Chapter 56 (1315 - 1320)

Chapter 56 (1315 - 1320)

The years spent in military camps during the war of succession with Przemysław changed Jakub. Most notably, his relationship with food transformed. Once a glutton, he now grew accustomed to the modest meals prepared by his field cook, losing his compulsion to overeat and finding moderation.

The war with his brother and Lambert also revealed Jakub's tactical genius. In his childhood, Władysław had entrusted his firstborn son to his trusted marshal, Bezprym of Chełmno, a seasoned man of 58 years at the time. Bezprym had learned his craft during the reign of Jakub II, Jakub III's grandfather.

In his youth, he had served Jakub II's mother, Cathan, and fought against the rebellion of the Grand Duke of Halych-Volhynia, Władysław II Korecki. In later years, he participated in wars against Byzantium, the Kievan Rus, and the Golden Horde.

Bezprym passed on all the knowledge he had accumulated over years of warfare to Jakub, who absorbed it eagerly, like a sponge soaking up spilled milk. The armed conflict with his brother ensured that Jakub was no longer a novice in military matters. Everything Bezprym had taught him, combined with his own experience gained during the war, made him an outstanding strategist. The civil war of 1309-1314 awakened in Jakub previously hidden ambitions for his state and a desire to match the greatness of his namesake and grandfather, Jakub II. All these traits, developed during the previous conflict, proved invaluable now as Jakub faced the armies of Khan Ysunge of the Golden Horde.

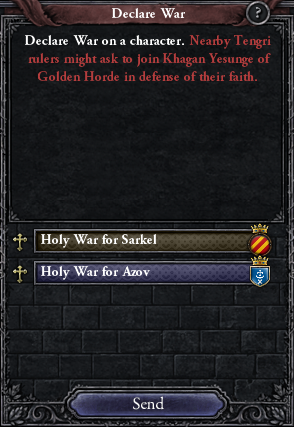

The civil war had weakened the Empire enough for Ysunge to dare attack, hoping for an easy victory. He likely believed that the Mazovian state, recently torn apart by fratricidal conflict, would be an easy target for his barbarian hordes. He did not realize that the Empire's coffers had swelled after Lambert's exile and the confiscation of his wealth by the crown.

Dorota had substantial gold reserves, which she used to hire mercenary banners. However, a problem arose as some mercenary leaders refused to sign contracts with Jakub, having heard of what happened at the Battle of Kalisz and unsure if the Mazovian Emperor would keep his word.

Those willing to take the risk demanded exorbitant payments. In the end, Jakub managed to hire around 15,000 soldiers ready to fight on his side. Despite his issues with church hierarchy, Jakub secured support from the Teutonic Order and the Knights Hospitaller, who provided an additional 10,000 troops. Combined with the mercenaries, these forces totaled 25,000 men. In Jakub's absence, Dorota gathered all available knights from his vassals, amassing another 10,000 men. Her efforts ultimately brought together an additional 35,000 soldiers, whose command she entrusted to Prince Radosław of Smolensk, the Imperial Marshal since Czcibor's death at the Battle of Kraków. These forces headed south three months after Jakub's departure from Poznań.

The news reaching Jakub about the Golden Horde's aggression was not encouraging. The Mongol forces had largely bypassed the border fortifications built over the past 30 years. Jakub II, Jakub III's grandfather, had begun constructing a series of border fortifications after the war with the Khanate in 1278-1280 to limit Mongol mobility in future conflicts. Ysunge's forces bypassed many castles, besieging only the most strategically significant ones.

In the first weeks of the invasion, they captured key crossings over the Dnieper. Reports indicated that the Mongol army was divided into two parts: one heading toward Kyiv and the other toward Halych. The exact size of the Mongol forces was unclear, but scouts estimated the army heading toward Halych at around 50,000-60,000 men. Jakub, with an army of 65,000, marched toward Halych, intending to intercept the Mongol forces and engage them before they reached the city.

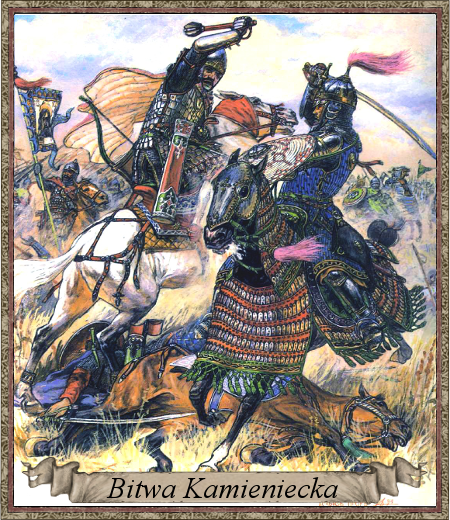

The Imperial forces encountered the Mongols near Kamianets. Jakub had meticulously planned the battle based on detailed information from his scouts and local nobles tasked with hindering the Mongol advance. He knew they were moving along the Imperial road toward Halych. It is worth noting that the Empire had a well-organized network of roads connecting its most important cities.

While only the Imperial domain had begun constructing stone roads resembling Roman ones, the rest of the Empire was covered with dirt roads. The Mongol commander's carelessness would lead to his defeat. Using the road gave Jakub an advantage, and he planned an ambush in a favorable location. He chose a spot where the road entered the dense forests of the Przemyśl region. Jakub's forces waited on both sides of the road, hidden in the underbrush.

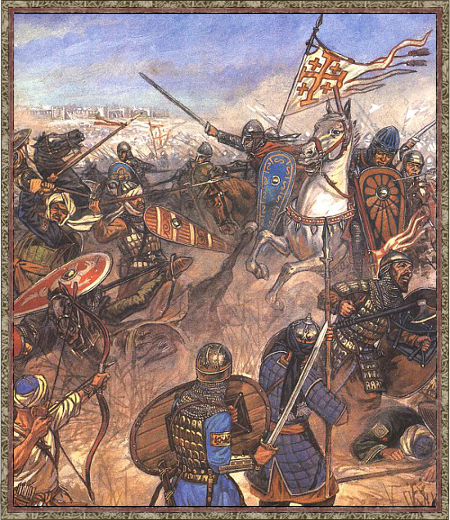

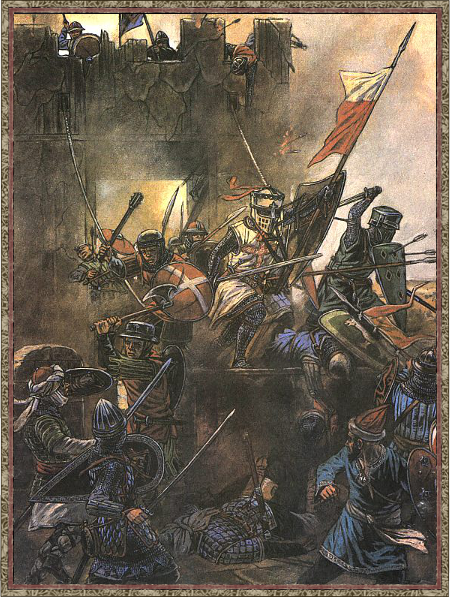

On April 11, 1316, at noon, the Mongol forces entered the forests of the Kamianets principality. The ambush was only partially successful, as the Mongol commander realized something was amiss and began withdrawing his troops. Jakub could not let the enemy escape. Knowing only part of the Golden Horde's army was in the forest, he ordered an attack. The fighting quickly spread from the forest to the surrounding areas.

The Mongol forces were disorganized in the initial phase and suffered heavy losses, but on open ground, they put up fierce resistance. The battle lasted until late afternoon and ended in a partial victory for Jakub. He inflicted significant losses on the enemy but also lost many brave knights. Worse, part of the Mongol forces managed to escape and head east toward Kyiv, which was under Mongol siege at the time. Kyiv's fortifications were incomplete, their construction halted by the civil war, so Jakub knew the city would likely fall to Ysunge. Mazovian losses amounted to around 15,000 dead, while the Mongols lost about 24,000. Several prominent Mongol commanders were captured and interrogated by Jakub.

Jakub personally participated in the interrogation of the captured Mongol commanders. Thanks to his mother, Gurbesu, a Mongol princess, he had learned the language well enough to communicate with them. Although the Mongols of the Golden Horde had a slightly different dialect from those of the Ilkhanate, it did not hinder understanding.

Jakub and one of his commanders inspected 15 prisoners of high enough rank to know something useful. Jakub selected two: one who seemed unbreakable and another who appeared terrified from the start. Jakub intended to use the sight of his companion's torture to loosen the second man's tongue. With his torturer, Jakub took both men to a nearby tent equipped with all the necessary tools. The other prisoners were placed nearby to hear their comrades' fate.

The interrogation began with Jakub asking simple questions about the location and size of the remaining Mongol forces. The defiant prisoner remained silent, while the fearful one seemed to draw strength from his companion's resistance. "Very well, cut off three fingers from this fool's right hand. Let's see if he sings after that," Jakub ordered. Bolesław, the torturer, obeyed. The screams were horrific, but the prisoner's spirit remained unbroken. Jakub repeated his questions, but the man remained silent. "Burn the stumps with hot iron. Let's see if that loosens his tongue," Jakub commanded. The Mongol's agonized cries caused his companion to convulse with fear. Jakub noticed the man had wet himself. It was the perfect moment to interrogate him. Jakub approached and asked the same questions. The man stammered incoherently, prompting Jakub to slap him and demand he stop stuttering or face a worse fate than his companion. The Mongol's eyes cleared, and he began to speak as clearly as he could.

From his confession, Jakub learned that Khan Ysunge himself was stationed near Kyiv with an army of 55,000 men. When they left the camp, the city was already under bombardment from ballistae and catapults. After extracting all possible information, Jakub ordered the other prisoners to confirm the details before executing them. While Jakub was in the torture tent, a messenger arrived from Marshal Radosław, informing him that reinforcements of 35,000 men were three days away. Jakub waited for their arrival and, after combining forces, marched toward Kyiv with an army of 85,000.

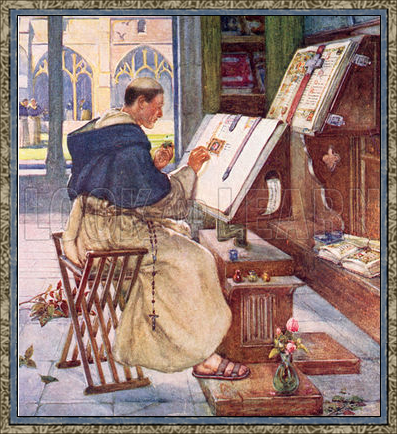

As Jakub headed south after the victory at Kamianets, a peasant uprising erupted in the Duchy of Poznań. Jaromił, the leader of the rebellion, was a religious fanatic driven by moral motives. He believed Jakub was a heretic and unfit to rule the Mazovian Empire. The uprising was inspired by Archbishop Bartosz of Mazovia, whose sermons encouraged disobedience toward Jakub and condemned his actions.

In his fiery speeches, Bartosz also slandered the monarch, calling him a sodomite and a heretic who fraternized with Jews. Many took these words to heart and decided to fight against Jakub. Unfortunately, only the lower classes joined the rebellion. After the war of succession, opposition to Jakub's rule among the nobility had vanished, and those who might have supported the peasants were imprisoned in Poznań Castle.

Thus, a 10,000-strong rabble set its sights on the Imperial capital, Poznań. Many of these men had never seen the city, and when they arrived at its walls, they realized they were outmatched. Dorota, residing in Poznań at the time, acted as she had during the siege of Vilnius. However, when she saw who was attempting to take the castle, she laughed and ordered her knights to make daily sorties to kill as many of these "foolish peasants," as she called them, as possible. She understood they had no chance of taking the fortress without siege engines, which they were incapable of building. The supplies in the castle would last at least three years, so she merely informed Jakub of the situation in Poznań.

Near Korsuń, Jakub's scouts spotted a rapidly moving Mongol army coming from Kyiv. Jakub deduced that the city had been captured and sacked, as Ysunge would not have abandoned the siege otherwise. Reports estimated the Mongol forces at around 75,000-80,000, suggesting the survivors of the Battle of Kamianets had joined the main army near Kyiv. This meant Ysunge wanted to engage Jakub before he could receive reinforcements. When Ysunge saw the Mazovian army waiting for him near Korsuń, he must have been deeply surprised, but this was irrelevant to Jakub, who intended to win here and end the conflict, allowing him to crush the peasant uprising.

Both armies took up positions opposite each other on November 15, 1318. Jakub planned a frontal charge followed by a feigned retreat of his left flank, which would then be reinforced by reserves, trapping the Mongol left flank. The plan seemed simple and effective. Jakub also kept 10,000 knights from the military orders in reserve to deal with any surprises.

The battle began the next morning. The two armies clashed in a fight that yielded no results for nearly an hour. When Jakub signaled the feigned retreat, the Mongol forces initially took the bait and gave chase. However, they suddenly turned and struck the center of the Mazovian line just as Jakub's reserves began their attack. The Mongol left flank found itself behind the Mazovian center, while their rear was attacked by Jakub's left flank and reserves. The Mongol left flank was trapped, as was the Mazovian center.

Jakub immediately sent the knights to reinforce the left flank and attack the Mongol center. When this happened, the Mongol center collapsed and began to flee. Ysunge, seeing the battle was lost, sounded the retreat. Jakub forbade pursuit and ordered the destruction of the trapped Mongol forces. The slaughter of the surrounded warriors took the rest of the day, which was exceptionally bloody and grueling. The battlefield counted around 45,000 Mongols and 39,000 Mazovian and allied knights dead.

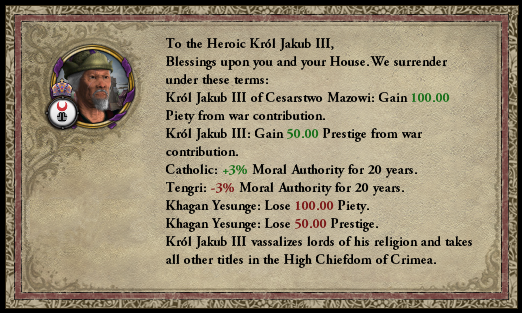

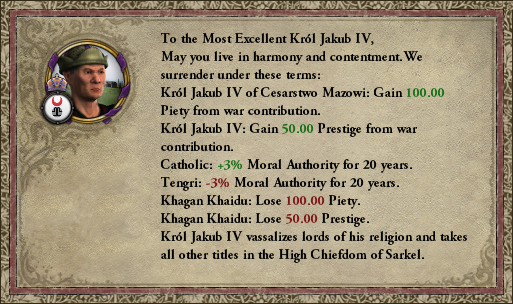

After the Battle of Korsuń, Jakub entrusted part of his forces to Marshal Radosław and marched with 25,000 men to crush the peasant uprising in Poznań. Radosław's campaign against the Mongols involved pursuing them to the Dnieper and the border between the two states, with frequent skirmishes between the Mongol rearguard and Radosław's forces. When Ysunge safely returned to his territory, he sent Jakub a peace proposal, offering a small war indemnity. Jakub accepted, vowing to settle accounts with Ysunge later.

Around July 12, 1319, Jakub's forces reached the outskirts of Kraków. He set up camp and sent scouts to assess the situation in Poznań. The reports indicated that the peasants had unsuccessfully tried to take Poznań Castle, which was too formidable for them. Jakub decided to rest his men before marching, as defeating the 10,000-strong peasant rabble should not be a problem. However, Archbishop Bartosz, who had long undermined Jakub's authority, remained a problem that needed to be resolved quickly to prevent further peasant unrest.

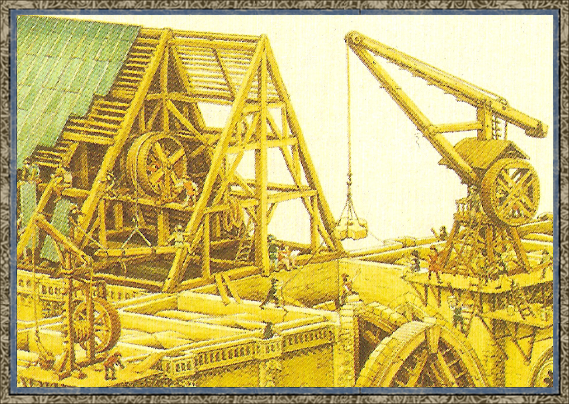

On July 20, Jakub's forces marched toward Poznań, where the peasant army was located. By early August, the Mazovian troops arrived. Jakub attacked the besieging peasants immediately. The battle at the foot of Poznań's walls was bloody, especially for the rebels, who were slaughtered without mercy. The clash lasted no more than two hours and ended in a complete Imperial victory. The rebellion's leaders, including Jaromił, were executed, while the remaining prisoners were sentenced to lifelong labor in the mines or on the galleys of the Lübeck or Gdańsk trade republics.

Crushing the uprising did not end Jakub's problems. The state was in poor economic condition. The civil war had devastated the northeastern and central regions, while the war with the Golden Horde had ravaged the southeast. To rebuild, Jakub would need the help of the Jewish population, whose trading and moneylending skills would be invaluable. However, such a move would lead to open conflict with Archbishop Bartosz, whom Jakub already considered an enemy and planned to remove in the near future.

- 2

- 1