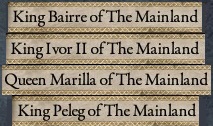

These characters have Arthurian names, but their tale isn't conflated with Arthur's. Is this narrative segment a view of what actually happened or a legend from later times?

Why was Mabel renamed Morgan? Symbolism? To confuse future historians?

Why was Mabel renamed Morgan? Symbolism? To confuse future historians?