Do not always judge the power or influence of a state by it's size, sometimes these looks deceive. Here on the river Main lies the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt. From the ancient times of the Merovingians and the Carolingians through to the formation of the Holy Roman Empire and to the present, Frankfurt has known mostly peace, growth, and freedom in a world defined by rapacious power struggles and perpetual destitution. Frankfurt's power, and survival, has come from its status as a chief financial center of Europe and it will likely guide it's future.

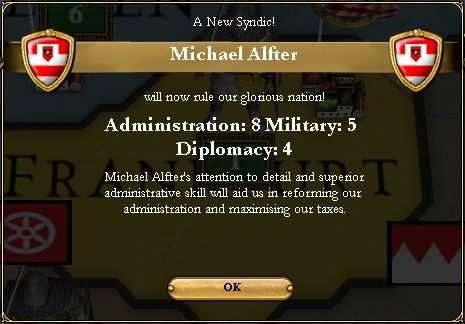

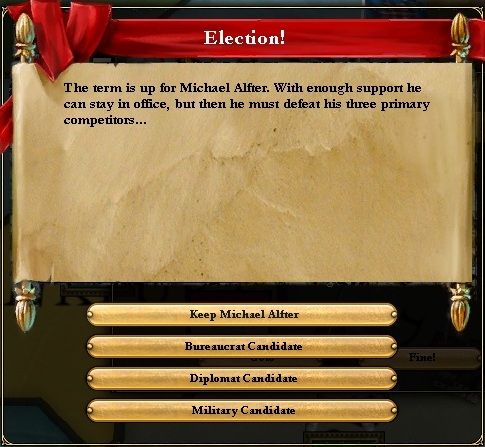

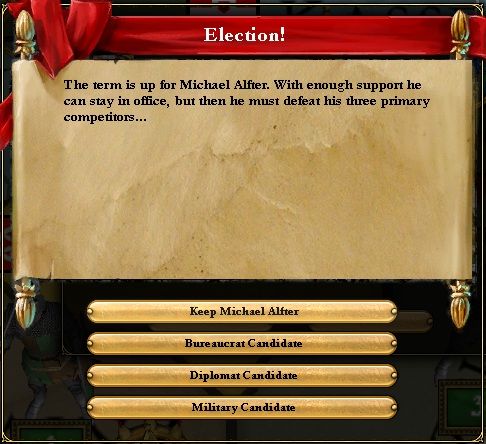

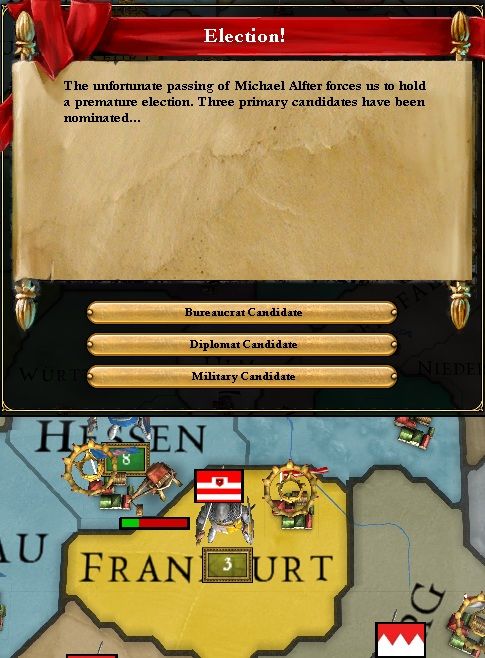

By October of 1399, Frankfurt's councilors had become absolutely determined to see their city's treasury reserves strengthened, and it was apparent that Stadtholder Michael Alfter's political survival depended on his ability to fulfill this ambition. Although such things as "political survival" rarely seemed to truly influence Alfter. He was a dangerous combination of a man, not simply for his gifted administrative abilities and shrewd political instincts, but for his clear sense of civil duty. In a continent where nobles would launch brutal wars amongst even their own family for meer parcels of land at the remorseless expense of peasants, Alfter stood out as a living paradox of the times; determined to improve the lives of his citizens and to see his lovely Frankfurt flourish.

Frankfurt already had a minor established trade presence in Antwerpen and Lubeck but Alfter was convinced that Frankfurt's trade not only held potential to be strengthened but critically needed strengthening for the city to have true strength and security. This fearful motive drove Alfter's political actions, and he wasted no time acting. He had managed to negotiate an increase in minting with Frankfurt's petty bankers which, while it would lead to some inflation, would help finance an effort to establish a strong trade presence in the wealthy Lubeck markets.

By the summer of 1400, Lubeck was thoroughly dominated by Frankfurt's traders and merchants. Alfter, already by autumn, was contemplating financing new trade expeditions. The stunning successes of his trade push into the Lubeck markets had left him, for the first time, unsure how to proceed. Just how far could the tentacles of Frankfurt's trade reach? How strong was his little Frankfurt? Maybe it was possible to become the strongest trade presence in all northern Europe?

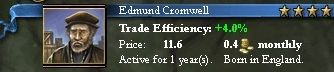

Whatever the answer was, he had decided he would not do it alone. He had arranged a meeting with Edmund Cromwell, one of the prominent traders in Europe. Cromwell had fallen out of favor with many mercantile and noble factions in England and exiled himself to the European mainland. He had actively watched Frankfurt's power play in the Baltic markets and became immediately intrigued by the city. Cromwell and Alfter had had similar thoughts; Cromwell too thought Frankfurt could achieve supremacy over the northern markets. But Cromwell went farther yet. He believed if Frankfurt could succeed in controlling the northern trade, it could just as well begin to establish itself in the lucrative mercantilist markets of Italy. Alfter's credibility was regarded highly by the traders, bankers, and people of Frankfurt and he had little trouble subsidizing a merchants' venture into the Dutch markets in Antwerpen.

The beginning of the year 1401 saw Frankfurters dominating the Baltic and Dutch markets, bringing substantial new revenue to the city-state. However,even with that new revenue, Alfter's expensive trade initiatives were taking substantial bites out of the treasury. He had convinced the bankers of Frankfurt to mint even more money but he would still have to scale down his push into France's Parisian markets, and even then the treasury would be almost completely dry. Nevertheless he pushed forward inspired by the previous triumphs and created incentive for a market push into Paris in the summer of 1401.

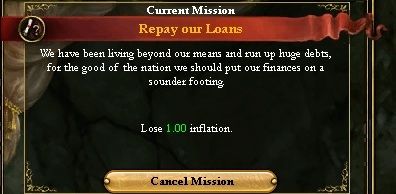

The winter brought disaster. The costly trade initiative had almost completely failed to establish any Frankfurtian financial presence in Paris. The war between the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of France was wrecking the Parisian economy and with the successful capture of the entire northern coast of France, Paris itself was severely threatened and unlikely to withstand an assault from the Emperor's armies. Alfter was shaken. He had subsidized an expensive failure, left Frankfurt with no reserves for the near future, and his mandate to create a strong reserve was going to fail and likely lead to deposition. Edmund Cromwell was not as gloomy as Alfter. Perhaps because it was not his own political office or home city that was in question, or maybe it was simply because he was experienced. He offered a simple solution.

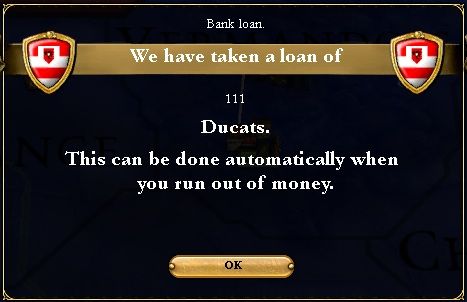

Cromwell knew that the reputation of Frankfurt's traders and bankers and the city's treasury itself was still strong and he could easily secure any kind of loan available in Europe. Alfter could not only fund more trading with a good loan, he could also set aside enough for the substantial reserve that the electorate had mandated. The revenue from the growing trade in the meantime would easily fund the interest payments and the final sum of the loan in 5 years.

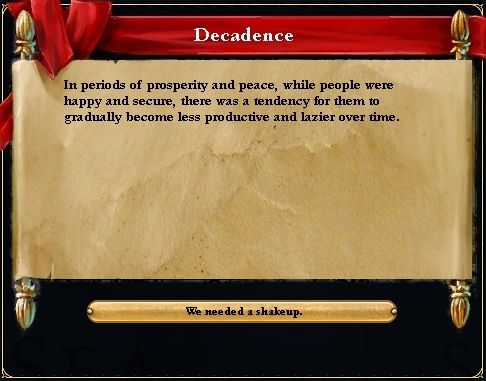

France's armies had miraculously succeeded in defending Paris and began dislodging the Holy Roman Emperor from Caux in the spring of 1402. There was a change in the environment in Paris, a sense of security finally, and Frankfurters now found it easier to do business than before. By summer's end, Paris's markets were run by Frankfurtian companies and trade families. More importantly, all the major trade centers of Northern Europe were firmly in Frankfurt's control. Alfter had successfully secured a sizable treasury reserve for Frankfurt and the city council was beginning to trust utterly in their statdholder. But, as with any political assembly, the city council's motives were not always driven by caution or reason. The city council mandated that Alfter use Frankfurt's deep pockets to expand the size of the army so that it was larger than it's neighbor Mainz. It was clearly a jingoistic demand, more likely driven by the need to fill the councilors vote rolls than a desire to preserve Frankfurt's independence. Frankfurt was at the height of peace and prosperity, Alfter decided he would have nothing to do with any such effort, and simply left the council resolution sitting on his table, unopened.

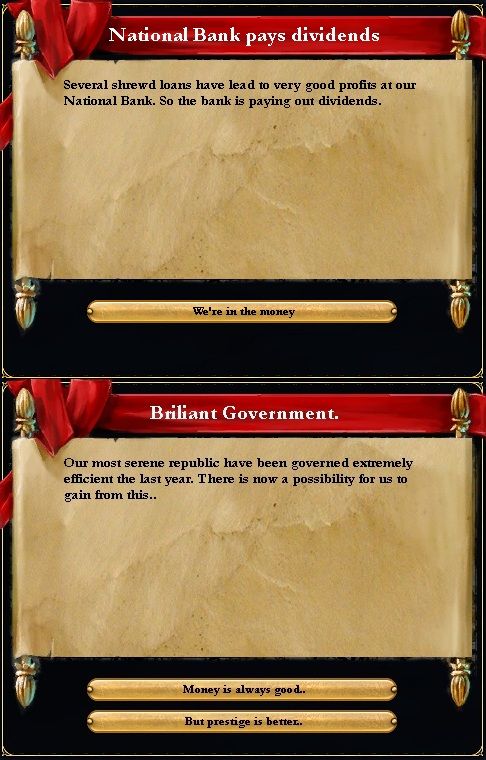

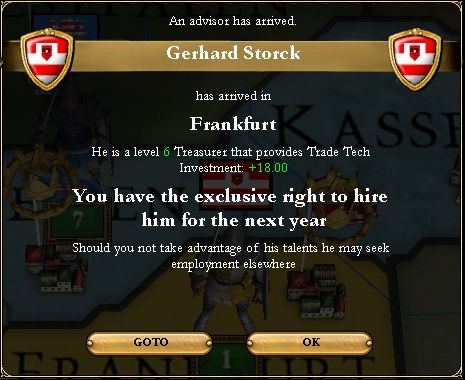

The winter of 1402 proved to be one of the most productive in recent times. Frankfurt's seemingly unstoppable ability to bring in new trade revenues and reliability in the loan markets made it a hotspot for Europe's financiers. With a vote of confidence from his trusted adviser Cromwell and the guaranteed support of the city council, Alfter established Frankfurt's first national bank, greatly empowering Frankfurt's ability to finance it's trade and augment inflation. The complete domination of the northern markets was acknowledged internationally when The Hansa formally invited Frankfurt into their trade league. Perhaps the next year would have finally been a year of rest and relief for Alfter were it not for the other things on his mind.