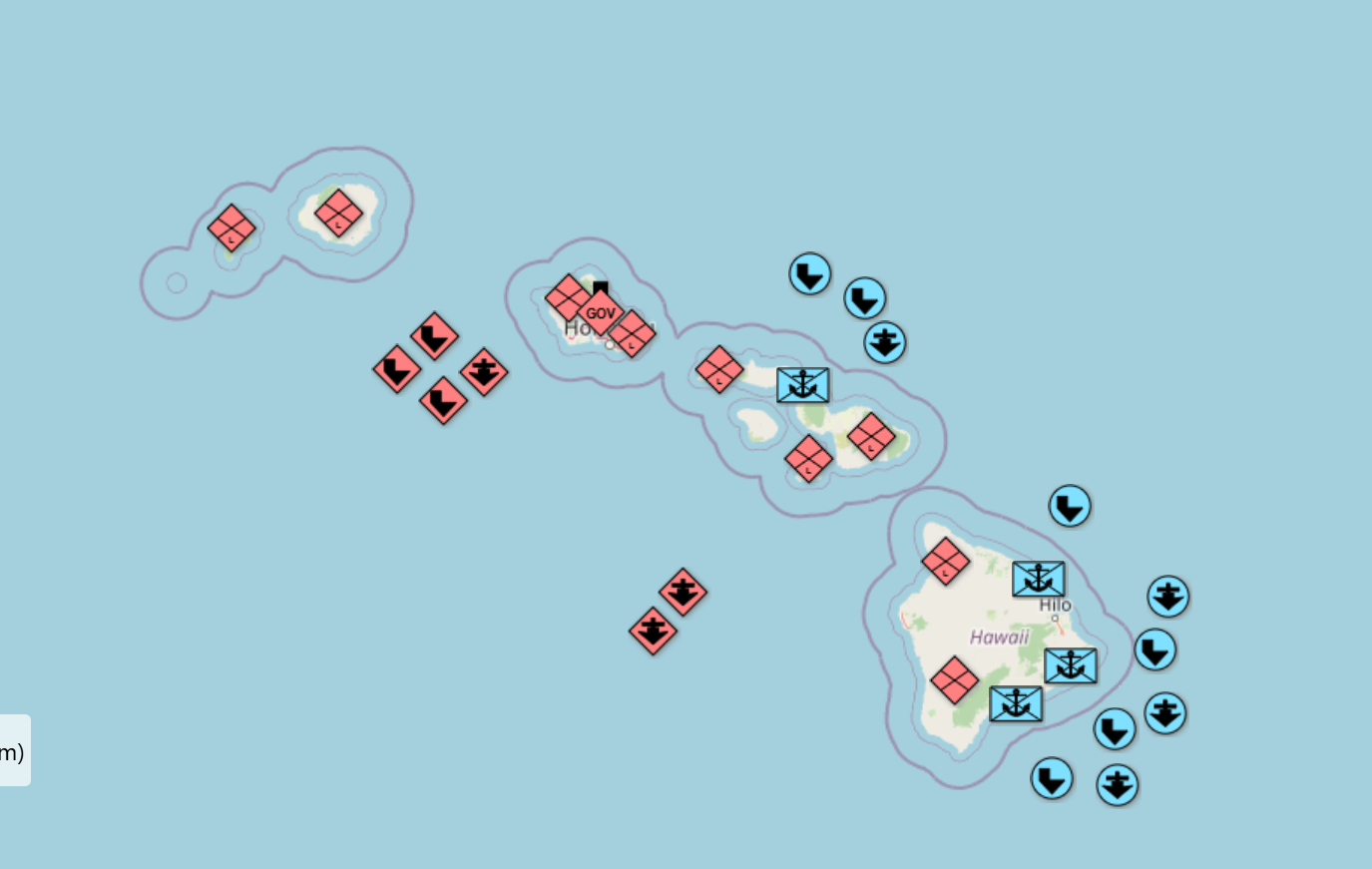

Despite the impressive scale of industrial mobilization, doctrinal overhaul, and the apparent institutional recovery of the Army, Navy, and Air Corps, it must be emphasized that, at the onset of the Pacific campaign, the United States remained a deeply fractured nation. The American Civil War of the 1936 had left not only hundreds of thousands dead, but also a society traumatized and politically unstable. While MacArthur had managed to re-establish a semblance of national order through a careful mix of militarization, seudodemocracy, and targeted propaganda, the reality was that this order rested more on forced discipline, the apatthy of the population and economic militarism than on genuine consensus.

The rearmament and professionalization of the armed forces were not solely strategic initiatives, they also functioned as an escape valve. The foreign war became a tool for national unification, or at least a temporary diversion from unresolved internal tensions. Official discourse spoke of reconstruction, redemption, and the reclaiming of global leadership; yet behind closed doors, many within the military and political elite understood that the war effort was, in part, a desperate forward march. MacArthur, despite his public resolve, knew that failure in the Pacific would not only entail territorial loss—it could unravel the fragile political structure he had painstakingly rebuilt since 1939. If Washington loses this war, all this Authoritarian Democracy would colapse.