.

The second great unknown issue is that of the identity of the Roman commander. Each provincial army was led by the provincial governor, and in order to gather an army including forces from several provinces it was necessary for the emperor himself to be present, or to appoint a really trustable commander (considering the long list of usurpations at the time, this was obviously a very delicate issue). Well, we ignore completely who this commander might have been. If according to Hartmann and most scholars the battle happened in the summer of 253 CE, then Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus couldn’t have been present, as they were in Italy fighting against, and perishing under Aemilianus’ attack according to ancient sources. And Valerian was in Raetia, or in Alamannic territory. Who was in command of the eastern armies? There’s not a single source that offers an answer or even a hint at this key issue. David S. Potter proposes an alternative chronology for events and hypothesizes that the battle could’ve happened in the campaign season of 252 CE, which could have meant that perhaps Volusianus could have led the Roman army. It’s a risky proposition, based on his interpretation of the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, the tombstones of the auxiliary cavalrymen from Apamea (some of whose deaths are dated to the year of the joint consulship of Trebonianus Gallus and Volusianus, which happened from January 252 CE to January 253 CE), and the

antoniniani issued by the mint of Antioch with legend

ADVENTUS AVGG on their reverse, which he thinks must’ve responded to a real arrival of one of the two

augusti in Syria. As I said it’s a risky hypothesis as it’s not backed by any documentary source, and Potter’s dating is not supported by most scholars. I’ll return to this issue later.

Satellite image of the environs of Barbalissos in modern times (Google Maps).

If the battle took place in the environs of Barbalissos, unless the Romans had prepared field works to strengthen their position (as they were fighting a defensive battle), they were at a clear disadvantage. They would’ve been facing south, and the most logical thing would’ve been to anchor their left flank on the Euphrates’ riverbank. But unless they had built fixed defenses, that left their right flank dangerously exposed; as Barbalissos was not fortified, in case of defeat the town would have not been a viable refuge, which means that again, unless the Romans had built a fortified camp, in case of defeat they would’ve been exposed to a pursuit by an enemy which was superior in cavalry; and that was a potential recipe for disaster (it was just what destroyed Crassus’ army after Carrhae, for it suffered most of its losses during the retreat and not during the battle itself).

As I wrote before, Šābuhr I’s army possibly had superiority in numbers, but I should make a precision here. In theory, both Romans and Sasanians could mobilize armies of more than 100,000 men and the eastern expeditions of Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Severus Alexander and Gordian III had involved numbers far larger than that. But it’s highly improbable that they concentrated at a single place such large armies. Ancient sources give lower numbers for single armies, which in the most extreme cases oscillated between 60,000 and 80,000 men tops, which seems to have been the absolute maximum number, probably due to logistical issues. For the Sasanian empire in the VI century CE, the maximum attested number of forces in Mesopotamia happened under Xusrō I, when two armies operated simultaneously; one of 70,000 men and another of 20,000 men. If the Roman army numbered 60,000 men then Šābuhr I’s army must’ve oscillated between that amount and 70,000-80,000 men maximum, especially considering that he would’ve been forced to leave many detachments behind him to block bypassed Roman fortresses and towns and protect his supply lines. Possibly he enjoyed numerical superiority, but not an overwhelming one.

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to say that the Romans should’ve chosen another place to fight, but by this point of time the Roman command had probably lost its nerves. Barbalissos is located 260 km upstream from the southernmost Roman outpost on the Euphrates (Dura Europos) and 380 km upstream from Anatha, the southernmost Palmyrene outpost located on an island in the Euphrates. At Barbalissos, the Sasanian army had left the Syrian desert behind and could turn west from the river and advance along the Roman road to Chalcis (120 km from Barbalissos) across fertile countryside, from where it could’ve menaced Antioch to the west, Apamea and southern Syria to the south and Beroia and the rich and populous region of Cyrrhestica to the north. Barbalissos was the last spot where the Romans could stop Šābuhr I’s army with minimal damage to the rich Roman provinces of Syria Coele and Syria Phoenicia. Probably the Roman commanders felt that this was their last opportunity to avoid an unmitigated disaster.

A feature of Arsacid and Sasanian armies that differentiated them starkly from Roman ones is their dependence of a reduced number of elite fighters, the noble

asvārān that came from the ranks of the

wuzurgān and the

āzādagān /

āzādān. This heavy cavalry was a formidable fighting force, formed by men who were professional warriors, expensively equipped and who trained for war since childhood. Due to their very expensive equipment and life-long training, massive losses amongst their ranks were impossible to replace on a short amount of time and had serious (possibly even destabilizing) social effects, because the

asvārān were not only soldiers, but the very governing elite of the empire. Also, because of the strict social order of Iranian society, belonging to the

asvārān was strictly reserved to the

wuzurgān and

āzādān; other social groups were banned from joining its ranks, even if they had the economic resources to pay for the equipment and horse.

British reenactor Nadeem Ahmad wearing the arms and armour of a III century CE Partho-Sasanian heavy cavalryman. The helmet is based on the famous Dura Europos helmet.

These elite noble

asvārān were formidable multi-purpose fighters, and Persian and Arab chroniclers have left ample testimony of their fighting abilities. But what surfaces from all these testimonies is how small their numbers were: as a young man, Šābuhr II led a force of 1,000 elite

asvārān deep into Arabia which smashed all opposition in front of them, Bahrām V Gūr defeated soundly the Hephtalites with a force of 5,000 elite

asvārān, and Bahrām Čōbīn defeated the Turks with a force of 7,000

asvārān. But despite their effectiveness and flamboyancy, the dependence over such forces was a serious weakness for the Arsacid and Sasanian empires. Huge losses among the

asvārān were just unacceptable: they were a blow to the Iranian social fabric, and as they affected the dangerous Iranian nobility they could lead to discontent amongst the

wuzurgān, always a very bad development for any Iranian king. Some scholars have suggested that the changes in the composition and tactics of Sasanian armies were partly due to this fact, as the extensive use of

asvārān charges by Arsacid armies against Roman infantry would’ve been very costly for this elite force.

Now, the armies of Šābuhr I employed also infantry of three types:

payghan soldiers (peasants conscripted into the army as cannon fodder, servants and sappers), mercenary units made of specific ethnic groups (traditionally Gilanis, Daylamites and other tribal groups within the Iranian plateau, but now also probably forces recruited in the Caucasus,

Kušanšahr and even India) and especially the elite infantry archers, specialized in area shooting to which the massed ranks of Roman infantry were particularly vulnerable. To this, one should add the extensive use of mercenary and allied cavalry: nomadic Iranian tribes, Armenians, Iberians, Albanians, Kushans, Central Asian tribes, etc. And perhaps for the first time, also elephants (we know that Šābuhr I employed them, but we don’t know if they were present at Barbalissos) and a sizeable siege train (a giant battering ram employed against the gates of Antioch by Šābuhr I’s army was still surviving in the IV century and was reported by Ammianus Marcellinus).

Detailed view of the equipment worn by reenactor Nadeem Ahmad in the above picture.

Although much more heterogeneous and less cohesive than the Roman army, such an army was much more flexible in its tactical possibilities and if led by a competent commander (which Šābuhr I certainly was) against a cowered or incompetently led Roman army, it had good odds at succeeding in a field battle.

Barbalissos was according to the ŠKZ an unabated disaster for the Roman army, which was mostly annihilated. Due to this, to the numbers involved and to the devastation of one of the richest areas of the Roman empire, Barbalissos was a far worse defeat that Abritus, and ranks in the same league as Cannae, Arausio or Carrhae in the list of Roman military disasters. Scholars agree that in this instance the ŠKZ’s account is entirely believable, for both Greek and Latin sources and archaeology confirm that Syria was utterly devastated by a foreign invasion at this time, including some cities which held legionary garrisons, which hints that said legions had been all but wiped out at the disaster. In my opinion, a disaster of such magnitude could have unfolded in two possible ways:

- If the Romans fought (as I wrote above) with a linear deployment and their left flank anchored on the Euphrates, Sasanian cavalry could have bypassed their exposed right flank and then proceeded to surround the army; after being surrounded the Roman army would’ve been massacred, but such a battle would’ve come at a high cost to the Sasanian army for the Romans would’ve fought to the last man in a closed formation, which was their strongest battle ability.

- Another possibility is that the Roman army broke ranks and fled at a given point in the battle, and in the open countryside around Barbalissos with no fortresses nearby this would have led to the Roman army being massacred by the pursuing Sasanian cavalry (just like it had happened to Crassus’ army).

Both possibilities would have led to the virtual annihilation of the Roman army, with the second one being cheaper in manpower losses to Šābuhr I.

Now, I’ll address briefly the alternative reconstruction of events proposed by David S. Potter. He construes verses 117-130 of the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle as referring to Mareades, the Antiochene magistrate (and not to Iotapianus, like Hartmann supports) and implying that somehow this Mareades would have gathered an armed following and led an armed campaign (or acts of banditry) in Cappadocia. This is solely based on Potter’s interpretation of the aforementioned passage of the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, and according to Potter the failure of this campaign would have led to Mareades’ flight to Sasanian territory. The key difference though is chronological: Potter dates Šābuhr I’s offensive to the summer of 252 CE, based on Antiochene

antoniniani (with their

ADVENTUS AVGG legends), the order of events in the

Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle and Zosimus (both mention the Sasanian raids

before Aemilianus’ usurpation) and the tombstones for Apamea; in this chronology he’s supported by Jean-Charles Balty, who also places the Sasanian invasion in 252 CE, although to other scholars it’s doubtful if a bunch of gravestones is enough evidence, for these stones don’t even describe how did these cavalrymen die, they could’ve died in a skirmish, due to an epidemic or to other causes, and not necessarily fighting against Šābuhr I’s great invasion.

And then there’s the issue of linking these events with the ones that were taking place in Europe. If the Roman disaster at Barbalissos happened in 252 CE, then it would’ve been a further reason for the success of Aemilianus’ revolt; but it would be strange that the German and Raetian armies would have been still willing to support Trebonianus Gallus if his military reputation had been so utterly humiliated (on another side, it’s worth remembering that the Italian army that accompanied him promptly changed sides at Interamna and sided with Aemilianus).

On the other side, if the invasion took place in 253 CE, then the situation changes, because the battle of Barbalissos would’ve happened almost simultaneously to Aemilianus’ usurpation, meaning that the Roman eastern army would’ve been left to its own devices while there was yet another Roman civil war in Europe.

Another factor are the resumed Gothic raids, some of which (the ones by land across the Danube) were repelled by Aemilianus. If these raids were unprovoked and undertaken by the Goths as a breach of the 251 CE treaty, and happened in late 252 CE or early 253 CE (just before Aemilianus’ revolt), they could have been an opportunistic reaction by the Goths to the news of the new Roman disaster in the East (just like Abritus would have been an encouragement to Šābuhr I). In my opinion, this could lend further support to Potter’s thesis.