1744-1747 Justice and Terror

Following the murder of Vizier Ephrem Karim a small cabal of his most devoted followers took power. They were led by Nuri Ardalan, the Kurdish son of a shop-keeper from the city of Amin on the upper Tigris. Neither Ardalan nor his allies were great orators, theorists or visionaries, but they shared a relentless capacity for organisation and political fervour. Upon taking power, they swore before the Majlis to find justice for their fallen idol and to protect the revolution at any cost.

The mechanism with which the Ardalanites would carry out their cause had already been created during the premiership of Ephrem Karim – in the system of special courts he has established with the purpose of confiscating property from exiles and rebels. The new Vizier would transform this system of tribunals into a powerful weapon for the disciplining of Assyrian society and weeding out of reaction within the Republic. Between May 1744 and March 1745, a wave of purges, accusations and cold blooded political terror swept the lands under the authority of the Republic. The tribunals sought out any and all individuals believed to be in sympathy with the counter-revolutionary movements, bringing thousands of aristocrats, right-leaning politicians, actors in the state machinery and common people before their courts. Sentencing was carried out by Ishtarian militants and often resulted in death sentences for the accused. With accusation often enough to draw a conviction in itself, there was a flurry of score settling and paranoid confusion as individuals sought to send rivals before the tribunals before they themselves were taken.

The most prominent victims of this wave of terror was none other than the great general Nehor Vassak, who had saved the capital from the white army during the siege of Nineveh just two years before. Hailing from noble birth, having suffered recent military defeats at the front, having had a cold relationship with Karim prior to his death and being seen as a possible danger to the Republican regime itself; Vassak had a target on his shoulders from the first. Fortunately, the general was spared the indignity of execution – being sent to rot in prison near Lake Urmia. By the end of this wave of trials, several thousand death sentences had been carried out and fear had been imbued throughout the land.

It is notable that during this period, despite the viciousness of the purges, the regime was not completely closed to criticism. Notably, the Mardukites succeeded in tempering aspects of the Ardalanite terror – averting what might have amounted to an all out war against the Nestorian faithful. The Federal Republic and the Church of the East had been set against one another as enemies since the Patriarch had decanted to Baghdad and later Basra to align himself with the white army and the Lebarian cause in 1741. Since then, the Church had lost a number of its lands and properties, been stripped of any political influence or privilege, but importantly it had continued to serve its millions of parishioners within the territory of the Republic. The most extreme of Ishtarian radicals had sought to end this state of affairs, and strike against the Church and clergy with their whole might during the period of terror – seeing it as the ultimate enemy within, irrevocably lost to reaction. The Mardukite leader Lazarus Dunanu feared that this might spark open revolt in the countryside and the downfall of the Republic and therefore begged the governing faction to consider compromise.

In the years since the Patriarch's defection to the rebels, elements had emerged within the Nestorian clergy that were more accepting of the Republic. Dunanu therefore proposed cultivating these allies and pursuing a split between the Church within Republican territory and the exiled Patriarchate – providing a patriotic and republican leadership to the Church. With the backing of the regime, liberal clergy would hold a council in Nineveh in late 1744 – formally deposing the exiled Patriarch, deemed to have abandoned his seat, and appointing a replacement from among their faction. Nestorian had undergone the largest schism in its history. Yet these actions would spare it the wrath of the revolutionary tribunals.

Out in the Indian Ocean, the two poles of the Assyrian colonial empire remained bitterly opposed. In Sumatra and the Moluccas, Nineveh's offer of emancipation to slaves in 1742 had been contentious. Although slavery was not the basis of the economies of the East Indies, which relied predominantly on indigenous labour, there were still nearly 100,000 slaves in the colonies – a far larger number than had been emancipated within the Republican territories in the Middle East. While the issue divided the Sumatran assembly, that administered the wider region, the decision was taken to accept the demands of the 1742 constitution on the proviso that the freed slaves would repay their former creole masters for their lost property with an inheritable debt bond.

In the war, the Sumatrans had struggled to compete with the Lebarian Conservatives. The two most important centres of the Assyrian navy in Basra and Muscat were firmly in the hands of the whites, and this gave them the lion's share of the old Imperial fleet. With this strength, the Lebarians had been able to largely control Indian Ocean trade, while also pestering the the Indies with piratical raids. This naval strength had a disruptive impact on international trade – forcing both the Indies and Far Eastern economies to pursue longer and more perilous trade routes across the Pacific Ocean in order to reach European and American markets.

Despite their strong position in the Indian Ocean, the Lebarians would be menaced by the rising power of the Scots. Scotland had been the greatest winner of the colonisation of the Americas. By the early eighteenth century it had established three rich, populous and profitable centres of its empire in the Americas – New Scotland on the eastern seaboard of North America, the Caribbean and Brazil in South America, with less important holdings in Central and northern South America. The supreme power in the Atlantic World, in the early decades of the century that had grown ever more interested in Africa, the source of the slaves who were the basis of all three of their principle colonies' economies. This had resulted in the conquest of the Kongo Kingdom and establishment of territorial control into the Congo Basin. Ever eager for more sources of slaves, the Scots had enjoyed a profitable relationship with Assyrian intermediaries in the Cape to gain access to the East African trade as well. With Assyria in civil war, the Scots would turn more predatory – probing Assyrian defences in the Cape with raids and small scale attacks through the 1740s, forcing the Lebarians to maintain a sizeable garrison in the African colony and leading to the further militarisation of Alopheerian creole society.

The distraction of the Lebarians would prevent them from either seeking a direct assault on the Indies or concerning themselves with Malabar, Assyria's Christian Indian enclave that had been largely forgotten in the strains of the Revolution. The ruling St Thomas Christian community of Malabar had held little interest in the secular and democratic ideals of the Revolution, fearing the large Hindu minority they lived amongst, yet the failed to attract the support of the white army in Basra – who could not spare a garrison. Spying an opportunity to cast the Christians out, Malabar had faced a Tamil invasion in 1744 – with the Christians fleeing to their near impregnable coastal fortresses at Cochin and Vandad. Through the following years of siege, Malabar would sustain itself with little more than a trickle of supplies from Muscat.

As calm returned to the Republic within the end of the purges in early 1745, Ardalan's ministry looked to work towards the grandest exercise in democracy in world history. By 1745, the Majlis was an effective rump – its former royalist members had fled or been tried, many of those who remained in Nineveh represented areas that were not even under the control of the Republic. Unshakable in their faith in the masses, the Ishtarians were eager to implement the promise of universal manhood suffrage included in the 1742 Constitution and called for new elections to solidify their endorsement by the people. Coming out of the stifling atmosphere of the year of terror, open debate would ring out through the land once more as millions were given a say in their own governance for the first time.

With traditional conservatism unacceptable, the election saw a resurgence in previously moribund Federalist thought – with critics of the Republican regime framing their concerns in Federalist terms, seeking protection for the Churches, regions and individuals from the state and expressing preferences for elements of the 1738 Constitution over the Republican 1742 Constitution. Neo-Federalists would capture more than a third of the the vote and the second largest block in the Majlis. Lazarus Dunanu's moderate liberal faction would also fare well in the areas in which it stood candidates. The Ishtar Club was deeply disappointed, having expected to be greeted by the newly enfranchised masses with overwhelming support, they failed to secure an absolute majority in the chamber, reduced in size to account for the occupied territories. This poor showing would feed into a sense of unease and fragility at the centre.

The arrest of Nehor Vassak in 1744 had allowed for the young figure of Malik Abaya, hero of Aleppo and Baghdad, to be given command of the largest Republican army on the Anatolian front. There, he would meet with outstanding military success. Over the course of an incredible campaign between 1744 and 1746, Abaya would utterly destroy the Byzantine army and their Assyrian Imperialist allies, occupying the entirety of Asia Minor and even shelling Constantinople itself from across the Golden Horn. These victories effectively ended the immediate threat to the survival of the Republic and earned him widespread popular support in Assyria itself, where the cold leadership of Ardalan and his clique had been struggling to reignite mass support. Crowing fearful of Abaya's influence, and motivated by the same suspicions and jealousies that had led to the arrest of Vassak in 1744, Abaya was recalled from his command in 1746 and assigned to a much smaller military force responsible for eliminating the raids of Bedouin tribes striking through the Syrian Desert who had been wreaking havoc with agriculture in Syria and Mesopotamia.

During this period, other fronts in the civil war remained more static. In Babylonia, Republican forces launched a number of raids aiming to stimulate slave unrest with the offer of emancipation, but achieved only limited success with the whites mostly able to keep them at bay. The one major success for the Republic in this theatre was the capture of Muslim-majority Najaf in 1745 – taking advantage of the weaker presence of a hostile, pious and militant Christian majority. Elsewhere, there were gains in the Levant, where long and grinding sieges at Beirut and Damascus saw souther Syrian regained by the Republicans and revolutionary forces begin to push on towards the medieval fortresses of Philistia itself.

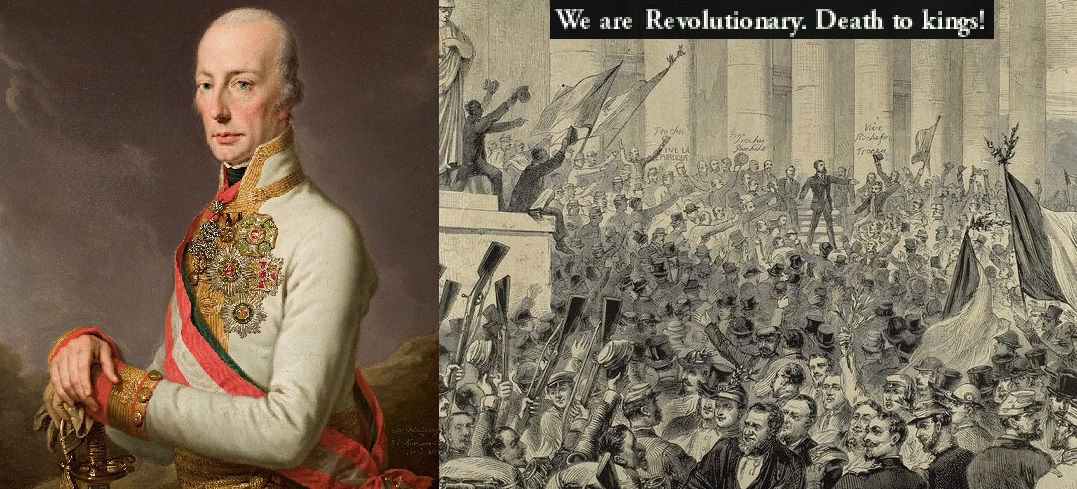

The Assyrian Revolution marked a world historic moment, from the early stages of its development the revolutionary ideals that powered it – liberalism, constitutional government and equality – spread out across the civilised world. By the 1740s, they were beginning to make their mark in Europe and Asia. In the Byzantine Empire, the conduit through which many European Enlightenment ideas had first reached Assyria, many of the urban middle classes were attracted to liberal ideas, but it was the military successes of the Assyrian revolutionaries in the mid-1740s that pushed them to the forefront. In Anatolia, the victorious Assyrian armies had established elected local councils and encourages revolutionary reforms in the areas they occupied. Across the Aegean and Black Seas, thousands liberal factions were forming in Greek cities opposed to the policy of the Emperor while ethnic minorities rallied before revolutionary banners to seek their freedom. The destruction of much of the Byzantine army by Malik Abaya's campaigns left the Empire vulnerable and in 1745 the Albanians, who had been in revolt for years, would successfully establish a revolutionary Republic centred on Vlore. Two years later the Russians living on the Byzantine enclave east of the Kerch Strait established their own Republic, while in Wallachia Romanian rebels dominated the Danube.

To the east, liberalism was rising throughout the cities of Persia, causing significant concern for the Timurid Great Khan whose initial delight in the downfall of the Assyrian Empire was increasingly turning to fear and dread. To the west, in the Kingdom of Italy fear of revolt and extensive agitation led to the end of feudalism and absolutism with the adoption of a democratic constitution in 1743 and the establishment of friendly relations with the Assyrian Republic – doing much to relieve its chronic geopolitical isolation. Across Europe movements for change were growing in strength and adventure, most importantly beyond the Alps in Germany.

The greatest legacy of the Assyrian Revolution beyond its own borders, certainly in the short term, was the German Revolution. As one of the most economically and culturally advanced areas of Europe, liberal ideas were already present in Germany long before the advent of the Assyrian Revolution. Yet it would be the inspiration of the Near East that would drive the German masses and their leaders to turn to action. The victory of the revolutionaries at the Siege of Nineveh in 1742 was celebrated by liberals around the world. In the Kingdom of Thuringia, which ruled over the largest part of Germany, it drove key liberal leaders to form their own Teutonic Ishtar Club – which adopted the 1742 Assyrian Constitution as its manifesto. In 1746 the group orchestrated a large uprising in the Kingdom's key cities and, benefiting from widespread sympathies within the army, overthrew the monarchy and seized control of the Kingdom. A key demand of the Teutons was the unification of the German lands – which were divided between Thuringia, the remnants of the Holy Roman Empire, the Baltic Duchy of Rana and several smaller states, mostly under French influence. Having been a committed member of the coalition fighting the Assyrian Revolution, the French were terrified of the rise of an aggressive Republic on their frontier and in the heart of Europe and would soon invade to support the forces of German counterrevolution, drawing in their allies in the neighbouring Kingdom of Croatia – whose boundaries snaked from the Adriatic to the Baltic.

The German Revolution would have important strategic consequences in the Middle East, with the French forced to effectively abandon their Catholic clients in the Kingdom of Egypt and Jerusalem as they desperately hurried troops back across the Mediterranean, leaving the Levantine front exposed and vulnerable. More importantly, it made clear that the ideals of the Assyrian Revolution were universal and exportable. There was not a single crowned head in the advanced world who could rest easy upon on the authority of tradition alone.

Although by the end of 1746 the Republic was more secure than it had been since its proclamation, the governing clique felt more threatened and insecure than at any time since the end of the terror. By then a new wave of panicked accusations and trials were beginning to pick up steam, with a fear of spies and traitors gripping Nineveh. One arrest would be more explosive than any other. On 6 February 1747, within the chamber of the Majlis itself, one of the Vizier's close allies delivered a speech in which he provided lurid details of a plot between none other than the Mardukite leader and former titan of the Ishtar Club Lazarus Dunanu was in league with the Timurids to spring general Nehor Vassak from his imprisonment near the Persian border and lead a military coup to overthrow the regime. Before he could speak in his defence, soldiers entered the chamber and dragged Dunanu away in chains. In a hasty trial lasting just a couple of days, Dunanu was brougth before the tribunal, found guilty and sentenced to death. The revolutionary crowds of Nineveh who once followed his every word came out in their tens of thousands to delight in his public execution, while in distant Urmia his alleged co-conspirator Vassak met a similar fate at the hangman's noose.

The turn against two of the greatest heroes of the revolution was shocking and drove the very sort of conspiracy that Ardalan and his allies feared. Believing that they would be the next targets for the revolutionary tribunals, a secret coterie of Mardukite, Federalist and even more moderate Ishtarians would send an appeal to Malik Abaya, asking that he lead his troops to the overthrow of the sitting Vizier and act as a popular figure head for a government of unity. A personal admirer of Dunanu, Abaya agreed and led the small army of a few thousand soldiers he had under his command to the capital at the end of February. Despite the efforts of Ishtarian radicals to organise popular resistance to this coup, attempts to barricade the city devolved into brawling between rival Republican factions and allowed Abaya's troops to move swiftly on the Majlis – occupying the legislature and arresting Ardalan and his closest allies. The most radical phase of the revolution was over.