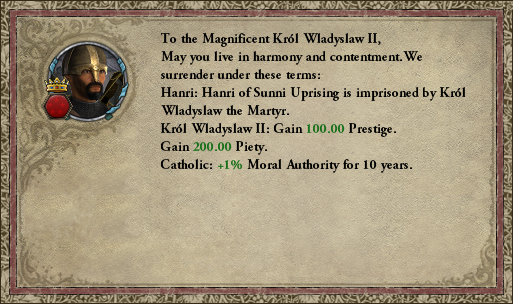

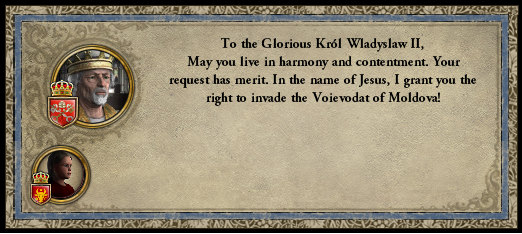

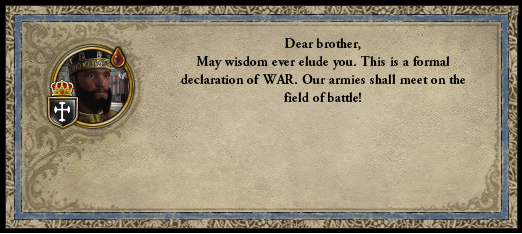

Thus, he resorted to a ruse, sending envoys to Chancellor Herbert with peace proposals: the young queen and her court would be spared and retain their health and lives, but she would have to renounce her royal title and all others, except for the Barony of Chișinău, which she could keep for herself and her descendants.

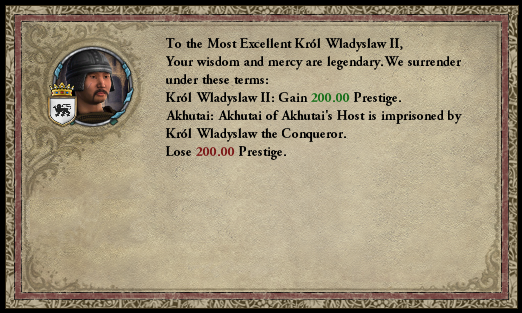

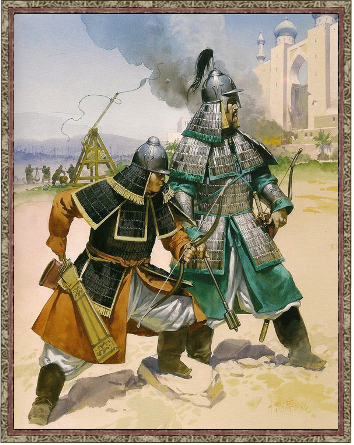

This offer was rejected, but Władysław’s envoys managed to bribe Moldavian mercenaries, who opened the gates to the Mazovian army. Street fighting lasted the entire day of March 12, 1380, and the capture of the palace ended the war. Władysław showed magnanimity—young Swietlana retained her barony, but all other titles passed to the Emperor of Mazovia. Chancellor Herbert, however, was executed. Moldavia was quickly transformed into a merchant republic dependent on the Mazovian Empire. Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi became the new capital, and the first Doge was Masław of Tomaszów Mazowiecki.