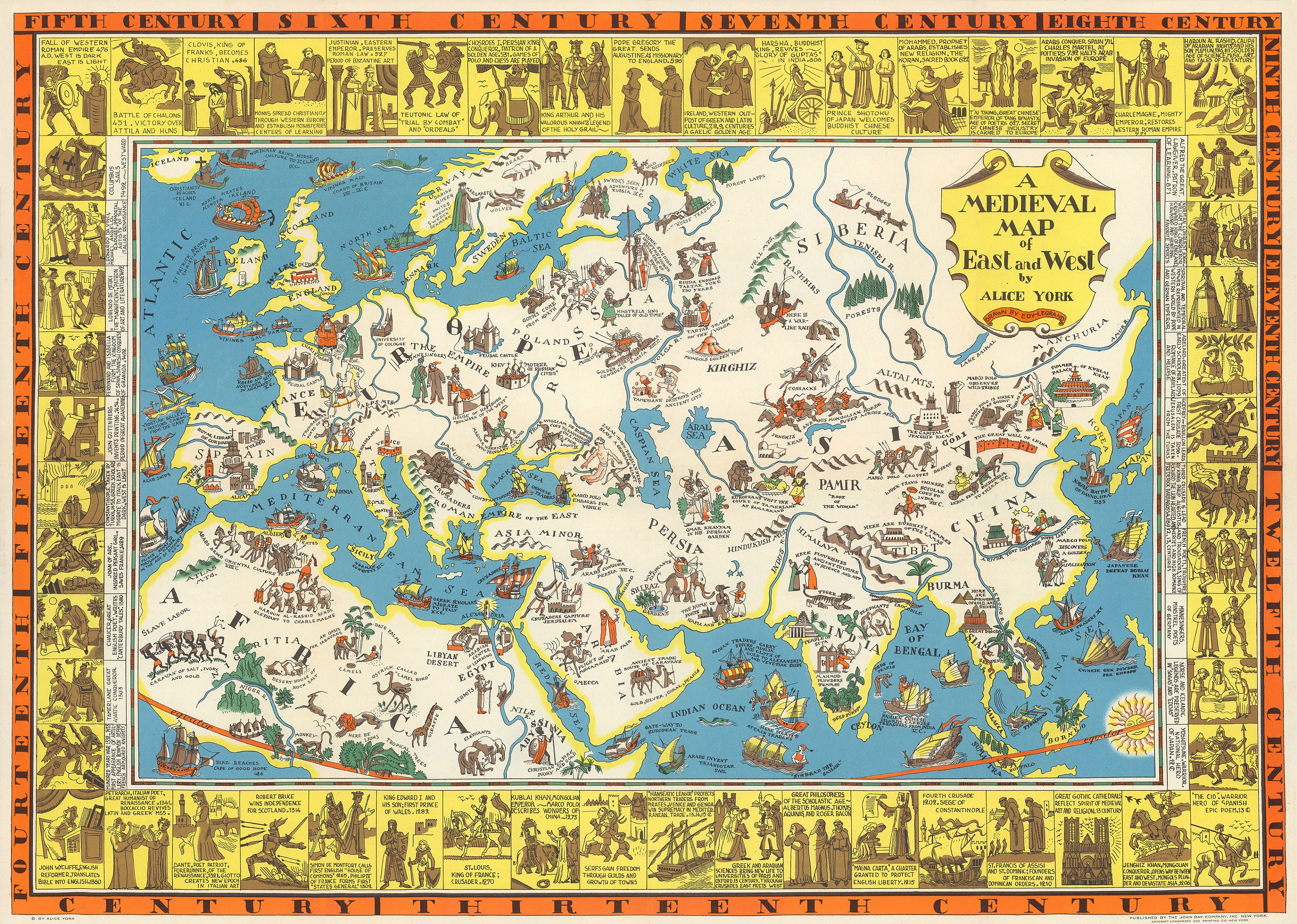

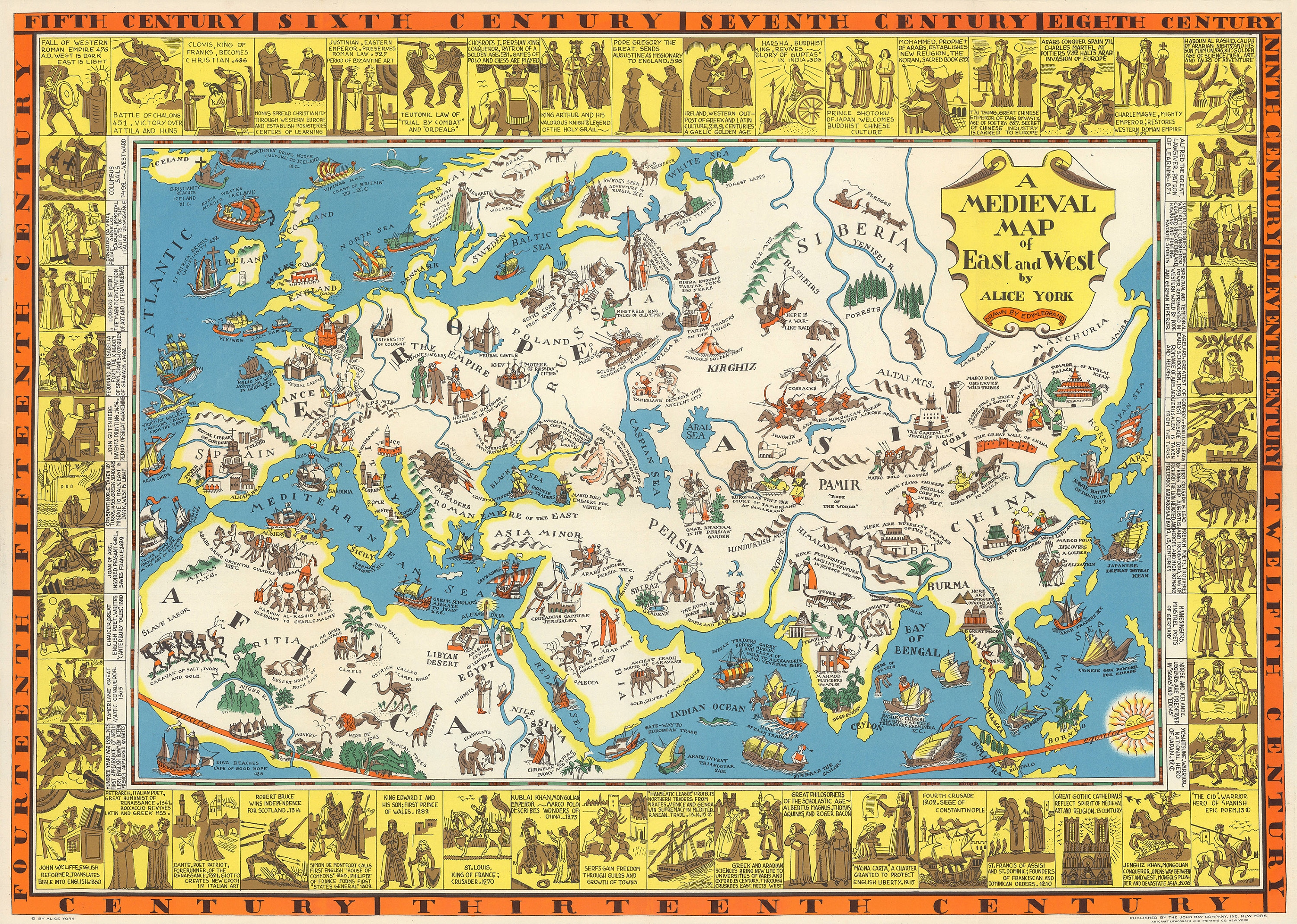

Western Europe in 1300

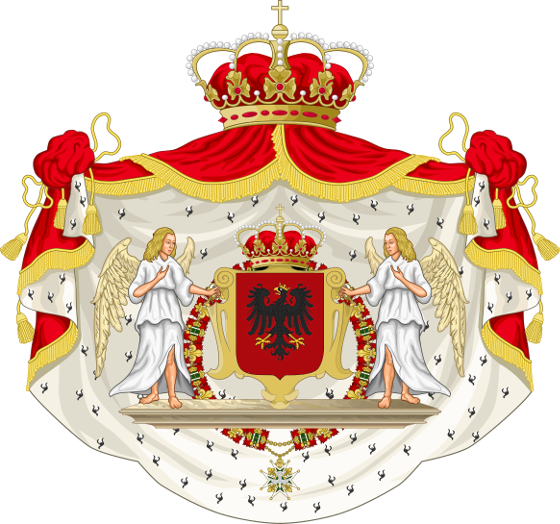

Królestwo Kastylii-Aragonii - Kingdom of Castile-Aragon

Królestwo Leonu - Kingdom of León

Królestwo Portugalii - Kingdom of Portugal

Królestwo Akwitanii - Kingdom of Aquitaine

Królestwo Francji - Kingdom of France

Królestwo Burgundii - Kingdom of Burgundy

Królestwo Bawarii - Kingdom of Bavaria

Królestwo Lombardii - Kingdom of Lomabardy

Królestwo Karyntii - Kingdom of Carinthia

Królestwo Sycylii - Kingdom of Sicily

Republika Sardynii-Korsyki - Republic of Sardinia-Corsica

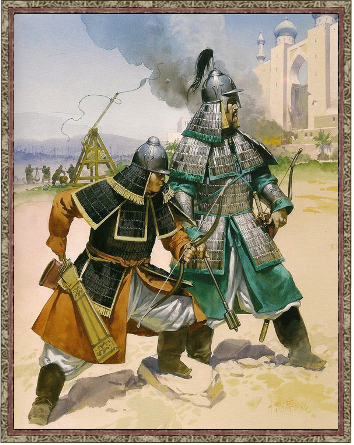

Kharedid Sułtanat - Kharedid Sultanate

Jdill Sułtanat - Jdill Sultanate

Aghlabid Sułtan - Aghlabid Sultanate

1 - Duchy of Galicia

2 - Kingdom of Brittany

3 - Kingdom of Lorraine

4 - Kingdom of Middle Lorraine

5 - Kingdom of Swabia

6 - Duchy of Brabant

7 - Duchy of Balaton

8 - Kingdom of Croatia

9 - Kingdom of Bosnia

10 - Kingdom of Serbia

11 - Papal States

12 - Rassid Sultan

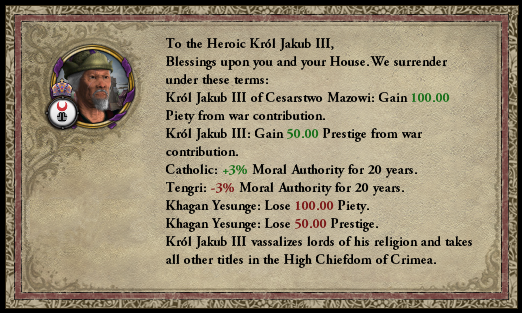

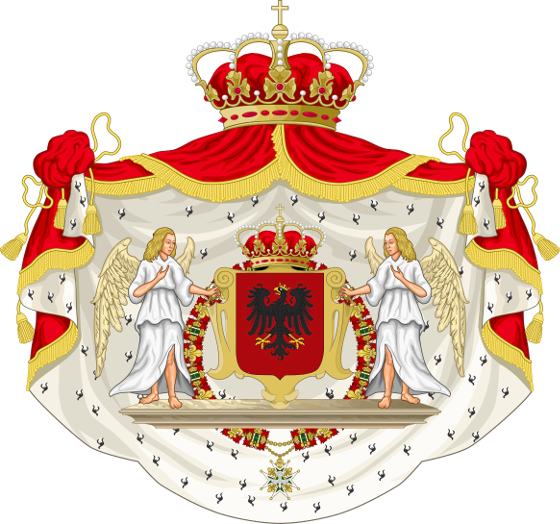

The Kingdom of Castile-Aragon traces its roots back to the Kingdom of Asturias, which emerged after the fall of the Visigothic state following the Muslim invasion. During the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in the early 8th century, the mountains of Asturias became a refuge for the Visigothic aristocracy.

After the Muslim victory in the decisive Battle of Guadalete in 711, where the Visigothic King Roderic fell, the Visigothic state was conquered. The Muslims, arriving from North Africa, occupied almost the entire Iberian Peninsula within a few years. In 722, under the leadership of Pelagius, Christian forces achieved their first victory at the Battle of Covadonga.

Pelagius then established the Kingdom of Asturias, marking the beginning of the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula. In 894, the Kingdom of Asturias transformed into the Kingdom of León, officially founded in 895 when the Christian rulers of Asturias moved their main stronghold from Oviedo to León.

By the year 1000, during the reign of Bermudo II the Brave, who also ruled Castile and Portugal at the time, León, along with the Kingdom of Navarre, had pushed the Muslim invaders out of the northern territories of the Iberian Peninsula. Dynastic divisions and unions on the Iberian Peninsula led to the unification of the Kingdom of Navarre and León in 1067. However, this union did not last long, as with the extinction of the House of Cantabria in 1123, the powerful kingdom fragmented into several smaller states.

The Iberian Crusade, organized in 1151 by Pope Sylvester IV, finally expelled the Muslims from Iberia, and their lands fell into the hands of the Knights Hospitaller. By 1200, the Castilian ruler had managed to reclaim the thrones of Navarre and Aragon. With the fall of the Hospitaller state in the Holy Land in 1280, the Castilians incorporated parts of the southern Iberian Peninsula into their domain, as did the Portuguese rulers. By 1300, the Kingdom of Castile-Aragon was the undisputed hegemon of the Iberian Peninsula, continuing its expansion across the Strait of Gibraltar into Morocco, which became the site of bloody conflicts between Christians and Muslim Berbers.

In 843, under the Treaty of Verdun, the Frankish Empire was divided into three parts. The western part, the West Frankish Kingdom, was taken by Charles the Bald and later by his successors from the Carolingian dynasty. The Carolingians, who ruled the West Frankish Kingdom and Aquitaine, eventually died out. Both kingdoms were ruled by the Carolingians almost until 1026, when the Carolingian line in the West Frankish Kingdom ended with the childless death of Burchard I.

The throne then passed to the Frankish noble dynasty of de Boulogne, who, after a victorious war against the Carolingians ruling Aquitaine, consolidated their power. In the following decades, the Kingdom of France, under the rule of the de Boulogne dynasty, sought to unify the lands of the Frankish Empire under its control. However, these attempts were unsuccessful, as successive wars ended in defeats, and the dynasty was overthrown following an Aquitanian invasion in 1157.

After 1157, the Kingdom of Franco-Aquitaine emerged, ruled by the de Lapen dynasty. This dynasty had taken power in Aquitaine after the death of the last Carolingian in 1108. From 1157 to 1189, the dynasty ruled the combined crowns of France and Aquitaine. In 1189, a rebellion broke out in France against the Aquitanian rulers, lasting until 1197. After the war, the de Lapen dynasty lost control of France, which gained independence and came under the rule of the new de Karel dynasty. Today, the Kingdom of France is a strong state, though surrounded by rivals who would gladly see its end.

In 843, the Treaty of Verdun divided the Carolingian Empire, and its Italian portion went to Lothair. The Kingdom of Lombardy emerged after the dissolution of the Kingdom of Lotharingia and the fall of the Carolingian dynasty in this part of Europe, which occurred between 945 and 952. As a result of this conflict, the powerful Kingdom of Lotharingia, which at its peak encompassed all of Germany and northern Italy, disintegrated.

The Kingdom of Lombardy was founded by Walter I Unorchiger, whose dynasty is one of the few to have maintained its rule to this day. Lombardy, between the years 1000 and 1300, struggled with its neighbors to the south and north. Wars with Burgundy and Bavaria mostly ended favorably for Lombardy.

Over time, Lombardy absorbed the Republic of Venice but lost control of these territories after the war with Bavaria from 1105 to 1116. Bavaria, however, did not hold these lands for long, as the independent Kingdom of Carinthia emerged there in 1158. After the establishment of the Kingdom of Sicily, the Apennine Peninsula was almost evenly divided between the two kingdoms, which fought a series of wars for dominance between 1200 and 1300, though neither side emerged victorious.

- 2

- 1