Not that there wasn’t good news to be had, as June, 1943, dawned.

Our military procedures were structurally improved in order to enable changes of orders in battle to be more efficiently carried out. This would help us to get an attack moving more quickly, even on the fly.

And we continued to load up more reinforcements to flood into the British theatre. Unfortunately, some of them were still across the world, and would take time to arrive. Others, however, were nearby, even if they were the substandard quality garrison divisions.

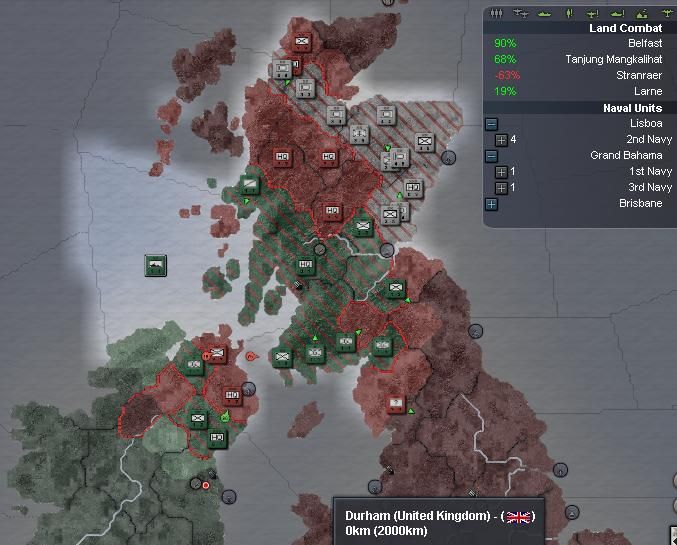

We needed all the help we could get. We were losing the battle in the Newcastle region, having lost the Battle of Morpath on 1 June. Our flank attack out of Kendal was ended, too, having lost much of its purpose. Those troops needed to rest and review how to best modify their approach with the changed situation.

The situation against the 51st Highlanders in the south could be rather easily handled, if we didn’t have a nearby situation with the British 4th Infantry at Stanraer, on the coast. Or vice versa. Handling both at once was proving a challenge.

We had the British 4th Infantry more or less contained, on the Scottish coast, except that they were just so strong, and our units were relatively light and weak. It was like having a tiger by the tail – you think you’d have some way to control them, but so much power was beyond what we could cope with.

The 22nd Infantry at Wigtown hit the 4th Infantry on their eastern flank, hoping to slow them down and preserve the garrison to the north. Gen. Cassels was a far better commander than those Portuguese generals arrayed against him, and his troops were veterans.

We did ultimately take Larne, in Ireland, where the 4th Infantry had recently vacated. But other things were conspiring against our victory. The British had apparently taken some lessons from the early days of our asymmetric warfare against them, and their mobile HQ detachments had cut off part of our conquests in the north, and were working to solidify their control again. They had brought in fighters to oppose our tactical bombers, making them far less effective and taking a toll upon them. The 4th Infantry had broken out of encirclement, and was moving forward along the coast.

And the 51st Highlanders had defeated the opposition in front of them, and had instead doubled back to flank our 21st Garrison Division at Kendal. This wasn’t going to end well. We needed reinforcements. Fortunately, they were on the way.

One garrison division was landed at Ft. William, on the coast west of Stirling, in order to stop the minor rampage the British Corps HQ was conducting. Another garrison division – the 13th – was landed at Ayr to cut off the escape of the 4th Infantry, and to further frustrate her very slow progress. For a tiger, she was moving very slowly, thanks to our various gambits we were laying against her.

We were growing increasingly concerned, actually, about the British 15th Infantry, trying to push her way south into Stirling, and presumably beyond into Rosyth or someplace where they could reconnect with British forces elsewhere. They apparently still had sufficient supply, somewhere – it could be supposed that since they were the only full division in the whole wide region of unoccupied Scotland that it would make sense on some level.

The 29th Division held out until late on the 6th, when they had to give up on their positions at Stirling and move south for the sake of self-preservation.

The 3rd Garrison Division, once it had stopped the British HQ unit on the coast, moved to then cut it off from friendly forces entirely by moving toward Crianlarich. Albeit at a snail’s pace, as garrisons are apt to do (they would not arrive until the 11th). Time would tell if it would be able to slow the advance of the British 15th into – or, potentially, out of – Stirling.

On the 5th, the 21st Portuguese Infantry Division was landed from the Irish Sea at Lancaster in order to lend support to the 21st Portuguese Garrison Division (not to be mutually confused!), which was being squeezed by the 51st Highlanders in the north and minor support units on their southern flank.

This support was too little, too late, as the 21st Garrison was essentially spent by that point. It made little difference with respect to the 21st Infantry, however, as she still had the ability to harry those HQ and support units, and could then move into a position to muscle the 51st Highlanders from the south, once they arrived in the Kendal area. That might just allow other units, in the north, to surround her and finally bring them to heel.

It was in the interests of making this happen that our navy dropped off another of our ubiquitous garrison divisions – the 10th – on the North Sea shore on the 51st Highlanders’ rear flank. This was not the end for the 51st – not just yet – as we had insufficient “real” strength in the region to pose a true threat to her existence, or even to her movements. But this was the start of the trap which would need to close upon her. More would develop in coming hours.

Additionally, the 22nd Garrison and 22nd Infantry Divisions (again, not to be confused) had successfully blocked in the British 4th Infantry again, holding her to her windswept perch on the coast. The 4th was actually suffering real losses, now, which slowed her martial march and tempered her dangerous temperament.

It seemed like the 4th might actually be at the end of her long, amazing run. But that remained to be seen.

The bad news was, after having carved out a huge proportion of Scotland without much opposition, Portugal now faced some relatively serious opposition on every front. Nevermind that that “relatively serious opposition” was in each case a single British infantry division on each front. The Portuguese Army was not really built to stand toe-to-toe with the British, which is why this was happening.

The only other good news of this period in the 1st week of June was that new factories opened back home in Portugal, in order to help carry the war industry effort further.

But if they have hard feelings, it's tough -- they need to focus on getting their OWN tanks pointed in the right direction!