PROLOGUE

A wedding, a funeral, and a rebirth

A wedding, a funeral, and a rebirth

On February 3, 1112, Duchess Gerberga of Provence lay dying in Arles. With her death, the Bosonid dynasty will pass into history, and an uncertain future awaits Provence. The Bosonids they were the first Provencal nobility to rule in Provence, which had been used as a bargaining chip between Italian, Frankish, and German interests for centuries. Now it appeared Provence would again find itself under foreign rule. Gerberga, unlike her ancestors, would pick whose rule that would be, however.

The Shield of House of Barcelona-Bosonid

Gerberga's father, Jaufret, had died with one son and four daughters. His son, Betran II, ruled for twenty years and had two wives, but only managed one illegitimate daughter, Cecile. When Betran died, there was a qualified male heir. Adelais, Jaufret's oldest daughter, had been married to Provence's endlessly agitating neighbor, the Duke of Toulouse. Adelais's only son could claim the Duchy of Provence. The Bosonids closed ranks to prevent this from happening. In 1032, the Duke of Toulouse – due to a similar situation – had already usurped the Margravate of Provence, the traditional title of the Dukes, and was only prevented from taking over the Duchy itself by a cousin line of the family seizing power. Not willing to see their Duchy subsumed by their arch-enemy so easily, the family handlers overlooked the children of Jaufret's second daughter, Etiennette – Etiennette was already dead, and though she had a surviving son, he was widely considered an idiot. Gerberga, Jaufret's last surviving child and third daughter, became Duchess of Provence.

Gerberga was naïve but she had a strong ally that ensured the Duke of Toulouse would not act against her succession – Aicard of Marseilles. Aicard, the most powerful Archbishop in Provence, had been removed from power by the Pope, on paper anyway, at the request of Betran. Aicard was widely popular, however, and the people of Marseilles, the clergy in Aix, and virtually all of the Provencal nobility aside from Betran, wrote the Pope in support of Aicard. The Vatican held firm, so long as Betran requested Aicard remain excommunicated, and when Urban II visited Provence in 1095 to sing the laurels of Crusade, he even had to avoid places loyal to Aicard to prevent an uncomfortable confrontation. Gerberga did not find Aicard as threatening as her father, and in promising him a return to official status and revocation of his excommunication, she asked for his support. Aicard granted it, and with the most influential clergyman in Provence advocating for her, the upstart nephew in Toulouse backed down. Aicard returned to power, the Pope embraced the Archbishop at Gerberga's request, and thenceforth Aicard was indispensable to the Duchess.

Gerberga and her husband, Gilbert the Count of Gevaudan, had only one daughter, Dolca. In 1111, the 21-year-old Dolca remained unmarried, and with Gerberga in her 50s, the Bosonids were eager to see the girl find a good match, but there was a problem. The Duke of Toulouse, liege of the Count of Gevaudan, had used his power over Gilbert to request that any groom to Dolca – also heir to the County of Gevaudan – be approved by him. Several good candidates had been rejected by the Duke for superfluous reasons. The Duke, no doubt, hoped to gain Provence again by forcing Dolca to become a spinster and forcing the inheritance to revert to him or his progeny.

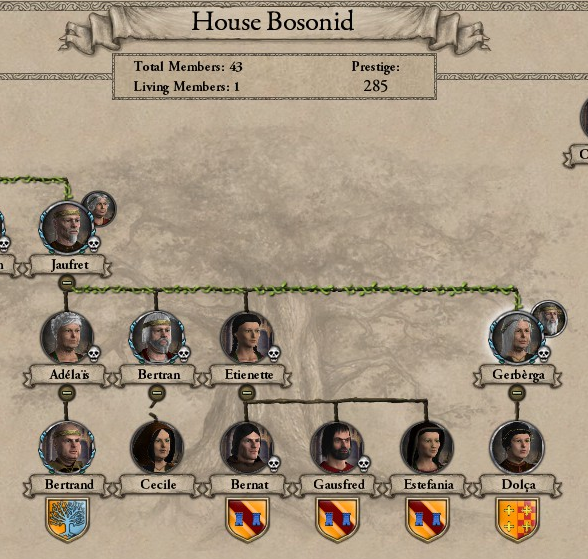

House de Bosonid, 1112, about to be deceased

Aicard, ever helpful, finally nominated a very old friend. Due to the conspiracies of his uncle and regent, the teenage Ramon Berenguer III of Barcelona was de facto in exile from his own realm until 1097. He traveled extensively in France and Italy, seeking allies that would help him oust his uncle and potentially strengthen his Duchy. The Reconquest had stalled south of the Pyrenees, and the Catalan thought it would succeed with ample aid from France and Italy. Aicard was just one of the friends Ramon Berenguer had acquired along the way, with the young man providing financial aid to Aicard when Rome had turned its back on the Archbishop. Aicard nominated Ramon as Dolca's husband – whether that idea was Aicard's alone, or he was helped along by Ramon himself, is unknown - and the match seemed made in heaven to Gerberga. Barcelona was growing in power and had its own long-standing quarrels with Toulouse. If Provence and Barcelona were united, Toulouse would finally know how it felt to be threatened instead of to do the threatening. Aicard had his own reasons for promoting Ramon, as the church was also at odds with the Duke of Toulouse, and alienating him was a major priority.

Predictably, the liege of Toulouse rejected the match on insubstantial grounds. Gilbert disregarded his Duke's disapproval, and went forward with the marriage plans anyway. The disloyalty was met with a shocking reprisal. Gilbert returned to Gevaudan in the autumn of 1111, as he did frequently over the thirty years of his marriage to Gerberga. On the night of his arrival, the 57 year old was suffocated with a pillow in his bed. The assassins were unknown, but it wasn't hard to guess who sent them. Following the death, the Duke of Toulouse wrote to Dolca in Ales, relaying his sympathies and inviting his “beloved cousin” to Castle Toulouse in order to give her the Coronet of Gevaudan. Dolca did not leave the safety of Provence, the Bosonid court suspecting that death surely awaited her. Gerberga, stricken by grief over the murder of her husband, became quite ill. As her condition worsened, the marriage was approved of in January 1112, and Ramon Berenguer was sent for.

Ramon sailed from Barcelona as soon as he received word. Ramon Berenguer was no stranger to courtly intrigue, as he also barely made it onto the throne of his Duchy. His father and uncle were twins, and co-ruled the Duchy for eight years. His father was the first to wed, but the conception of Ramon was kept secret. His mother, Mahalta of Apulia, was hidden by – ironically enough – the Duke of Toulouse (the father of the current said Duke) during her pregnancy. News of the birth had not yet even reached Barcelona when Ramon Berenguer II lay dead. Though never proven, it was always popularly thought his twin brother, Berenguer Ramon, had committed the act – some even said he did it himself. When news of the birth reached the Duchy, the infant succeeded to his father's half of the co-rule, but the surviving twin became Regent. For a time, his uncle had undisputed control of Barcelona as co-Duke and Regent, but he came up against an enemy too popular to overcome - El Cid. When Barcelona's armies failed under the murderous twin, El Cid – furious, and blaming him for defeats in general in the Reconquest that year - condemned him outright as a murderer. The court of Barcelona was rocked by the public accusation of their Duke by the most acclaimed man in Spain. The court secured the way for Ramon Berenguer III to return to Barcelona in 1097, then ousted his murderous uncle, and proclaimed Ramon Berenguer the sole Duke of Barcelona.

Married once already to Maria Rodriguez, the second daughter of El Cid, Ramon's first union produced only one daughter, Ximena. Tragically, the difficult birth of Ximena made Maria Rodriguez very weak, and she never fully recovered. For eleven months, she was bed-ridden and slowly wasted away until her death. Ximena was weakened from the difficulties of coming into the world as well, and was frequently ill. Ramon remarried, desperately hoping for sons – or even just a healthy daughter – but to no avail. His second wife, Almondis, fell ill in 1109 and died childless. Ximena, never truly well, contracted consumption and died in 1111 at the age of 7. Ramon was facing a situation where the closest heir was a fourth cousin – and that was making the rather optimistic assumption that the half-dozen families the women of the Barcelona clan had married into wouldn't challenge such a succession and plunge the Duchy into war.

House de Barcelona, 1112, in serious disrepair

Ramon was practically smuggled into Provence. His departure from Barcelona was kept secret from everyone outside his immediate circle. When his boat landed in Marseilles, he disembarked in the garb of a monk and traveled to Arles under the guise of a friend of Aicard. The court of Provence was understandably cautious. The Duke of Toulouse believed that he had a strong enough claim to press his right to Provence the moment Gerberga took her last breath – Dolca, after all, was a daughter of a non-matrilineal marriage between Gerberga and Gilbert de Millau. Dolca was not a Bosonid, officially, but a Millau. The Duke of Toulouse, as the son of Gerberga's older sister, had just as much right to Provence as Dolca – if not more, being male. The Duke would intervene to prevent being outmaneuvered if he could, so the marriage had to be held in secret.

Arles, circa 1100

The day after the “monk” came to Arles, a small group of people gathered in the personal chapel of the Chateau Tarascon, the castle north of Arles from which the Dukes of Provence ruled. Ramon and Dolca saw each other for the first time – both were dressed well, although plainly for a wedding of such importance. Ramon later described his bride to his Chancellor as “timid and not terribly attractive.” Dolca wrote a letter to her cousin that her groom “had a warm and likeable personality, and a plump belly.” Neither was particularly taken with the other, and they both seemed to stress the merits of the marriage for its political prowess. The ceremony was quick and forgettable, sans for the elderly and victorious Aicard presiding – he was 72, and rapidly coming to the end of his tumultuous life. This wedding was to be his last act in his capacity as a priest.

After the ceremony, the couple were whisked upstairs where they were introduced to the court of Provence – with the Duke of Toulouse's Ambassador present - as husband and wife. The Ambassador was pleasant, but his report home was anything but. “A shameless power play to blunt your rightful claims to this Duchy” is how the Ambassador relayed it to his liege. In Toulouse, the Duke despaired. A decade of building allies to make a claim on Provence was wiped away in an instant. Though his spymaster recommended eliminating one – or both – of the couple, the Duke did not advance such a plot. He knew that no assassination or claim on Provence could take place now, as any move by him would be met by the combined force of Provence and Barcelona on his eastern and southern border. The Duke of Toulouse had to sit and stew in his failure.

The gaiety over the marriage, and the victory over Toulouse, was short-lived. Already there were troubling signs about the union, as rumors spread throughout the castle that the couple had not yet consummated their marriage. Dolca, it is said, was turned off by her husband's portly figure, and was too shy to engage her husband sexually. Ramon, for his part, was dispassionate and uncomfortable with physical relations – an impediment to both his first marriages. A fortnight after the ceremony, Duchess Gerberga summoned Dolca to her deathbed. Gerberga gave her daughter advice, trying to force the couple into a stronger bond. “I did not like Gilbert when first I married him, for ours too was a political marriage. Open your heart to him, and you will find warmth for him. In time, that will turn into devotion and possibly even love.” The Duchess passed away that evening with Dolca and Aicard at her side.

Once again, the Provencal court scurried into action to avert disaster. The next morning, while the body of Gerberga still lay in her bed, Arnau de Marseilles – the most powerful and talented man in Provence – drew up paperwork to bind Barcelona and Provence together so tightly that nothing short of absolute ruin would sever the two. Ramon was given right to rule in the name of his wife, effectively ceasing Provence's legal status as a dominion of the Holy Roman Empire. With the two Duchies now effectively one entity, Ramon summoned part of his court to Chateau Tarascon to, for now, govern from Arles. Assuming the marriage resulted in an heir – which was still quite tenuous - Barcelona and Provence would be irreversibly bound.

Barcelona and Provence, 1112, like two peas in a pod

Author's notes: Wow, no paradox game since HoI 1 has thrilled me enough to do an AAR. Kudos to everyone who worked on CK2, this is probably my favorite game of the last three years! Hope you all enjoy my AAR as much as I am enjoying playing CK2!

As for the AAR itself, I was looking for a quirky time or place to play, preferably a Duke or minor King apart from a more powerful liege. When streaming through the start dates, one year at a time, I discovered Barcelona and Provence became united in 1112. Never knowing anything of this history, I looked it up and found this union of the two rather neat. So, here we are. No modification to the game made. Start day is 02/03/1112 (the factual date of the wedding of Dolca and Ramon Berenguer III), end date will be when my lineage dies out. Whilst the two are united, I shall call my country Barcelona-Provence, and my dynasty Barcelona-Bosonid, even though it just says Barcelona there on the map and Dolca is technically a Millau due to marriage madness.