Ordenémoslo un poco que antes va la guerra con Milán.

No os preocupeis si los posts al principio son un poco esquemáticos y poco elaborados. Va cogiendo fuerza, y las guerras italianas, en especial la de la liga de Cambrai que a punto estuvo de eliminar del mapa a Venecia, están mucho mejor. Ánimo a los lectores.

Capítulo Primero: La guerra con Milán (1425-1427)

El cruel y paranoico Filippo María Visconti, Duque de Milán, se las apañó para rehacer el ducado de su padre ayudado por los condottieri Piccinino, Carmagnola y Sforza.

La ambición que le había llevado a recuperar la Lombardía, sin embargo le impulsó a tratar de apoderarse de la Romagna, comenzando por Forli, al sur de Bologna, donde era tutor del joven huerfano heredero Tebaldo Ordelaffi.

Eso era meter los pies en el jardín de Florencia, que respondió con una guerra en la que no les fue muy bien, dada la renovada capacidad militar de Milán. Ante la posibilidad de que Florencia cayera en manos de Visconti, Venecia decidió entrar en la guerra de su lado.

The successful campaigns of Philippo Maria Visconti of Milan had Venice worried. Florence was being defeated battle after battle, Zagonara, Val di Lamone, Rapallo, Anghiari. Doge Foscari wanted the war, but the council was doubtful because they feared an alliance between Visconti and Sigismund of Hungary. Finally the desperate Florentines sent Venice a plead that was also a threat: "When we refused to help Genoa, she made Visconti her Lord. If you refuse to help us, we will make him King." This threat, plus the defection of count Carmagnola, who claimed that he could defeat Visconti's armies, turned the scale to the doge's position. The Florentine League was concluded and Carmagnola was made "Capitano Generale della genti di terra" of Venetian forces.

En Venecia gobernaba por entonces el Dogo Francesco Foscari, también un ambicioso territorialista que soñaba con las hazañas del viejo Dogo Enrico Dandolo, que aún ciego dirigió a los Venecianos en la caída de Constantinopla de 1204.

Visconti cometió el error de menospreciar a Carmagnola, a quien puso por debajo de Piccinino. Carmagnola se pasó entonces con armas y bagajes al servicio de los Venecianos, que lo recibieron con los brazos abiertos y le cubrieron de dinero y títulos. Tenían ahora un general que conocía con exactitud al ejercito milanés y a sus generales, y que tenía cuentas pendientes que saldar con Piccinino. Sin embargo Carmagnola jugaba a dos barajas, quizá pensano en algún futuro cambio de bando. Un juego que los despiadados venecianos no estaban dispuestos a financiar ni tolerar.

The battle of Maclodio.

After the fall of Brescia in the hands of Venice in 1426, Milan and Venice were unable to sign a peace treaty and hostilities continued. On the 12th of October 1427 at Maclodio, the Venetian mercenary army, formed by a coalition of Venice, Ferrara, Mantua, Monferrato and Savoy was directed by Gianfrancesco Gonzaga and Niccolo da Tolentino under the general command of Carmagnola. It amounted to 18,000 cavalry and 8,000 infantry. The milanese mercenary army was formed by 12,000 cavalry and 6,000 infantry under the direction of Francesco Sforza, Niccolo Piccinino, Agnolo della Pergola and Guido Torello under general command of Carlo Malatesta. Almost all the military talent in Italy at that time was present in the battle. As it happened at the siege of Brescia, Carmagnola won the day. Reputedly he hide crossbowmen in carts and swarmed the milanese charging army with arrows, using the surprise to his advantage. After the battle, over ten thousand milanese mercenaries were made prisoners, while the rest succeeded in crossing the river Oglio, where inexplicably Carmagnola refused to pursue them and destroy them. Furthermore, Carmagnola released most of the prisoners after the battle. Obviously the venetians were not pleased with his conduct.

Several reasons have been given for Carmagnola's conduct after the battle. Some say that the other members of the league only wanted to check Visconti's rapid expansion, but were equally alarmed by the agressive policy of Venice. After the battle, the allies would have firmly opposed pressing the advantage the venetians were getting. Others blame the inactivity of Carmagnola on the treason suffered at the onset of the battle, when the Savoyans changed sides thinking that the milanese were going to win. Although this defection did not change the result of the battle, it was rewarded by Visconti by giving his daughter in marriage to Amadeo VIII of Savoy, with a dowry in territory, Vercelli and Biella. But the most popular explanation is that Carmagnola was pursuing his own interests. He did not want to defeat his former patron severely because it would had two negative effects, on one side eliminating a possible future employer and on the other side it would have made him less necessary to his venetian employers. Those were the dangers of employing the mercenary condottieri.

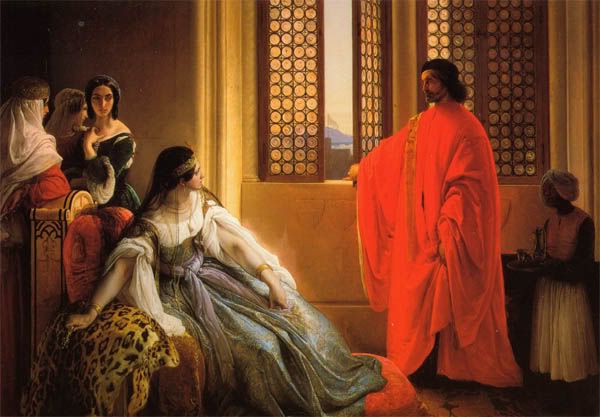

Il Conte Carmagnola

Los aficionados a la literatura quizá encuentren placer en la lectura de "Il Conte Carmagnola" by Alessandro Manzoni, tragedia teatral donde narra estos episodios. Esta es la traducción del fragmento sobre la batalla de Maclodio por William Dean Howells:

"In the Carmagnola, the action extends from the moment when the Venetian Senate, at war with the Duke of Milan, places its armies under the command of the count, who is a soldier of fortune and has formerly been in the service of the Duke. The Senate sends two commissioners into his camp to represent the state there, and to be spies upon his conduct. This was a somewhat clumsy contrivance of the Republic to give a patriotic character to its armies, which were often recruited from mercenaries and generaled by them; and, of course, the hireling leaders must always have chafed under the surveillance. After the battle of Maclodio, in which the Venetian mercenaries defeated the Milanese, the victors, according to the custom of their trade, began to free their comrades of the other side whom they had taken prisoners."

CHORUS.

On the right hand a trumpet is sounding,

On the left hand a trumpet replying,

The field upon all sides resounding

With the trampling of foot and of horse.

Yonder flashes a flag; yonder flying

Through the still air a bannerol glances;

Here a squadron embattled advances,

There another that threatens its course.

The space 'twixt the foes now beneath them

Is hid, and on swords the sword ringeth;

In the hearts of each other they sheathe them;

Blood runs, they redouble their blows.

Who are these? To our fair fields what bringeth

To make war upon us, this stranger?

Which is he that hath sworn to avenge her,

The land of his birth, on her foes?

They are all of one land and one nation,

One speech; and the foreigner names them

All brothers, of one generation;

In each visage their kindred is seen;

This land is the mother that claims them,

This land that their life blood is steeping,

That God, from all other lands keeping,

Set the seas and the mountains between.

Ah, which drew the first blade among them

To strike at the heart of his brother?

What wrong, or what insult hath stung them

To wipe out what stain, or to die?

They know not; to slay one another

They come in a cause none hath told them;

A chief that was purchased hath sold them;

They combat for him, nor ask why.

Oh, disaster, disaster, disaster!

With the slain the earth's hidden already;

With blood reeks the whole plain, and vaster

And fiercer the strife than before!

But along the ranks, rent and unsteady,

Many waver--they yield, they are flying!

With the last hope of victory dying

The love of life rises again.

At the feet of the foe they fall trembling,

And yield life and sword to his keeping;

In the shouts of the victors assembling,

The moans of the dying are drowned.

All around I hear cries of rejoicing;

The temples are decked; the song swelleth

From the hearts of the fratricides, voicing

Praise and thanks that are hateful to God.

"At the tent of the great condottiere. Count Carmagnola is speaking with one of the Commissioners of the Venetian Republic, when the other suddenly enters:"

Comm. 1: My lord, if instantly you haste not to prevent it, treachery shameless and bold will be accomplished, making our victory vain, as't partly hath already.

Count: How now?

Comm. 1: The prisoners leave the camp in troops! The leaders and the soldiers vie together to set them free; and nothing can restrain them saving command of yours.

Count: Command of mine?

Comm. 1: You hesitate to give it?

Count: 'T is a use, this, of the war, you know. It is so sweet to pardon when we conquer; and their hate is quickly turned to friendship in the hearts that throb beneath the steel. Ah, do not seek to take this noble privilege from those who risked their lives for your sake, and to-day are generous because valiant yesterday.

Comm. 1: Let him be generous who fights for himself, my lord! But these--and it rests upon their honor-- Have fought at our expense, and unto us belong the prisoners.

Count: You may well think so, doubtless, but those who met them front to front, who felt their blows, and fought so hard to lay their bleeding hands upon them, they will not so easily believe it.

Comm. 1: And is this a joust for pleasure then? And doth not Venice conquer to keep? And shall her victory be all in vain?

Count: Already I have heard it, and I must hear that word again? 'Tis bitter; importunate it comes upon me, like an insect that, driven once away, returns to buzz about my face.... The victory is in vain! The field is heaped with corpses; scattered wide, and broken, are the rest--a most flourishing army, with which, if it were still united, and it were mine, mine truly, I'd engage to overrun all Italy! Every design of the enemy baffled; even the hope of harm taken away from him; and from my hand hardly escaped, and glad of their escape, four captains against whom but yesterday it were a boast to show resistance; vanished half of the dread of those great names; in us doubled the daring that the foe has lost; the whole choice of the war now in our hands; and ours the lands they've left--is't nothing?

Think you that they will go back to the Duke, those prisoners; and that they love "him", or care more for "him" than "you"? that they have fought in "his" behalf? Nay, they have combatted because a sovereign voice within the heart of men that follow any banner cries, "Combat and conquer!" they have lost and so are set at liberty; they'll sell themselves-- O, such is now the soldier!--to the first that seeks to buy them--Buy them; they are yours!

Comm. 1: When we paid those that were to fight with them, we then believed ourselves to have purchased them.

Comm. 2: My lord, Venice confides in you; in you She sees a son; and all that to her good and to her glory can redound, expects shall be done by you.

Count: Everything I can.

Comm. 2: And what can you not do upon this field?

Count: The thing you ask. An ancient use, a use dear to the soldier, I can not violate.

Comm. 2: You, whom no one resists, on whom so promptly every will follows, so that none can say, whether for love or fear it yield itself; you, in this camp, you are not able, you, to make a law, and to enforce it?

Count: I said I could not; now I rather say, I "will" not! No further words; with friends this hath been ever my ancient custom; satisfy at once and gladly all just prayers, and for all other refuse them openly and promptly. Soldier!

Comm. 1: Nay--what is your purpose?

Count: You will see anon.

[To a soldier who enters] How many prisoners still remain?

Soldier: I think, my lord, four hundred.

Count: Call them hither--call the bravest of them--those you meet the first; send them here quickly. [Exit soldier]

[The prisoners enter]

Count: Who was it, that made you prisoners?

Prisoner: We were the last to give our arms up. All the rest were taken or put to flight, and for a few brief moments the evil fortune of the battle weighed on us alone. At last you made a sign that we should draw nigh to your banner,--we alone not conquered, relics of the lost.

Count: You are those? I am very glad, my friends, to see you again, and I can testify that you fought bravely; and if so much valor were not betrayed, and if a captain equal unto yourselves had led you, it had been no pleasant thing to stand before you.

Prisoner: And now shall it be our misfortune to have yielded only to you, my lord? And they that found a conqueror less glorious, shall they find more courtesy in him? In vain, we asked our freedom of your soldiers--no one durst dispose of us without your own assent, but all did promise it. "O, if you can, show yourselves to the Count," they said. "Be sure, he'll not embitter fortune to the vanquished; An ancient courtesy of war will never be ta'en away by him; he would have been rather the first to have invented it."

Count: [To the Commissioners] You hear them, lords? Well, then, what do you say? What would you do, you?

[To the prisoners] Heaven forbid that any should think more highly than myself of me! You are all free, my friends; farewell! Go, follow your fortune, and if e'er again it lead you under a banner that's adverse to mine, why, we shall see each other.

[To the Commissioners] I never will be merciful to your foes till I have conquered them.

La paz fue firmada poco después de la batalla de Maclodio, y Venecia logró su última gran expansión.

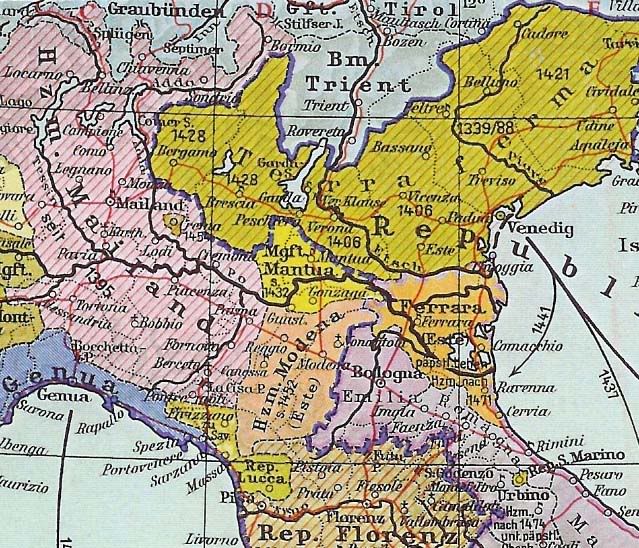

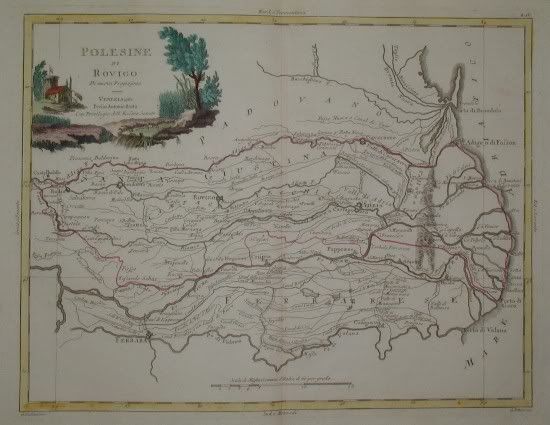

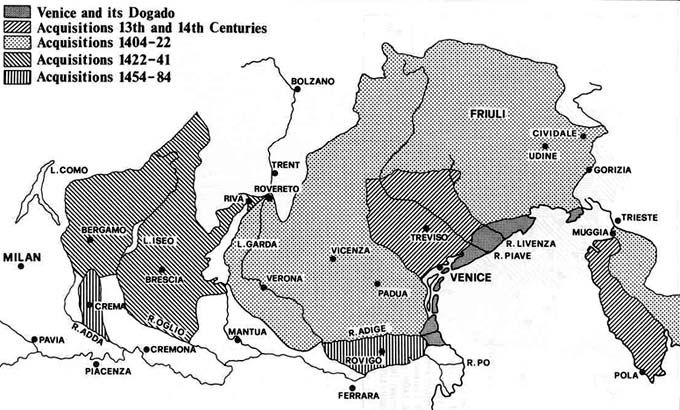

En este mapa se puede apreciar la gran porción de territorio ganada por Venecia en esta guerra, que llevó sus fronteras casi hasta las puertas de Milán. Son los territorios de Brescia y Bérgamo, marcadas en el mapa con la fecha de 1428, en que se firmó el tratado de paz que las reconocía como Venecianas.

-------------------------------------------

El juicio de Carmagnola

The first Venetian campaign had ended in the acquisition of Brescia and the Bresciano by Venetian troops, but not by Carmagnola. He had no sooner brought his forces under Brescia than he asked leave to retire for his health to the Baths of Abano; and his conduct from the very first roused suspicions. The second campaign gave Bergamo to the victorious Republic. But the suspicions of Venice were increased by finding that the Duke of Milan was in communication with Carmagnola and was prepared to conclude a peace through him as intermediary, suspicions confirmed by the dilatory conduct of their general after the victory at Maclodio (1427), when nothing lay between him and Milan. At the opening of the third campaign against Visconti, the Republic endeavoured to rouse their general to vigorous action by raising his emoluments and promising him immense fiefs including the lordship of Milan, if he would only crush the Duke and take his capital. But it was to the interest of Carmagnola, as indeed to all other soldiers of fortune, to make the operations last as long as possible, to avoid decisive operations, and to liberate all prisoners quickly. At the same time Carmagnola was perpetually receiving messengers from Visconti, who offered him great rewards if he would abandon the Venetians. The general trifled with his past as with his present employers, believing in his foolish vanity that he held the fate of both in his hand. But the Venetians were dangerous masters to trifle with, and when they at last lost all patience, the Council of Ten determined to bring him to justice. Summoned to Venice to discuss future operations on the 29th of March 1432, he came without suspicion. He was received with marked honour. His suite was told that the general stayed to dine with the Doge and that they might go home. The Doge sent to excuse himself from receiving the Count on the score of indisposition. Carmagnola turned to go down to his gondola. In the lower arcade of the palace he was arrested and hurried to prison. He was brought to trial for treason against the republic.

El tribunal condenó a Carmagnola a ser ejecutado públicamente por decapitación en la mañana del 5 de Mayo de 1432 en la plaza de San Marcos. No cabe duda de que fue un ejemplo para sus otros condottieri de que la Serenísima no permitía veleidades de aquellos que estaban a su servicio.