@kakom : except for having succeeded in siring a male heir, Jakub I the Proud of Mazovia came across as a Mazovian version of Charles the Bold of Burgundy.

Any resemblance to historical figures is unintentional.

@kakom : except for having succeeded in siring a male heir, Jakub I the Proud of Mazovia came across as a Mazovian version of Charles the Bold of Burgundy.

Mazovia: Calls crusade on LivoniaCathan and Henryk agreed that the pagan Kingdom of Livonia should be eradicated due to its continuous raiding of Mazovian borderlands. To achieve this, they planned to request the Pope’s approval for a crusade against the Baltic pagans.

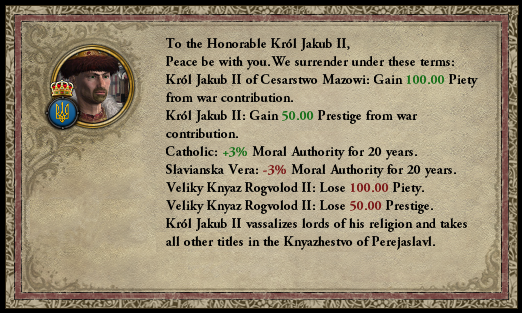

For over two centuries, the Mazovian Empire had waged war against Baltic pagans, pushing them further north. On behalf of Jakub II, Henryk sent a formal request to the Holy See for permission to launch a crusade against the Livonians. Pope Theodorus IV approved the request, declaring a Crusade against the Pagan Kingdom of Livonia in the summer of 1261.

Faced with the threat of total annihilation, King Vaidginas II of Livonia took drastic action. He invited a Swedish bishop to his court, who baptized him and his entire family. In the following years, Livonian nobility also converted to Christianity.

This dynasty doesn't seem very stable, with only two male members left after Jakub... Wladyslaw and Odon are going to need to have plenty of sons to secure the dynasty's future.

I agree, but when I was playing it didn't occur to me and I went with the game's suggestion.His firstborn son should be named Henryk tbh in recognition of his great regent, uncle and stepfather

Królestwo Danii - Denmark Kingdom

Zakon Krzyżacki - Teutonic Order

Królestwo Liwońskie – Livonian Kingdom

Ruś Nowogrodzka - Novgorodian Rus'

Ruś Kijowska - Kievan Rus'

Królestwo Mołdawskie - Moldavian Kingdom

Królestwo Wołoskie - Wallachian Kingdom

Królestwo Bawarii - Bavarian Kingdom

1 - Duchy of Holstein

2 - Duchy of Brabant

3 - Duchy of Franconia

4 - Kingdom of Lombardy

5 - Kingdom of Carinthia

6 - Kingdom of Croatia

7 - Duchy of Chrobatia

8 - The Golden Horde

Wladyslaw seems to be the only remaining male member of the current dynasty, who would inherit if he were to die heirless?

That's a lot of pagan uprisings (I know it's counting rebellions against previous rulers of the Empire), will the Empire ever have an end to them?...