Chapter 70 (1400 – 1410)

Władysław, son of Jakub V, was deeply shaken by the sudden death of his father. Only recently had Jakub been commanding the armies against Tamerlane, and now he lay motionless, like a stone, on the floor of his own tent. This shock was difficult for the new Mazovian monarch to bear. Yet Władysław quickly composed himself. The situation demanded swift action, and so he was crowned that very same day by the royal chaplain, Henryk Zamojski, in the presence of the Mazovian troops who had witnessed it. Only after the assembled nobles swore an oath of loyalty to him did Władysław begin to consider how to end the conflict and return to the Empire as quickly as possible, fearing that the great dukes of Mazovia might soon begin plotting against him.

The war with Tamerlane had dragged on for nearly eleven years and remained unresolved. According to the reports Władysław had at his disposal, the Timurid armies were currently near Edessa, numbering some 80,000–90,000 men. Jakub V had attempted to wage a guerrilla-style campaign after the disastrous Battle of Aleppo, where the Mazovian forces had suffered massive losses. Since then, he had avoided giving battle to Timur—who likewise avoided engagement. But the situation had changed. Władysław now needed to end the war quickly, as the authority of the imperial crown was at stake. He gathered his forces and marched toward Edessa, hoping for a decisive confrontation.

The Mazovian army, numbering 120,000 men—including mercenaries and reinforcements from the Continental Empire—was intended to crush Timur’s forces near Edessa and bring an end to the war. However, the battle never took place, as Timur withdrew eastward before the Mazovians arrived, halting near Harran, where he prepared for the encounter. Władysław remained cautious, suspecting that Tamerlane was trying to lure him into a trap—and he was right. Timur had indeed prepared an ambush: he occupied a hill that was ideal for repelling enemy attacks, and at its base, he had ordered the digging of wolf pits to thwart any cavalry charges.

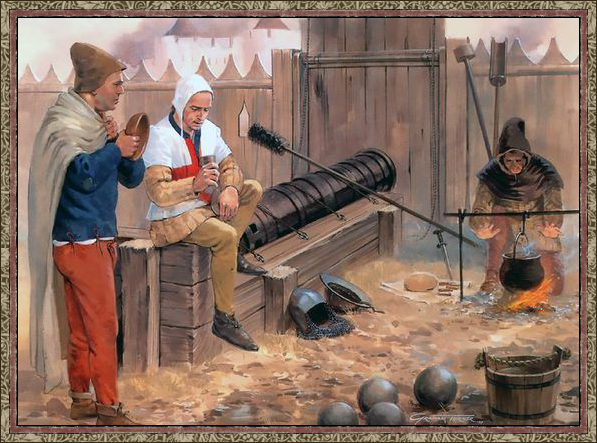

Upon arriving at the battlefield and surveying the terrain, Władysław realized that assaulting the hill would be difficult for his heavily armored cavalry. He was unaware of the pits at the base, but he had no intention of launching a frontal assault anyway. His father, Jakub V, had brought bombards from the Empire—primitive artillery weapons first used in Europe around 1379. Though Władysław knew they were of limited use in field battles and better suited for sieges, he planned to use them to exploit the fact that Timur’s army was tightly packed on the hill and unfamiliar with such weapons.

The chaos unleashed among Timur’s ranks after the first bombard shots was indescribable. His forces fell into a panic, trampling one another and even stumbling into the wolf pits. A flank attack on such a disoriented enemy seemed like a sound tactic. However, the ferocity of Timur’s troops took the Mazovian soldiers by surprise. The ensuing battle, triggered by a charge, lasted nearly the entire day and ended with Timur retreating toward Babylon. Yet this costly victory came at a high price: Władysław lost 40,000 men, and only about 65,000 remained fit for further fighting.

After the battle, which took place in December 1401, Tamerlane withdrew toward Babylon. In June 1402, peace was signed between the Empire and Timur. Timur acknowledged his defeat—he had little choice, as continuing the war was no longer viable. Additionally, he needed to return to suppress Zoroastrian revolts in Persia. The Mazovian envoys sent by Władysław were received with honor—unlike previous times, their heads were not sent back, as was Timur’s custom. He accepted the proposed terms of a "white peace," in which neither side gained nor lost territory. The war officially ended in April 1402. A few months later, Timur the Lame died, leaving his empire to be picked apart by vultures. The ensuing wars among his sons and the ongoing Persian Zoroastrian uprisings led to the collapse of the Timurid Empire within the next 20 years.

The great dukes of the Mazovian Empire, who had been beyond imperial oversight for nearly a decade, began plotting behind the backs of Jakub V and then Władysław III. They formed a faction comprising the most powerful Mazovian vassals, led by Duchess Beata Sublimowska of Prussia. While Władysław was engaged at the Battle of Harran, they sent a letter to Antioch with their demands: the imperial crown was to release them from feudal obligations and grant them full autonomy over their domains. These demands were unacceptable, as they signaled the disintegration of the Mazovian Empire. Władysław, unwilling to yield without a fight, refused Beata and all her noble supporters.

In response, the Prussian duchess and her allies launched an armed rebellion against Władysław. He had to return to the Empire as quickly as possible, for Poznań came under siege by the forces of Duke Zdzisław II Rogalski of Lusatia just a few weeks later. Władysław’s wife and children were in grave danger—Agata, their eldest son Ryszard, and two younger daughters could all be killed by the rebels. Władysław could not count on the support of the Moldavian Republic, as it had sided with Beata. Forced to return overland, the journey would take him at least two years. His march faced few obstacles. Władysław secured aid from Trebizond and Epirus; both Theocharistos and Constantine contributed 20,000 men each, giving him a force of 120,000 upon entering Moldavia.

The Mazovian army, led by Władysław, crossed the border in August 1405. The first target was the port city of Białogród on the Dniester, where he intended to punish the merchants for defying him. The siege proved problematic, as the merchants were resupplied by sea and Władysław could do little to stop it. Moreover, time was pressing—Poznań was well-fortified, but it was unclear how long its defenders could hold out. Władysław moved north, leaving 40,000 men to maintain the siege of Białogród. This proved to be a tragic error. His remaining force of 80,000 encountered the rebel princes’ army—150,000 strong—in Podolia.

The battle ended in defeat. Władysław was forced to retreat into Moldavia, only to discover that the merchants had bribed Marshal Jan of Rawa, whom he had left in charge of the siege. Władysław had nowhere left to go. He had lost his numerical advantage, and his men—exhausted from the long war with Timur—began deserting at night. The small town of Bilce, in central Moldavia, became the site of the final battle of the war and the final chapter in the history of the First Mazovian Empire.

In a last desperate move, Władysław decided to attack the traitor Jan before the rebel army could reach Bilce. If successful, he planned to retreat to Epirus, where he hoped to recruit mercenaries and anyone willing to fight for the promise of land. He managed to defeat Jan’s forces, but his remaining 65,000 troops were unable to withstand an assault from the rear. The rebels arrived sooner than expected. Their vanguard of 45,000 soldiers attacked Władysław’s rear, trapping his army. When Jan committed his reserves to the battle, Władysław was surrounded and doomed to a crushing defeat. Fighting for his life in the chaos of clashing steel, he suffered a mortal wound at the hands of a common infantryman. As he bled out on the muddy battlefield, his final thoughts were of his family—he knew their fate was sealed, and that pain was greater than any inflicted by his torn abdomen.

After the battle, the fate of Poznań was sealed. A few months later, the city fell, and Władysław’s family was murdered on the orders of Duke Zdzisław II Rogalski of Lusatia. The city was reduced to ruins—continuous barrages from catapults, trebuchets, and a few remaining bombards destroyed the buildings and monuments erected under the Piast and Zygmunt dynasties. The civilian population suffered terribly at the hands of Zdzisław’s troops, who looted, raped, and slaughtered with impunity, encouraged by their lord.

Zdzisław intended to proclaim himself the new ruler of Mazovia. The Empire had ceased to exist, but the Kingdom of Mazovia was there for the taking. However, he never succeeded. On April 20, 1409, Jerzy Czartoryski, Duke of Brandenburg and Silesia, attacked Zdzisław’s army camped outside Poznań. The Lusatian forces were routed and decimated. Zdzisław was captured by Jerzy, who personally executed him in the city square before the people of Poznań, who had suffered greatly under his cruelty. Jerzy Czartoryski then proclaimed himself King of Mazovia amidst the ruins of the Poznań Cathedral.

- 2