I'm not sure he really is that unreliable. The sagas have inconsistencies too, e.g. the two we discuss here have differing descriptions of when Erik the Red died. And given the various stories were composed by different people and possibly even at different times, then inconsistencies are to be expected. And it is my impression that he generally is very trustworthy and fit with other sources where they exist. I know it's the case at the very least for the last 50-60 yeras he covers, but it was my impression that also was the case for the earlier parts.Saxo is an inconsistent source. Sometimes his material is verifiable via other sources. But sometimes he writes conflicting information about the same historical figures within the body of his own works. Perhaps this is reflective of the oral tradition and Sagas that tell stories from different perspectives.

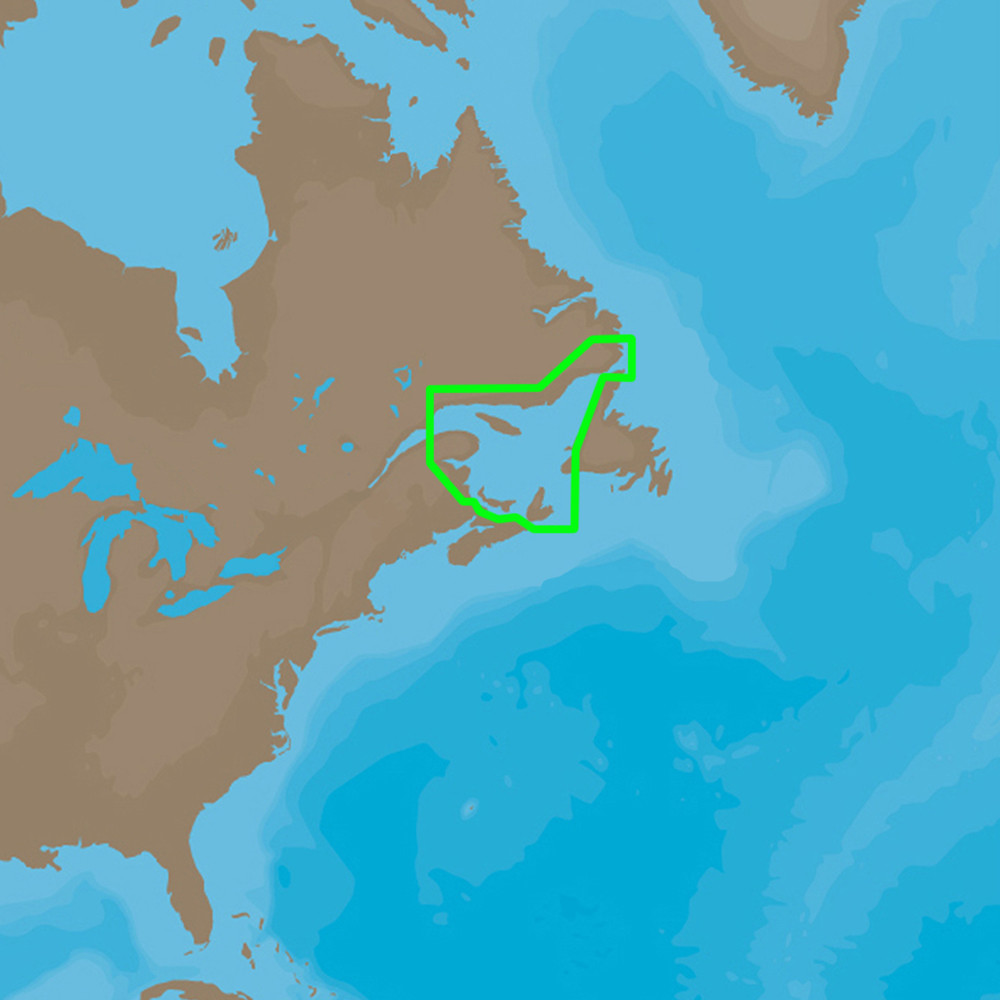

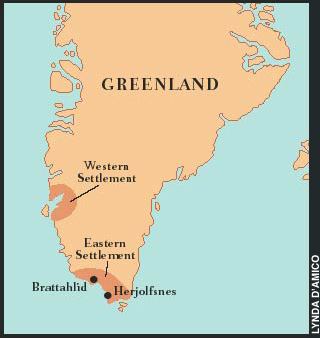

Firstly then Midwinter could be in mid Jan, as winter was mid Oct to mid Apr. I don't know whther it was mid Jan, but my copy specifically states that midsummer was midways through Summer, not when it is today at the solstice. So who knows. Though, it writes that it's when the days are shortest, not Midwinter, and that ight be significant.This is creates a tricky issue because nowadays, the sunset time in Midwinter December in Nuuk, near Greenland's Vestribygd, the Western Settlement, is 3:28 PM, and this certainly hasn't changed drastically, like more than 10 minutes, in the last 1000 years. By comparison, the sunset time in Midwinter December in Reykjavik, Iceland is 3:30 PM, and north of L'anse aux Meadows in Labrador City it is 4:12 PM. (SOURCE: https://www.sunrisesunsettime.org/north-america/canada/labrador-city-december.htm)

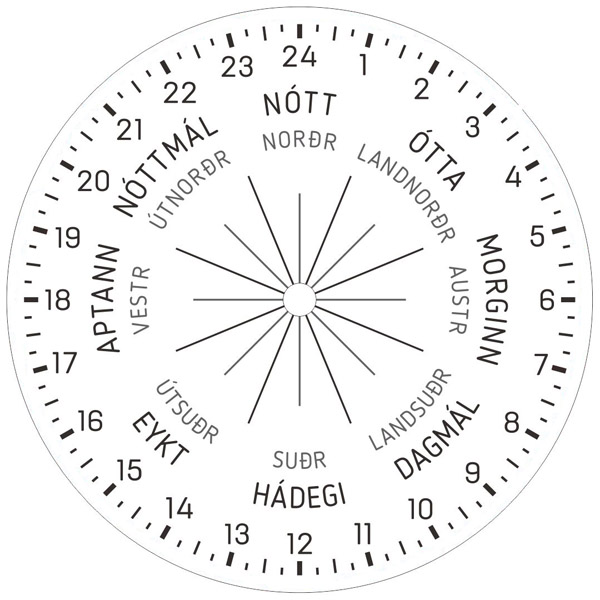

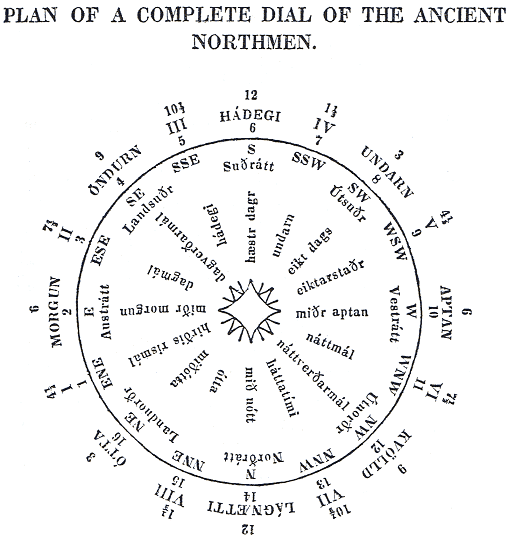

Also, look at New Glasgow. It has the Sun rise around a quarter to 8 and set around 16:30. If you only have 8 points you measure time from, then that could be taken to be dagmål and øgt, the two points in question, as that'd be the closest points. Or it could be it'd say it was in between the two.

It says that the Sun stood on the sky at those two points. It's meaningless to say that unless that's when it rose and set. And I can't read it any other way than it'd be sunrise and sunset.If the text intended to literally say that the sun was still up at 3:30-4 PM, instead of stating the time when the sun literally crossed the horizon, then it would make more sense and fit the context better. I understand that Vikings typically treated the sky line like a time-telling piece of equipment when marking the sun's spot, but maybe their wording and phrasing is also important.

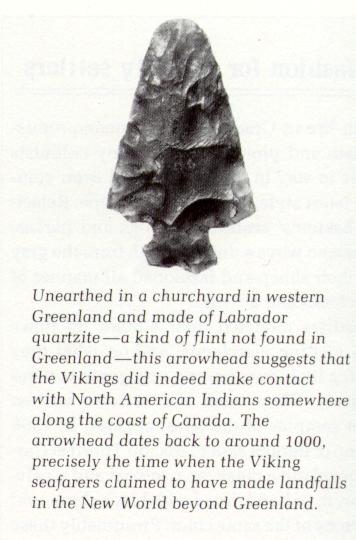

Just because they reached Baffin later doesn't mean it was Baffin they saw this one, specific time. You seem to think that whereever they first reached must be where they always kept reaching. Which needn't be the case.Right. I share your skepticism that they would have known that Baffin Island was literally an island. On the other hand, archaeologists found what they consider likely Viking artifacts in a couple spots up and down Baffin Island as I posted with the artifact map earlier in this thread. I don't know how far north the icesheet line runs in the summer on Baffin Island, but the Eskimos and Dorsets were on the north end of that island, so it seems that somehow the Vikings could have become familiar enough with the island to guess, correctly, that it's an island.

It specifically says large, flat rocks. That doesn't fit with grass, and I don't see any mention of grass and in fact that land is listed as worthlss, whihc grasslands wouldn't be.It looks like Helluland practically has to be Baffin Island for a couple reasons. First, the Vikings sailed four days to get from Helluland to Greenland. In the Vikings' boat speeds, this would be a couple hundred miles at least. In that case, we couldn't be talking about some rocky island along Greenland's coast, but something hundreds of miles away, like Baffin Island is. Likewise, Helluland wouldn't be close off the coast of Markland, because it was a three day sail to get from Baffin Island to Markland. And in real life, Baffin Island is 100 miles from Labrador, which is rather less than the 250 miles for a 4 day crossing from Greenland to Helluland. A second reason is the description of Helluland as being a flat rock land with glaciers instead of trees or grass. Some parts of Baffin Island have grass, but other parts don't and compared to Labrador, it's basically treeless. The description is a pretty good fit.

Also, again, yuo're thinking about this from a modern POV. Yes, the minimum distance from Resolution to Labrador might be long, but if they're going at sea and coming into the coast far down Labrador then the minimum distance doesn't matter.

They dint' have the geographical knowledge you do and wouldn't necessarily have taken the shortest routes.

Also remember that a day is only 12 hours, not 24. And the distance covering you have kept quoting, does that take that into account?

No, you can't necessarily do that. Old Norse is an extremely grammatical language and has lots of cases, etc. that allows you to get context and as a result word order doens't really matter much. So you can't just look at the corresponding part of the text to geuss what might be what.It sounds like you have a high quality translation. I think I'm better able to narrow down where the Danish translators might see the text as saying "crossed," ie. the phrase "beittu med lanndinu".

Unless you understand Old Norse at least somwhat you can't do that. Some of the sagas literally have things moved around completely, albeit that seems to mostly be happenign in various poems where it's taken to the extreme. But still.

Yes, and note that I'm not a professional translator, so I might not be translating what I'm reading in my copy to English the way it should be.Skilled translators can have different conclusions about how they perceive a word or a phrase.

And that is how you get poor translations. A good translation WILL translate teh meaning, not the exact words. Unless you're very familiar with the lgnauge translated from then you can't do any kind of literal translation, as you'll miss important things.First, you can choose the most precise, word for word translation of a text. Personally, I prefer that.

What does: "The man placed the wooden shoes" mean?

What does it mean if you shoot the parrot?

You said you want literal translations, so what does the two above things mean? And no Googling or in other ways looking anything up.

Now, when translating you should stay true to the source, of course, but in some cases you will need to also use stuff that makes sense to the readers. Whihc is why a good translation, like mine, will have an explanation a the back for words/terms whihc can't really be translated without an explanation as well as using footnotes.

Also, translating Old Norse to Danish presumably also is easier than going Old Norse to English, as a lot still is the same in Danish. So ythere'll be stuff that you don't ned ot explain, whereas in English you'll miss stuff. Like, in one of the quotes you gave I could see that the Old Norse talked about a fjord, but the English translation said bay...

Please don't use underlining. Use italics if you want to highlight something. Underlining is bad and a relic from the days of typewriters. I litrally hve a hard time reading the Norse you underline as it's hard to see whether a letter goes below the line or not. So please don't do that, at least if you want me to keep reading it.þa er lidin uorv tvau dægr sia þeir . lannd . ok þeir sigldu unndir lanndit . þar . var nes er þeir kvomu at þeir. beittu med lanndinuok letv lanndit aa stiorn borda.

(When two days had passed they sighted land and they sailed along the coast. There was a promontory. When they got there they tacked along the coast, keeping the land to starboard.)

And that is irrelevant. English and Greek is not Old Norse."Sailing under a land" is a real phrase in English and Greek, like in the Bible when it says in Acts 27:4:

No, it didn't. You seem to have fallen for various fallacies and at the very least are looking at things way too literally translation wise.This helped clear up the issue for me, thanks.

Where does it say that? It just says that the wind is northern. It could do in any direction, in fact, calling it a northern wind suggests it's primarily southern. So for all we know they culd ahve been blown so far south that going due west on a latitude would hit NS, not NF.Bjarni's boat was overall sailing southwest from Iceland, and then when it got to the First Land, he sailed with the land on his left side, ie. northward toward Greenland and Counterclockwise around the First Land. For Bjarni to sail from central eastern Nova Scotia to Newfoundland, he would have to tack north and east against the wind, or else wait for the wind to change into a helpful direction. Supposing that he sailed north along N. Scotia until he got to the north end of Cape Breton, he would also have to sail northeast to get to NFLD.

No wind direction is given between first and second land. Also, note, its possible they kept being abl to see the first land for a good amount of time while at sea towards the second land.

Between second and third there's a south western wind, meaning they'd be going north east. And betwen third and Greenland it's teh same winds, so that'd indicate north east still, though it does say that the winds got stronger, so while id eosnt' say it then perhaps that could indicate a change in direction.

Anyway, Baffin isn't North East of Labrador. But it is of course possibly they mostly wnt north on the south western wind. Could also be they actually hit Greenland and just a part without much vegetation and where the ice sheet isn't too visible due to the not enoug glaciers part.

What does NS in generally being flatter matter here? Like, they're not exploring the lands. They're lietrally hitting the coast in a single place and perhalf going up it for a bit. And if the NF hills are mostly inland then they'd be unablt to see them.Another difficulty is the description of the three lands. Supposing that N. Scotia was the first, wooded land with small hills, and Newfoundland was the second, flat land with woods, this description doesn't seem to match the two lands. Nova Scotia seems flatter than Newfoundland. The top end of Cape Breton is hilly, but Newfoundland is even hillier. Further, if N. Scotia and NFLD were the first two lands, then Labrador would be the third land, yet Labrador doesn't match the description of Helluland as a treeless glaciered land.

Iceland is called iceland because it initially was reached tat teh north eastern part which had big glaciers. Yet, Iceland for the most part doesn't have glaciers. Where you randomly land matters, and they could have landed anywhere on teh coastline.

Could have taken it to be part of the same land, with a straight between it.Alternately, one could theorize that Bjarni landed in N. Scotia, sailed to its north end, and then sailed straight north to the Labrador Peninsula. In that case, Bjarni would sail northeastward along the Labrador Peninsula and through the strait separating Labrador from Newfoundland. The strait is so narrow, that it's very likely that Bjarni would have seen Newfoundland, and based on his journey route, he would have to realise that it's separated from N. Scotia and from Labrador. However, the story of BJarni's journey makes no mention of a separate wooded land in that region north of his first land and southeast of his second land. On other other hand, this could conceivably be absent because the writer didn't consider it essential to mention it.

You're thinking about land too squarely here. A land needn't be an island, etc. A land easily could be both mainland and an island. Or it could be separate. Or it could be half a continent lik Særkland.

If two closely connectd areas both are similar then it might very well be that both are considered the same land.

No, you have no idea where they departed Markland. It needn't be at teh edge. Could be anywhere along it, really. You keep thinking thy need to take teh geographically shortest or most favourable route. They needn't. They don't know what you do.In any case, if one theorizes that Bjarni sailed southwest from Iceland and arrived at Newfoundland as his First Land and then at the Labrador Peninsula as his Second Land, Markland, the implication is that the Saga was counting Newfoundland and the Second Land, Markland, as separate landmasses. In that case, when the Sagas talk about the Vikings sailing southwestward or southward from Markland, the implication is that they are departing from the Labrador Peninsula, rather than from the south of Newfoundland.

No, what they knew from home wouldn't influence it like this. A hill is a hill, and what they knew at home would be fjeld anyway, not hills. Plus, you can have short ones of those too.Just looking at pictures and topographical maps, the east coast of Nova Scotia is super flat, like at Halifax, whereas Newfoundland when compared to the Vikings' homeand Iceland or Greenland would not be called very mountainy, but rather hilly. However, someone who grew up in a flat land could say Newfoundland was mountainous, which it strictly is at its west coast (ie. not the side facing Iceland that the Vikings would have traveled). The west coast's highest spot is 2,671′ft, in the southwest of NFLD. So in conclusion, the small hills description feels more likely to apply to NFLD than Nova Scotia to me, but this also feels ambiguous enough.

And those are teh three skin boats... Which proves my point. Or points, actualyl, as this also shows why you shludn't translate things this literally.This use of "hills" by Krossanes could hint that Kjalarnes and Krossanes were on Bjarni's small-hilled First Land, but not necessarily so.

Anyway, it shows that hill can be just a small mound.

This honestly feels like you're not properly reading what I'm writing. And it's not the first time. I honestly have semi tired or writing these posts as it seems like you're only half reading what I'm writing and then sometimes arguing completely differently based on something I either didn't say or only half said.Let me explain evidence that sometimes they must be giving sailing times for the open sea: First, in both Eric the Red's Saga and the Greenlanders' Saga, the Vikings sail from Markland 2 days to get to Kjalarnes and to the northward cape, respectively. It looks like far too long to sail two days from the top of Labrador to the southeast or south end from which they would have departed Labrador. So the natural conclusion is that the two days are the time when they spent starting at theirdeparture time from Markland and not including any sailing on the coast. But secondly, in those descriptions, the Sagas seem to specify that the times between Greenland, Helluland, and Markland were sailing times starting from the departure from the landmasses:

Anyway, being at sea coul ahve part of it still have land visible. In fact Bjerne mentions that both when departing Iceland and when approaching the first land.

It says that the bottom corner which is closest to the backend of the ship cases the land. That could indicate that they're going at sea, just at a differnt angle. Also having teh backend of the ship face teh land needn't mean they're going perpendicular,as you seem tyo imply.This brings up an argument that the First Land was Newfoundland, because Labrador is visible from Newfoundland:

In contrast to the two journeys above (ie. from Markland to Helluland to Greenland), when the Saga says that Bjarni arrived at the First land, they don't turn their boat's back end to the land when they start sailing, but rather they keep the land on their left side:

Bear isles (Bjarneyjar) most likely is an island group off the coast of America. If we trust the name form in the second edition of the saga, Bear Island (Bjarney) then it coiuld be the island Disko off the coast of Greenland far tot eh north.Can you quote the Danish footnote that if it's a chain of islands that it can only be the islands off America?

That'd be ploral, but the other edition has it in singular, bjarney, s they differ ther. And it's an easy mistake to make either way, so could be island to isles or isles to island. Each is trivial to make when transcribing.Grammatically, can it make sense that "Bjarneyar" would mean one island

It says they sailed along the coast and then saw ti was an island, before heading to sea. So it must have been clear somehow.So we don't get a clear message of exactly how they saw that it was an island. The impression is that they saw around it.

How so? They needn't have taken teh shrtest route. And who says they crossed up at Baffin's easternmost point?his choice of Resolution Island would force the sailing journey to Helluland from Labrador to be even shorter than we read in the Sagas and the journey to Greenland to be even far longer than a shorter journey from Baffin Island's easternmost point.

Also, again, the land Leif saw needn't have been the same Bjerne saw. There's lots of areas up thre wich have large, flat rock formations I'd imagine.

Baffin island only is an island due to a narrow straight.To expand on the Island issue:

First, I sympathize with your idea about Helluland being smaller than Baffin Island, because just taking the story by itself without reference to a real world map of that area, I would imagine that it was describing an island like the size of a Hawaiian island or Disko Island laying midway between Labrador and Greenland.

Second, if the Vikings landed on Helluland and it was a sea-island within full eyesight of a bigger coastline like the treeless Baffin Island, then I would expect that the author would tend to give notice to that much bigger landmass, like when Eric the Red's Saga mentioned the Vikings seeing Bjarney off the coast of the wooded Markland, or the Greenlanders' Saga mentioned the dew island off the northward cape.

Third, the Greenlanders' Saga, it says that the Vikings only saw that Helluland was an island after sailing away from the island, not on their approach to the island. This suggests a limited number of possibilities:

(A) Helluland was a coastal "barrier sea-island" by a giant landmass like Baffin Island, and the Vikings couldn't see if the island was a peninsula or not until they saw it from a few sides. But in that case, it would conflict a little with the Vikings' silence about that giant landmass.

(B) Helluland was such a medium sized island like the size of Disko Island or Ireland in the open sea out of view of any larger landmass like Baffin Island, and it was so big that the Vikings couldn't get a good enough view of its sides to see that it was an island until they left it from another side. But in that case, the problem is that there is no such island in that size range in the open sea between Labrador and Greenland.

(C) Helluland was a giant landmass, with a size like Baffin Island or Greenland or the Labrador Peninsula, and the Vikings made an evaluation (in this case a correct one) based on the sides that they saw that the landmass was an island without actually seeing all the sides of the landmass.

Fourth, in a real life 4 day journey southwest from Greenland like the Greenlanders' Saga describes Leif making from an island chain north of Nuuk, the Bjarneyar Islands, Baffin Island is the real life treeless landmass that one would arrive at.

Fifth, we can use the process of deduction to rule out alternatives. There is no treeless island laying between Greenland and Labrador that meets all of these descriptions for Helluland, like the 3/4 distance ratio for the two sailing journeys to and from Helluland. For instance, Resolution Island is the biggest island off the southeast coast of Baffin Island, but it's only ~50 miles from Labrador and 400 miles from Greenland, so it doesn't match the 3 days' journey from Markland or the 3 to 4 ration for the journeys' times.

Sixth, J. Enterline writes in his book "Erikson, Eskimos & Columbus" : "The great majoroty of scholars who have studied the Sagas have concluded that Helluland was Baffin Island." Does your Danish book have footnotes explaining about Helluland in a way that can help?

Seventh, Viking artifacts suggesting camping or settlement were found on three spots on Baffin Island, suggesting that it was a land that the Vikings were familiar with southwest of Greenland.

Eight, there is also the issue of what practical difference does identifyinf Helluland make. My larger goal is to find the Vikings' locations from Labrador and farther south. Clearly on his journey when he got blown from Iceland southwestward, Bjarni arrived at a spot from Nova Scotia north to Newfoundland north to Labrador. To me, looking at a map, the choices of Newfoundland (or conceivably Nova Scotia) and Labrador for the first two lands that Bjarni found are so obvious that it's hard to see alternatives for the second land. One couldn't realistically propose for inslance that Bjarni landed at Newfoundland first and then came to Belle Isle as the second land and then sailed to Resolution Island without mentioning Labrador's coastline.

Thanks for talking with me, @Wagonlitz

Unless you're specifically exploring it you won't see that.

Plus, it's far too large to easily see it's an island. Could be it was that and they guessed it was an island, but it could just as easily be part of the main land like how Norway isn't an island. That too could appear to be an island by your arguments, if reached around Bergen.

Also, just because they were on Baffin later needn't mean they were teh first time.

She notes it was a matter of years, so needn't be 10 years. Could be just a winter. Though, I don't know how extensive it was. The first quote talks about it being an extensive ground, so if lots of labour was put in, then perhpas it was more permanet than just a single year or two. Or at least intended for longer.One of the lead archaeologists at the L'anse aux Meadows site has been B. Wallace, and she laid out her explanation of the site's short span of Viking habitation this way:

Again, they needn't to have landed at teh same spot every time. There were no roadsigns or anything. If you reach an area looking like Markland then you'd say you'd reached Markaland, even if you reached it say 100 km down the coast from where you usually reach it.OK, the issue here is whether over time the identities of these three places would remain in the Greenlanders' memories instead of their locations getting forgotten and becoming unreliable during the transmission of the story. So it's not exactly needed that on each trip to Markland the Vikings kept taking the route through all three same spots.

And I don't see why the identities of teh places would becom unreliable over time. I doubt it did.

Like, you could have had them initially reach Resolution island and find it had large, flat rock formations. Later they rech Baffin and finds it has the same. Hence that's also a helleland. As both are close then both are part of teh same land.

The vikings weren't more illiterate than the rest of the world.even if the Vikings were often illiterate

And honestly, afaik they might even have been a bit more literate in that many knew at least some runes, afaik, but I could be wrong on that. But writing definitely wasn't any kind of unknown thing.

Some of those poems if not all of them indeed were from teh 900s/1000s and IIRC were written down. One of the oldest poems is from the early 800s or something like that, and that was written down back then, IIRC.The Sagas also retell poems that the voyagers created, so the implication at least from the Sagas is that the Vikings either had some memorization skills, or else they were able to write down their poems for the Saga writers to record.

- 1