Hello, and welcome to another week of fun unveiling of the map of Project Casar. In this week’s Tinto Maps we will be taking a look at South East Asia, so without further ado let’s get started.

Countries

Quite a variety of countries in the area. The regional power in the decades before 1337 was the Khmer Empire, although at this point they are already in decline and have lost much of their previous hegemony. On the west, the fall of the Burmese Pagan Kingdom and the following Mongol invasions gave rise to the disunited kingdoms of Pinya, Sagaing, Prome, and Toungoo, while in the south the Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy (also known as Pegu) also split apart. On the center, the decline of the old Lavo Kingdom and its subjugation to the Khmer gave way to the emergence of the Kingdom of Sukhothai when Khmer started its decline too, and Sukhothai is emerging as the dominant Thai kingdom in the area. However, Ayodhya is already gestating the rise of another great kingdom, as King Ramathibodi, the founder of the Ayutthaya Kingdom is already poised to gain power in the region. On the east coast, the Kingdom of Đại Việt is under the orbit of the Yuán, with constant conflict with the southern Hindu kingdom of Champa.

Societies of Pops

A region very rich in Societies of Pops, which will make it definitely an interesting area.

Dynasties

The dynasty of the old Pagan Empire is still alive in Prome, with many other dynasties in the region having ties with it, while the different Thai dynasties also have ties among each other.

Locations

Provinces

Areas

Unfortunately, currently the name of the sea area encroaches too much into the land (this will be fixed, don’t worry), but the blue area that gets underneath that name is Chao Phraya.

Terrain

Tropical and jungle almost everywhere, with quite a bit of comparison between the southern flatlands and the northern mountainous areas.

Development

Not as developed as the surrounding India or China, but the main centers of power (like Angkor, Pagan, and Sukhothai) are a bit more developed.

Natural Harbors

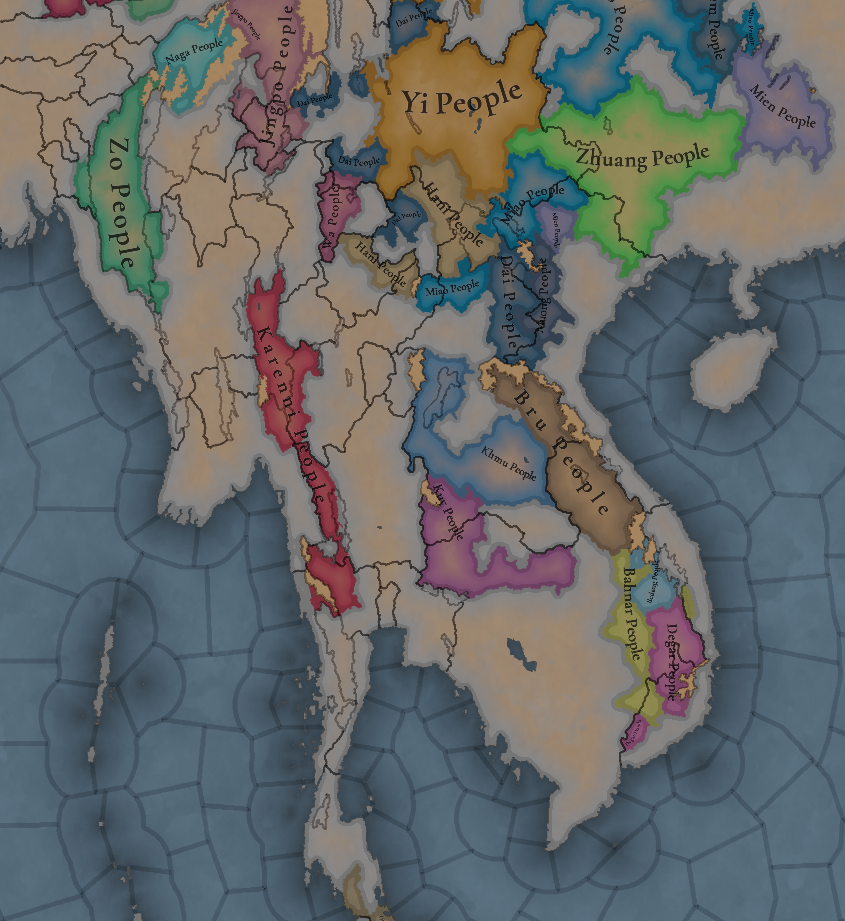

Cultures

A quite variety of cultures, although the southern areas haven’t had their minorities done yet so there will be even more variation there.

Languages

As an addition from this week one, we have a new map to show with the languages. Keep in mind that this area hasn't had any language families or dialects done yet, so there is a bit of grouping.

Religions

Again, keep in mind that minorities are not done, so there will be more variation added inside the Theravada block, as there has to be still quite a bit of Hinduism presence in Khmer (its conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism at that point was one of the causes of its decline), and quite a bit more of Satsana Phi among all the Tai peoples.

Raw Materials

Quite a variation of resources, although dominated mainly by lumber and rice.

Quite a variation of resources, although dominated mainly by lumber and rice.

Markets

The commerce is dominated by those countries benefiting from sea trade routes, but the emergence of a strong Ayutthaya Kingdom in the middle will for sure cause a change in the balance of powers.

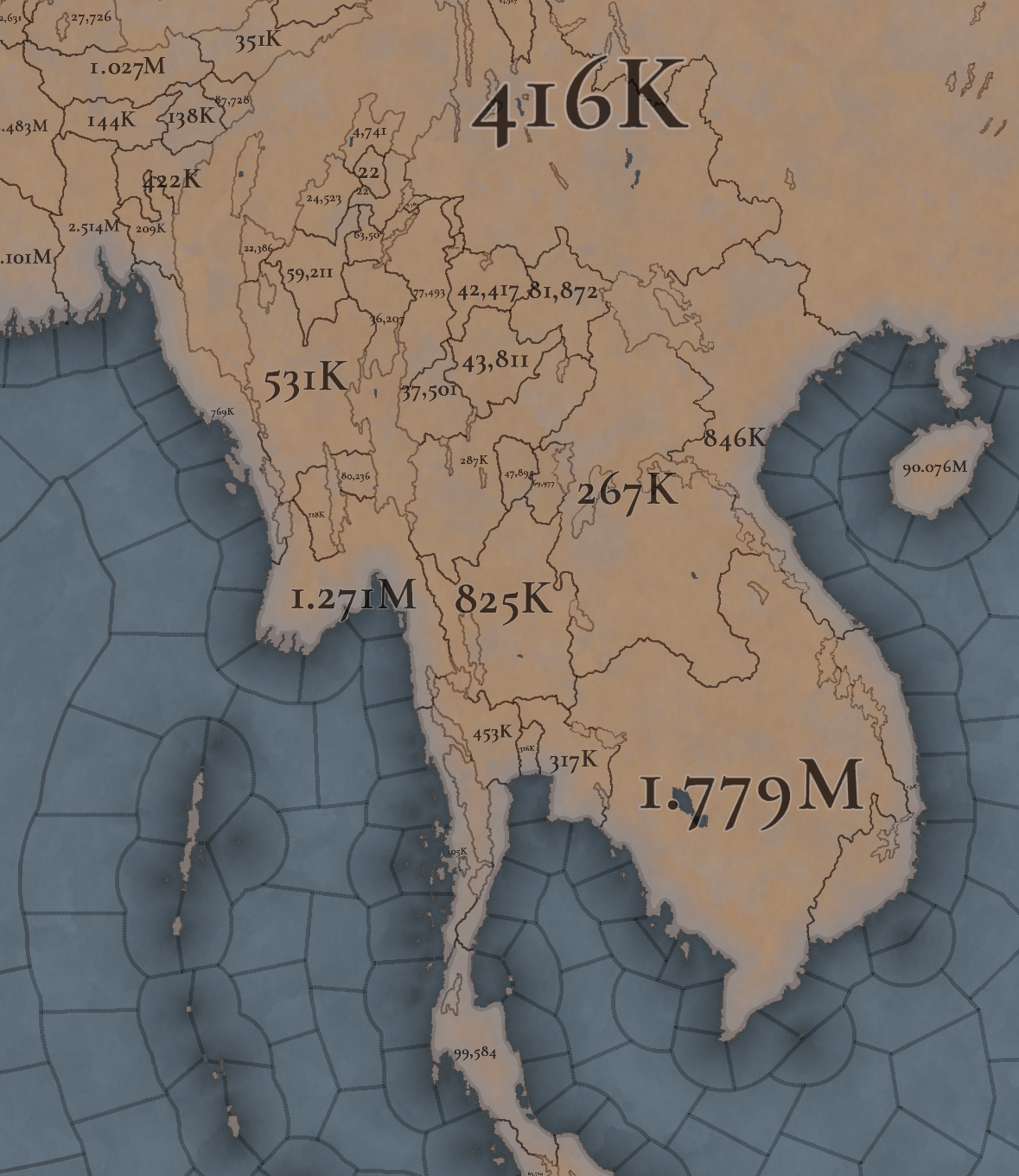

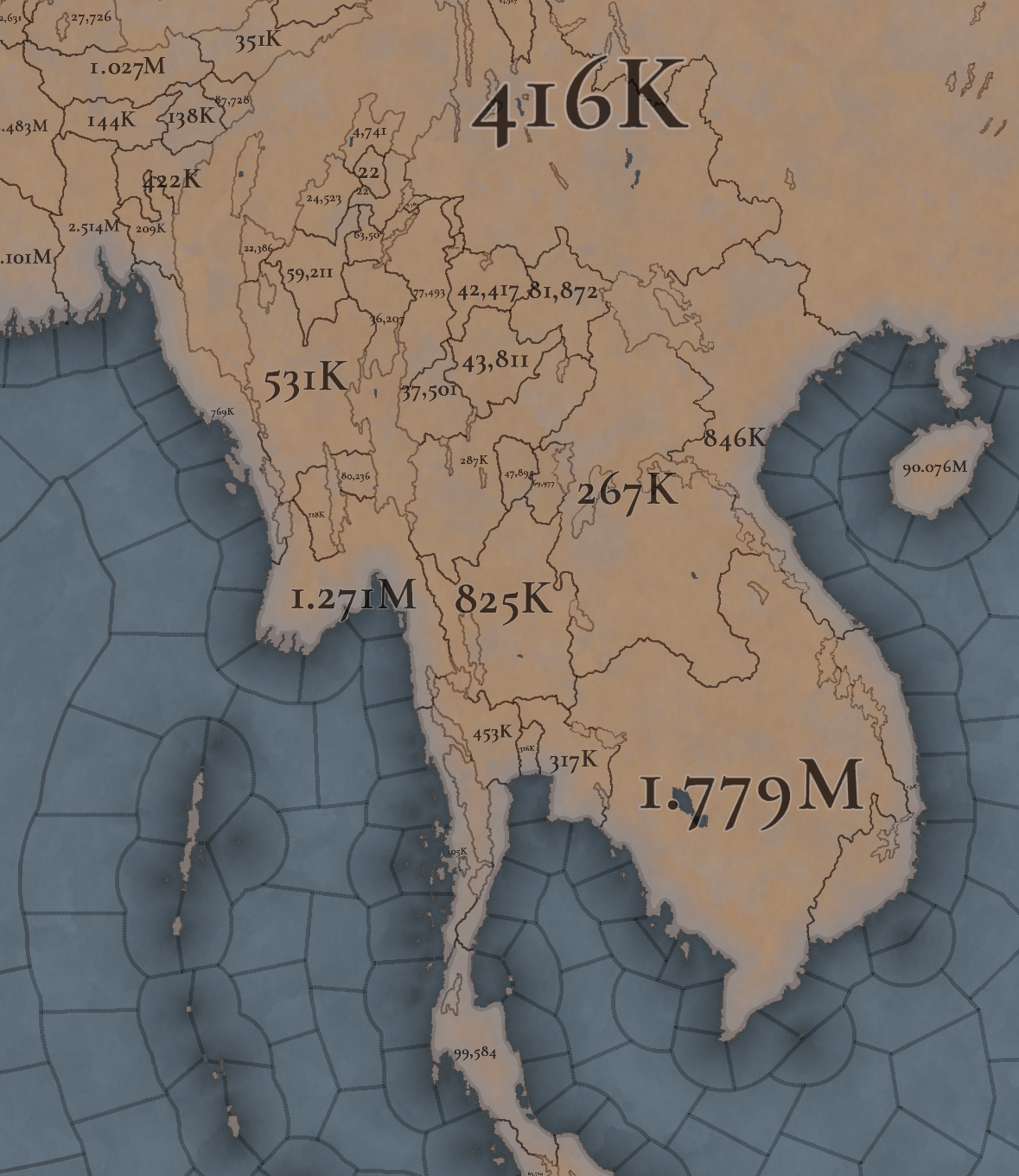

Population

Khmer is still the most populated, but other countries around don’t fall that far behind, especially when they manage to unify their areas a bit. There’s also a couple of locations appearing as 0 population that is definitely a bug that will have to be fixed.

Khmer is still the most populated, but other countries around don’t fall that far behind, especially when they manage to unify their areas a bit. There’s also a couple of locations appearing as 0 population that is definitely a bug that will have to be fixed.

That is all for this week. Join us next week when we set sail to take a look at the maritime part of South East Asia by taking a look at all the archipelago of Indonesia (including the Philippines). Hope to see you there.

Countries

Quite a variety of countries in the area. The regional power in the decades before 1337 was the Khmer Empire, although at this point they are already in decline and have lost much of their previous hegemony. On the west, the fall of the Burmese Pagan Kingdom and the following Mongol invasions gave rise to the disunited kingdoms of Pinya, Sagaing, Prome, and Toungoo, while in the south the Mon kingdom of Hanthawaddy (also known as Pegu) also split apart. On the center, the decline of the old Lavo Kingdom and its subjugation to the Khmer gave way to the emergence of the Kingdom of Sukhothai when Khmer started its decline too, and Sukhothai is emerging as the dominant Thai kingdom in the area. However, Ayodhya is already gestating the rise of another great kingdom, as King Ramathibodi, the founder of the Ayutthaya Kingdom is already poised to gain power in the region. On the east coast, the Kingdom of Đại Việt is under the orbit of the Yuán, with constant conflict with the southern Hindu kingdom of Champa.

Societies of Pops

A region very rich in Societies of Pops, which will make it definitely an interesting area.

Dynasties

The dynasty of the old Pagan Empire is still alive in Prome, with many other dynasties in the region having ties with it, while the different Thai dynasties also have ties among each other.

Locations

Provinces

Areas

Unfortunately, currently the name of the sea area encroaches too much into the land (this will be fixed, don’t worry), but the blue area that gets underneath that name is Chao Phraya.

Terrain

Tropical and jungle almost everywhere, with quite a bit of comparison between the southern flatlands and the northern mountainous areas.

Development

Not as developed as the surrounding India or China, but the main centers of power (like Angkor, Pagan, and Sukhothai) are a bit more developed.

Natural Harbors

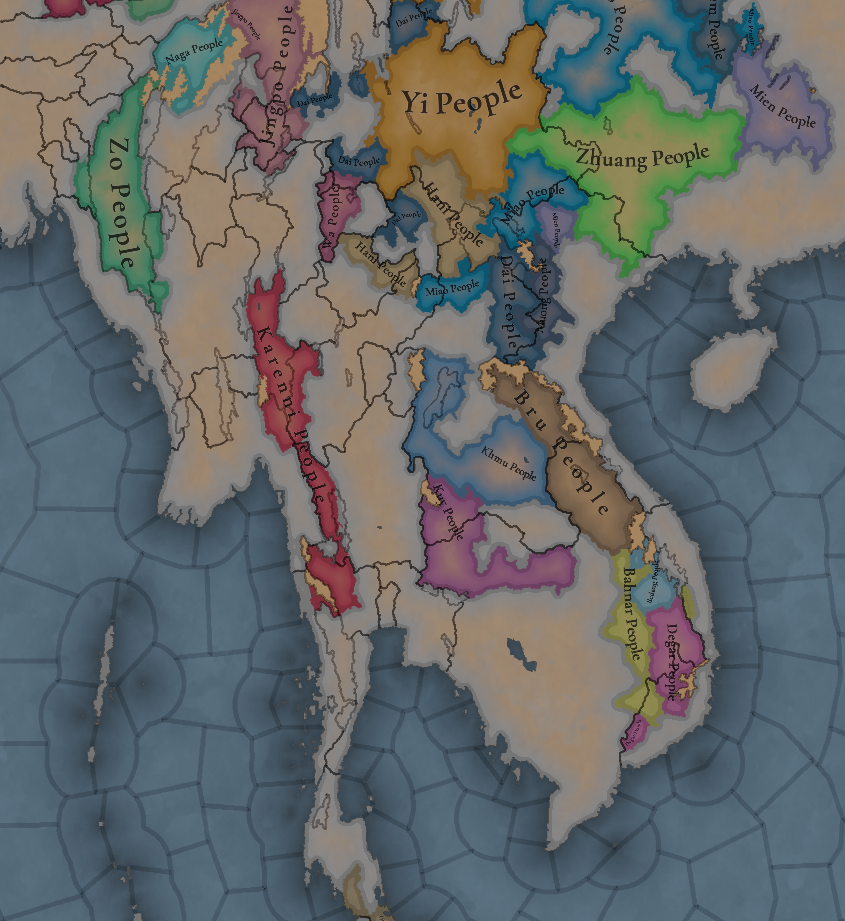

Cultures

A quite variety of cultures, although the southern areas haven’t had their minorities done yet so there will be even more variation there.

Languages

As an addition from this week one, we have a new map to show with the languages. Keep in mind that this area hasn't had any language families or dialects done yet, so there is a bit of grouping.

Religions

Again, keep in mind that minorities are not done, so there will be more variation added inside the Theravada block, as there has to be still quite a bit of Hinduism presence in Khmer (its conversion from Hinduism to Buddhism at that point was one of the causes of its decline), and quite a bit more of Satsana Phi among all the Tai peoples.

Raw Materials

Markets

The commerce is dominated by those countries benefiting from sea trade routes, but the emergence of a strong Ayutthaya Kingdom in the middle will for sure cause a change in the balance of powers.

Population

That is all for this week. Join us next week when we set sail to take a look at the maritime part of South East Asia by taking a look at all the archipelago of Indonesia (including the Philippines). Hope to see you there.