Lincoln was at home, sprawled on the floor with his boys, wrestling with them and with a decision whose consequences could change his life forever. Outside the windows a light dusting of snow had fallen; unusual for October but not so peculiar as to excite much comment in Springfield, Illinois, in the fallof 1859. The fireplaces and coal stoves were busily pouring out warmth, for while Lincoln was not exactly wealthy his legal career had prospered these past years and he was comfortably well-to-do, certainly rich enough that his family could afford a bit of extra coal.

On the tiny desk in the corner lay a letter, unanswered. Like its predecessor it offered Lincoln a speaking engagement in Brooklyn, in March of 1860, as one of a series of speeches by prominent Republicans. The lecture series had been organized by opponents of William H Seward, the prominent former Senator from and Governor of New York who was the presumed Republican nominee for the Presidency in 1860. Francis Preston Blair would lead off, Cassius Marcellus Clay would speak. Large crowds were expected, and for that reason the fee was comfortably large. Lincoln had no quarrel with Seward – the two men had only casual knowledge of each other – but the chance to speak on a national stage in the nation’s largest city was something he had wanted for many years.

Lincoln had dithered, leaving the first letter unanswered, but this one had come, phrased even more strongly. Clearly the organizers of the event wanted Lincoln… but did Lincoln want them? Public speaking had never appealed to him, but the prospect of speaking in Henry Ward Beecher’s church undoubtedly was attractive. Beecher was one of the country’s most prominent abolitionists, a powerful speaker and deep thinker as well as leader of a congregation of influential New Yorkers. His sister, Harriet Beecher Denton, had written the hugely popular anti-slavery novel ‘Life Among the Lowly’, also known as ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ for the setting of the first chapter. For this setting and audience Lincoln would have to prepare something very different from his usual stump speech, different even from the material he had used in the debates with Douglas. This would have to be closely reasoned, thoroughly grounded, meticulously prepared… and deeply moving. To have a chance at playing a part on the national scene he needed the national reputation that a great speech, delivered before a New York audience and covered by the New York newspapers, could give. If he went to New York he could make that reputation – but only if the speech was vigorously applauded, and this when his competition would be numbered among the greatest men the Republican Party had yet produced.

Over the next week Lincoln exchanged telegrams with his allies in New York. They responded that they hoped he would accept the invitation. He asked what they would recommend he say. The response was simple: he should address slavery and outline the Republican – the Lincoln – position on the institution; as to specifics they were confident he needed no guidance. Certainly this must have eased his fears that he was being manipulated or used as a figurehead. After the turn of the year into 1860, Lincoln at last accepted the offer, pinning down the date to Monday night, February 27th of 1860, giving Lincoln the last speech of the series. With his course set, Lincoln sat down to prepare for the speech the way he would have prepared for an important legal case, by thorough and meticulous research. He devoured every scrap of information he could find in reference to what the Founding Fathers had said, and done, and how they had voted on issues such as the Northwest Ordinance.

At last he boarded an Illinois Central train and departed for Chicago, the first stop on his journey to New York. At that city he found a private rail car had been assigned to his use, once the property of William Morrison and now set aside for his heirs. In quiet comfort he traveled the water-level route across Ohio and western New York, past the booming cities of Cleveland, Buffalo and Rochester. At Albany the rails turned south and ran along the bluffs above the Hudson River, descending at last to the mighty port of New York at the river’s mouth. There he found his rooms reserved by an alliance of the New York Telegraph and the organizers of the lecture series.

A wedding at the church had forced a last minute change of venue to the larger Great Hall of Peter Cooper’s Union School. A tinkerer, a self-made millionaire and the builder of the first American steam locomotive, Cooper intended his school to provide a free education for every student. The Great Hall was newly completed, and was one of the largest and best facilities in the city. Despite the snowy streets the hall was packed by over 1500 attendees, including prominent people such as William Cullen Bryant of the Evening Post, Horace Greeley of the Telegraph, George Putnam the publisher, Harris Denton and his wife Harriet Beecher Denton. At last the frontier lawyer was introduced by Bryant and took his place at the lectern. Here, at long last, was the opportunity of the lifetime, the full attention of the eyes and ears of New York, and by extension the United States and the world.

He did not begin well. His movements were stiff and awkward, his voice oddly high-pitched and querulous. But as the minutes went by and he warmed to the work, his hands ceased to clench and his voice deepened to a mellow tenor. His audience was carried along by his reasoning, as - in moderate, temperate but not conciliatory language - he laid out in his first section the Republican core beliefs, showing that a clear majority of the Founding Fathers had opposed slavery or supported the limitation of it. In the second part he addressed a few words to the Southern people, and in clear, concise and candid prose turned the most common talking points of the Southern Democrats back upon themselves.

“But you say you are conservative - eminently conservative - while we are revolutionary, destructive, or something of the sort. What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried? We stick to, contend for, the identical old policy on the point in controversy which was adopted by ‘our fathers who framed the Government under which we live;’ while you with one accord reject, and scout, and spit upon that old policy, and insist upon substituting something new. True, you disagree among yourselves as to what that substitute shall be. You are divided on new propositions and plans, but you are unanimous in rejecting and denouncing the old policy of the fathers. Some of you are for reviving the foreign slave trade; some for a Congressional Slave-Code for the Territories; some for Congress forbidding the Territories to prohibit Slavery within their limits; some for maintaining Slavery in the Territories through the judiciary; some for the ‘gur-reat pur-rinciple’ that ‘if one man would enslave another, no third man should object,’ fantastically called ‘Popular Sovereignty;’ but never a man among you is in favor of federal prohibition of slavery in federal territories, according to the practice of ‘our fathers who framed the Government under which we live.’ Not one of all your various plans can show a precedent or an advocate in the century within which our Government originated. Consider, then, whether your claim of conservatism for yourselves, and your charge or destructiveness against us, are based on the most clear and stable foundations.”

In the third part he addressed his remarks to Republicans, advising them on the formidable task of confronting and communicating with the men of the South:

“…what will convince them? This, and this only: cease to call slavery wrong, and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly - done in acts as well as in words. Silence will not be tolerated - we must place ourselves avowedly with them. Senator Douglas' new sedition law must be enacted and enforced, suppressing all declarations that slavery is wrong, whether made in politics, in presses, in pulpits, or in private. We must arrest and return their fugitive slaves with greedy pleasure. We must pull down our Free State constitutions. The whole atmosphere must be disinfected from all taint of opposition to slavery, before they will cease to believe that all their troubles proceed from us.”

His conclusion:

“Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the Government nor of dungeons to ourselves. LET US HAVE FAITH THAT RIGHT MAKES MIGHT, AND IN THAT FAITH, LET US, TO THE END, DARE TO DO OUR DUTY AS WE UNDERSTAND IT.”

With one accord the audience rose to their feet and, with applause and stamping and shouts of approval let the Illinois lawyer know he had succeeded perfectly in his aim; to the jury of these New Yorkers he had made his case. Moderate in language as opposed to Seward’s ‘irrepressible conflict’, legalistic in argument and powerful in emotional effect, Lincoln’s simple, short speech would vault him overnight onto the short list of Republican leaders of national stature.

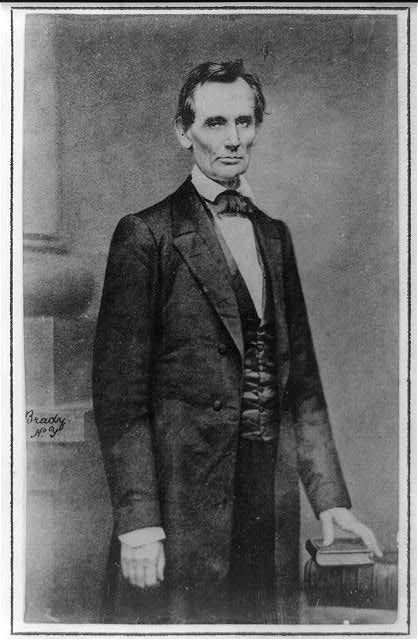

After the thunderous reception of his speech at Cooper Union, offers of additional engagements poured in and Lincoln embarked upon a whirlwind tour of a dozen cities in as many days. The speech was widely reprinted, usually coupled with this formal photograph taken by Matthew Brady. With this Northern exposure, Lincoln’s reputation was firmly established and his name was circulated as a prospective candidate for the Presidency.