Chapter 43: The Men in La Mancha (1132-38)

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

The Holy War for Slavonia and the Krain Raid

In February 1132, Sturla’s opportunistic grab for Slavonia (started against the Byzantine Revolt in October 1130) was well progressed

[warscore 78%] as the main army camped in Bononia to siege it down. By April the Revolt was hanging in against Basileus Alexandros II

[55% in the Empire’s favour] as Sturla tried to close out his campaign first. The fall of another holding on 3 April brought an end closer, but the Revolt refused to yield.

This changed on 1 June 1132, as Viseslav was taken while Byzantine armies circled but did not attack the Russians in Bononia. The peace was enforced on Eupraxia of the Byzantine Revolt and the inconvenient slice of Slavonian land was absorbed. And the Fylkir had earned himself an excellent new nickname for this victory done in the Gods’ names. While undoing all the hard work of recent years to reduce his threat perception.

The raid in Krain (Venice’s last county) continued while the third army was in central Italy – and would no longer need to attack Revolt land there to end the war. Varazdin was allocated to King Arni of Germany and Krizevci to the Marshal, Jarl Sverker II ‘the Effeminate’ of Yatvingia – both powerful Council members.

The levies were disbanded and the remaining Retinue and Jomsviking troops in Bononia and Italy invoked the Sacred Raiding Toggle, then began marching for Hispania. There, raiding riches beckoned and Russian magnates were involved in wars of expansion, which Sturla would also assist with where he could.

The raiders in Krain took another four holdings and 277 gold through to November 1132 and they too started marching for Hispania. These and the future raids in Hispania ended up taking a great many prisoners, with many a ransom paid over these years. The longest serving prisoners with no hope of ransom were gradually released, but there were usually 30-40 in the dungeon at any one time.

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

Court and Domestic Issues: 1132-35

The new Barony of Étempes in Paris was completed on time and under budget in March 1132. For now, despite the hit on vassal opinion and tax revenues, Sturla hung onto the castle, but did not seek to spend money improving it.

A betrothal was made for Crown Prince Olafr (then just two) to the infant Svanhildr Þorgilsdottir, daughter of the Jarl of Bjarmia – a distant Rurikid relation of Olafr’s and already showing signs of being very quick-witted.

In June 1132 the Seer Godi Ingjald of Tikhvin caught rabies, becoming incapacitated and dying the following month, replaced by the young Gydja Rögnfrið of Jamborg – not the most learned cleric but absolutely loyal, who would help shift the numbers on the Council in Sturla’s favour.

Empress Gyla was confirmed pregnant in January 1133 and in August gave birth to her first children – twin daughters, Elin and Guðrun.

In mid-May 1134, the growing treasury was able to sustain another major expansion of the Imperial Retinue. Eight new regiments were raised in Holmgarðr: three cavalry, two shock and one each of defence, housecarls and skirmish. In total, this would eventually provide another 150 heavy cavalry, 600 light cavalry, 250 pikemen, 350 archers and 650 heavy infantry.

Seeress Rögnfrið indeed proved to be

extremely loyal to the lusty Fylkir: the unmarried Gydja dropped a few hints and very quickly, an affair had begun. And it would prove to be more than a passing fancy.

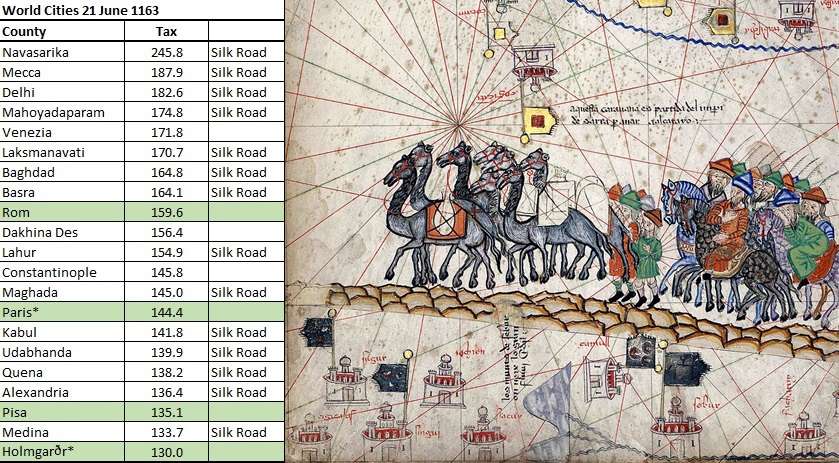

Among many conversions to Reformed Germanicism during these years, the best of all was Rome itself: once the seat of Catholicism, it saw Odin’s light on 5 April 1135. A thunderstorm in the city that day was said to be the sound and sight of the Gods celebrating.

By that time, Pope Urbanus II was 14 years dead, his 48-year reign marked by abject failure, madness in defeat and the near extinction of Catholicism. His successor Callistus II had died in 1133, with Benedictus VI now reigning the ‘Empty Papacy’ from the Roman catacombs. He would soon be succeeded by the young Pope Martinus II in January 1136 (aged only 36 at the time of his election).

The relatively new Imperial demesne county of Pest was flourishing by that month and a few weeks later embraced Norse culture. This was broadly positive, but now effectively wasted the money that had been spent earlier on the hussar training ground there. Still, it was progress.

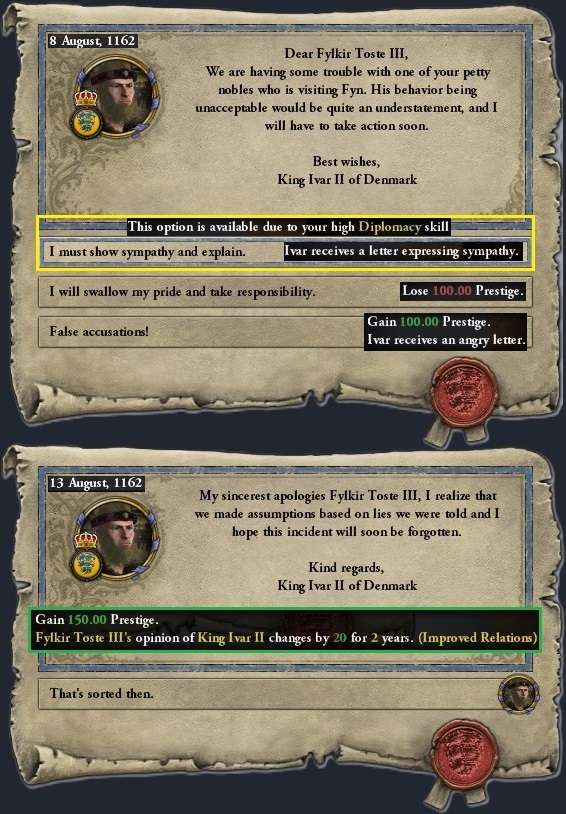

Sturla’s personal development was not neglected either: from July to November 1135, he apparently had an epiphany and emerged a renowned poet – and improved diplomat.

Foreign and Magnates Wars, Successions and Politics: 1132-35

King Arni of Germany had launched a

de jure war for Leiningen against Duke Engelbert of Franconia in October 1131. It took just over a year for him to win the war and eliminate another small ex-clave inside the Empire’s borders.

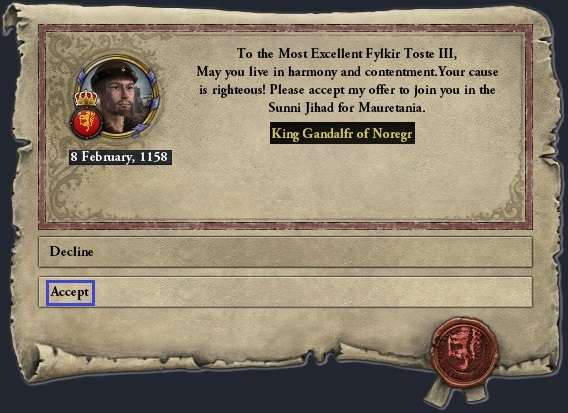

In December, King Hroðulfr of Volga Bulgaria launched a claim war for the crown of Noregr against young King Gandalfr. This war would still be in progress five years later, as was Denmark’s existing war to make Noregr a tributary.

Not unusually for even the best Spymasters, the incumbent Freyr was murdered by a rival in January 1133. This presented an opportunity to promote King Hroðulfr to the Council in an appointment he was well suited to.

Far from being disaffected presence in the Council, as many had predicted, Sturla's kinsman was well disposed after the appointment and would prove to be a pragmatist in Council matters. Which was good, because at this time Sturla was attempting to pass a new tax law to help boost revenue and he needed all the help he could get.

In mid-1133, King Refr of Sardinia and Corsica was defending in two wars – and the one against King Faste of Lotharingia and his ally Jarl Rikulfr of Savoy for Trier had turned from a likely victory for Refr to almost evenly balanced. At least Refr’s separate defence against Dauphine over Vermandois had ended inconclusively a few weeks before when the claimant died. But a new revolt war on behalf of one of his vassals, Jarl Toke II, had just broken out. Refr was under pressure.

By the end of 1133, the tax vote was still unresolved. Sturla approached King Hroðulfr and offered a favour in return for his support in Council for the next three years. Three weeks later, the law was passed.

King Refr recognised his hold on isolated Trier was unsustainable and conceded it to King Faste in mid-September 1134.

But Faste had less than two weeks to gloat: Sturla’s maimed personal enemy had been bitten by a rabid dog and by 27 September he was dead. Sturla could only chortle happily when he heard the news: how appropriate!

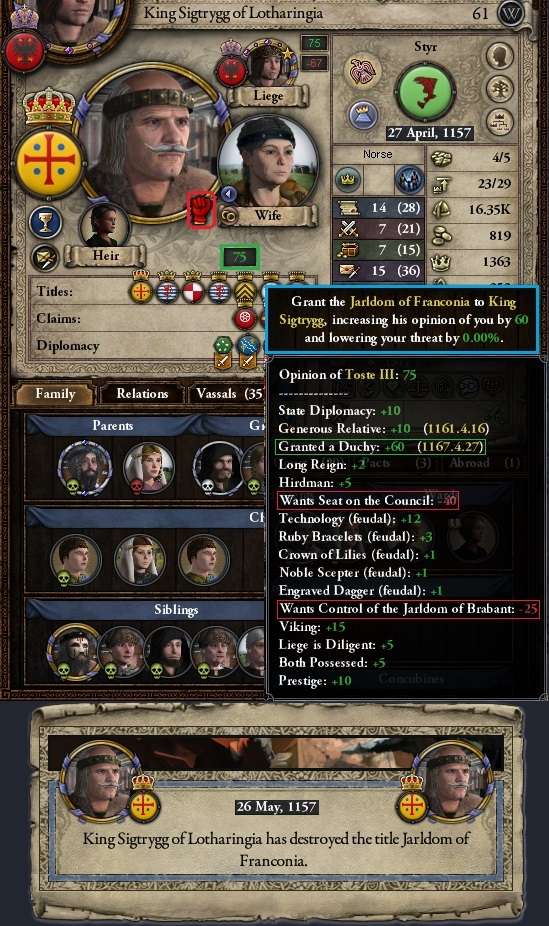

His replacement broke the long line of Yngling dominance over Lotharingia, stretching back to 1067. With elective monarchy now the succession law there, King Tyke of House Styr was elected to replace him. He did not like his Emperor much but at least he continued the recent Lotharingian tradition of mask-wearing kings.

Basileus Alexandros eventually won his civil war in October 1134 – but this would not be the end of his troubles in this period of Byzantine instability, as we shall see later.

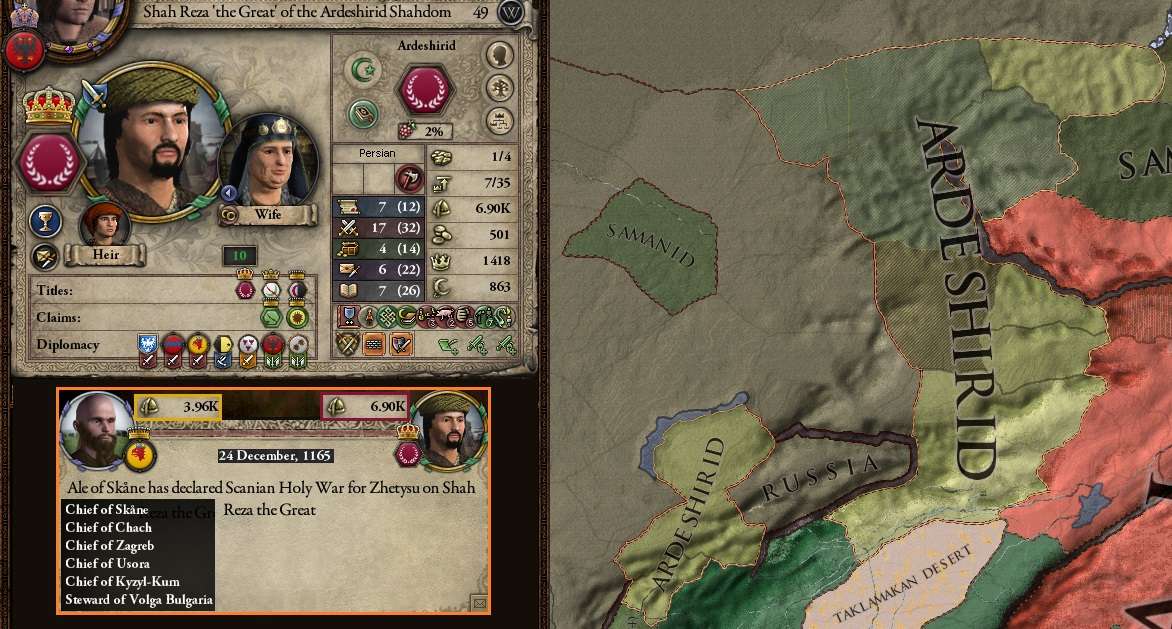

The Samanids remained one of the worlds great powers, despite being divided by civil war in February 1135. But such was the strength and ambition of the great Russian Viking lords of this time that Jarl Federigo of Susa (based in northern Italy), one of King Refr’s vassals, was able to muster a large invading host to declare an invasion of Persia.

Though Federigo’s reach and ability to project enough power that far away was of course questioned by many at the time.

The aftermath of the latest Byzantine civil war had seen the Doux of Athens – who held lands in Italy and the Balkans – assert his independence for Constantinople. Unfortunately for him, this meant he provided a tempting target for the most powerful of Sturla’s vassals.

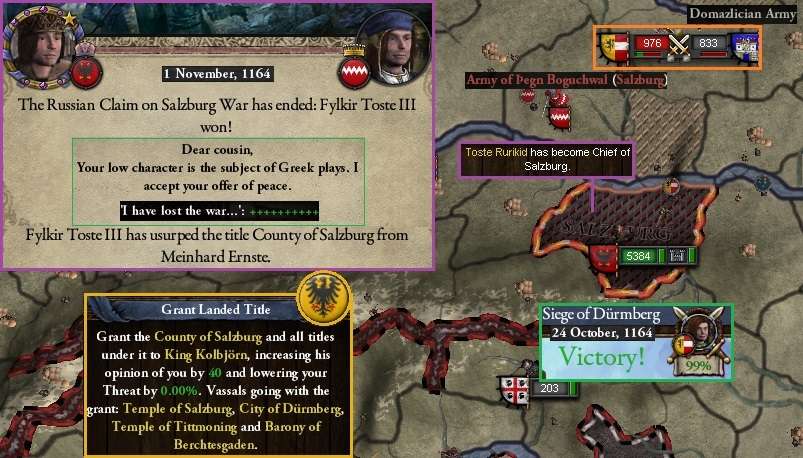

The young Doux found himself in big trouble as 1135 drew to a close. King Kolbjörn had extensive lands in Italy and used these as a base to launch a conquest of Foggia.

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

Hispanian Campaigns and Raids: 1132-35

In June 1132, the Almeríid Emirate in southern Hispania was beset by two Russian invaders. Jarl Rikulfr II of Savoy (supported by Lotharingia, Irland and Sviþjod) was well advanced in his conquest of Granada started in October 1127

[+69%]. King Bagge ‘the Holy’ of Bohemia’s ambitious prepared invasion of Andalusia (begun in July 1130) was still in its earlier stages

[+15%], while his target had the support of the Umayyad Emirate.

It was these conflicts – and the rich lands around Cadiz – that had drawn Sturla’s ‘professional’ armies to southern Hispania. The first to arrive was a force of 8,900 men under General Buðli which arrived in Granada in early May 1133. Duke Rikulfr of Savoy had completely occupied the county, but a peasant revolt had broken out. The Russians struck and defeated the 3,400 peasants for fewer than 80 men lost.

By 22 May they had resumed their march to Seville, where they aimed to begin raiding for loot, arriving there the next month. Meanwhile, the Bohemian army was to the south reducing in Umayyad Malaga.

It seemed the defeat of the peasants in Granada had also allowed Jarl Rikulfr to complete his conquest. This new outpost would open up more nearby rich lands to some very lucrative raiding.

11 June 1133 saw the first Russian raid commence in Seville – and Sturla’s men would still be marauding southern Hispania more than four years later. As the raid of Seville progressed routinely for the rest of the year, the other two Russian armies had been heading west, combining in Tarragona before marching to join their comrades, initially holding in Granada on 31 December 1133.

A few weeks into the new year, they would be on the march to Almeria, where an Almeríid -led force (now including the Calatayuds as allies) was trying to undo King Bagge’s earlier work. By this stage, Bagge’s invasion was still making little progress in net terms.

Jarl Rikulfr II (also a skilled Russian commander) led a large force of Sturla’s elite troops, while the Bohemians had joined Buðli in Seville. In one of the major battles of the period, Rikulfr attacked the enemy coalition on 2 March, eventually being joined by the Bohemians just as the pursuit was ending.

Although it was a crushing victory, one of Sturla’s commanders was killed as he got out ahead of his troops during the pursuit, being ambushed and slain. A siege of Almeria began – this time in support of Bohemia’s war effort rather than for plunder.

The castle of Almeria fell on 16 August, with Pochina and Baza assaulted and taken within the next week, fully occupying the county. Meanwhile, Buðli’s raiders had finished in Seville and moved on to start looting Aracena on 2 September. Rikulfr did the same in Umayyad Almansa on the 15th.

The Bohemians meanwhile won a battle in Malaga against the enemy’s main allied army in October and then a skirmish in Seville in November to keep their effort progressing. By the end of January 1135, Bagge was making good progress, with his Emperor’s assistance

[+38%].

Buðli was back in Seville on 1 June 1135, this time assisting the Bohemians to reduce the rest of its six holdings, of which they had taken one so far. Five assaults from then until the 27th saw few Russian casualties and the remaining five holdings taken, fully occupying Seville for Bohemia

[+76%].

The next move was to follow the Bohemians to Algericas, where they were once more taking on the enemy coalition off their own bat. Buðli arrived on 13 July but for reasons unknown did not join the fight, which Mayor Milic had well in hand anyway. The battle was won and the new round of sieges begun on the 31st.

Two Bohemian-led assaults followed and by 15 August two holdings were in Bagge’s pocket

[+91%]. Arriving in La Mancha for a new raid on 27 October, a new commander – General Odo – was in charge of the other raiding army. When a small enemy army slipped into Seville in November, Asa had assumed command and took her men north on 20 November to evict them before they could retake any of the lightly garrisoned holdings, leaving Mayor Milic to finish off in Algericas. That battle would be brief, with all 1,000 enemy troops wiped out from 2-11 December, for only nine Russian casualties.

During 1133-35, 16 holdings in Seville (Jun 1134-Jul 1135, 541 gold), Almeira (266 gold, Mar-Aug 1134) and Aracena (369 gold, Sep 1134-Jun 1135) yielded a total of 1,453 gold in sacked holdings alone, not counting miscellaneous raiding and ransoms.

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

Court and Domestic Issues: 1136-38

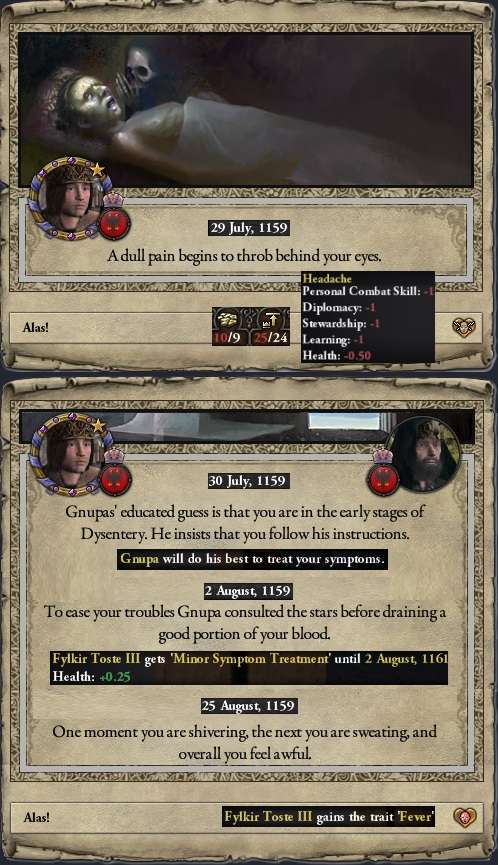

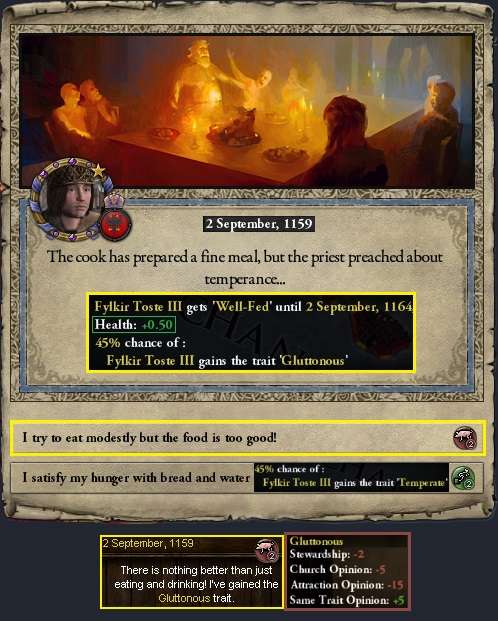

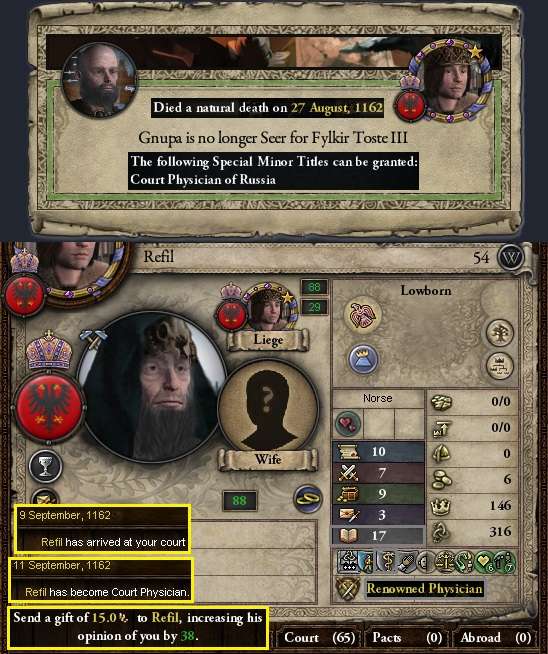

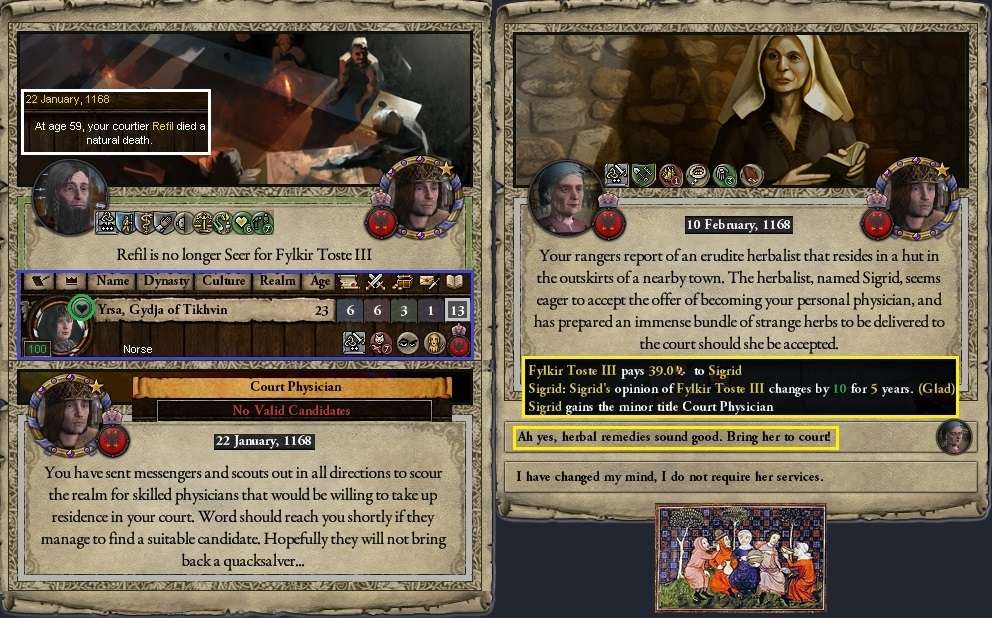

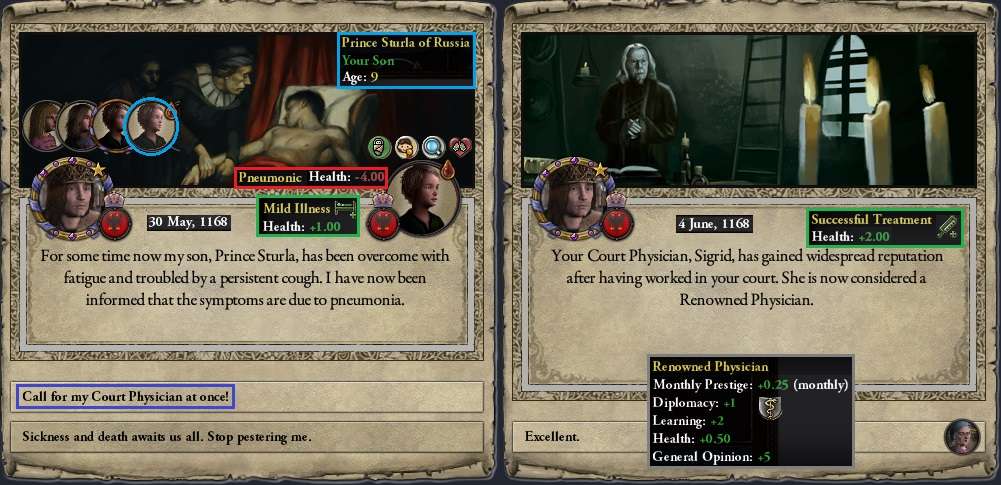

After a period where most news had been good for the Fylkir, at home and abroad, things took a grim turn in early 1136. Crown Prince Olafr was struck by a severe case of dysentery, which left the six-year-hold heir bedridden and in great danger. Court Physician Hrolfr was called in to assist – but his treatment proved ineffective and only seemed to worsen the situation.

Not wanting to be without a doctor at this time, Hrolfr was not imprisoned but did get a chastening tirade from the Fylkir. Then Sturla could only look on helplessly as his only son died just a few days later. The illness had proven swift and deadly. Once more, Sturla’s brother Prince Arni became the heir presumptive, as Sturla’s other three children were all girls.

The Emperor's response was swift: two of his older concubines were set aside, with younger women brought in (18 and 19 years old) – one of them sharing the Fylkir’s lustful desires. But the Emperor was also able to find some solace in the arms of his wife, Empress Gyla. Their love blossomed in the aftermath of the tragic loss of Sturla’s only son.

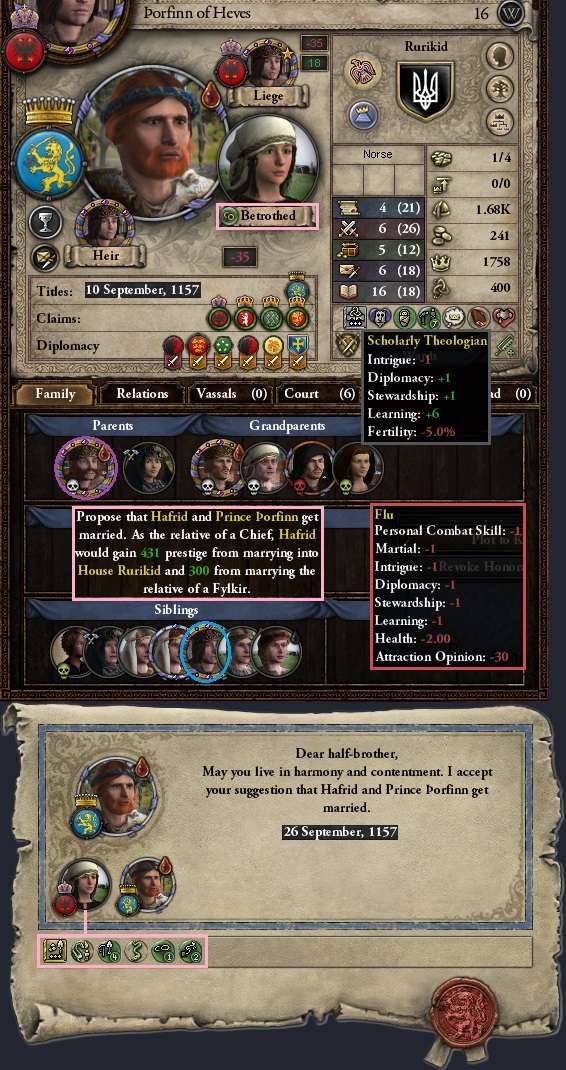

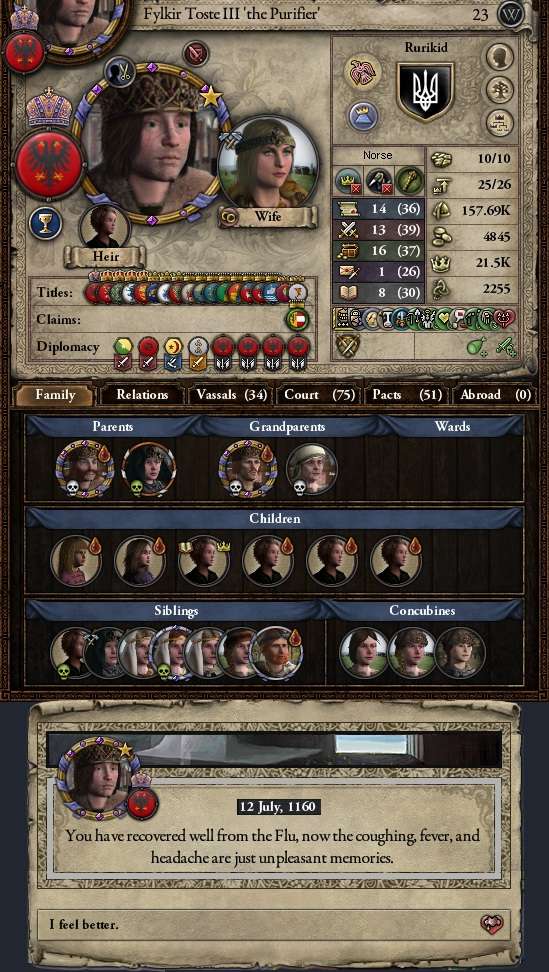

Then something came out of the blue to give Sturla an alternative option as heir: his lover, Seeress Rögnfrið, gave birth to a healthy boy on 14 September 1136. Sturla moved quickly to legitimise him but had to seek advice from the annals of Wiki the Red when the expected acknowledgement of him as the new heir did not come automatically.

Eventually, he was advised the problem was not legal but mysterious and spiritual. He must sleep under the stars for a night and commune with Odin himself. In his dreams that night, all was explained to him, though he could not remember the details when he awoke. But by 28 October, the new Crown Prince Toste was confirmed and acknowledged to all.

[NB: the wiki said you have to save, quit and reload to get this arrangement to ‘register’, for some reason. But it worked alright.]

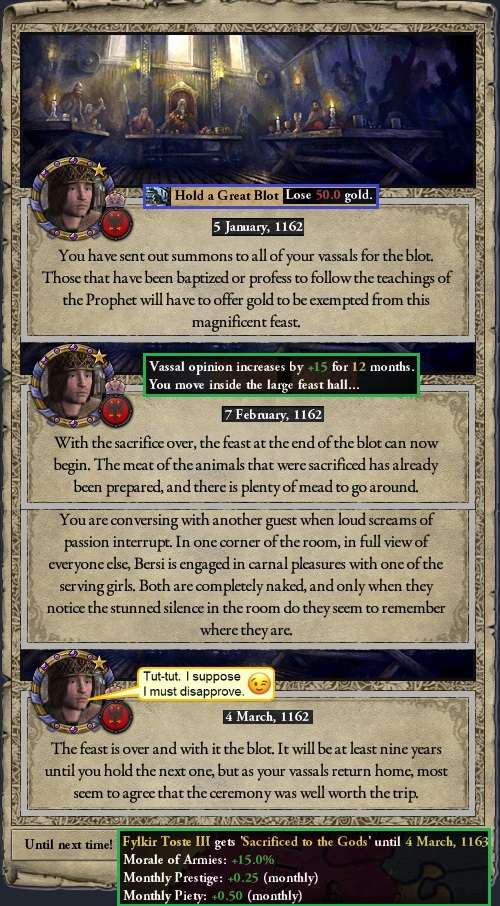

Sturla had happier thoughts on his mind as the year ended, however. 1136 was finished off with another Great Blot, setting up 1137 to be one of improved vassal opinion and significantly increased army morale.

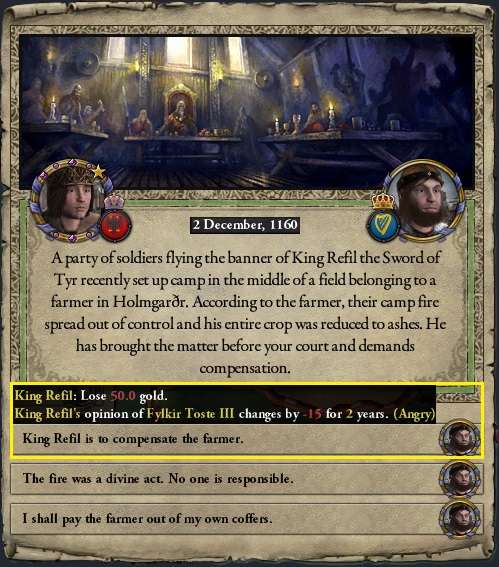

At home, Torzhok was now flourishing under Sturla’s rule, while King Hroðulfr used his favour with the Emperor to excuse himself for prosecution of a crime which could have seen him arrested but of which Sturla could not care less. The man was dishonourable and a known murder … but a kinsman and handy spymaster. Sturla shrugged and moved on.

Empress Gyla bore another child in September 1137 – a third daughter. Sturla had hoped for a ‘spare heir’, but it was not to be – yet, anyway.

At least his martial reputation and popularity were further boosted when all the raiding being done in his name earned him the title ‘Ravager’ soon afterwards.

In mid-December, the Baron of Okulovka (the third barony in Holmgarðr) died without an heir, the title reverting to Sturla (putting him now two over his demesne limit). He finally decided to award his brother (and still second in line to the throne) Arni a landed title, also giving him the ‘spare’ Barony of Étampes in Paris, removing another irritant to his vassals.

The new year brought another component kingdom into the

de jure Russian Empire after 100 years of Rurikid rule, Lapland no longer part of

de jure Scandinavia.

Building Works. As raiding loot flowed in and technology expanded within the Imperial demesne counties, new building projects were commissioned during periodically. From 1133-35, the more recently acquired counties of Heves and Pest saw military improvements made, though no more hussar training grounds would built, as Norse culture began to permeate Hungary as well. After Pest’s hussar training ground became redundant when it adopted Norse culture, a new housecarl training ground (282 gold) was commenced in November 1137 to replace it.

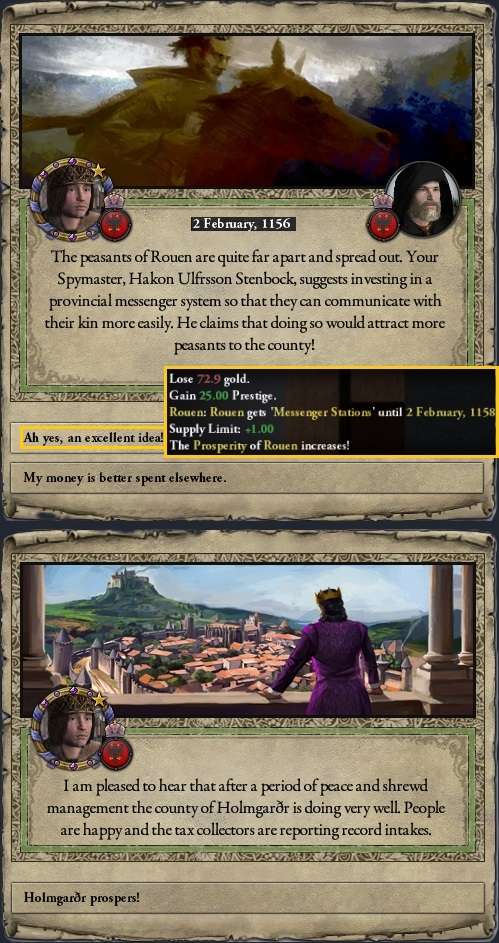

In 1136-7, it was improving medical technology that allowed the hospitals of Rouen and Toropets to have new sick houses built.

By 8 April 1137, the expanded sick house’s completion brought that county’s hospital to Level 3 (14% epidemics resistance), while that in Paris was already slightly more advanced (L3, 16% resistance). In Russia, the great Hospital of Holmgarðr was the most advanced in the Empire (L4, 35%), followed by Ladoga (L3, 29%), Torzhok (L3, 19%) and then Toropets (still at L2, 4%), where their sick house was yet to be completed, finished in December that year (to L3, 14%).

Religion. And the years since mid-1132 saw another 13 counties brought into Odin’s light, from Spain in the west to the eastern Steppe and Siberia.

Foreign and Magnates Wars, Successions and Politics: 1136-38

By October 1136, the long-serving Warchief and Russian commander Sörkver lost his position after a factional coup (the same way he had come to power himself 15 years before). But his successor was in for a turbulent time, with two revolts breaking out to challenge him in March (from the recently ousted Sörkver) and then another in June 1137.

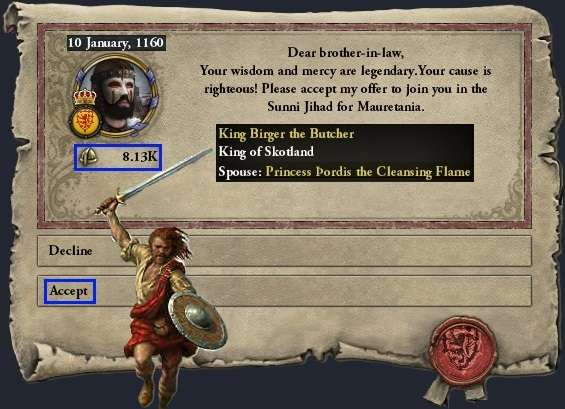

Germany managed to win a claim on East Anglia from Lotharingia in November 1136, after two and a half years of warfare, further expanding German influence in England and bringing them on a par with Lotharingia in terms of their military power.

In Byzantium, Basileus Alexandros' cruel nature must have led him into some excess, as from December 1136 he bore the epithet ‘the Evil’. And things would continue to get worse for him. By June 1137, the biggest revolt yet of his reign had broken out and this time the rebels significantly outnumbered him, controlling most of the Anatolian heartland.

While two more small breakaways had joined the Doux of Athens to become independent. For now, they were members of the anti-Russian defensive pact, but Sturla’s covetous Eye fell on them – and would stay there, looking for some opportunity to remove a little more border gore from the east of the Empire.

King Arni of Germany, as was becoming habitual in that part of the Empire, died soon after his recent victory, overcome by the stress of his responsibilities. As had happened in Lotharingia, the Yngling dynasty was ousted here as well, with a new king from House Hjort elected to succeed him on 20 June 1137.

The next major jarldom to suffer a bout of instability was Moldau. A long-running rebellion ended on 9 August 1137 with the Jarl Dyre deposed, replaced by the new Jarl Þordr. Who lasted just ten days before himself being deposed in a coup by one Sveinn of Cholet.

The chaos continued with a fresh revolt on 11 September to reinstall the usurper Þordr! It looked like Moldau would remain internally preoccupied for some tome to come yet.

Another second tier vassal helped fix an anomaly caused by a Norwegian inheritance of the old Rurikid and then Polotskian county back in 1073 by the then King Sigbjörn Ulfing of Norway on the death of his father, Guðmundr, who had been a Russian vassal of the Jarl of Polotsk. Sigbjörn taken Satakunda in Noregr when he became king, then had granted the county to Steinn av Hålgoland in 1119. His son Hrane had inherited the county as a child of two in 1124.

Two years later, King Sigbjörn’s had likely been murdered, with the current King Gandalfr taking the throne of Noregr. Then the current Jarl Sumarliði II of Polotsk, a Swedish vassal, had reclaimed it in the

de jure war just finished, leaving Hrane as chief but back under Polotskian, Swedish and Russian rule.

Another changing of the old guard occurred on 1 December 1137 when the favour granted King Hroðulfr II became moot: there was a new (and rather mediocre) ruler of Volga Bulgaria as his son too the reins of power in the east (and a range of other holdings in Europe, too).

As with his recent choice of Seer, Hroðulfr’s replacement as Imperial Spymaster Chief Ulfr of Charolais was not quite the sharpest stiletto in the rack but he too was very loyal. This reinforced Sturla’s growing control of the Council.

In late 1137 Sturla began a rather complicated (and perhaps far-fetched) plot to see if he could gain some kind of claim on the recently independent Syrt. The Count of Syrt had just the one daughter, who was his heir. The Orthodox noble would not willingly be vassalised – and arranging a ‘mixed religion’ non-matrilineal betrothal with his daughter may be difficult.

But it would be impossible to attempt while her current betrothed was alive. So a plot was hatched to get rid of this inconvenient suitor, to see what might then be possible.

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

Hispanian Campaigns and Raids: 1136-38

Asa’s smaller (just under 8,900 men) raiding army arrived to loot Umayyad Qurtubah on 7 April, fighting a ten-day battle against a smaller Umayyad force, with only ten Russian casualties lost while the enemy had 1,211 out of their 1,678 troops killed. Odo’s larger army continued to siege down the rich holdings of La Mancha.

Even as Asa fought the skirmish against the Umayyads, King Bagge wrapped up his campaign and in so doing seized the entire remaining Almeríid Emirate. He took direct control of Seville, Almeira and Algericas straight away.

Aracena was revoked from the defeated Suleyman ‘the Shadow’ a month later, but Mubashir of Niebla remained in charge of his county under Bohemian rule – for now. This major addition to the Empire also expanded the swathe of bordering counties Russia could now raid for loot. And propelled King Bagge well into the top tier of first-order Russian magnates.

Bagge soon made his move on Niebla in July 1136 but Mubashir refused the revocation and raised the flag of rebellion. It would take until June 1137 to overcome him and the county was revoked a month later, while Mubashir languished in Bagge’s dungeon.

The raiding continued through to early 1138. From 1136 to then, La Mancha (Oct 1135-May 1136, 316 gold), Qurtubah (Jan 1136-Jun 1137, 533 gold) and Badajoz (Aug 1136-Mar 1137, 304 gold) were all completely looted. New raids in Calatrava (from 31 Jul 1137, 91 gold) and Uhshununbah (from 20 Nov 1137, 98 gold) had already started to yield loot from the first holding sacked in each. Many more prisoners were also ransomed as Sturla’s dungeons overflowed with potential money-spinners. In these two years, 19 holdings had fallen for 1,756 more gold in pillaging alone flowing into Russia’s coffers.

ᚔ ᚱᚢᚱᛁᚲᛁᛞ ᚔ

Peasant Revolts: 1132-38

The usual sprinkling of revolts occurred during this time. The West Geatish uprising in Vestergautland was dealt with by a passing Danish army, ending in July 1132. Just a month later, a rebellion in Verona followed: this was very poor timing as Buðli was passing nearby at the time on the way to Hispania. The battles saw to rebellion snuffed out by 13 September (Russia 107/8,922; Rebels 2,153/3,642 killed).

In February 1133, a rebel force of 3,700 rose up in Zyriane on the Steppe but was defeated by October as local forces from Volga Bulgaria dealt with the scum without the need for Imperial intervention.

The next outbreak did not occur until April 1135, with Nizhny Novgorod the latest trouble spot. As nothing had been done by the local lords by the end of August, Empress Gyla was put in charge of a force of the new retinue plus a limited levy muster, consisting of about 7,400 troops to deal with the 3,300 rebels. But just before they would arrive in November, the Jarl of Ryazan had managed to muster his troops and defeat the rebels without the need for Gyla’s support. The levies were sent home and the retinue army (now around 2,000 strong) headed back to Holmgarðr.

Finally, in June 1137 2,300 peasant rose up in distant Ili, on the eastern Steppe on the Samanid border. With no local reaction by late October, Jarl Rikulfr II of Savoy was given command of the Holmgarðr-based retinue and began a long march to the east, just in case they would be needed.