1716-1732 That Troublesome Priest

The death of Sar Sarrani Levon in 1716 marked the opportunity for the Lebarian faction to finally contest the legitimacy of the Amarah-Laboue dynasty on the field as they had failed to in 1699. Capitalising on the assumed weakness of the new teenage Emperor Niv, and the unpopularity of his mother Sivert, the purported Lebario II raised the banner of rebellion in the Persian Gulf. Rallying the Bedouin Nestorian tribes of the region, he rode north into conservative Babylonia, where he found deep wells of support among the nobility, clergy and commonfolk alike. The pretender had high hopes of success as his numbers swelled, yet his lack of adequate artillery and stiff resistance from the city garrison prevented him from capturing Basra and sealing a solid base for his rebellion. In early 1717, he found himself isolated by a large loyalist army at the Battle of Najaf and badly defeated. As his supporters scattered, the would-be Emperor fled into exile in Persia.

The victors would not soon forget this revolt. Niv and his mother were already hostile to conservative elements at court and were suspicious at the enthusiasm much of the Church of the East in Babylonia and the Gulf had shown towards Lebario's claim. Fearing that the Nestorian hierarchy had conspired against them, they would push forward with reforms, that followed on from those of Levon, that would deepen the sidelining of the Church and seek a more secular state. This extended to inviting Jews and Muslims to take up roles in the Imperial administration.

Indeed, Niv and his mother were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment and ran something akin to a Bohemian court – patronising philosophers, artists and scientists and inviting them to advise on the business of state at the expense of traditional sources of authority. They would push forward with a number of reforms aimed at rationalising the realm, including an unpopular redrawing of administrative boundaries – which had hitherto been based on centuries old political units.

The most significant economic malady that the reformist court attempted to address was the debased Assyrian coinage. The primary coinage in the Assyrian Empire were the gold Dinara and silver Shekel, both minted by the crown in Nineveh. By the turn of the century both had been heavily debased by years of monetary mismanagement. However, these were not the only major coins circulating within the Empire. Owing to its historic privileges and status as an independent Kingdom prior to the Armenian-Assyrian union of the fifteenth century, Armenia had long held the right to mint its own coins – the Drum – a status it had retained even during the height of absolutism. Unlike the Imperial coins, the Drum had retained its metal content and by extension its value and become used widely through the Empire in the first decades of the eighteenth century.

The reformers hoped to both rationalise the coinage and restore its value and confidence. Seeing the Drum as undermining the authority of the central state and the Emperor's coin, they moved to close the Armenian mint – much to the anger of the northern elites – and ban the use of the Drum entirely. A new, high quality, Dinara and Shekel then began to be minted, which over several years would replace the existing debased coinage. This process, while successful in restoring price stability, was extremely expensive. The crown would take control over the production of the gold mines of Sumatra and the Cape and introduce a reformed code of taxation that would significantly increase state revenues by both eliminating a number of traditional exemptions and privileges possessed by the nobility and Churches and yet further increasing the burden on the rest of society.

While price stability was welcome, albeit implemented in an authoritarian way with many slow to trust the new coinage, and a particular boon to the rising urban economies of the Empire's great cities, the Assyrian peasantry, and particularly those of Mesopotamia, remained in a state of crisis and rising agitation. As the region continued to suffer under a prolonged dry spell that had greatly reduced yields, the nobility had moved to partially compensate themselves for the new tax demands of the state by asking for greater exactions on the peasants. In what had once been a comparatively affluent society, certainly in comparison to its counterparts in Europe, poverty was widespread and growing while thousands were forced to flee to escape hunger – whether to the cities or the colonies. Anger and social tensions were becoming acute.

While the ideas of the Enlightenment made their way through Assyrian society, they stimulated the birth of modern archaeology. Sitting atop the Cradle of Civilisation, enquiry into Assyria's ancient past had been somewhat limited up to the eighteenth century. Unlike Egypt, with its awe inspiring heritage visible for all the world to see, many of the wonders of Mesopotamia and the Levant were less well known and had left a comparatively weak cultural imprint. Indeed, many pious Christians were uncomfortable associating themselves with the Biblical villainy of the ancient pagan empires. However, the magnificence and grandeur of what some of the early archaeological pioneers found below the lands of Mesopotamia in particular would leave an indelible impression, sparking off a fashion among the free thinking middle classes for all things associated with the Ancients.

Out of this milieu enamoured with the discoveries of long lost civilisations in Babylon, Sumer, Assyria and Akkad, was an Armenian philosopher named Yanai Babai from the border city of Mus. Studying at the universities of Aleppo and later Nineveh, Babai put forward a set of genuinely revolutionary ideas. Criticising the inequities and illogicality of the existing order, Babai rejected not only the monarchy but aristocracy as well and even the role of religion in national life. He supported a democratic republican order, elected by those who contributed towards the national wealth, the elimination of archaic institutions, laws, obligations, privileges and superstitions in favour of an order based on reason, simplicity, equal treatment and justice. In his writings, with appealed to an imagined image of the glorious Ancients, who were ironically largely ruled by despotic empires, Babai spoke of the need for contemporary Assyria to “Pass through the Ishtar Gate”, a metaphor for a total transformation of society. It was with this passage in mind, that followers of his beliefs would form the Ishtar Club in 1725 as a forum in which to gather and expound their revolutionary ideas.

The most politically explosive element of the unconventional courtly life in Nineveh was its infiltration by a number of Sassinites. The idiosyncratic heretical movement had laid deep roots in Assyrian high society with a number of skilled social climbing adherents, while the mysteries of its idiosyncratic practises and freethinking challenge to traditional morality made it an attractive prospect to many – particularly in the atmosphere of Niv's court. Their presence, more than anything else, was completely intolerable to the Church of the East who could stomach neither their origins as a despised offshoot of their communion nor their debauched religious beliefs. Worse, the Dowager-Empress Sivert was known to be in an open affair with a Sassinites noblemen – earning her the popular epithet “The Whore of Babylon” among her critics. Patriarch Shimun pleaded with Niv to expel the Sassinites from his court and allow for a return of Christian values, but, given the frosty relationship between Church and crown, this was ignored.

This sore only deepened as rumours began to emerge in the 1720s that the Emperor, now growing into adulthood, had started to personally take part in some of the ceremonies of the Sassinites, including their mysterious sexual rites. In 1728 the teenage son of the Malik of Ilam came forward with a lurid tale of his own participation in one of these orgiastic rituals, during which the Sar Sarrani can committed homosexual acts with him. This was the final straw.

On Easter Sunday 1738, Patriarch Shimun took to his pulpit in Saint Addai's Chathedral in Nineveh to issue an extraordinary call to arms. He claimed that the Devil himself now ruled in Assyria, that the Emperor was a heretic, a sodomite and illegitimate rule; that his immorality and misrule was to blame for the woes befalling his people and named Lebario II as the true Sar Sarrani, pleading with him to return to Assyria to restore Christian rule. Not since the Marian Revolution had the Church taken such a stance of open rebellion. Few could have realised how ready the country was to erupt. Violence quickly engulfed the land. In the cities of Mesopotamia, Nestorian mobs waged pitched battles against minority communities – set large swathes of the region's great cities ablaze and massacring thousands while also attacking tax offices and administrative buildings and parading enormous crosses through the streets. More dangerously, agents of the pretender stirred massive peasant unrest into coherent rebel armies from the Armenian highlands in the north to the Gulf in the south as Lebario himself returned from Persia to take command of this second rising.

This revolt dwarfed the first Lebarian War a decade and a half previously. In its opening stages Niv was forced to flee his capital for Syria, while his allies were run out of Mesopotamia – with only a view brave urban holdouts in Nineveh, Baghdad and Samarra standing against the rebels. Regrouping in Aleppo, and having lost control of the Nestorian heartland which had served as a the bedrock of the Imperial regime, Niv was forced to turn towards the western periphery of his Empire to save him. The nobles of Syria, Armenia and Philistia realised their position of strength and would extract a heavy price for rally the energies of their peoples behind the Emperor in his hour of need. Niv would make grandiose promises of further autonomy, special rights for the minority Christian Churches, new tax exemptions and above all the reconvening of the Majlis just over a century after its bloody closure.

Niv's desperate offer to turn the clock back to something akin to the old Federal Kingdom had the desired effect. The Syrians, Armenians and Philistians swelled his weakened ranks in their tens of thousands, while the flower of the western realms' young nobility joined the war effort. With the Lebarians still struggling to subdue the three resistant cities in northern Mesopotamia, the loyalist army marched east with great confidence. Between 1729 and 1732, Niv's armies would reconquer Mesopotamia piece by piece, cutting through the sprawling peasant armies of the enemy with spite and precision in a long campaign culminating once more in Babylonia and a siege of Basra between 1731 and 1732. The bloody campaign would do significant damage to the already fragile and weakened agricultural system of the region and claim the lives of tens of thousands before Lebario would flee to Persia for the second time. After great sacrifice, the Emperor had defended his crown once more.

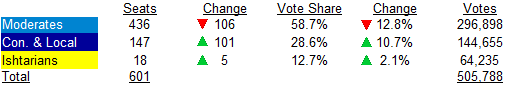

- 6

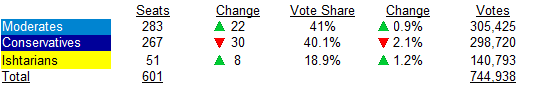

- 1