Under the Southern Cross - a semi-interactive Imperial Brazil AAR

- Thread starter Lyonessian

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Voting's up.

Caravelas: 6

Lima e Silva: 2

Vergueiro: 2

In a somewhat surprising, overwhelming early vote, it's bound to be the Marquis de Caravelas who gets his vision forwards! As the author, I must say this is creating an already interesting scenario. I see it producing early differences. I'm happy with garnering 10 votes this early on, too! The next update is nearly done, it will probably be split in two since the first part will require an intro to some new characters coming up. First part in tomorrow, the second a few days later.

As an overview, your overall positions and justifications have made historical sense. Michaelangelo said of keeping a safe conservative course, Cloud Strife saw in Lima e Silva a representative of the military concept of Order, as GangsterSynod saw Vergueiro as Exalted opposition to the former status quo. One pointer: how their provincial background and political positions mingle will make a big difference. The decentralisation dilemma comes knocking!

Caravelas: 6

Lima e Silva: 2

Vergueiro: 2

In a somewhat surprising, overwhelming early vote, it's bound to be the Marquis de Caravelas who gets his vision forwards! As the author, I must say this is creating an already interesting scenario. I see it producing early differences. I'm happy with garnering 10 votes this early on, too! The next update is nearly done, it will probably be split in two since the first part will require an intro to some new characters coming up. First part in tomorrow, the second a few days later.

As an overview, your overall positions and justifications have made historical sense. Michaelangelo said of keeping a safe conservative course, Cloud Strife saw in Lima e Silva a representative of the military concept of Order, as GangsterSynod saw Vergueiro as Exalted opposition to the former status quo. One pointer: how their provincial background and political positions mingle will make a big difference. The decentralisation dilemma comes knocking!

CHAPTER TWO, PART ONE

THE NEW ORDER

THE NEW ORDER

Shortly after the departure of Pedro I to Europe, which was met by a turbulent reaction of popular effusiveness coupled with the need of the political elite to act quickly in order to maintain control over the nation, the issue of Regency began to show its full spectrum of colours. Vetted and promulgated by a young Pedro I, still unaware of the kind of troubles he would go through during his time sitting on the Brazilian throne, the constitutional mechanisms regarding Regency had been almost like a second thought. The Emperor had been the centrepiece of the declaration of independence. His lack of experience in reigning had been overlapped, in the minds of those who analysed the political situation of 1822-1824, by his deep ties to the land of Brazil, where he had been raised since the tender years of infancy. Pedro was 25 years old at the time of the bestowal of the constitution, overconfident in a long and stable reign, besides having the unquestioning support of José Bonifácio, regarded as the most brilliant Brazilian mind of his generation. How would the terms of regency feat so importantly in his legacy? Why should it be the hill on which monarchical, republican, popular or elitist cadres should die on? Any observer would think such thoughts mad, or disconnected from the present conjuncutre of power.

Nevertheless, the same Regency which was largely ignored in 1824 came to the fore less than a decade later; its terms, put together in a late-night discussion in the Privy Council, were now to determine who held the helm of State. The head of the ever-threatening Moderating Power - the bane of liberal thinkers from Rio Grande do Sul to Pará - was a five year old boy, whose physical head had not yet been fitted for any crown, and whose acclamation required a helper with a chair, lifting him up on the balcony, so that the people could see their Emperor. The Provisional Regency gathered; their heated discussions to carry a weight no man in the room had wanted, or predicted, until but a few weeks before that day.

The acclamation of Emperor Dom Pedro II, April 1831

Upon further analysis of the motivations and intentions of the three men gathered in that room, there appear to float, today, a significant number of scholarly interpretations, diverging chiefly on their hermeneutics. The first hypothesis looks at the episode as that of an "Old World" style, involving self-interested and only partially rational members of the notáveis, in combat over personal prestige to themselves or their client network of political affiliates. The second hypothesis sees in the 12th of June, 1831, the elements of an uniquely Brazilian political dispute, of which the primary division would be that over the centralising and decentralising forces. "Who holds the largest power: the Court or the provinces?" seems, to these analysts, to be the unresolved question the Regency inherited from 1822 and 1824.

On one aspect, both hypotheses agree: almost none of the voices with an ability to be heard at the time could conceive of a Republican Brazil. The major contributing factor for this position is not, as present-day analysts may think, that somehow the disparate interests and political activity of the notáveis were driven by an ideologically reactionary or conservative bias. It has, instead, been largely evidenced that it is a result of pragmatism in essence. One common fear the landowning and bourgeois classes had always presented along the independence process was the fear of "Hispanicization". That is, that Brazil should suffer, in her pursuance of autonomy, the same fate of Spanish America, fragmented into authoritarian, caudillo-led republics in which the Brazilian political elite could see neither the features of classical republicanism nor that of contemporary - mostly American - republicanism. Such rupture in the political and historical fabric of the nation would not only lead to possibilities of growing irrelevance on the global stage, but also the fears, in heavily slave-populated provinces such as Rio or Bahia, that there should be a resurgence of Haitianism - with ominous hints to their own survival. The only way out of this dilemma would be that of the preservation of the monarchical institution: the Emperor - and him alone, according to some - was the binding force of the Empire, assuaging most concerns. Thus the long wait for the reign of Pedro II had begun; its destination, and the men who would drive the nation there, yet unknown.

The Marquis of Caravelas, c. 1828

This complex network of interests crashed over a full day inside the Imperial Palace: its winner an unlikely one. The Marquis de Caravelas had been an habitué of the Imperial Court ever since its transfer to Rio in 1808, his position strengthened not only on the backs of a healthy personal income, derived from his Bahian estates, but also on the clever managing of his status and building of connections inside the palace. After independence, his position would be held together in the firmest way possible: by way of appointment to the Senate, followed by a seat, and, in time, the leadership of the Privy Council. Caravelas' name was featured in the Constitution of 1824; he had observed from a window as the artillery was brought into the Acclamation Grounds overnight, spelling the doom of Liberal and Exalted constitutional proposals. He was a clear believer in the principle of a strategic building of alliances, even those which would contradict perceived ideology and roles of its integral parts, as the foundation of a government which could act decisively and carry weight behind its decrees; even, if need be, antagonizing interests perceived as polarizing. He was, by no means, alone in such enterprise: inside that room, Caravelas "spoke with a voice of 5 million pounds" as some critics would later pen it - meaning his action was merely the materialising of the wills of the landowning class. It was his adherence to such a course of action that strengthened the projection of his will: he watched intently as the polarizing force of Exalted Vergueiro stood obstinate against the military verve of Lima e Silva, proposing common commitments, and, even though rejected time and again, still maintaining his position as the most desirable ally to both his fellows. The discussion had been won by wearing down all options which could imprint a defined "national project" upon the First Regency; the men of most repute, and with the most perceived capacity to keep stability, had been selected. Granted a choice to be among them, Caravelas made it a point to honourably withdraw himself: "I am an old man; let those with panache lead, for my wish is to live quietly".

Within two days, the crowd attended to the public announcement of the First Regency, which had been chosen criteriously, following most of conditions under the constitutional mandate of Caravelas. Most, however, wasn't enough: it had been suspected that Caravelas would keep his nominations within the ideal requirements that the hierarchy of the General Assembly disposed in 1824. But in a sweeping move, in fact, one which the Aurora Fluminense (a respectable clarion of Liberal persuasions at the Court) would call "the conciliatory maneuver enshrined", Caravelas had proposed to break the deadlock over the First Regency with the option of a leading appointment from among the Senate's halls, with the second half of the regential diarchy being composed of an influential Deputy. In this maneuver, Caravelas envisioned the prospect of an Assembly working in tandem, as if owing the Executive a conciliatory approach in exchange for equal representation within that power. If there should be enemies and threats to the State, then they should come from the outside; a harmonic political machine would weather the torments. Such a proposal would have had a slim chance of acceptance between the Provisional Regency, unless they could find in the Deputies an outstanding voice, someone which could appease the popular sentiment in order to disguise the institutional innovation which made it possible. Fortunately, Caravelas had just the man for the job.

The Marquis de Barbacena, c. 1831

First among the regents was the imposing figure of General Felisberto Caldeira Brant, the Marquis de BARBACENA. At the age of 59, few men in Brazil could boast the long résumé of Barbacena, and none other than Bonifácio himself could command the respect of notables towards the First Regency. Descending from the diamond-mining aristocracy of Minas Gerais, Barbacena had rejected a comfortable yet tedious future as the administrator of the family's estate, moving to Rio at age 14 in order to take the required exams for cadet school. It was to be so, with a letter of recommendation from the Viceroy of Brazil to pursue studies in the modern, recently founded Lisbon Marine Academy, where he could achieve the patent of Lieutenant-Colonel at the age of 22, serving forces in land and sea to missions in England, Portuguese Angola and being the first Brazilian-born officer of a mainland regiment. His political activity blended with his military action; serving as an honest broker for the peace at Pernambuco in 1817 and mediating between Bonifácio, Britain and the Portuguese Cortes in 1822. After serving as Chief Commander of the Imperial forces in the Cisplatine War, he was appointed to the Senate and many offices in the Ministry, where experience and seniority would make him, under the right conditions, a near-universal choice for the First Regency. Barbacena was of a quiet public profile, serving in many occasions as an éminence grise, and his allegiance to the Bonifácio vision of Brazil lent him credence and respect from among the halls of notables. However, his subdued personality, lack of identification with a political faction, and individual history appealed in no way to the middle classes with influence, perhaps mindful of an extreme aristocratic force spelling the barring of liberal policies and a more active insertion of Brazil into the transforming global networks of trade and influence.

Bernardo Pereira de Vasconcelos, c. 1837

The second half of the diarchy was filled by Bernardo Pereira de VASCONCELOS, a 36-year old rising star handpicked from the lines of the Conservatives. Vasconcelos had, until then, been hailed as the "model man" of an independent Brazil owing to his trajectory: born in Vila Rica (Minas Gerais), within the mineiro plutocracy and Portuguese pedigree alike, he took advantage of the privileges of a Coimbra Law degree to return to Brazil in 1820 and inflate the ranks of the magistrature - in theory. In practice, Vasconcelos had denied positions and taken various leaves of service until he saw the clearer path to power in the new Chamber of Deputies. Using his familial connections, he was elected to the first legislature of independent Brazil in 1825: his first action while in the Court, the founding of the O Universal newspaper which published screeds of protection to the regional autonomy of Minas Gerais as frequently as it spread discontent towards "Petrian absolutism" after the defeat of Brazilian forces in the Cisplatine War - until the abdication of 1831. It had been him, working in a crossbench initiative besides Vergueiro, who forced the Ministry of State to deliver accounts to the Legislature in 1826; in 1830, his vitality in the Chamber was crowned by a controversial speech in which he declared, en passant, his period in Coimbra as "uneducation, the opposite of what it should have been; Portugal attempted to produce in me a barbarian, yet I free myself of those chains". Outside of his legislative activity, Vasconcelos was regarded as keen and clever; he saw in the British monarchy the clear model to be replicated in Brazil, for national unity in the Empire could only be forged by an "eternal institution", free of partisan projects or a priori policymaking. Vasconcelos had captivated those who agreed with his speeches, and burned bridges with any pro-Portuguese sentiment or those approving of Pedro's measures. Those who perceived in Vasconcelos the outburst of progressive rage, his public persona, failed (where Caravelas succeeded) to understand his deep-lying conservatism and desire for the system to remain as it had always been; no matter what its elements may shout at the Heavens.

June 15th, 1831 edition of the Aurora Fluminense (or simply Aurora); its motto to maintain the Constitution and sustain Independence, once turned against the "despotic desires" of D. Pedro I, now turned against the Conservative-led First Regency

The First Regency would set, then, the stage of a new era of Brazilian politics. The long-term visions of what should be Brazil, and the drive to implement the reforms necessary - whatever flavour might they possess - had been pushed aside, in favour of an Executive which could run an orderly ship, innovate carefully and ingratiate the Legislative in most of its nuances to tag along. It had been, par excellence, a triumph of Burkean conservatism, if only on paper. The question of whether such a system could be threatened became a doubt whispered in the Chamber's recesses; what change can really be promoted, when Order patrols the Court? A distinct change in the patterns of discourse of the contemporary press can be noted: the inability for outsiders to influence the early decisions of the First Regency raised concerns. The Aurora stamped on the bottom of its first page a vigorous and loud Vasconcelos, small, Napoleon-like in his features, contrasted with the Prussian Barbacena in the ivory tower of the Senate. The Emperor, shut with Bonifácio in São Cristóvão, both with strict agency, partially isolated from the political landscape.

The elections of September 1831 only marginally reproduced the silent rumble of the people. The 1824 adoption of census voting, and the strict requirements over income which disenfranchised many among the liberal middle classes from electoral colleges with a direct say on deputies and senators, curbed the possibility of a reaction to the "business as usual" affairs in Rio. In fairness, it must be said the restrictions 1824 put on political participation were not unusual for its time, and possibly reflect the same anxieties as those enforced in Europe after the establishment of the Congress system; a valid comparison would be that of contemporary France during the second half of the Bourbon Restoration. Overall, estimates put at around 150,000 the number of people with suffrage at any electoral level, corresponding to roughly 8% of the free male population, and 5,8% of total male population. It was a system built to guarantee what the notáveis described as "good representation", in which the adjective takes on the connotation that only upstanding members of, or with connections with, "polite society" could find an outlet for their political views. The returning legislature was not much different from the past one, comprised of roughly the prior representations of Exalted, Moderate and Conservative legislators, though the overriding factor which made many of such allegiances fickle was that of the regionalist question. As the Correio do Rio, which found itself driven further and further into the Exalted camp, wrote: "The question of the National Sovereignty cannot be answered by the initiative of Chambers upon which shines no Popular Sovereignty [...] To address Reform is to deny the Streets their forceful anger".

44 Conservatives, 26 Moderates and 32 Exalted-Liberal Deputies comprised the 4th Legislature; little electoral swings, the marginalization of the "Portuguese faction" and silenced protests against the iron grip of the Right

In the Court, the largely stagnant Senate and Executive carried on their daily tasks and prepared for the brunt of the work to come in working with the new legislature, extraordinarily called to sessions at the start of November: the matter of discussion, the establishment of new institutions which could protect provincial stability. Before most of the new faces coming in from the provinces could be seen in the halls, the news outsped their carriages.

The president of Bahia reported a garrison revolt after a decree limiting officer patents to Brazilian-born men in the Provincial Militia... the killing of a Brazilian major by a Portuguese captain erupted into a neighborhood chaos... the president of Pernambuco notices popular unrest among tradesmen, seamstresses and other poor mixed/white groups... there has been notice of independent bands breaking into the Recife Naval Armory, their allegiance as of yet undetermined... both raise the alarm and request for central government's support...

****

To come on the second part: law and order, social movement and change, foreign affairs, the economy and the arts. ETA at close to next weekend. Feel free to comment and conjecture

Last edited:

- 1

Tentative moves towards a new future. It feels like there’s still plenty of tension left unresolved between all the various factions. Where will the deadlock break, I wonder?

I'm curious, though a bit worried about how Caravelas will use his influence.

I like the Barbacena Vasconcelos diarchy though I feel that Vasconcelos will wear the pants in the relationship.

I like the Barbacena Vasconcelos diarchy though I feel that Vasconcelos will wear the pants in the relationship.

Yes, I have a feeling that the (non-Portuguese) Conservatives of this time would steer the course even with a huge storm around them.Tentative moves towards a new future. It feels like there’s still plenty of tension left unresolved between all the various factions. Where will the deadlock break, I wonder?

He was a smart cookie to get out of the way in this situation. If there is fallout, his name stays pristine. And yes I'd say Vasconcelos is perhaps the most self-driven personality in the Court... they tend to get anxious with these obstructing elder statesman figures. All remains to be seen!I'm curious, though a bit worried about how Caravelas will use his influence.

I like the Barbacena Vasconcelos diarchy though I feel that Vasconcelos will wear the pants in the relationship.

Thank you kindly! Feel free to drop by and follow us anytime.I must say, it's always a joy to find a AAR of such quality on the V2 forum!

I'm using the game loosely to get references on numbers, trade and military units. Other than that, the events usually lead to too ahistorical outcomes, so I'm modeling those based on knowledge about the period.Just curious: are you using mods or playing vanilla?

As a heads-up: I have been caught up on work for now, so the ETA for the next update should extend a little to the middle of next week. It will bring together with it one, maybe two questions, and take us at the very least into 1835!

CHAPTER TWO, PART TWO

HOPES AND FEARS

HOPES AND FEARS

The year of 1831 seemed endless to those who withstood it: it started with tension, and ended with fire.

In early November, when the Court received news of diverse hotspots of conflict in the Northeast, the Regency was quick to act. In fact, this response had surprised many: liberal dispositions at Court had been long advocating for a reduction of the military effective force, either by means of disbandment or redeployment. The strength of such ideological screeds dominated the intellectual and political spaces of Rio, conducted carefully by the editorials of the Aurora. When the conservative First Regency took hold of the Executive, many observers expected that their firm hold on the Assembly would depend on careful negotiation with those of Moderate and Exalted factions - the question of the Army was supposed, and expected, to be one of the first concessions Barbacena and Vasconcelos would provide to the Legislative Left. After all, the threat of tyrannical absolutism had been gone with Pedro I to Europe: why maintain such power stocked in the strength of the armed forces?

What the Moderates and Exalted deputies wanted, then, found itself rejected by the necessity of the State. Even before the sessions began, the First Regency saw the need to exert control over the unruly, decentralized Empire. The garrisons located in Bahia and Sergipe received their call - their mission, to overrun whatever sniff of unrest they could find in Salvador. The early repression in Bahia presented a difficult quandary to government, both local and imperial: when does strength turn to despotism? When does resolve turn into paranoia?

The historical reports are still unclear, but most interpretations agree that the occupation and policing of Salvador by Brazilian troops, which lasted over a month in December 1831-January 1832, had been a disproportionate response. The issue ran deeper; it showed the problems of loose organization when one is dealing with the force of arms. The Bahian provincial militia could have dealt with the situation, most seem to consider today. However, the sparse resources and the political use of the militia by the local government had turned it either difficult to control and command, or thoroughly useless. A small riot had led the President to overreact; the Imperial forces left the populace in a constant tension over issues that many contemporaries saw as nothing more than a "garrison brawl". Salvador had been controlled without any shedding of blood, but with an egregious number of arrests. Were all these men rebels against the Regency, or the idea of Brazil? Or were they simply, concretely, those wretches on the margins of society, who saw in revolt a chance to grab a few riches, or make a local name for themselves, to rise above their station in life? The poor had been, naturally, overrepresented in the criminal records by the time the Imperial troops left the city to rule itself; in their trail, a bitter taste of injustice.

Rendezvous at the Carmo Church; the cerimonial guard meets Church authorities on the outskirts of Salvador, before the pacification of the city

The situation in Recife, however, turned out to be considerably different. The Court had not been fully aware of the social movement which arose in the public squares of that city 2,300km away during the winter of 1831, but it would fall to the consequences of it nonetheless. In the Brazilian Northeast, the paucity of transportation and the geophysical limitations imposed by the landscape made the provinces therein be populated by different quasi-micro-societies; each town and parish their self-contained universe, with one or two representatives of the so-called "traditional families" serving as the links to the outside world, establishing with it connections of conflict or patronage, modernity or reaction to it. The largest part of society, that grey social grouping most commonly called today as the Popular classes (or populares, in lexical opposition to both seigneurial and slave classes), impossible to define by race or occupation, populated by Whites (poor or of modest income, many recently-immigrated), Brazilian-born Black freedmen, and the Pardos (persons of mixed Black-Native-White ancestry), were left to their own devices, on little or no support or oversight by local authorities, and no formal ties to the economic foundation of the Empire: that of slave labour and plantation management. Their insertion in society came, mostly, through middling irregular trade and taking up simple offices ancillary to rural or urban activity, such as husbandry, tailoring, rope-making and the like. In larger centres, such as Recife or Olinda, the populares could aspire to a greater status; perhaps the most common higher ground would be a posting in the administrative bureaus as low-level bureaucrats.

When the balance of power at the Court was tipped from the uncertainty after Pedro I's abdication into the new Conservative-led First Regency, the dominoes set up in the Northeast promptly fell. It would start in the small towns of the Pernambuco countryside: in Garanhuns, an old settlement of Portuguese resistance against Dutch invasions, the local elites rose up in protest against increased centralisation and the imposition of taxes by the local government. Such taxes had been raised as a way to increase provincial revenues and sustain the required contribution by the Court, which had been seen as abusive under Pedro I and for which the prospects of the First Regency weren't seen as much better. Soon the news spread: landowners across the Pernambuco midlands were settling their disputes by means of force and threats to Recife. In Recife itself, the concerns affected the populares instead. The flat taxation system adopted by the Court to urban professionals - outside of the land tax over 1/6 of the annual income - was also a direct means to curb their spending power and block any chances of either survival or social climbing. The Recife revolt began in earnest in early November: groups of populares set up the barricades around the central district, isolating half of the island which made up most of the city's extent. They had broken into the Naval Armory, supplying cabinetmakers and seamstresses alike with guns and ammunition. The provincial militia had been called, garrisoned across the bridges; their limitations and poor organization, about the same as that of the Bahian militia. Soon four regiments of the Brazilian Army had been directed into the city limits, with one cavalry regiment being sent to the midlands in order to quell the loosely organized landowning concerns. The leader of the Imperial forces had been directly appointed by Barbacena: the Marquis de LAJES stood ahead of the column ready to take Recife from the rebels.

Lajes had been a veteran of the Peninsular War in Portugal, and became very adept to unorthodox tactics throughout his carreer: these skills would come as boons for the Imperial Army in Recife. By January 12th, the connections of the central island of Old Recife to supplies coming in from the countryside were severed; the skirmishes happened along the bridges. The rebels directed naval cannons to the buildings of mainland Recife; cannonades and rubble threatened the Imperial positions. Soon Lajes would find his men fighting on two fronts, as insurrection broke out on the mainland and a ragtag company of populares came into the capital from neighbouring Olinda, setting their own barricades, using women and children as agents of supply. Amidst the fighting, not all combatants were fully aware that they fought for an ideal commonly called "petit-bourgeois", and the most radical claims of the leadership in both Recife and the country towns were those of local autonomy to Pernambuco under the Empire. Soon two agendas developed: the landowners and bureaucrat populares held urgency committees in torn down halls, speaking for their rights as Brazilians, while the rest of the insurrectionists, populares of Recife and Olinda, shouted "independence" atop the barricade. The Imperial Army advanced and retreated along the coastline; occupying and surrendering bridges, retaking government positions, blockading supply boats into Old Recife.

The Marquis de Lajes; representations of the Siege of Old Recife became a favourite painting motif years after its distressing details vanished from public mind

The Siege of Old Recife lasted for over 4 months. The increased disorganization amidst rebel leadership opened up their lines; Lajes took his chance on May 23rd, and drove a full regiment over into the Old Town. What they found was a scene of desperation; the populares, prevented from receiving resupplies of food and other goods, surrended with emaciated bodies and tired minds. Children begged the soldiers for bread; most of the elderly had succumbed, either cremated or buried on common graves. Widows had been produced every day; this pushed them into a war of their own, attacking the Imperial forces with stones, throwing sticks. Once Imperial control was regained over the Naval Armory, Lajes produced a missive to the Court: "We have prevailed, by the grace of God and in protection of the Empire; yet no matter how full our victory, I feel our defeat is just as thorough".

The Recife Rising of 1831-32 had drastic consequences for Pernambuco and her relationship to the Court. The divisiveness of the landowning class - between countryside uprising and urban appeasement of Lajes - had made the political climate especially tense when order was restored. The necessity of such a siege, and the destruction it could cause in a vibrant, booming port city also spelled hardships for provincial and national economies. Trade was reduced in the Port of Recife by almost 20% by the final months of 1832, with most trading routes to Europe, Africa and the West Indies finding cost-effective ways to relocate to the Port of Fortaleza (in the province of Ceará) or that of Salvador da Bahia. This brewed further instability in Pernambuco; landowners were especially sensitive to the increase in freight prices in order to move their goods to other provinces. This brought an up in costs and raised an already abusive barrier-of-entry into the plantation business; not to say, it increased the local demand for slave trade from Africa in order to increase productivity. The issue of slavery, which had been a tarnish on Brazil and its position in the world, was poised to turn into a larger issue.

.jpg)

Abolitionism had become an important worldwide movement; even in deep slave societies as that of Brazil, the issue, which seemed to be far from the political hotspot, came to the fore with immediate consequences during the early 1830's

On the years following the Slave Trade Act of 1807, Britain had gradually increased her power projection on the global ocean. A natural consequence of such a naval expansion, developed to follow the growing demands of empire, was that the Atlantic became embroiled in a game of cat-and-mouse on a planetary scale: while the Southern United States, Brazil, and even the very same British Antilles continued to depend on slave labour, British ships had been given increasing leeway in pursuing and seizing slave ships out of Africa. On the interest of maintaining profitable mutual relations, the issue was not raised in earnest or with any regularity or intensity by British ambassadors in the Brazilian Court; the Brazilian elite, itself largely benefitting from such neglect, stayed their course. However, as abolitionism grew into a distinct and powerful social movement in Britain, the United States and even in the most progressive urban centres of Brazil, the British position was also bound for a change. Upon assessing the results of the early restoration of stability that the First Regency had achieved in Bahia and Pernambuco, the British plenipotentiary minister Lord Ponsonby requested a meeting with Barbacena and Vasconcelos: on the table was the delicate matter of the slave trade. The sources available to us at the present moment allow for a glimpse of both Brazilian and British interests over the question. Lord Ponsonby denounced not the maintenance of illegal slave trading as a general rule to Brazil, but simply called attention to the fact the increased slaving activity in Recife during the rest of 1832; a fair induction over this discourse's content shows that Britain would be willing to turn a limited blind eye to Brazilian slave traders, and not an expansion of that dreadful commerce. The meeting having ended on polite, temporizing solutions, the matter of foreign policy began to unravel over the First Regency.

After the Cisplatine War of 1826-27, with the Empire suffering a defeat to the liberal republican forces of the Banda Oriental of the River Plate (now Uruguay), the economic and trading prospects of Brazil turned foreign policy into a contested, drawn-out struggle in the Southern Cone. The Brazilian population centres had been notoriously coastal - around 90% of the population in 1831 lived on settlements up to 200km from the Atlantic shores - and the challenge of "interiorisation" was until now a Promethean one, while transportation and communication technology available could not break through the hilly savannahs and tropical forests of the deep backcountry. On the southern reaches of the Empire, in the provinces of São Paulo, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul (particularly the latter two), the opening of new roads and trails, with accompanying trading routes into the backcountry had already begun in earnest since independence. The Court had a particular interest in these areas, seeing them as ways to protect the trading waterways of the Paraná-Plate River Basin, and settle even more Brazilians or Portuguese along the border as a means to secure Imperial interests and territorial integrity. With the loss of Cisplatina in 1827, direct access to the Plate Estuary was cut; this meant that the main river routes of the basin turned into a major strategic asset to the Empire. Naturally, this would lead to tension and protracted conflict over trade and moorings on both sides of the Paraná river, and the local landowners and merchants feared that any foreign policy instability coming from Rio would lead to a joint Argentinian-Uruguayan blockade of the estuary to Brazilian ships - and their subsequent increased costs of freight to lead produce towards the Atlantic port cities of Santos, Desterro or Porto Alegre. A particular characteristic which made the southern landowners even more vulnerable to such distress was the fact that slavery was not prevalent in the 2 southernmost provinces as it was in the Court or Minas Gerais - for instance, slaves were approximately 7% of the Santa Catarina population in 1835, compared to 35% in the Court and 21% in Minas Gerais. A recourse to increased slave trading, already disencouraged by other factors and now effectively prohibitive after Lord Ponsonby's warning made the situation extremely delicate.

The Platine Basin with highlighted major waterways in 1835; the loss of Cisplatina had wrestled Brazil out of direct control over the Plate Estuary to the south, which preesented unique difficulties for transportation of produce originating inland

While this was on course in the south, in the Court the First Regency carefully weighed over the positioning of Brazil on the global stage. On most issues, the two regents could strike a careful balance: Barbacena representing the old aristocracy tied to military and government service, Vasconcelos being a young and passionate figure, amenable to the petite-bourgeoisie and the tepid liberalism of the middle classes. Foreign policy, however, proved to be the decisive wedge between the regents. Barbacena had been personally affected by the defeat of 1827, when he had top command of the Imperial forces; he had not forgotten the humiliation of Brazil at Ituzaingó, where the United Provinces had driven a sizeable part of his men into arrest or missing in action status. Therefore, he led a faction of the Conservatives which was driven widely by a quasi-revanchism, and founded their opinions of the Argentine Confederation upon the groundwork of enmity and mistrust. Barbacena could not yet conceive of the Empire as being bottlenecked by "Spaniard ranchers" on the geopolitical stage; the Banda Oriental had been Portuguese, ergo, it legitimately belonged to Brazil. Therefore, when the Argentinian ambassador joined Lord Ponsonby in formal protest over the increasing slave trade in obedience of the bilateral Argentinian-British Navigation Treaty of 1825, Barbacena and Vasconcelos came to blows within the Imperial Palace. The marquis sought a reprieve against such threats to sovereignty; Vasconcelos, being of a cooler mind, wanted to temporize and seek to asssuage British and Argentinian concerns by means of domestic policy which could curb excesses in Pernambuco. His proposal was to seize the day: the regential disagreement over this matter spilled over into the General Assembly, where the Senate's mild approval of Barbacena's proud retort could not counter the fiery speeches being shouted at the deputies by Moderates and Exalted alike. The Aurora followed discussions closely, over weeks; the records agree in that no real opposition to the slave trade could yet be found in these halls of notáveis, yet they mostly recognized the importance of a careful hand in placating British pressure. The Chamber won the struggle, and a package of tax reform regarding the provincial contributions to the Court was agreed upon in June 1832. The news coincided with a slow recovery of the economy in Pernambuco, with a "tense peace" allowing once again the major Atlantic trading houses to deal directly with Pernambuco authorities without fears for unlawful seizure of goods or openly corrupt practices. While this response, led by the Vasconcelos faction, was good enough for the short-term, it wouldn't do much else than delay the unavoidable conflict with Britain over the slave trade - and whether it could lead to another conflict with Argentina.

As Pernambuco and the southern provinces experienced economic troubles, in the centre of the Empire opportunities seemed to flourish. The Minas Gerais-Rio axis, already well recognized as the major vessel of economic activity in the nation, was benefitted by the Conservative majority in the Assembly and the Conservative leadership of the First Regency - it must be reminded that the diarchy was composed of two Minas natives. A reformed tax system, after the Pernambuco Affair, curbed most previous abuses (as the provincial governments perceived them) and allowed for the richest and most prosperous provinces to gain substantial autonomy, which also meant less and less burdens on the owners of means of production which made up the composition of such governments. In an era of limited investment in public works, the First Regency could steer both houses of the General Assembly to a consensus over the nature and function of such works. It is now recognized that the tenets of a Brazilian conservatism were first settled during the period 1831-1835, in which government policy was defined by two major vectors. These principles had been deliberated and published following a convention at the São Bento Monastery, at the Court, in April 23rd, 1833; considered the occasion of the founding of the Conservative Party, the first formal political party in Brazilian history.

The São Bento Monastery depicted on royal festivities in 1817; the imposing building on top of Morro do Castelo was the birthplace of the Brazilian Conservative Party

First, the matter of centralisation. After the experiences in Bahia and, mostly, the Siege of Old Recife, the pro-regency notáveis used the Chambers and the press alike to broadcast what they saw as a major need: the establishment of authority in a strong Court, with personnel, resources and institutions in the provincial capitals that would be the plenipotentiary representation of the Empire, with the ability to act quickly in face of any unrest or unlawful conduct which might occur locally - this was doubtlessly influenced by the experience of Bahia, in which a needlessly harsh response by blindsided Court authorities raised tensions which would not exist otherwise. Conservative publications such as Rio's Astréa (which had shifted from its liberal position during Pedro I, onto the ministerial side) proclaimed that "National Unity is, and must be, the result of a programme which is nationally planned, and headed by representation of all of the Empire's corners [...] No body politic can live without a soul".

Second, conservatism began to rally around an ideal of agrarian utopia, which they could rhetorically support, since during the First Regency the inner expanses of Brazil continued to be settled; in São Paulo, Pernambuco and the central province of Goyaz, new trade routes were opened, with every kilometer of a new dirt road connecting the backlands to the national stage, and every pier in one of the many navigable rivers being able to expand smallholds and plantations alike. The traditional Brazilian countryside settlement usually began with an "arraial", which designates a public commons around which a Catholic church was established, a hamlet grew and the cultivated areas spread on a variable radius. According to Church records, carefully kept by the religious State apparatus, the number of new parishes on the Brazilian Highlands grew by at least 247 during the First Regency - with 58 of them consolidating into new municipalities; as seminarians from the urban centres flocked to the arraiais, they brought not only religion but also the knowledge and connections with outside society at large, providing newly-settled, isolated places with at least a semblance of "cosmopolitanism". Another character of Brazilian social life since the colonial times, the "tropeiro", also came back to the fore as an agent of expansion and colonization. "Tropeiros", or "troop men/troop conductors" were an unique and diverse social strata of ranchers, cattle drivers, merchants and caravaneers, whose occupation involved grouping up with a troop of horses and cargo to trek the Brazilian countryside, in voyages which could last for years. The arraial was symbiotic with the tropeiro; one could not live without the other. As inland settlements grew and more of the territory turned into cultivated land, tropeiros and arraial authorities built their own power; limited, local, modest, yet imbued with the deep mystique of the backlands.

Tropeiro and tropeiros at an arraial market fair; the twin pillars of Brazilian settlement in her vast interior

The new political leadership grew out of the largest landowners (usually defined by land ownership but also by the number of slaves acquired) and of the "trades of science" such as the aforementioned priests, parish doctors and the like. The new landscape of Brazil was that of an ever-expanding one, physically and socially, gathering with it a multitude of new interest groups, only very loosely tied together by the necessity of means to survive and thrive in these regions far from the coast. Conservative rhetoric in benefit of the "pioneers", then, also served a recruitment purpose; the provincial assemblies elected in 1834 returned inflated numbers of notáveis who were associated with national Conservative politics, either in sincere support or as a means to secure a valuable patronage in more hallowed halls.

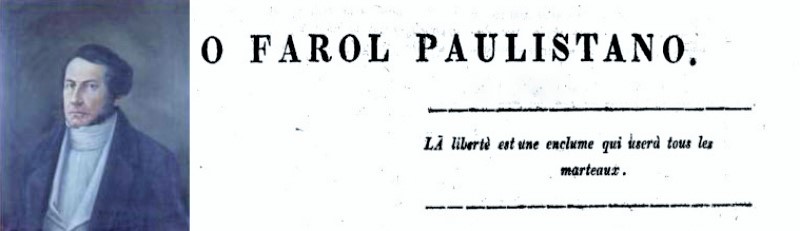

Every action carries with it a proportional reaction: in response to such a formative enterprise by the Conservatives, the issue of a distinct Brazilian liberalism had been also put on the balance. Since early 1832, amidst the turbulence in Recife, the liberal press took upon itself the task of rallying an opposition to contend with the Conservative narratives rising. Besides the seniority and political ability of Vergueiro, which had been bolstered by his participation in the Provisional Regency, there were not many leading figures acceptable to all brands of liberalism at the Court. The press, therefore, created one - the editor of the Farol Paulistano, the major newspaper of São Paulo, José da Costa Carvalho, the Marquis de MONTE ALEGRE. Monte Alegre had been involved in law and politics since the days of the United Kingdom, and secured a seat in the Deputies during the First Legislature in 1823. However, his most recognizable activity came through the founding of Farol Paulistano, in which he denounced the "perfidy of absolutism" during the reign of Pedro I. When the regency came, his voice was one of the most active in the Assembly - he refused to let the iron grip of the Right rule without constant hecklering. The particular concerns of Monte Alegre gathered around the possibility of a Petrian Restoration and the need to solidify a liberal group strong enough to deter any such adventuring. Such a movement grew around him. São Paulo had now become the centre of Brazilian liberalism, which Monte Alegre portraying this trend as if fulfilling a Providential commission: while the Court attempted to tighten its grip on the provinces, they would find not a soft little animal, but an iron knife, ready to make Brazil bleed if so needed. Vergueiro and the Exalted factions had a newfound energy; the Andrada family (responsible for the too-liberal constitutional proposal of 1823) came back into prominence.

The Marquis de Monte Alegre; the paper Farol Paulistano rose as one of the most combative instruments of Liberal opposition to the First Regency, and gave its editor a leadership role in the formation of a broad Liberal alliance

What differed from a few years ago is that now Brazilian liberals had a distinct programme, in part reactive to the Conservative buildup. This programme's caprock consisted of an unabashed defence of decentralization, with the proposal of constitutional reform in order to grant tax rights to provincial assemblies, and the refusal of any appointments to provincial executive bodies; provincial elections would exert their full democratic duties. Liberals were also concerned about the perceived blunders in Bahia and Pernambuco, yet they were not partisans of potential separatist threats either. Therefore a compromise was struck in that a Liberal government would prioritize the modernization of transportation and further regional economic integration in the South and Northeast as a ways to make the provincial economy and trade enter into a cycle of interdependency; this scheme, they believed, would bolster the security of the provinces far from the Court in a much more coherent way than by means of an Imperial military threat always looming over the possibility of rebellion. The extent of the Empire, and its sparsely populated reaches, were nothing less than the challenge to be defeated by the Court - they would need unique strategy for it. Within the liberal movement, a mild, timid third tenet arose: that of the prospects of utilizing public funds and protectionist measures to encourage industrialization. This plan, borne out of the more adaptive liberal minds in São Paulo and Pernambuco itself, was but a whisper in the inevitably landowning-dominated interest network of Brazilian politics, yet it must be recognized as the first realisation that Brazilian insertion into the world economy would gradually become threatened, if her financial futures relied only on agricultural exports. These Exalted minds, among them most notably the young pernambucan scion Antônio de Holanda CAVALCANTI, had been deeply educated on the economic sciences by means of pragmatism; they received reports from around the globe, had forsaken French and Latin for English in order to read the Times and were deeply aware of the large-scale expansion of productivity the East India Company had achieved in Asia; Brazilian development and financial stability - not to say the maintenance of Union itself - could not rely for much longer on production of the same tropical crops without the encouragement of at least the simplest manufactories, according to them.

The prescience of Monte Alegre could not have been more correct: throughout the year of 1833, rumours started to spread in the Court that the situation in Portugal had been considerably changed. The former Emperor had been able to get an upper hand over his brother Miguel, and with every passing month it seemed like Queen Maria II's reign was surer and more stable against reactionary forces. The sources aren't always clear, but chances are that a trusted man of Pedro I's retinue commented on the possibility that, the Portuguese throne being secured for Maria, Pedro would consider a return to Brazil. The news arrived at once through personal messages to various political figures, through sailor talk at the ports, and through the shouting of the press: can the Emperor be restored? The legitimate Emperor, Pedro II, led a quiet boyhood, mostly enclosed in the Palace of São Cristóvão; Bonifácio as his guardian, inevitably quiet yet never completely stray from the political talk going on in the Court. Many discuss Bonifácio's role in the final half of the First Regency; while the Father of Brazilian Independence had a widely recognized important task in tutoring the child-Emperor, there has been speculation that Bonifácio's aura alone would be enough to assuage the deepest concerns of Liberals, even though his adopted policies as a Conservative Regent (or counsel to it) could have been very similar. Yet many also saw in Bonifácio the shrewd politicking of saying nothing and doing nothing; no matter how harsh the political storms, or backlash against measures by the government, or fiery speeches in the Chamber, Bonifácio maintained peaceful neglect towards most issues until the arrival of Pedro I's purported thoughts of restoration.

Pedro and Miguel fight for the Portuguese throne in French caricature; on the other side of the Atlantic, the Empire watched carefully as the restoration of the former Emperor became feasible

The year of 1834 began with careful Conservatives, nervous Liberals and an overall sense of dread on the streets. The First Regency has been able to secure the helm of State. The economic and trading reports looked on the upside, particularly out of regions unaffected by political trouble such as Minas Gerais or Bahia - outside of Salvador. The tight control over the Empire's finances, in which Barbacena gained the upper hand over Vasconcelos' ambition, allowed for a lowering of the external debt, which was the positive counterbalance to the tax reform of 1832 - even then, revenues dropped over 5,7% in 1833, which puckered the national projects of liberals and showed just how dependent the central government was to provincial taxation. The second wedge had been driven into the diarchy. Vasconcelos's rhetoric had been moderated greatly since his days in the Deputies, however the same general impulses continued to drive him, in that the Brazilian Empire should follow the British model. Therefore, his goals depended on a major reform of political institutions that guaranteed a framework for expansionism (which required public investment) and further representation of local concerns; the flawed framework of parliamentarianism that the Constitution of 1824 offered was not enough to ease the tidal wave of centralism that he and Barbacena had been promoting. Being of a much more modern and politically active persuasion than his Senate-raised peer, Vasconcelos also saw in these overtly one-sided concerns the shadow of autocracy: what if the Moderating Power, working legitimately within such a system, should come to crush dissent in all forms? What if Pedro I's perceived authoritarianism had not been a flaw of the man himself, but of the structure in which he had been operating? Vasconcelos held the confidence of a plurality of the Deputies, being able to work out his influence over most Conservative ones. Could he do something with it - perhaps by rallying those across the aisle?

Outside of the careful watch of the Executive, both the liberal press and the corridors of the incipient salon scene of Rio began talking much more loudly than two years ago: they questioned, at which price had such calmness descended? Were the lives of Recifenses and Imperial soldiers spent needlessly, over something Britain would decide on? Is it possible that a giant and diverse Empire could be ruled from its centre, as the current powerholders believed? Furthermore... what about the news from Portugal? Will Pedro I be once again on Brazilian shores? Is Brazil slowly sliding back in time?...

****

REFERENCES

BERRANCE DE CASTRO, Jeanne. The Citizens' Militia: the National Guard (1831-1850)

SOARES, Rodrigo Goyena. Professional stratification, economic inequality and social classes in the Empire

SEIDL, Ernesto. The formation of an Army in the Brazilian way

RAIOL, Domingos Antonio. Political Riots (1821-1835)

BONAVIDES, Paulo. Federalism and the reviewing of a State form

BERRANCE DE CASTRO, Jeanne. The Citizens' Militia: the National Guard (1831-1850)

SOARES, Rodrigo Goyena. Professional stratification, economic inequality and social classes in the Empire

SEIDL, Ernesto. The formation of an Army in the Brazilian way

RAIOL, Domingos Antonio. Political Riots (1821-1835)

BONAVIDES, Paulo. Federalism and the reviewing of a State form

****

This is a large one, I know. There are two upcoming questions in the next few days. You probably can guess at least one of them.

- 2

Nasty situation up in Recife, definitely a sour victory.

I can see that abolitionism is going to be a topic of conversation but I wonder how many will be willing to talk. Especially since landowners are defined by the number of slaves they have.

Vasconcelos is wise to provoke the British...yet.

I'm curious to see how Pedro II will turn out after the regency. A return of the elder Pedro would throw a wrench into Brasilian development but we must see if he will have the stomach to usurp his son.

I can see that abolitionism is going to be a topic of conversation but I wonder how many will be willing to talk. Especially since landowners are defined by the number of slaves they have.

Vasconcelos is wise to provoke the British...yet.

I'm curious to see how Pedro II will turn out after the regency. A return of the elder Pedro would throw a wrench into Brasilian development but we must see if he will have the stomach to usurp his son.

No rest for the wicked then. Brazil is certainly in some hot water, and things don’t look to be calming down any time soon. So much for a peaceful regency! The prospect of war on two fronts is not welcome, while reactionary and particularity stirrings do not help the situation at all. I don’t see an easy way out of this impasse.

Hello to all! I would like to apologise for the lack of updates in this AAR, and, in fact, my relative absence from the forums in general. To justify: when I was about to weave the next issues and story progression in, an academic opportunity was offered to me and it has taken the brunt of my time for most of August. I have decided, then, to interrupt the story before I present the next interaction, because those would need tallying and feedback. Consider the AAR on hold, and not cancelled, however; as soon as September is through, the rhythm of things should be back to normal and allow me to pick up on it once more.  Thank you!

Thank you!