This game was abandoned, hard drive problems.

Prayer

Kingdom of the Franks

Île-de-France, Melun.

September, in the year of our Lord 1066

Phillipe had been praying for hours. He prayed for the wind to come and carry the Normans away to England, and he prayed for William to die at sea. He crossed himself as he stood up. He was barely fourteen years old, and even if the Regency Council agreed to call the armies, it would be very difficult to gather half the troops that William commanded.

Messengers had been coming and going from Melun since the beginning of the month. The messages were always different:

—William has left.

—The wind hasn't come.

—William drowned at sea.

—More than 10,000 men are under his banner.

Phillipe feared the message that would announce that France was growing smaller. Everyone said the war could still last years. But the Normans, the Normans hardly ever let go of a prey once they had a grip. They were still there, since the times of Rollo, biting the north of France. Phillipe walked through the chapel and looked out at the fields around Melun.

—His Highness cannot live in the chapel.

Phillipe turned his gaze from the window and fixed it on Guido. Prince-Bishop Guido of Beauvais had his hood drawn over his head to protect himself from the cold. His hands were stained with ink and he held some parchments. Lately, his eyes were always half-closed; nights of vigil and reading were wearing them down.

—Curious that a prince of the Church would say something like that.

—Curious that the King of the Franks doesn’t know that we all have a place in the Lord’s vineyard. While it is good for a king to be pious, he must not lock himself in the cloister. He neglects his kingdom, and because of his piety, bad men rise up.

Guido knew Phillipe all too well; he sat on one of the benches ready to listen to the young man confess. Phillipe approached, kneeling:

—Hail Mary, full of grace —Phillipe whispered.

—The Lord is with thee —Guido answered.

—Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned. It has been two days since my last confession.

—What weighs on your mind, my son?

—The same that weighs on everyone’s minds and tongues: William the Bastard. I barely eat and barely sleep. I live in fear, waiting for news of his victory. I cannot help but wish for his death for the good of France.

—Not only do you offend God by becoming a murderer in your heart, but you also fail your fellow men. What would men say if they knew the son of King Henry prays for such a thing? They would say: “Look at what a small man. See how he trembles in the shadows before a bastard.” And because of that weakness, men would be willing to strip you of your crown... Surely some would resist that injustice, and war would come.

—I do not fear war.

—Perhaps you do not. A king must be brave. But think of the wolves that stalk France. Once the bad men turn against you, the wolves will pounce on France. And so, because of you, how many thousands will die, and how many thousands will be pushed into hunger, anguish, and despair? Few things push a man to sin like despair. A hungry man will not hesitate to cut his neighbor’s throat for a crust of bread. Few things bring hunger like war. Is that what you want, Phillipe, King of the Franks? To condemn your people to hell?

—No... that is not what I want —Phillipe felt overshadowed—. What can be done then? I cannot pray to be spared from the bastard, nor can I lead us to war.

—You can trust in God, who cares for the beasts of the forest; how much more will He not care for France? I would impose thirty Hail Marys as penance, but luckily I’m sure it would be a joy for you —Guido looked as a smile appeared on Phillipe’s face. He was a child, a boy of barely fourteen years—. I impose thirty Hail Marys... but not here. Make a pilgrimage to Reims and say them at the main altar. On the way, visit towns, villages, castles, and monasteries. Wherever you are, listen to your people and give them something else to talk about. You are in France; William is not.

—My God, I repent with all my heart for having offended you by becoming a murderer in my heart and for neglecting my duties to my subjects.

—May God grant you forgiveness and peace. And I, in the name of Christ and His Holy Church, absolve you of your sins —Guido stood, making the sign of the cross over the kneeling king—. In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Phillipe stood up, not without first kissing the bishop’s hand. Guido watched him turn just before leaving the chapel:

—You say William is not here. Has the wind come?

—No, the wind has not come.

—Then William is in France, even if he is in Normandy —said Phillipe, looking at him.

—That’s right, William is in France.

—You also said... —Phillipe hesitated. How was it possible that he had less trouble confessing to being a murderer in his heart than saying this other thing? Finally, piety won—. You also said .... few things push a man to sin like despair...

—Did you save something to confess? —Guido looked at Phillipe’s red ears. He was still a boy—. I ask you now as your chancellor, and I believe friend: any girl?

—No... no... none... but I... can’t help it when I sleep...

—You won’t be the first nor the last man to do that. When you return from Reims, you will have a second confession and a second penance —he said, showing the same seriousness as when he scolded him for bad Latin. The boy caught the hint: a minor sin could wait.

Phillipe gave a half smile, somewhat embarrassed, and hurried away. Just as he did when pretending not to see the terrible handwriting, he thought he had gotten away with it. Guido stayed watching him. The best thing was for him to go to Reims, to stay there for a while. William had more than 10,000 men under his banner, and if the wind did not come in time to earn his own crown... he was already conspiring with the Duke of Aquitaine.

Messengers had been coming and going from Melun since the beginning of the month. The messages were always different:

—William has left.

—The wind hasn't come.

—William drowned at sea.

—More than 10,000 men are under his banner.

Phillipe feared the message that would announce that France was growing smaller. Everyone said the war could still last years. But the Normans, the Normans hardly ever let go of a prey once they had a grip. They were still there, since the times of Rollo, biting the north of France. Phillipe walked through the chapel and looked out at the fields around Melun.

—His Highness cannot live in the chapel.

Phillipe turned his gaze from the window and fixed it on Guido. Prince-Bishop Guido of Beauvais had his hood drawn over his head to protect himself from the cold. His hands were stained with ink and he held some parchments. Lately, his eyes were always half-closed; nights of vigil and reading were wearing them down.

—Curious that a prince of the Church would say something like that.

—Curious that the King of the Franks doesn’t know that we all have a place in the Lord’s vineyard. While it is good for a king to be pious, he must not lock himself in the cloister. He neglects his kingdom, and because of his piety, bad men rise up.

Guido knew Phillipe all too well; he sat on one of the benches ready to listen to the young man confess. Phillipe approached, kneeling:

—Hail Mary, full of grace —Phillipe whispered.

—The Lord is with thee —Guido answered.

—Forgive me, Father, for I have sinned. It has been two days since my last confession.

—What weighs on your mind, my son?

—The same that weighs on everyone’s minds and tongues: William the Bastard. I barely eat and barely sleep. I live in fear, waiting for news of his victory. I cannot help but wish for his death for the good of France.

—Not only do you offend God by becoming a murderer in your heart, but you also fail your fellow men. What would men say if they knew the son of King Henry prays for such a thing? They would say: “Look at what a small man. See how he trembles in the shadows before a bastard.” And because of that weakness, men would be willing to strip you of your crown... Surely some would resist that injustice, and war would come.

—I do not fear war.

—Perhaps you do not. A king must be brave. But think of the wolves that stalk France. Once the bad men turn against you, the wolves will pounce on France. And so, because of you, how many thousands will die, and how many thousands will be pushed into hunger, anguish, and despair? Few things push a man to sin like despair. A hungry man will not hesitate to cut his neighbor’s throat for a crust of bread. Few things bring hunger like war. Is that what you want, Phillipe, King of the Franks? To condemn your people to hell?

—No... that is not what I want —Phillipe felt overshadowed—. What can be done then? I cannot pray to be spared from the bastard, nor can I lead us to war.

—You can trust in God, who cares for the beasts of the forest; how much more will He not care for France? I would impose thirty Hail Marys as penance, but luckily I’m sure it would be a joy for you —Guido looked as a smile appeared on Phillipe’s face. He was a child, a boy of barely fourteen years—. I impose thirty Hail Marys... but not here. Make a pilgrimage to Reims and say them at the main altar. On the way, visit towns, villages, castles, and monasteries. Wherever you are, listen to your people and give them something else to talk about. You are in France; William is not.

—My God, I repent with all my heart for having offended you by becoming a murderer in my heart and for neglecting my duties to my subjects.

—May God grant you forgiveness and peace. And I, in the name of Christ and His Holy Church, absolve you of your sins —Guido stood, making the sign of the cross over the kneeling king—. In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Phillipe stood up, not without first kissing the bishop’s hand. Guido watched him turn just before leaving the chapel:

—You say William is not here. Has the wind come?

—No, the wind has not come.

—Then William is in France, even if he is in Normandy —said Phillipe, looking at him.

—That’s right, William is in France.

—You also said... —Phillipe hesitated. How was it possible that he had less trouble confessing to being a murderer in his heart than saying this other thing? Finally, piety won—. You also said .... few things push a man to sin like despair...

—Did you save something to confess? —Guido looked at Phillipe’s red ears. He was still a boy—. I ask you now as your chancellor, and I believe friend: any girl?

—No... no... none... but I... can’t help it when I sleep...

—You won’t be the first nor the last man to do that. When you return from Reims, you will have a second confession and a second penance —he said, showing the same seriousness as when he scolded him for bad Latin. The boy caught the hint: a minor sin could wait.

Phillipe gave a half smile, somewhat embarrassed, and hurried away. Just as he did when pretending not to see the terrible handwriting, he thought he had gotten away with it. Guido stayed watching him. The best thing was for him to go to Reims, to stay there for a while. William had more than 10,000 men under his banner, and if the wind did not come in time to earn his own crown... he was already conspiring with the Duke of Aquitaine.

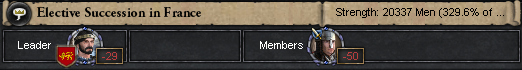

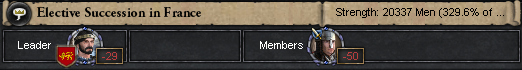

An elective monarchy after Phillipe’s death, God willing it will be many years from now said the conspirators. The nobles would choose the next King of the Franks. He doubted William would be willing to wait many years, or the Duke Robert of Burgundy, who had already killed men of his own blood.

Guido pulled his hood tighter; that cold was killing him. He feared someone would encourage Phillipe, any of the many ambitious and disloyal lords, the little kings of all France. A war could end the crown. The resources of the Île-de-France were too limited. Guido knelt before the cross and prayed. He asked for time, time for Phillipe, time for himself. He asked forgiveness for imposing a penance that in truth fulfilled his wishes to keep the boy away. He asked that the wind come and carry the Normans to England. He could not help but ask also that William drown at sea.

Last edited:

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)