I love this aar as much as the HOI2 one. Just finished it. Good job as always Tommy!

Through Rivers of Blood and Mountains of Gold - The Story of The House of D'Albon

- Thread starter Tommy4ever

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Pope uses the title Vicar of Christ.

Vice-Gerent of Christ was a title used by the Eastern Roman Emperors.

Vice-Gerent of Christ was a title used by the Eastern Roman Emperors.

Amaury, The Mighty (Part 2)

Lived: 1339-1394

Head of House of D’Albon: 1353-1394

Latin Emperor: 1353-1394

Roman Emperor: 1381-1394

Vice Gerent of Christ: 1359-1394

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria and Araby: 1353-1394

King of the Armenians: 1373-1394

King of Africa: 1378-1394

King of Croatia 1381-1394

King of Babylon: 1393-1394

With the end of the Pact of God early in his reign during the 1370s Amaury aimed to improve relations with the other major power of the Mediterranean – Sicily. In the constituent Latin Kingdoms if Italy, Sicily and Africa a new, very separate, branch of the D’Albons had formed since the division of Alderic I’s Empire. Here the D’Albons had adapted to Italian culture and by 1370 had adopted the local name for D’Albons former the Di Albano ‘clan’. Strangely the primary D’Albon line had bred much more thoroughly with the Di Albanos than they had with their fellow Frankish D’Albons in the far West of the Empire. In Sicily and Italy the rulers were still closely related cousins of Amaury and thus when the Emperor requested an alliance with the Sicilians it was quickly signed off.

In 1377, barely two years after the alliance was agreed, Sicily got Jerusalem involved in one of the frequent wars amongst the Di Albanos. This conflict was one that clearly depicted the intertwined nature of the families in the Mediterranean part of the Empire. Henriette D’Albon was the eldest child of Amaury. She was also the niece of the King of Italy and was betrothed to Donato King of Sicily. However on the very night she was supposed to be married to Donato King Antonio of Africa (a close cousin of both her and Donato) stole her away in a strangely Homoresque action. However Antonio failed to learn the lessons of Paris all those Centuries before and quickly the scorned King Donato of Sicily went to his Imperial cousin in Jerusalem for help. Amaury, equally enraged at his daughter’s betrayal, agreed to marshal the armies of Jerusalem and into a war of vengeance against the tiny Kingdom of Africa.

The initial phase of the war saw the Sicilian African levies crushed by Antonio and his armies in the passes of the Tunisian highlands. After this the King of Africa simply waited for the inevitable Imperial assault. When it came in mid 1378 he was shocked at it scale. A huge fleet, carrying as many as 60,000-70,000 men arrived off of Malta. There the regionally powerful African fleet (which had up to then stopped Sicilian forces from crossing from Europe) was utterly annihilated. Shortly later the huge army began to land all around the Kingdom’s coast. Antonio decided to surrender himself, his army and Henriette rather than fight a doomed battle. In exchange for letting Amaury annex Africa and seize the crown the Imperial Generals handed both Antonio and Henriette over to Donato. If the chroniclers are to be believed (and they were rarely kind to Donato) he beat Henriette to death, forcing Antonio to watch as he did so, before having the former King of Africa tortured to death in Palermo’s dungeons.

Yet peace would be only short lived. Only a few months after the conclusion of the War in Africa Emperor Konstantinos Lakarikis, the very man who had crushed the Bulgar and Aqba Khan in the Great Crusade, effectively condemned the Greek state to oblivion by invading the Patriarchal Kingdom of Croatia in November 1378. By the end of the year he had forced the Patriarch of Croatia into exile and crowned himself King of Croatia. In response Donato King of Sicily went to war in Spring 1379.

Konstantinos invaded Southern Italy with nearly ¼ of a million men. Donato managed to muster around 120,000 in opposition and marched to meet at some of the Roman army. However after landing his host at Bari the Emperor had quickly sent a large contingent into the Southern Apennine Mountains.

Whilst travelling across the mountains from Naples Donato’s army was ambushed and all but destroyed. Barely ¼ of the original Sicilian army escaped.

By August 1379 all that remained of Sicilian Southern Italy was the city of Foggia. Here the 18,000 man remnants of Donato’s army had managed to beat back several much larger Roman attacks. It was at this time that the King of Sicily again sent a desperate cry for help to his Imperial cousin in Jerusalem. Amaury quickly assembled a mighty army from every part of his Jerusalem and in October declared war.

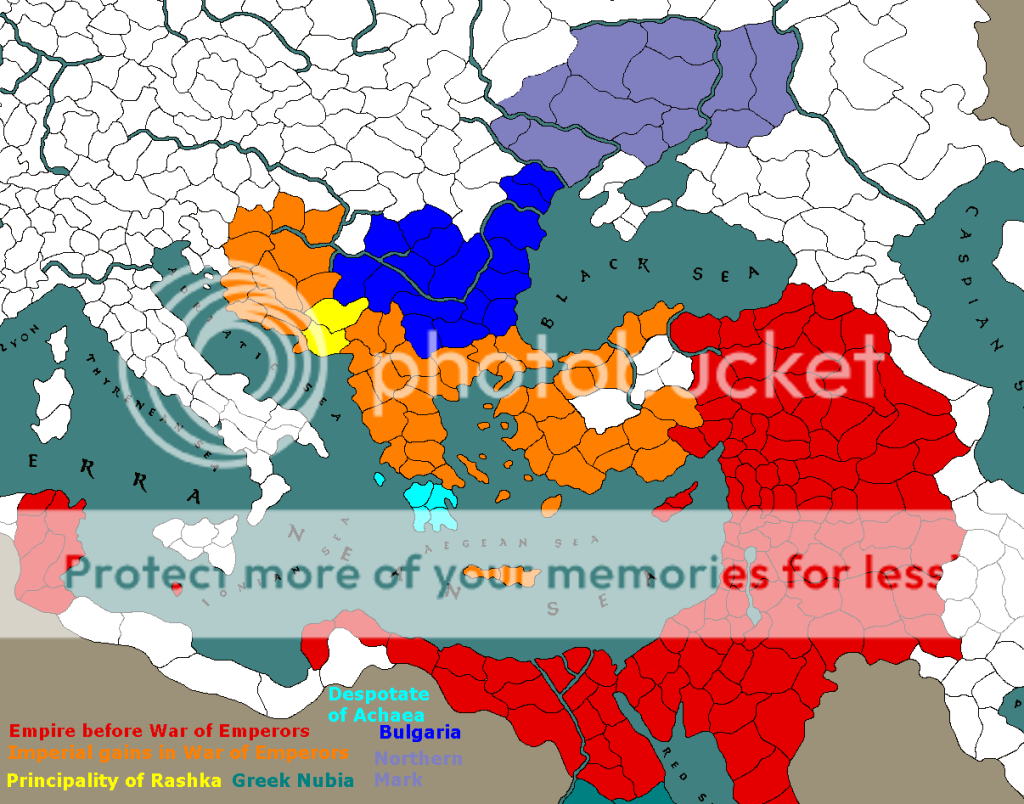

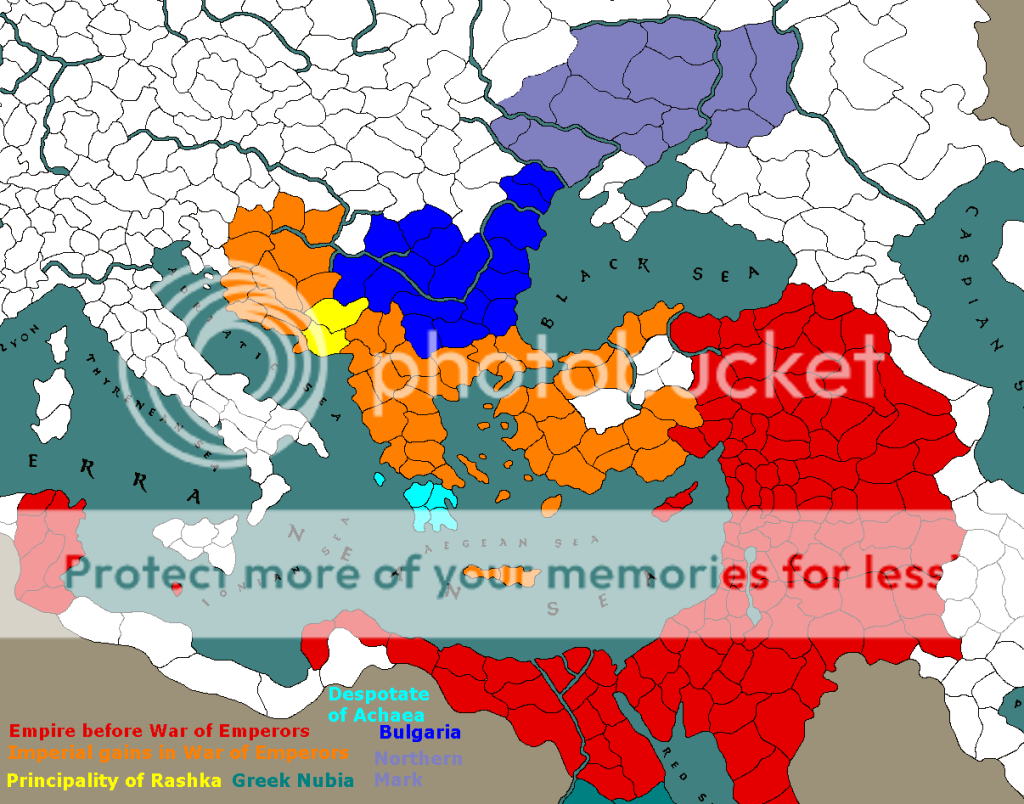

When Amaury invaded in October 1379 the Roman Empire virtually empty of warriors with so many men in Italy. This allowed Jerusalem to seize all of Anatolia, Thrace and Greece proper as well as placing the Queen of Cities under siege (the siege was led by Amaury personally). This forced Konstantinos to abandon his dream of reconquering Italy for the Romans in favour of protecting the Greeks from Latin invasion. Out of the initial army of ¼ of a million there were around 150,000 survivors. 50,000 Greeks were left in Italy to try to hold onto the Roman gains there whilst Konstantinos led 60,000 ashore at Dyrrachion with the remaining 40,000 being dispersed to other fronts in the Balkans. Just in shore from Dyrrachion the one and only major battle of the War of Emperors took place at Orchid.

Many people claim that the Battle of Orchid was the beginning of the end of the Medieval period. Not only did bring about the collapse of the Greek Roman Empire but it also ended the old methods of warfare which had been in place since the Dark Ages. For Centuries heavily armed cavalry had been an unstoppable force, whilst Eastern style horse archers may have been able to severely batter a heavy cavalry charge there was nothing on earth that could stop one. That was until the Battle of Orchid.

Richard Jimenez Duke of Oultrejordan was a military genius and an innovator of his age. Whilst almost every army at this time (even other Jerusalemer armies) still relied on the large contingents of heavily armoured knights Richard had very few. Instead he equipped his well paid and trained infantry with great pikes. At the Battle of Orchid the Roman Emperor had a very large force of mighty Cataphracts with large numbers of infantry levies in support. Meanwhile Jimenez had around 1/3 of the number of men in the Emperor’s 60,000 man force and little to no cavalry. Instead his army was mostly made up of the new pike regiments with a smattering of heavily armoured swordsmen on foot.

Seeing the supposed weakness of the Jimenz’ force Konstantinos charged down on the Duke’s army at the head of several thousand Cataphracts. However rather than buckle and break under the Emperor’s pressure the pikemen stood firm. The cavalry charge was utterly broken and as the broken Greek force tried to turn back and flee Jimenez unleashed his swordsmen to cut down the prime of the Roman army. The Emperor barely escaped with his life. Following this the levy infantry of the Romans charged but was cut down by the much better trained and equipped Latin force.

Mere days after news reached Constantinople of the shocking reverse the city threw open its gates to Amaury on the promise that the city would not be harmed. For the rest of the war the seemingly dazed and confused Byzantine armies would march from defeat to defeat, often against much smaller and supposedly weaker armies. On March 3rd Bari, the last Roman stronghold in Italy, fell. By June everything Roman South of the Danube was in Latin hands. On July 19th Konstantinos surrendered his Imperial tile, the Kingship of Croatia, Constantinople, Anatolia, Croatia and much of Greece to Amaury. Within months 3 Greek successor states would form.

Amaury’s gains in the war were huge in both territory and prestige as he became the world’s first ever double-Emperor. Meanwhile the Greek territories he did not annex quickly divided into several successor nations. In Nubia a Greek elite crowned themselves Kings of the former theme. In the Northern colonies Alexios Komnenos (one of the last of his dynasty) made himself Prince of the Northern Mark. In the only recently conquered Principality of Rashka the local Serbs rose up to reform the independent Principality of Rashka. Meanwhile Konstantinos Lakarikis (the former Emperor) became King of Bulgaria with his son ruling the Despotate of Achaea as his nominal vassal.

For the rest of his reign discontent would simmer angrily throughout the vast Empire ruled over by Amaury with many minor rebellions (including many in Greece) but nothing too threatening breaking out across the realm. Meanwhile in this period the Empire slowly expanded. In 1383, for reasons still unclear, the Patriarch of Croatia (no longer equivalent to a King but now back in control of his old lands) called upon his flock to take the last Pagan outpost in the known world – the Canaries. The Canary islands had long been ‘officially’ ruled by many different Islamic states of North Africa but never had their overlords been able to exert any real control over the islands and so they retained their Shamanist religion. During the conflicts in the Mediterranean the King of Zenata had given up his claim to the islands, allowing them to rule themselves. So in 1383 the Patriarch himself sailed to the islands to take them for his own Holy See. In 1389 the Archbishop of Tripoli (by now surrounded by Amaury’s nation) decided to swear allegiance to his Emperor, giving up his self determination. Then between 1392 and 1393 Amaury had his second son Louis led an expedition against the crumbling Seljuk Empire which ended in great success.

Then, sensationally, upon the return of Louis from Persia the dying Emperor became the first and only ever D’Albon to stray from Primogeniture when he declared Louis his rightful heir, shunning his older son Philippe who had led a failed rebellion in the 1380s and been generally incompetent. On Christmas Day 1393 crowned himself King of Babylon and just two weeks later passed away peacefully. His son would leave Jerusalem for the comfort and opulence of Constantinople, the primary line of D’Albons would never again rule from the Holy City.

Lived: 1339-1394

Head of House of D’Albon: 1353-1394

Latin Emperor: 1353-1394

Roman Emperor: 1381-1394

Vice Gerent of Christ: 1359-1394

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria and Araby: 1353-1394

King of the Armenians: 1373-1394

King of Africa: 1378-1394

King of Croatia 1381-1394

King of Babylon: 1393-1394

With the end of the Pact of God early in his reign during the 1370s Amaury aimed to improve relations with the other major power of the Mediterranean – Sicily. In the constituent Latin Kingdoms if Italy, Sicily and Africa a new, very separate, branch of the D’Albons had formed since the division of Alderic I’s Empire. Here the D’Albons had adapted to Italian culture and by 1370 had adopted the local name for D’Albons former the Di Albano ‘clan’. Strangely the primary D’Albon line had bred much more thoroughly with the Di Albanos than they had with their fellow Frankish D’Albons in the far West of the Empire. In Sicily and Italy the rulers were still closely related cousins of Amaury and thus when the Emperor requested an alliance with the Sicilians it was quickly signed off.

In 1377, barely two years after the alliance was agreed, Sicily got Jerusalem involved in one of the frequent wars amongst the Di Albanos. This conflict was one that clearly depicted the intertwined nature of the families in the Mediterranean part of the Empire. Henriette D’Albon was the eldest child of Amaury. She was also the niece of the King of Italy and was betrothed to Donato King of Sicily. However on the very night she was supposed to be married to Donato King Antonio of Africa (a close cousin of both her and Donato) stole her away in a strangely Homoresque action. However Antonio failed to learn the lessons of Paris all those Centuries before and quickly the scorned King Donato of Sicily went to his Imperial cousin in Jerusalem for help. Amaury, equally enraged at his daughter’s betrayal, agreed to marshal the armies of Jerusalem and into a war of vengeance against the tiny Kingdom of Africa.

The initial phase of the war saw the Sicilian African levies crushed by Antonio and his armies in the passes of the Tunisian highlands. After this the King of Africa simply waited for the inevitable Imperial assault. When it came in mid 1378 he was shocked at it scale. A huge fleet, carrying as many as 60,000-70,000 men arrived off of Malta. There the regionally powerful African fleet (which had up to then stopped Sicilian forces from crossing from Europe) was utterly annihilated. Shortly later the huge army began to land all around the Kingdom’s coast. Antonio decided to surrender himself, his army and Henriette rather than fight a doomed battle. In exchange for letting Amaury annex Africa and seize the crown the Imperial Generals handed both Antonio and Henriette over to Donato. If the chroniclers are to be believed (and they were rarely kind to Donato) he beat Henriette to death, forcing Antonio to watch as he did so, before having the former King of Africa tortured to death in Palermo’s dungeons.

Yet peace would be only short lived. Only a few months after the conclusion of the War in Africa Emperor Konstantinos Lakarikis, the very man who had crushed the Bulgar and Aqba Khan in the Great Crusade, effectively condemned the Greek state to oblivion by invading the Patriarchal Kingdom of Croatia in November 1378. By the end of the year he had forced the Patriarch of Croatia into exile and crowned himself King of Croatia. In response Donato King of Sicily went to war in Spring 1379.

Konstantinos invaded Southern Italy with nearly ¼ of a million men. Donato managed to muster around 120,000 in opposition and marched to meet at some of the Roman army. However after landing his host at Bari the Emperor had quickly sent a large contingent into the Southern Apennine Mountains.

Whilst travelling across the mountains from Naples Donato’s army was ambushed and all but destroyed. Barely ¼ of the original Sicilian army escaped.

By August 1379 all that remained of Sicilian Southern Italy was the city of Foggia. Here the 18,000 man remnants of Donato’s army had managed to beat back several much larger Roman attacks. It was at this time that the King of Sicily again sent a desperate cry for help to his Imperial cousin in Jerusalem. Amaury quickly assembled a mighty army from every part of his Jerusalem and in October declared war.

When Amaury invaded in October 1379 the Roman Empire virtually empty of warriors with so many men in Italy. This allowed Jerusalem to seize all of Anatolia, Thrace and Greece proper as well as placing the Queen of Cities under siege (the siege was led by Amaury personally). This forced Konstantinos to abandon his dream of reconquering Italy for the Romans in favour of protecting the Greeks from Latin invasion. Out of the initial army of ¼ of a million there were around 150,000 survivors. 50,000 Greeks were left in Italy to try to hold onto the Roman gains there whilst Konstantinos led 60,000 ashore at Dyrrachion with the remaining 40,000 being dispersed to other fronts in the Balkans. Just in shore from Dyrrachion the one and only major battle of the War of Emperors took place at Orchid.

Many people claim that the Battle of Orchid was the beginning of the end of the Medieval period. Not only did bring about the collapse of the Greek Roman Empire but it also ended the old methods of warfare which had been in place since the Dark Ages. For Centuries heavily armed cavalry had been an unstoppable force, whilst Eastern style horse archers may have been able to severely batter a heavy cavalry charge there was nothing on earth that could stop one. That was until the Battle of Orchid.

Richard Jimenez Duke of Oultrejordan was a military genius and an innovator of his age. Whilst almost every army at this time (even other Jerusalemer armies) still relied on the large contingents of heavily armoured knights Richard had very few. Instead he equipped his well paid and trained infantry with great pikes. At the Battle of Orchid the Roman Emperor had a very large force of mighty Cataphracts with large numbers of infantry levies in support. Meanwhile Jimenez had around 1/3 of the number of men in the Emperor’s 60,000 man force and little to no cavalry. Instead his army was mostly made up of the new pike regiments with a smattering of heavily armoured swordsmen on foot.

Seeing the supposed weakness of the Jimenz’ force Konstantinos charged down on the Duke’s army at the head of several thousand Cataphracts. However rather than buckle and break under the Emperor’s pressure the pikemen stood firm. The cavalry charge was utterly broken and as the broken Greek force tried to turn back and flee Jimenez unleashed his swordsmen to cut down the prime of the Roman army. The Emperor barely escaped with his life. Following this the levy infantry of the Romans charged but was cut down by the much better trained and equipped Latin force.

Mere days after news reached Constantinople of the shocking reverse the city threw open its gates to Amaury on the promise that the city would not be harmed. For the rest of the war the seemingly dazed and confused Byzantine armies would march from defeat to defeat, often against much smaller and supposedly weaker armies. On March 3rd Bari, the last Roman stronghold in Italy, fell. By June everything Roman South of the Danube was in Latin hands. On July 19th Konstantinos surrendered his Imperial tile, the Kingship of Croatia, Constantinople, Anatolia, Croatia and much of Greece to Amaury. Within months 3 Greek successor states would form.

Amaury’s gains in the war were huge in both territory and prestige as he became the world’s first ever double-Emperor. Meanwhile the Greek territories he did not annex quickly divided into several successor nations. In Nubia a Greek elite crowned themselves Kings of the former theme. In the Northern colonies Alexios Komnenos (one of the last of his dynasty) made himself Prince of the Northern Mark. In the only recently conquered Principality of Rashka the local Serbs rose up to reform the independent Principality of Rashka. Meanwhile Konstantinos Lakarikis (the former Emperor) became King of Bulgaria with his son ruling the Despotate of Achaea as his nominal vassal.

For the rest of his reign discontent would simmer angrily throughout the vast Empire ruled over by Amaury with many minor rebellions (including many in Greece) but nothing too threatening breaking out across the realm. Meanwhile in this period the Empire slowly expanded. In 1383, for reasons still unclear, the Patriarch of Croatia (no longer equivalent to a King but now back in control of his old lands) called upon his flock to take the last Pagan outpost in the known world – the Canaries. The Canary islands had long been ‘officially’ ruled by many different Islamic states of North Africa but never had their overlords been able to exert any real control over the islands and so they retained their Shamanist religion. During the conflicts in the Mediterranean the King of Zenata had given up his claim to the islands, allowing them to rule themselves. So in 1383 the Patriarch himself sailed to the islands to take them for his own Holy See. In 1389 the Archbishop of Tripoli (by now surrounded by Amaury’s nation) decided to swear allegiance to his Emperor, giving up his self determination. Then between 1392 and 1393 Amaury had his second son Louis led an expedition against the crumbling Seljuk Empire which ended in great success.

Then, sensationally, upon the return of Louis from Persia the dying Emperor became the first and only ever D’Albon to stray from Primogeniture when he declared Louis his rightful heir, shunning his older son Philippe who had led a failed rebellion in the 1380s and been generally incompetent. On Christmas Day 1393 crowned himself King of Babylon and just two weeks later passed away peacefully. His son would leave Jerusalem for the comfort and opulence of Constantinople, the primary line of D’Albons would never again rule from the Holy City.

Last edited:

NOOOOO!!!

Oh well- now we have the Albanos (Albanoi plural) dynasty going Greek and ruling the City of Constantine. Convert to Orthodox!!! Or merge Latin/Orthodox churches!

Oh well- now we have the Albanos (Albanoi plural) dynasty going Greek and ruling the City of Constantine. Convert to Orthodox!!! Or merge Latin/Orthodox churches!

Vicegerent or vice-regent, I don't really know actually, lol.

Gotta check in some dictionary, I cannot trust the internet.

What the fuck did you do?

o:wacko:

o:wacko:

Recreate the Roman Empire?

Change tag to BYZ?

Really epic.

Gotta check in some dictionary, I cannot trust the internet.

What the fuck did you do?

Recreate the Roman Empire?

Change tag to BYZ?

Really epic.

Hannibal X: I'm afraid just as in OT Orthodoxy will have to cling on in Russia, even there its has to battle with the large Muslim populations left over from the Bulgar Empire. However unlike OT many of the Greeks will convert. By the end of the AAR I'd say Greece was perhaps 40-60% Latin (excluding Constantinople whose huge, mainly Latin, population would skew things).

Enewald: The rest of the game will see me try to unite the Roman Empire, plus some additions.

When Amaury got old I gave Byz to Louis, loaded as Louis then auto-killed Amaury allowing me to change my tag to Byzantines (this is the same thing I did to become Jerusalem).

(this is the same thing I did to become Jerusalem).

There are both in game and human reasons for doing this:

1. The only good colour to paint the world is purple

2. I love the Byzantines and the Romans

3. I love Konstantinopolis

4. Roman Empire gets to own twice as much land without penalty

5. I'll be taking many more lands to the West so the Queen of Cities is more central

EDIT: As a side note as we are getting to the end of this AAR here are the updates I currently plan

Sum up of Jerusalem residency

King 1

World in 1400

King 2

King 3

King 4

World in 1475 (I will make up stuff for 1453-1475 as this goes to the end of a reign)

Sum up of residency in Byzantium up to 1475

Sum up of AAR

MABYE - world from 1475 to present in one update. Unlikely though.

Enewald: The rest of the game will see me try to unite the Roman Empire, plus some additions.

When Amaury got old I gave Byz to Louis, loaded as Louis then auto-killed Amaury allowing me to change my tag to Byzantines

There are both in game and human reasons for doing this:

1. The only good colour to paint the world is purple

2. I love the Byzantines and the Romans

3. I love Konstantinopolis

4. Roman Empire gets to own twice as much land without penalty

5. I'll be taking many more lands to the West so the Queen of Cities is more central

EDIT: As a side note as we are getting to the end of this AAR here are the updates I currently plan

Sum up of Jerusalem residency

King 1

World in 1400

King 2

King 3

King 4

World in 1475 (I will make up stuff for 1453-1475 as this goes to the end of a reign)

Sum up of residency in Byzantium up to 1475

Sum up of AAR

MABYE - world from 1475 to present in one update. Unlikely though.

Last edited:

Interim

The D’Albon Residency in Jerusalem

Philippe, The Good (ruled 1281-1310)

Achievements:

• Held new Empire together

• Turned Jerusalem into a regional power

• Helped form unique Latin-Outremer Culture (sometimes called Franco-Arabic)

• King of Syria in 1299

• Won wars against both Egypt and Medina

Pros:

• Talented statesman and General

• Tolerant – Fought off Papal Inquisitor

• Established Jerusalem’s power

• Respected around the world

Cons:

• D’Albon Germany fell under his Imperial Rule

• Failed to stop or intervene in D’Albon Civil War (France vs Burgundy and Italy)

• Left major problems in succession

Robert, The Bastard (ruled 1310-1314)

Achievements:

• Manage to rise to throne despite being an illegitimate son of a whore

• Became first King of Araby upon succession

Pros:

• Kept Philippe’s line from dying out and kept D’Albon seat of power in East

Cons:

• Untalented

• Illegitimate son of a whore

• Civil Strife

Alderic, The Reformer (ruled 1314-1350)

Achievements:

• Founded Latin Church

• Founded Latin Empire

• King f Egypt in 1327

• Survived Black Death

• Formed Pact of God

• Conquered Egypt and defeated Seljuks in Anatolia

Pros:

• Bold

• Stood up to Pope and reformed the rotten institution that was the Catholic Church (within his Empire)

• Turned Jerusalem into a major and wealthy power

• Great statesman

Cons:

• Engineered the Great Western Schism that would divide Christianity a second time

• Aggressive

• Persecuted many clergy who did not accept Schism

Hugues, The Wrathful (ruled 1350-1353)

Achievements:

• Conquered and destroyed Emirate of Medina

Pros:

• Great Warrior King

• Defeated Jerusalem’s last Arab rival

• Won many battles in both war with Medina and Civil War

Cons:

• Rape of Mecca led directly to Civil War

• Unpopular – Civil War

• Intolerant

• Defeated in Civil War

Amaury, The Mighty (ruled 1353-1394)

Achievements:

• Vice Gerent of Christ from 1359

• King of the Armenians form 1373

• King of Africa from 1378

• King of Croatia from 1381

• King of Babylon from 1393

• First D’Albon Roman Emperor from 1381

• Conquered huge tracts of land

• Made his Empire the only (known) world superpower

Pros:

• Medieval Warfare started to be replaced during his reign (cannons at Antioch in Civil war and pikemen at Orchid in War of Emperors)

• Tried to end Schism

• Gave responsibilities to talented men

• Loyal to allies – fought for Sicilian pride against Africa and fought to save Latin Empire against Romans

• Replaced Abbasid Caliph with a converted Christian Patriarch (Caliph was forced to convert and become Patriarch)

Cons:

• Civil strife under his reign (after his meeting with Pope and after War of Emperors)

• Lacked talents

• Destroyed Byzantine (Hellenistic Roman) Empire

• Ended Abbasid Caliphate

The D’Albon Residency in Jerusalem

Philippe, The Good (ruled 1281-1310)

Achievements:

• Held new Empire together

• Turned Jerusalem into a regional power

• Helped form unique Latin-Outremer Culture (sometimes called Franco-Arabic)

• King of Syria in 1299

• Won wars against both Egypt and Medina

Pros:

• Talented statesman and General

• Tolerant – Fought off Papal Inquisitor

• Established Jerusalem’s power

• Respected around the world

Cons:

• D’Albon Germany fell under his Imperial Rule

• Failed to stop or intervene in D’Albon Civil War (France vs Burgundy and Italy)

• Left major problems in succession

Robert, The Bastard (ruled 1310-1314)

Achievements:

• Manage to rise to throne despite being an illegitimate son of a whore

• Became first King of Araby upon succession

Pros:

• Kept Philippe’s line from dying out and kept D’Albon seat of power in East

Cons:

• Untalented

• Illegitimate son of a whore

• Civil Strife

Alderic, The Reformer (ruled 1314-1350)

Achievements:

• Founded Latin Church

• Founded Latin Empire

• King f Egypt in 1327

• Survived Black Death

• Formed Pact of God

• Conquered Egypt and defeated Seljuks in Anatolia

Pros:

• Bold

• Stood up to Pope and reformed the rotten institution that was the Catholic Church (within his Empire)

• Turned Jerusalem into a major and wealthy power

• Great statesman

Cons:

• Engineered the Great Western Schism that would divide Christianity a second time

• Aggressive

• Persecuted many clergy who did not accept Schism

Hugues, The Wrathful (ruled 1350-1353)

Achievements:

• Conquered and destroyed Emirate of Medina

Pros:

• Great Warrior King

• Defeated Jerusalem’s last Arab rival

• Won many battles in both war with Medina and Civil War

Cons:

• Rape of Mecca led directly to Civil War

• Unpopular – Civil War

• Intolerant

• Defeated in Civil War

Amaury, The Mighty (ruled 1353-1394)

Achievements:

• Vice Gerent of Christ from 1359

• King of the Armenians form 1373

• King of Africa from 1378

• King of Croatia from 1381

• King of Babylon from 1393

• First D’Albon Roman Emperor from 1381

• Conquered huge tracts of land

• Made his Empire the only (known) world superpower

Pros:

• Medieval Warfare started to be replaced during his reign (cannons at Antioch in Civil war and pikemen at Orchid in War of Emperors)

• Tried to end Schism

• Gave responsibilities to talented men

• Loyal to allies – fought for Sicilian pride against Africa and fought to save Latin Empire against Romans

• Replaced Abbasid Caliph with a converted Christian Patriarch (Caliph was forced to convert and become Patriarch)

Cons:

• Civil strife under his reign (after his meeting with Pope and after War of Emperors)

• Lacked talents

• Destroyed Byzantine (Hellenistic Roman) Empire

• Ended Abbasid Caliphate

And another d'Albon dynasty. Lets hope for Europe they are somewhat more sane than the Habsburgs...

Louis, The Tormented

Lived: 1362-1400

Head of House of D’Albon: 1394-1400

Roman Emperor: 1394-1400

Latin Emperor: 1394-1400

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria, Arab, Babylon, Croatia, Africa and the Armenians:1394-1400

Louis’ short and turbulent reign left a lasting mark upon world history. Louis moved his capital to Constantinople, abandoning Jerusalem which for a century had been the seat of D’Albon Imperial power. Following Amaury’s destruction of the Hellenistic Roman Empire (commonly called the Byzantine Empire in modern texts) in 1381 the Empire had ‘officially’ become the successor of Rome with the Roman Imperial title passing to the then Latin Emperor. However the so called 5th Empire was not truly founded until Louis’ succession in 1394 when the new Latin speaking Roman Empire came into being.

Just as Louis was being invested with his multitude of titles in the new capital in 1394 his elder brother, shunned in the succession by their father, was amassing an army around the old capital in Jerusalem. Here, after he and a group of nobles stormed the city, Philippe was able to force the Patriarch of Jerusalem to invest him with all the titles of his father (using mock crowns in replace of the real ones in Constantinople). Immediately after the ceremonies in Constantinople were over Louis amassed a relatively small army consisting mostly of the pikemen with smaller elements of a traditional Latin Christian army and sailed for Judea.

At the Battle of Ascalon Louis’ pikes would come up against the heavy cavalry of his brother. Philippe had struggled to form an army to push through his claim due to a lack of support and a lack of funds, the majority of his army consisted of hot headed young landless knights who had been promised fiefs in exchange for military service. The Battle of Ascalon was relatively short but utterly decisive. Philippe charged with his cavalry against Louis’ pikes, both he and most of his cavalry were slaughtered by his brother’s men and within a few hours most of his army simply fled without Louis’ men having to launch a counter charge.

Sadly during Louis’ absence a rather small scale outbreak of plague ravished Constantinople. The Imperial family was hit very hard with Louis’ mother, wife, two of his daughter and most importantly the eldest of his two sons killed in the disaster. After hearing the news Louis fell into a deep depression that would last for the rest of his life. He would never remarry or indeed lay with another woman following the death of his wife and decided to send his son away as he reminded him too much of the ones he had lost.

In early 1395 Louis commissioned a small team of dedicated scribes to write up the history of his illustrious family. The so called D’Alboniad (a nickname given to the work by modern historians) remains the most comprehensive history of any Medieval family ever created and was one of the main sources of information for this history.

Believing that the new Emperor was weak due to his legendary bouts of depression (Louis was known not to rise from his bed for days) Konstantinos (the former Roman Emperor who had defeated Aqba Khan and the Bulgars before being crushed by the Latins) started to launch periodic raids on Imperial Greece from his bases in Bulgaria and encouraged his son to do the same from Achaea. Eventually the frustration of these minor attacks became too much and Louis decided to marshal his armies for war.

The Imperial army vastly outnumbered the forces of the Greeks and within a few short months the Greeks were all but broken. In a last ditched attempt to save his state from ruin Konstantinos led 15,000 men out to face Louis’ own 19,000 man army near the Bulgarian capital of Tyrnovo.

Louis set his army up in the fashion that had become the norm for Latin armies, with a well trained and equipped pike wall standing as the frontline. Louis, knowing that it was his opponent who needed a decisive victory and not him simply waited for the Greeks to come.

Yet the Greeks had discovered a relatively effective counter to the Latin pike walls – longbows. These fearsome bows imported from Catholic England could fire over great distances and packed a considerable punch, yet the Greeks had only small contingents of longbow men and were thus unable to use them extensively enough to counter the Latins. Konstantinos’ tactic was to send a large force of powerful swordsmen to march forward, accompanied by the longbowmen who would batter the pike formations and try to break them up for the Greek swordsmen to attack. The tactic seemed to be very effective as the Latin pike wall quickly began to falter under intense bombardment as the Greek infantry drew closer. Just as the Greeks began to come dangerously close to the Latin lines Louis unleashed his own secret weapon.

Although cannons had become an essential part of any major siegeing army in Europe gunpowder had yet to make a major impact on battles fought on the open field. That was before Tyrnovo. With the Greeks getting ever closer to the Latin lines suddenly several thousand gun wielding soldiers emerged from behind the pike wall and as one they unleashed a volley of gunfire against the Greeks. Although, according to primary sources, the guns were not nearly as deadly as the longbows they caused extreme terror and confusion within the Greek advance. After a second volley was fired upon the Greeks the swordsmen began to turn and flee and at this moment Louis unleashed his cavalry. The Greek army was run down and utterly crushed but the Roman Emperor was badly wounded in the charge after he sustained a wound to his face. Louis would never recover his sight and within a few weeks he was totally blind.

Despite utterly crushing the Greeks Louis let them off with only a light peace treaty in which Achaea and Corfu were surrendered. It seems that following his personal disaster at Tyrnovo the Emperor had gone back into another bout of depression and felt no desire to continue to the conflict.

Three months after returning to Constantinople Louis hung himself in his bedchamber leaving the Empire in the hands of his 20 year old son Gauthier a man who would greatly expand the Empire, although unlike his predecessor’s war would not be his most potent tool.

Lived: 1362-1400

Head of House of D’Albon: 1394-1400

Roman Emperor: 1394-1400

Latin Emperor: 1394-1400

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria, Arab, Babylon, Croatia, Africa and the Armenians:1394-1400

Louis’ short and turbulent reign left a lasting mark upon world history. Louis moved his capital to Constantinople, abandoning Jerusalem which for a century had been the seat of D’Albon Imperial power. Following Amaury’s destruction of the Hellenistic Roman Empire (commonly called the Byzantine Empire in modern texts) in 1381 the Empire had ‘officially’ become the successor of Rome with the Roman Imperial title passing to the then Latin Emperor. However the so called 5th Empire was not truly founded until Louis’ succession in 1394 when the new Latin speaking Roman Empire came into being.

Just as Louis was being invested with his multitude of titles in the new capital in 1394 his elder brother, shunned in the succession by their father, was amassing an army around the old capital in Jerusalem. Here, after he and a group of nobles stormed the city, Philippe was able to force the Patriarch of Jerusalem to invest him with all the titles of his father (using mock crowns in replace of the real ones in Constantinople). Immediately after the ceremonies in Constantinople were over Louis amassed a relatively small army consisting mostly of the pikemen with smaller elements of a traditional Latin Christian army and sailed for Judea.

At the Battle of Ascalon Louis’ pikes would come up against the heavy cavalry of his brother. Philippe had struggled to form an army to push through his claim due to a lack of support and a lack of funds, the majority of his army consisted of hot headed young landless knights who had been promised fiefs in exchange for military service. The Battle of Ascalon was relatively short but utterly decisive. Philippe charged with his cavalry against Louis’ pikes, both he and most of his cavalry were slaughtered by his brother’s men and within a few hours most of his army simply fled without Louis’ men having to launch a counter charge.

Sadly during Louis’ absence a rather small scale outbreak of plague ravished Constantinople. The Imperial family was hit very hard with Louis’ mother, wife, two of his daughter and most importantly the eldest of his two sons killed in the disaster. After hearing the news Louis fell into a deep depression that would last for the rest of his life. He would never remarry or indeed lay with another woman following the death of his wife and decided to send his son away as he reminded him too much of the ones he had lost.

In early 1395 Louis commissioned a small team of dedicated scribes to write up the history of his illustrious family. The so called D’Alboniad (a nickname given to the work by modern historians) remains the most comprehensive history of any Medieval family ever created and was one of the main sources of information for this history.

Believing that the new Emperor was weak due to his legendary bouts of depression (Louis was known not to rise from his bed for days) Konstantinos (the former Roman Emperor who had defeated Aqba Khan and the Bulgars before being crushed by the Latins) started to launch periodic raids on Imperial Greece from his bases in Bulgaria and encouraged his son to do the same from Achaea. Eventually the frustration of these minor attacks became too much and Louis decided to marshal his armies for war.

The Imperial army vastly outnumbered the forces of the Greeks and within a few short months the Greeks were all but broken. In a last ditched attempt to save his state from ruin Konstantinos led 15,000 men out to face Louis’ own 19,000 man army near the Bulgarian capital of Tyrnovo.

Louis set his army up in the fashion that had become the norm for Latin armies, with a well trained and equipped pike wall standing as the frontline. Louis, knowing that it was his opponent who needed a decisive victory and not him simply waited for the Greeks to come.

Yet the Greeks had discovered a relatively effective counter to the Latin pike walls – longbows. These fearsome bows imported from Catholic England could fire over great distances and packed a considerable punch, yet the Greeks had only small contingents of longbow men and were thus unable to use them extensively enough to counter the Latins. Konstantinos’ tactic was to send a large force of powerful swordsmen to march forward, accompanied by the longbowmen who would batter the pike formations and try to break them up for the Greek swordsmen to attack. The tactic seemed to be very effective as the Latin pike wall quickly began to falter under intense bombardment as the Greek infantry drew closer. Just as the Greeks began to come dangerously close to the Latin lines Louis unleashed his own secret weapon.

Although cannons had become an essential part of any major siegeing army in Europe gunpowder had yet to make a major impact on battles fought on the open field. That was before Tyrnovo. With the Greeks getting ever closer to the Latin lines suddenly several thousand gun wielding soldiers emerged from behind the pike wall and as one they unleashed a volley of gunfire against the Greeks. Although, according to primary sources, the guns were not nearly as deadly as the longbows they caused extreme terror and confusion within the Greek advance. After a second volley was fired upon the Greeks the swordsmen began to turn and flee and at this moment Louis unleashed his cavalry. The Greek army was run down and utterly crushed but the Roman Emperor was badly wounded in the charge after he sustained a wound to his face. Louis would never recover his sight and within a few weeks he was totally blind.

Despite utterly crushing the Greeks Louis let them off with only a light peace treaty in which Achaea and Corfu were surrendered. It seems that following his personal disaster at Tyrnovo the Emperor had gone back into another bout of depression and felt no desire to continue to the conflict.

Three months after returning to Constantinople Louis hung himself in his bedchamber leaving the Empire in the hands of his 20 year old son Gauthier a man who would greatly expand the Empire, although unlike his predecessor’s war would not be his most potent tool.

Good update once again. However guess it will be one of the last. Looking forward to where the new Roman Empire will expand.

By this stage there is not a single country on earth that can match the new Roman Empire. The last 70 years of this AAR (53 of which are in game) will be an orgy of expansionism as I look to restore Rome's borders. There shall be much inheriting and much conquering.

Also to answer a question Enewald put awhile back this won't be going into EUIII which is probably my least favourite of all my Paradox games.

Also to answer a question Enewald put awhile back this won't be going into EUIII which is probably my least favourite of all my Paradox games.

Interim

World in 1400

1. Emirate of Granada

2. Principality of Pommeralia

3. Principality of Rashka

4. Khanate of Crimea

5. Emirate of Georgia

Spain, France and Morocco

Following its conversion from Islam to Latin Christianity the Kingdom of Zenata continued to fight not only with the Latin nations of Barcelona, Sicily and France but also with the last few remnants of Al-Andus in Granada. Yet, spectacularly, in 1383 the King signed a treaty with the Latin states in which it submitted to the Latin Emperor and joined the Empire in exchange for all of France’s lands in Spain and the title Despot of all the Spanish on top of the thrones of all the now destroyed Spanish Kingdoms. In truth this deal was actually very beneficial to the French who had been struggling to hold on to their rebellious lands in Spain due to the constant conflicts between the Western states of the Latin Empire and the Pope’s powerful German ally. The Duchies of Brittany and Gascony managed to take advantage of the struggles of their master and broke away from France. In Morocco the English firmly established themselves and used their large African holdings as a base from which Catholic missionaries could compete with Latin ones for the souls of the Moroccans who were quickly converting away from Islam.

The Catholic World

At the height of the Turkish invasions half of Ireland, all of Poland, all of Bohemia and much of Germany was ruled by the Turk. However a coalition of Catholic states featuring the Papacy, Prussia Hungary, Germany and most significantly England turned back the tide and by 1400 the last Turkish outposts in the West had fallen. Meanwhile in the year 1373 the Abdul line of Scottish Kings came to an end leaving the Fitzgeralds of England to take the Scots throne and form a British nation. By 1400 England had emerged as a real power as Kings of England, Scotland, Poland and Wales.

Red – Latin Christian

Dark Red – Mixed Latin and Muslim

Purple – Mixed Latin and Orthodox

Blue – Roman Catholic Christian

Dark Blue – Mixed Latin and Catholic

Orange – Orthodox

Green – Muslim

In terms of religious adherents the greatest loser of the 14th Century was Islam. Beaten back to a small corner of Southern Spain, removed from Africa, forced from Anatolia and much of Armenia and Mesopotamia, pushed back in Russia and Poland. By 1400 Islam was without a Caliph (after the forced conversion of the Abbasids) and worse still; in India large scale Hindu rebellions had forced to Muslims back to their core territories around the Indus after they had previously sought to dominate the whole subcontinent. Back in Europe Latin Christianity was starting to replace the traditional Orthodox Church in many areas of the Empire but the majority of Greeks retained the Greek rites.

World in 1400

1. Emirate of Granada

2. Principality of Pommeralia

3. Principality of Rashka

4. Khanate of Crimea

5. Emirate of Georgia

Spain, France and Morocco

Following its conversion from Islam to Latin Christianity the Kingdom of Zenata continued to fight not only with the Latin nations of Barcelona, Sicily and France but also with the last few remnants of Al-Andus in Granada. Yet, spectacularly, in 1383 the King signed a treaty with the Latin states in which it submitted to the Latin Emperor and joined the Empire in exchange for all of France’s lands in Spain and the title Despot of all the Spanish on top of the thrones of all the now destroyed Spanish Kingdoms. In truth this deal was actually very beneficial to the French who had been struggling to hold on to their rebellious lands in Spain due to the constant conflicts between the Western states of the Latin Empire and the Pope’s powerful German ally. The Duchies of Brittany and Gascony managed to take advantage of the struggles of their master and broke away from France. In Morocco the English firmly established themselves and used their large African holdings as a base from which Catholic missionaries could compete with Latin ones for the souls of the Moroccans who were quickly converting away from Islam.

The Catholic World

At the height of the Turkish invasions half of Ireland, all of Poland, all of Bohemia and much of Germany was ruled by the Turk. However a coalition of Catholic states featuring the Papacy, Prussia Hungary, Germany and most significantly England turned back the tide and by 1400 the last Turkish outposts in the West had fallen. Meanwhile in the year 1373 the Abdul line of Scottish Kings came to an end leaving the Fitzgeralds of England to take the Scots throne and form a British nation. By 1400 England had emerged as a real power as Kings of England, Scotland, Poland and Wales.

Red – Latin Christian

Dark Red – Mixed Latin and Muslim

Purple – Mixed Latin and Orthodox

Blue – Roman Catholic Christian

Dark Blue – Mixed Latin and Catholic

Orange – Orthodox

Green – Muslim

In terms of religious adherents the greatest loser of the 14th Century was Islam. Beaten back to a small corner of Southern Spain, removed from Africa, forced from Anatolia and much of Armenia and Mesopotamia, pushed back in Russia and Poland. By 1400 Islam was without a Caliph (after the forced conversion of the Abbasids) and worse still; in India large scale Hindu rebellions had forced to Muslims back to their core territories around the Indus after they had previously sought to dominate the whole subcontinent. Back in Europe Latin Christianity was starting to replace the traditional Orthodox Church in many areas of the Empire but the majority of Greeks retained the Greek rites.

Interesting world you have there, even if its full of the usual CK-anomalies as a Christian Zenata or the pope ruling Ireland  . Nice looking empite by the way...

. Nice looking empite by the way...

There are still Muslims from Mali to Somalia in Africa?

Islam has been beaten nicely.

Islam has been beaten nicely.

What a wonderful AAR! Fun, well written interesting, and filled with great Monarchs.

I award you the most (well highly ) coveted prize in AARland, a genuine Lord Strange Cookie of British Awesomeness ●

) coveted prize in AARland, a genuine Lord Strange Cookie of British Awesomeness ●

This is only awarded to AARs I have read, enjoyed, and that should be read by any avid AAR reader. Good job!

I award you the most (well highly

This is only awarded to AARs I have read, enjoyed, and that should be read by any avid AAR reader. Good job!

Lord Strange: thank you for awarding me with what is the most prestigious of all AAR cookies  . I hope you will continue to enjoy the last few updates of this AAR.

. I hope you will continue to enjoy the last few updates of this AAR.

Enewald: Yeah, I must have forgot about them. o. I'd imagine that with such great reverses in Europe, North Africa and the Near East Muslim expansion would be more focussed on Sub-Saharan Africa so there would probably be very large Muslim population south of Timbuktu

o. I'd imagine that with such great reverses in Europe, North Africa and the Near East Muslim expansion would be more focussed on Sub-Saharan Africa so there would probably be very large Muslim population south of Timbuktu

FlyingDutchie: I love things like Christian Zenata as well. The story of the conversion is particularily amazing: the de Semurs (remnants of English Crusaders in Spain) were defeated by Zenata and found their way into the Zenata nobility. Eventually they somehow got a marriage with one of the King's daughters and managed to inherit having retained their faith for more than one generation. Then within a rather short time (in game) the majority of the Muslim country shifted over to Christian along with most of the nobles.

Also the Empire is only going to get better looking

Enewald: Yeah, I must have forgot about them.

FlyingDutchie: I love things like Christian Zenata as well. The story of the conversion is particularily amazing: the de Semurs (remnants of English Crusaders in Spain) were defeated by Zenata and found their way into the Zenata nobility. Eventually they somehow got a marriage with one of the King's daughters and managed to inherit having retained their faith for more than one generation. Then within a rather short time (in game) the majority of the Muslim country shifted over to Christian along with most of the nobles.

Also the Empire is only going to get better looking

Gauthier, The Magnificent Lech

Lived: 1380-1431

Head of House of D’Albon: 1400-1431

Roman Emperor: 1400-1431

Latin Emperor: 1400-1427

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria, Arab, Babylon, Croatia, Africa and the Armenians: 1400-1431

King of Serbia: 1405-1431

King of Sicily: 1406-1431

King of Bulgaria: 1411-1431

King of Italy: 1419-1431

King of Germany: 1424-1431

Gauthier was the world’s third and last ‘Double Emperor’ due to his abolition of the Latin Empire in 1427. Yet what he is most well known for is his infamous personal life. His affairs were sordid, at times revolting, yet Gauthier’s inbreeding program proved extremely beneficial to the Roman Empire as it brought all of Italy under Imperial control without a single battle. Under Gauthier’s reign Rome went secured a greater level of expansionism than had been seen for more than the Empire had seen for more than a thousand years, his conquests both military and personal greatly expanded his state’s border and made the Roman Empire the primary power in the West as well as the only power in the East.

Generations of inbreeding finally came to a head for the Sicilian Di Albanos with a weak and broken generation that ruled around Gauthier’s early reign. King Stefano had had 5 children: Vincenzo (who died as a babe), Sante (who became King as a teenager), Magadelena, Brunhilde and Silverstro. In 1402 Gauthier took King Sante’s eldest sister Magadelena as his bride. However she had already been stricken in an outbreak of the plague and on top of that suffered from severe learning difficulties which left her in a near child like state. Although he had organised the marriage himself Gauthier seemed unwilling to go ahead with the union when he finally saw the near-dead figure of his betrothed on their wedding day. He is reported to have asked his Chancellor, and close friend, Simone Rurik if there was any way to call off the marriage. Simone’s response was to advise his friend to simply ‘’close your eyes and think of Rome’’. It was a mantra that would help propel Gauthier’s loins to greatness. Incredibly, in spite of her diseased nature Gauthier was able to conceive a child with Magadelena within a month of their marriage. Sadly however the plague managed to take her before she could give birth to her child. Shortly after Magadelena’s demise King Sante commited suicide leaving his mentally disabled brother Silverstro to inherit the throne of Sicily. Around the same time Gauthier arranged a marriage between himself and the younger daughter of the last Sicilian Di Albano generation – Brunhilde. At the time Brunhilde was just 14 so the marriage itself did not take place until her 16th birthday in 1403. Brunhilde, whilst free of disease, was physically repulsive. She had a hunchback, 6 fingers on her left hand, walked with a limp and had a shrivelled right arm. Yet somehow Gauthier managed to impregnate her and in 1404 Aimone D’Albon was born. This birth was great news for the Sicilian nobility who were becoming increasingly worried about King Silverstro. In appears that the simple King slowly began to lose his mind and by 1404 was repeatedly making rash proclamations, demanding wars and executions without cause. Seeing a chance to ‘steady the boat’ and increase their own power through a regency council the Sicilian nobility had the King quietly ‘dealt with’ as he was sent off to a remote monastery and invited the newborn Aimone to the Sicilian throne. Back in the Empire, immediately after she gave birth to Aimone Brunhilde was exiled to Thessalonica as Gauthier refused to spend another moment in her presence. With her entire family taken from her Brunhilde hung herself over the Winter of 1404.

Gauthier then immediately married the eldest of 8 daughters of the great King Napoleon of Italy. Napoleon had been unfortunate enough to have 8 daughters and no sons, now already in his 50s it seemed clear that any child between Gauthier and his daughter Constance would stand to inherit his rich realm. Constance herself, like most good D’Albon girls, suffered from the effects of inbreeding brought on by promiscuity between her older, closely related, family members. However unlike Brunhilde Constance was a true beauty however she had the mind of a young child. Nether the less Gauthier was quickly able to impregnate her. By the end of the year Geruad was born and the following year Constance gave birth to Isabella. At the time Italy was involved in yet another war with the Germans as once again a Germany army had crossed the Alps to invade Napoleon’s Kingdom. Napoleon had fought off countless German invasions in the past but in the latest attack, although his army secured victory on the field, Napoleon was killed and baby Geruad rose to the Italian throne.

One year after Geruad’s ascension to the Italian throne and Gauthier’s eldest, Aimone, was taken by a nasty bout of pneumonia. Gauthier then inherited his son’s realm.

Roman territorial expansion in Gauthier’s early reign proceeded at great pace. In 1405 Rashka swore allegiance to the Empire, this not only united Croatia by land with the rest of the Empire but allowed Gauthier to crown himself King of Serbia. Meanwhile in 1411 Gauthier led a large army in an invasion of Bulgaria. The legendary former Emperor Konstantinos Lakarikis (now 72 years old) was finally killed in this war after being obliterated by a cannon shot whilst defending Tyrnovo. At the end of the conflict all of Bulgaria South of the Danube was ceded. Konstantinos’ line would continue to rule over the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldova, eventually crowning themselves Kings of Romania.

In 1419 Germany started the last of dozens of wars between the Western D’Albon states as the mighty Teutonic Kingdom that had been raging since the late 13th Century. Early in the war Geruad, King of Italy was killed whilst travelling between Venice and Genoa, this left Gauthier with the Kingdom of Italy and the Roman Emperor quickly made peace. With only France and Holland standing against them the German von Frankens were in a good position. The war continued until 1421 and the French suffered a bad defeat. The Netherlands were finally and completely occupied by Germany and the King of France was killed. However no French territory was actually lost to the Germans. But the disastrous effects of the bloody conflict on the King’s armed forced meant the King was utterly incapable of holding on to Southern France which rose up in rebellion against him. Between 1421 and 1423 several small and newly independent Counties and Bishoprics swore allegiance to the Roman Emperor allowing for Roman expansion into France.

Back in Germany the von Frankens and the loyal German nobles of the West of the realm were exhausted by the conflict with France and severely weakened. Just as soon as the truce between France and Germany was sealed in 1421 Germany erupted in Civil War. The von Bocksburgs, at the head of a confederation of Eastern lords, wereable to overthrow the von Frankens and crown themselves Kings in 1423. However whilst the von Frankens ruled a large and powerful demesne along the Rhine the von Bocksburgs merely ruled in Austria and Bavaria. Seeing a golden opportunity to reclaim Germany for the D’Albons in 1423 Gauthier marched to war in Germany.

The war itself was incredibly one sided. The von Bocksburgs were weak and very unpopular outside of the East of the Empire, indeed much of Germany welcomed the Roman armies with open arms and switched sides to fight against their fellow Germans. When the von Bocksburg armies were able to face up to the Roman they were crushed as the much larger, more modern and better trained Imperial armies waltzed from victory to victory. In just 7 months the most powerful Catholic Kingdom was in the hands of a Latin Christian Emperor.

After the fall of Germany Gauthier started to make overtures to the last states of the Latin Empire (France, Zenata/Spain, Barcelona and the states in Southern France) hoping to bring these Western nations into a unified Empire. In response to this Zenata/Spain in 1425 and France in 1427 chose to abandon the Latin Empire. Seeing no reason to continue the Empire’s tradition Gauthier abolished the Latin Empire in 1427 and transferred all the previous powers of the title of Latin Emperor to the title of Roman Emperor.

Throughout Gauthier’s life he kept up an illicit and highly sinful relationship with his married sister Adela. Over the course of 18 years Gauthier sired 3 children by his sister – Henri (1405), Richard (1415) and Robert (1423). All of whom he scandalously allowed to stay in court alongside his legitimate children and a fourth bastard (Geofrey born 1415). After his affairs with the Di Albano Princess were over Gauthier continued to attempt to place more of his children on foreign thrones. Between 1408 and 1419 Gauthier was married to Joanna Fitzgerald (the eldest child of the King of England) despite the deformities of his bride Gauthier had 6 children by Joanna and through this relationship he made sure of his son and heir Raymond’s claim to the English throne. After Joanna’s death Gauthier married Margret Arpad (3rd daughter of the King of Hungary. Sadly their marriage was cut short in 1422 after Margret became ill and died. After this Gauthier settled down with Alienor D’Albon, his dream cousin. Alienor and Gauthier shared a grandfather and were dangerously close in relation yet she was a famous beauty and after 2 decades of serving his country in his bedchamber Gauthier felt it was best to reward himself for all his exertions.

In 1427 Gauthier was badly wounded in a hunting accident and for the last few years of his reign he battled with an ever worsening illness before eventually succumbing to his wounds.

Over the course of his life Gauthier had 15 ligitimate children, 6 wives, 4 (known illegitimate) and 1 (known) long term mistress who also happened to be his sister. He certainly deserves the ‘’magnificent lech’’ moniker history has granted him. Upon his death in 1431 he left all his lands to Raymond, his oldest surviving son, who was also first in line to the English throne.

Lived: 1380-1431

Head of House of D’Albon: 1400-1431

Roman Emperor: 1400-1431

Latin Emperor: 1400-1427

King of Jerusalem, Egypt, Syria, Arab, Babylon, Croatia, Africa and the Armenians: 1400-1431

King of Serbia: 1405-1431

King of Sicily: 1406-1431

King of Bulgaria: 1411-1431

King of Italy: 1419-1431

King of Germany: 1424-1431

Gauthier was the world’s third and last ‘Double Emperor’ due to his abolition of the Latin Empire in 1427. Yet what he is most well known for is his infamous personal life. His affairs were sordid, at times revolting, yet Gauthier’s inbreeding program proved extremely beneficial to the Roman Empire as it brought all of Italy under Imperial control without a single battle. Under Gauthier’s reign Rome went secured a greater level of expansionism than had been seen for more than the Empire had seen for more than a thousand years, his conquests both military and personal greatly expanded his state’s border and made the Roman Empire the primary power in the West as well as the only power in the East.

Generations of inbreeding finally came to a head for the Sicilian Di Albanos with a weak and broken generation that ruled around Gauthier’s early reign. King Stefano had had 5 children: Vincenzo (who died as a babe), Sante (who became King as a teenager), Magadelena, Brunhilde and Silverstro. In 1402 Gauthier took King Sante’s eldest sister Magadelena as his bride. However she had already been stricken in an outbreak of the plague and on top of that suffered from severe learning difficulties which left her in a near child like state. Although he had organised the marriage himself Gauthier seemed unwilling to go ahead with the union when he finally saw the near-dead figure of his betrothed on their wedding day. He is reported to have asked his Chancellor, and close friend, Simone Rurik if there was any way to call off the marriage. Simone’s response was to advise his friend to simply ‘’close your eyes and think of Rome’’. It was a mantra that would help propel Gauthier’s loins to greatness. Incredibly, in spite of her diseased nature Gauthier was able to conceive a child with Magadelena within a month of their marriage. Sadly however the plague managed to take her before she could give birth to her child. Shortly after Magadelena’s demise King Sante commited suicide leaving his mentally disabled brother Silverstro to inherit the throne of Sicily. Around the same time Gauthier arranged a marriage between himself and the younger daughter of the last Sicilian Di Albano generation – Brunhilde. At the time Brunhilde was just 14 so the marriage itself did not take place until her 16th birthday in 1403. Brunhilde, whilst free of disease, was physically repulsive. She had a hunchback, 6 fingers on her left hand, walked with a limp and had a shrivelled right arm. Yet somehow Gauthier managed to impregnate her and in 1404 Aimone D’Albon was born. This birth was great news for the Sicilian nobility who were becoming increasingly worried about King Silverstro. In appears that the simple King slowly began to lose his mind and by 1404 was repeatedly making rash proclamations, demanding wars and executions without cause. Seeing a chance to ‘steady the boat’ and increase their own power through a regency council the Sicilian nobility had the King quietly ‘dealt with’ as he was sent off to a remote monastery and invited the newborn Aimone to the Sicilian throne. Back in the Empire, immediately after she gave birth to Aimone Brunhilde was exiled to Thessalonica as Gauthier refused to spend another moment in her presence. With her entire family taken from her Brunhilde hung herself over the Winter of 1404.

Gauthier then immediately married the eldest of 8 daughters of the great King Napoleon of Italy. Napoleon had been unfortunate enough to have 8 daughters and no sons, now already in his 50s it seemed clear that any child between Gauthier and his daughter Constance would stand to inherit his rich realm. Constance herself, like most good D’Albon girls, suffered from the effects of inbreeding brought on by promiscuity between her older, closely related, family members. However unlike Brunhilde Constance was a true beauty however she had the mind of a young child. Nether the less Gauthier was quickly able to impregnate her. By the end of the year Geruad was born and the following year Constance gave birth to Isabella. At the time Italy was involved in yet another war with the Germans as once again a Germany army had crossed the Alps to invade Napoleon’s Kingdom. Napoleon had fought off countless German invasions in the past but in the latest attack, although his army secured victory on the field, Napoleon was killed and baby Geruad rose to the Italian throne.

One year after Geruad’s ascension to the Italian throne and Gauthier’s eldest, Aimone, was taken by a nasty bout of pneumonia. Gauthier then inherited his son’s realm.

Roman territorial expansion in Gauthier’s early reign proceeded at great pace. In 1405 Rashka swore allegiance to the Empire, this not only united Croatia by land with the rest of the Empire but allowed Gauthier to crown himself King of Serbia. Meanwhile in 1411 Gauthier led a large army in an invasion of Bulgaria. The legendary former Emperor Konstantinos Lakarikis (now 72 years old) was finally killed in this war after being obliterated by a cannon shot whilst defending Tyrnovo. At the end of the conflict all of Bulgaria South of the Danube was ceded. Konstantinos’ line would continue to rule over the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldova, eventually crowning themselves Kings of Romania.

In 1419 Germany started the last of dozens of wars between the Western D’Albon states as the mighty Teutonic Kingdom that had been raging since the late 13th Century. Early in the war Geruad, King of Italy was killed whilst travelling between Venice and Genoa, this left Gauthier with the Kingdom of Italy and the Roman Emperor quickly made peace. With only France and Holland standing against them the German von Frankens were in a good position. The war continued until 1421 and the French suffered a bad defeat. The Netherlands were finally and completely occupied by Germany and the King of France was killed. However no French territory was actually lost to the Germans. But the disastrous effects of the bloody conflict on the King’s armed forced meant the King was utterly incapable of holding on to Southern France which rose up in rebellion against him. Between 1421 and 1423 several small and newly independent Counties and Bishoprics swore allegiance to the Roman Emperor allowing for Roman expansion into France.

Back in Germany the von Frankens and the loyal German nobles of the West of the realm were exhausted by the conflict with France and severely weakened. Just as soon as the truce between France and Germany was sealed in 1421 Germany erupted in Civil War. The von Bocksburgs, at the head of a confederation of Eastern lords, wereable to overthrow the von Frankens and crown themselves Kings in 1423. However whilst the von Frankens ruled a large and powerful demesne along the Rhine the von Bocksburgs merely ruled in Austria and Bavaria. Seeing a golden opportunity to reclaim Germany for the D’Albons in 1423 Gauthier marched to war in Germany.

The war itself was incredibly one sided. The von Bocksburgs were weak and very unpopular outside of the East of the Empire, indeed much of Germany welcomed the Roman armies with open arms and switched sides to fight against their fellow Germans. When the von Bocksburg armies were able to face up to the Roman they were crushed as the much larger, more modern and better trained Imperial armies waltzed from victory to victory. In just 7 months the most powerful Catholic Kingdom was in the hands of a Latin Christian Emperor.

After the fall of Germany Gauthier started to make overtures to the last states of the Latin Empire (France, Zenata/Spain, Barcelona and the states in Southern France) hoping to bring these Western nations into a unified Empire. In response to this Zenata/Spain in 1425 and France in 1427 chose to abandon the Latin Empire. Seeing no reason to continue the Empire’s tradition Gauthier abolished the Latin Empire in 1427 and transferred all the previous powers of the title of Latin Emperor to the title of Roman Emperor.

Throughout Gauthier’s life he kept up an illicit and highly sinful relationship with his married sister Adela. Over the course of 18 years Gauthier sired 3 children by his sister – Henri (1405), Richard (1415) and Robert (1423). All of whom he scandalously allowed to stay in court alongside his legitimate children and a fourth bastard (Geofrey born 1415). After his affairs with the Di Albano Princess were over Gauthier continued to attempt to place more of his children on foreign thrones. Between 1408 and 1419 Gauthier was married to Joanna Fitzgerald (the eldest child of the King of England) despite the deformities of his bride Gauthier had 6 children by Joanna and through this relationship he made sure of his son and heir Raymond’s claim to the English throne. After Joanna’s death Gauthier married Margret Arpad (3rd daughter of the King of Hungary. Sadly their marriage was cut short in 1422 after Margret became ill and died. After this Gauthier settled down with Alienor D’Albon, his dream cousin. Alienor and Gauthier shared a grandfather and were dangerously close in relation yet she was a famous beauty and after 2 decades of serving his country in his bedchamber Gauthier felt it was best to reward himself for all his exertions.

In 1427 Gauthier was badly wounded in a hunting accident and for the last few years of his reign he battled with an ever worsening illness before eventually succumbing to his wounds.

Over the course of his life Gauthier had 15 ligitimate children, 6 wives, 4 (known illegitimate) and 1 (known) long term mistress who also happened to be his sister. He certainly deserves the ‘’magnificent lech’’ moniker history has granted him. Upon his death in 1431 he left all his lands to Raymond, his oldest surviving son, who was also first in line to the English throne.