Hi guys, there was a delay on the move so everything is behind schedule. One thing that means is I'm going to be without internet for the near future. As such I've produced a bumper Appendix chapter (in no way mimicking my good friend

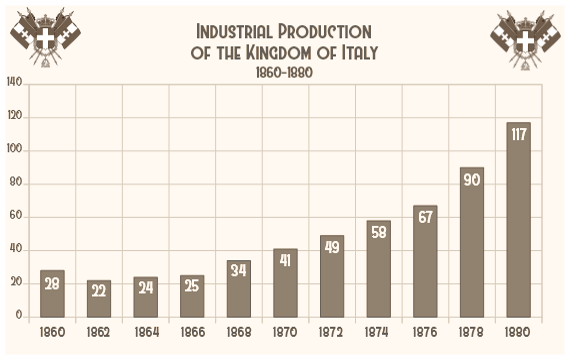

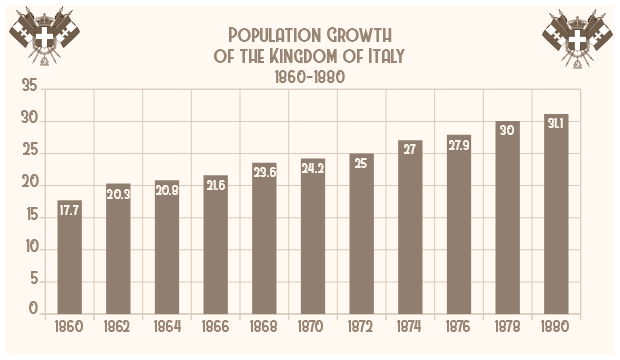

@RossN). I had originally intended this to be a two-parter but as I don't know when I'll be back I thought I'd dump it here in one big ole' pile. Its low on pictures and I've only just realised information regarding the military. I'll try to correct once I'm back up and running. Until then I hope you enjoy this overview of

la Patria in 1880.

Thank you stnylan, sorry I didn't respond to this message earlier.

So the scramble for Africa has well and truly begun.

It has indeed, we're only just getting started.

So the scramble begins. It sounds like France is losing out, at least compared with real life.

I love the personal touches - a pet python for the win!

Overall frankly yes but I blame that on the ramshackle junta running the place. We may have taken Tunisia but you also have Spain getting uppity.

Thank you, it's always nice to dig up historical oddballs when writing AARs.

I purposely left that out, the Congo and East Africa will get there own chapter.

I knew I'd have to catch up on a few things after being away, but I genuinely never believed that it would be Jape (Jape mark you!) who would race ahead.

You, and Italy, have moved on decades and mostly to the good. The Fly River Expedition is an odd corned of history I am glad you brought to our attention and, as always, I enjoy any mention of the White Rajah's of Borneo (apart from general barkingness, I have something of a soft spot for Badger based coats of arms).

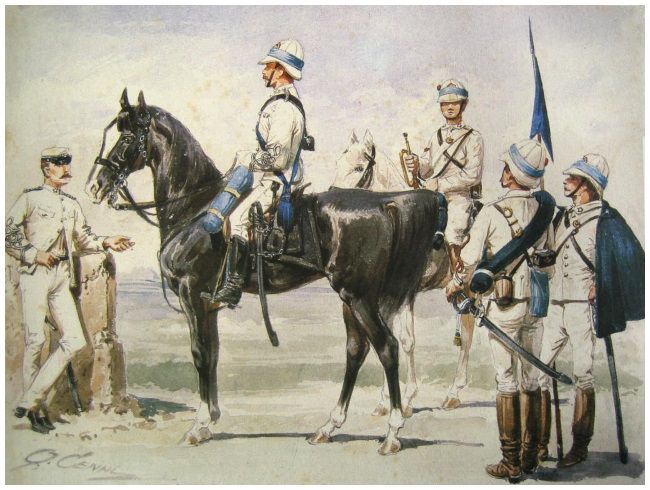

Blanc played a mediocre hand very well at Lisbon, Italy will have her East African Empire it seems. You also appear to be hinting that Italy will avoid it's humiliating defeat to Ethiopia, certainly if there is a war you are not setting it up for the heroic victory Ethiopia historically managed. I look forward to seeing how this turns out and who, if anyone, the Ascari end up fighting for and against.

Will wonders never cease Pip old boy!

Moved on in some ways but not others as I hope this addendix will shed some light on. I stumbled across the Fly River jaunt and knew I had to put it in somewhere. The Brookes are a fascinating little bit of history themselves. We may pop back to Borneo yet.

Blanc did very well (he eventually became foreign minister IOTL) however a gentlemen's agreement does not trump boots on the ground, East Africa isn't ours just yet. I hinted that we would likely clash with the King of Kings but Ethiopia was never kind to Italian soldiers, have to wait and see. Oh don't worry the Ascari in some form will be making an appearance fairly soon.