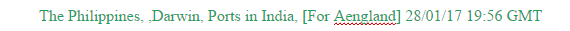

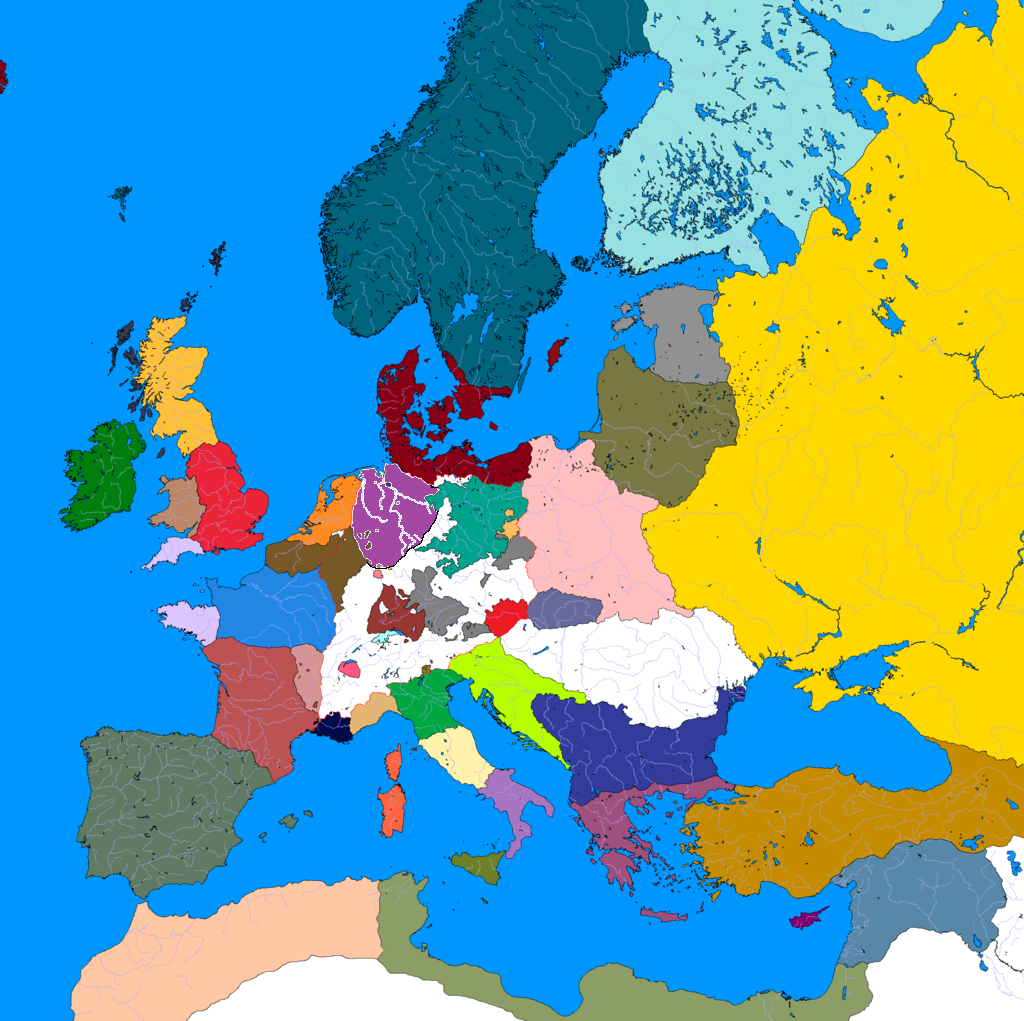

((You did actually check the world document, right?))Here's a consolidated map of Europe.

-------------

Welsh Holdings in Asia

(anti-clockwise from Mumbai)

Official Name: United Provinces and Territories of the Royal East Indian Company of Wales [CIDC]

Common Name: Various; India (when spoken in a Welsh context) or Welsh India common

Capital: Gwyr [Goa]

Company Headquarters: Caernarfon

Head of State: Directors of the Royal East Indian Company of Wales

Head of Government: Various; Governor-General in each province

[Population data to come]

Location: Mumbai, Goa, Chittagong

[History to come]

-------------

Official Name: Governate of Hong Cong

Common Name: Hong Cong

Capital: Hong Cong

Head of State: King of the Welsh

Head of Government: Lieutenant-General of Hong Cong

[Population data to come]

Location: Hong Kong, Kowloon

[History to come]

-------------

Official Name: Governate of the Islands of New Anglesey [Môn Newydd]

Common Name: New Anglesey [Môn Newydd]

Capital: Porth Iuan [Manila]

Head of State: King of the Welsh

Head of Government: Lieutenant-General of New Anglesey

[Population data to come]

Location: Palawan, Mindoro, Manila Bay

[History to come]

-------------

Official Name: Governate of the Territories of Awstralia

Common Name: Awstralia

Capital: New Cardiff (Caerdydd Newydd) [Sydney], capital of New Glamorgan[1] (Morgannwg Newydd); Fychan (Vaughan) [Perth], capital of New Pembroke[2] (Benfro Newydd)

Head of State: King of the Welsh

Head of Government: Lieutenant-General of the Territories of Awstralia

[Population data to come]

Location: 1: New South Wales, Victoria, Kangaroo Island; 2: Perth and hinterlands

[History to come]

[Map Game] Novus Ordo II (POD - 1066)

- Thread starter Firehound15

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

((You did actually check the world document, right?))

All it tells me is that Moldova is taken.

In which case, unless you are intent on having ever single Philippine island under your control, it seems there is no issue.

Oh no, it's not like the Manila bay is the entire nexus for the Philippines. I am disappointed DB, I expected you to respect order and proper protocol.

Oh no, it's not like the Manila bay is the entire nexus for the Philippines. I am disappointed DB, I expected you to respect order and proper protocol.

I have already explained that the claims document is not working for me, so let's wait a minute before invoking the disappointment line, shall we? This is what is known as a misunderstanding. This is no malicious land-grab.

Two things are important here: one, that Wales’ presence in Manila Bay is actually incomplete if you look closely. Indeed, actual Manila is still unclaimed as far as I'm concerned (and I've edited my post to clarify this). Two, there is in any case no reason whatsoever why Manila must remain the Philippine nexus in this world.

As I say, however: if you are intent on controlling every last Philippine, I will not stand in the way of your claim.

1. Be civil OOCly. The last thing we need is a big scuffle between players.

Let's not get into fights over claims. Frankly, there's no reason to, and it bogs down the game regardless.

DB, if you need to know what is claimed, you can send any of us a PM and we will tell you what is claimed/add the claim for you.

Sealy, let's refrain from using an exorbitantly large font to accentuate points. I understand that this violates your claim, but there are far more appropriate means to deal with this sort of thing, including speaking to me about it. (Not to mention that DB's post isn't actually official until he writes the histories, anyway.)

ANGLISK TERRITORIES IN ASIA [Red]

Common Name: The Evardians, Andhra Pradesh, Kagoshima, Penang.

Capital: Manilla, [regional administration also used]

Company Headquarters: London

Head of State and Government: Lieutenant Governor Johann Sigurdson.

Demonym: Evardian, local regional terms.

Languages: Anglisk, Japanese, Hindi, Arabic, Edvardian Tongues, Malaya.

Ethnic Groups: See Above.

Religions: Exact figures unknown, Catholic, Hindu, Shinto, Islam

Population: 0.5-3m [estimates vary due to the unkown population of the Evardians]

Location: The IRL Philippines, Andhra Pradesh coast, Kagoshima.

History: The Anglisk Territories are some of the land remnants of the Anglisk empire, built to funnel goods and trade back to the homeland. The ports of the Indian Coast; most notably Haroldston, link to the far east and serve as the economic driver of much of Ængland's growth. It's strategic positioning allows it to have a foothold in this area and secure many of the goods coming back to Northern Europe to go through the ports of Winchester or London, rather than Glasgow or Dundee. Out here, it has quite clearly bested the Scots out of any ability to control trade, although conflict with privateers is quite common. It also seeks to align itself with the Adulesians, as a bulwark against Aquitaine; who is one of the main naval enemies of Ængland back in Europe. Ængland's main trump-card in this region is the port of Kagoshima, which gives ie neigh-dominance over trade with the Japanese. Kagoshima was only acquired recently under a mutual lease (one that required Ængland to pay dues to the government in Edo)

SCOTTISH TERRITORIES IN ASIA [Yellow]

Common Name: See-Ec

Capital: Local sub-divisions in Thiruvananthapuram, Perth & Malacca

Company Headquarters: Dundee.

Head of State and Government: Lieutenant Governor Robert Davidson

Demonym: Secer, local demonyms.

Languages: Scots, Malay, Malayalam, Aboriginal tongues around the settlement of Perth.

Ethnic Groups: Scots, Malay, Southron Indians, Australian Aborigines.

Religions: Kirk o' Scots, Catholic, Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, Aboriginal religions.

Population: Not accurate population estimate exists.

Location: IRL Perth (and surrounding areas), Thiruvananthapuram and Malacca.

History: The SEIC was an attempt of the Scottish government to counter the attempts of both the Anglisk and Welsh attempts in the region. It was a late starter, not getting the proper funds for any kind of serious action until the 1734; which by then it was far behind its competitors in the region. It is quite a small collection of holdings, with two trading ports and a colony on the Western Tip of New Fife. It is quite a weak power, and is mostly a part of Scotia's ephemeral claim in the region. it didn't even have the power to oust the Anglisk during the wars of coalition, and is more a trophy than a critical part of the European economy.

DB, if you need to know what is claimed, you can send any of us a PM and we will tell you what is claimed/add the claim for you.

Will do, thanks.

The histories are up, for what it's worth. This includes those for the disputed lands, now scattered as Anglo–Scottish spoils of war, purely for the dual reasons that I'm a completist who can't edit his map at the moment. I will revise as you see fit, Fire (and as and when I'm able to get some time on Photoshop).

Disregarding the fact that many of your claims overlap with others, the sheer amount of territory Wales has is simply improbable. In a world with six major competitors for colonies (Andalusia, Aengland, Lotharingia, France, Aquitaine, Scotland) compared to OTL three (France, UK, Spain), and four minor competitors (Denmark, Ireland, Brittany, Holland) compared to OTL two (Portugal and Netherlands), there simply isn't enough room for colonially irrelevant nations like Wales to claim their place in the sun.Will do, thanks.

The histories are up, for what it's worth. This includes those for the disputed lands, now scattered as Anglo–Scottish spoils of war, purely for the dual reasons that I'm a completist who can't edit his map at the moment. I will revise as you see fit, Fire (and as and when I'm able to get some time on Photoshop).

Especially when you say the holdings in Asia are minor compared to the " bulk of Welsh colonial holdings... situated in the Western Hemisphere," it just seems utterly unrealistic. Perhaps Wales may have had minor colonial ventures (as much as a nation of 1 million can support) to varying degrees of success in the early days of colonialism, but after three hundred years of war and diplomacy, one or more of the larger powers most definitely would have gobbled up Wales' colonial holdings.

Disregarding the fact that many of your claims overlap with others, the sheer amount of territory Wales has is simply improbable. In a world with six major competitors for colonies (Andalusia, Aengland, Lotharingia, France, Aquitaine, Scotland) compared to OTL three (France, UK, Spain), and four minor competitors (Denmark, Ireland, Brittany, Holland) compared to OTL two (Portugal and Netherlands), there simply isn't enough room for colonially irrelevant nations like Wales to claim their place in the sun.

Especially when you say the holdings in Asia are minor compared to the " bulk of Welsh colonial holdings... situated in the Western Hemisphere," it just seems utterly unrealistic. Perhaps Wales may have had minor colonial ventures (as much as a nation of 1 million can support) to varying degrees of success in the early days of colonialism, but after three hundred years of war and diplomacy, one or more of the larger powers most definitely would have gobbled up Wales' colonial holdings.

I really don't have any desire whatsoever to get into this discussion. For what it's worth, I disagree (obviously), but seeing as it's quite clear that I've offended you all, unless Fire gives any indication that it would be uncessary, I'll remove the post and wash my hands of this whole affair.

... it's quite clear that I've offended you all,

I'm perfectly fine with what you've got there. Ængland got trashed pretty badly in the 18th century by other british nations, perfectly reasonable you picked up some stuff there.

Map:

[Uhhh....]

Official Name:

Regnum Hungariae| Magyar Királyság| Kingdom of Hungary

Common Name: Hungary

Capital: Buda

Head of Government and State: King János II

Demonym: Hungarian

Languages: 57% Hungarian, 6% German, 30% Romanian(Primarily in Transylvania, 5% Slovakian, 1% Croatian, 1% Other

Ethnic Groups: 59% Hungarian, 4% German, 30% Romanian, 5% Slovaks, 1% Croat, 1% Other

Religions: 36% Roman Catholic, 12% Anabaptist, 22% Volvantist, 30% Eastern Orthodox (Mainly Romanian), >1% Other

Population: 9 million

Location: OTL Kingdom of Hungary, minus Croatia and Slovakia

History:

The Kingdom of Hungary was founded by King Stephen I in 1000 and shortly after his death, the Kingdom entered a period of instability that did not end until the reign of King Béla I from 1060 to 1063. After his death, Béla's nephew Solomon would assume the throne with the aid of the Holy Roman Empire. Under Solomon, Hungary entered a period of conflict with many neighboring nomadic tribes as well as briefly with the Byzantine empire. Solomon was overthrown by his cousin Géza 1074 and during his reign would form better relations with the Byzantines, but he died just 3 years later and was succeeded by his brother Ladislaus. Ladislaus consolidated his power in Hungary and embarked on several campaigns of expansion, most notably claiming the throne Croatia in 1091 (though the two kingdoms would be governed separately for the duration of the union). Ladislaus died in 1095 and was succeed by his nephew Coloman. Coloman attempted to secure his hold on Hungary but his armies were defeated in 1097 by the forces of King Peter II, losing control over Croatia in its entirety. Coloman would be overthrown by his brother Álmos in 1105.

King Álmos' I reign marked the beginning of another period of instability, due in large part to the extensive efforts of Coloman and later his son Stephen to reclaim the crown. Álmos would be succeeded by his son Béla II after his death in 1129. Stability would once be returned under Béla's reign, but only after a series of violent and bloody purges. During his reign, Béla II would embark on further campaigns of expansion as well as strengthened relations with the Holy Roman Emperor. Béla II died in 1141 and was succeeded by his son Géza II. Géza would fight an inconclusive war with Byzantines as well as defeat the pretender Boris who invaded with an army of German mercenaries. He would be succeeded by his son King Stephen II after his death in 1162. The 15-year-old King was soon set up by Byzantine forces who hoped to install his uncle, also named Stephen, onto the Hungarian throne. However, the Byzantines were defeated in 1164 and the young maintained control over Hungary. Stephen II would fight continued wars with the Byzantines until 1167.

Stephen's brother and successor Béla III would continue to take advantage of the weakening Byzantine Empire until the succession of Bulgaria in 1187. The Hungarian crown would, however, take the opportunity to invade the newly independent Bulgaria, taking Belgrade in 1223. Conflict with the Bulgarians would continue intermittently causing a rivalry to form between the two nations. Hungary would soon, however, face a grave threat in the form of the Mongol invasion. The nomadic invaders would ravage Hungary's cities and countryside, encouraging the Hungarians to build up the nation's defensives. Recovering from the event quickly and once again becoming a formidable regional power.

The ruling Arpad dynasty would die out in 1301, and the claimant Wenceslaus of Bohemia was crowned king, however power was held by the various autonomous oligarchs within the Kingdom. His "rule" was brief though as he lacked the support of the majority of the oligarchs, who soon began vying for power. This conflict would not end until 1323 when the various local lords came up a compromise. For the next two centuries, Hungary was ruled by various weak monarchs while the oligarchs maintained their own de-facto independence. This period would come to an end in 1526 when Stephen Kán, the Voivode of Transylvania claimed the Crown. This sparked a civil war as the western Oligarchs disputed the claim. While the conflict would officially end in 1532 the Kingdom would remain divided as attempts by the new royal family to consolidate power would be continuously rebuffed. Hungary would not be reunited until 1731 when the First March of Sartaq Khan led to the creation of a tributary state in Hungary. This was soon overthrown after Khan had left Central Europe. Again Hungary grew in power until in the late 18th century, they fought a devastating war with Poland resulting in Hungary being forced to give independence to the Duchy of Nitra. Today Hungary is a formidable if still recovering Kingdom and there are many who want to see its losses regained.

Flag:

[Uhhh....]

Official Name:

Regnum Hungariae| Magyar Királyság| Kingdom of Hungary

Common Name: Hungary

Capital: Buda

Head of Government and State: King János II

Demonym: Hungarian

Languages: 57% Hungarian, 6% German, 30% Romanian(Primarily in Transylvania, 5% Slovakian, 1% Croatian, 1% Other

Ethnic Groups: 59% Hungarian, 4% German, 30% Romanian, 5% Slovaks, 1% Croat, 1% Other

Religions: 36% Roman Catholic, 12% Anabaptist, 22% Volvantist, 30% Eastern Orthodox (Mainly Romanian), >1% Other

Population: 9 million

Location: OTL Kingdom of Hungary, minus Croatia and Slovakia

History:

The Kingdom of Hungary was founded by King Stephen I in 1000 and shortly after his death, the Kingdom entered a period of instability that did not end until the reign of King Béla I from 1060 to 1063. After his death, Béla's nephew Solomon would assume the throne with the aid of the Holy Roman Empire. Under Solomon, Hungary entered a period of conflict with many neighboring nomadic tribes as well as briefly with the Byzantine empire. Solomon was overthrown by his cousin Géza 1074 and during his reign would form better relations with the Byzantines, but he died just 3 years later and was succeeded by his brother Ladislaus. Ladislaus consolidated his power in Hungary and embarked on several campaigns of expansion, most notably claiming the throne Croatia in 1091 (though the two kingdoms would be governed separately for the duration of the union). Ladislaus died in 1095 and was succeed by his nephew Coloman. Coloman attempted to secure his hold on Hungary but his armies were defeated in 1097 by the forces of King Peter II, losing control over Croatia in its entirety. Coloman would be overthrown by his brother Álmos in 1105.

King Álmos' I reign marked the beginning of another period of instability, due in large part to the extensive efforts of Coloman and later his son Stephen to reclaim the crown. Álmos would be succeeded by his son Béla II after his death in 1129. Stability would once be returned under Béla's reign, but only after a series of violent and bloody purges. During his reign, Béla II would embark on further campaigns of expansion as well as strengthened relations with the Holy Roman Emperor. Béla II died in 1141 and was succeeded by his son Géza II. Géza would fight an inconclusive war with Byzantines as well as defeat the pretender Boris who invaded with an army of German mercenaries. He would be succeeded by his son King Stephen II after his death in 1162. The 15-year-old King was soon set up by Byzantine forces who hoped to install his uncle, also named Stephen, onto the Hungarian throne. However, the Byzantines were defeated in 1164 and the young maintained control over Hungary. Stephen II would fight continued wars with the Byzantines until 1167.

Stephen's brother and successor Béla III would continue to take advantage of the weakening Byzantine Empire until the succession of Bulgaria in 1187. The Hungarian crown would, however, take the opportunity to invade the newly independent Bulgaria, taking Belgrade in 1223. Conflict with the Bulgarians would continue intermittently causing a rivalry to form between the two nations. Hungary would soon, however, face a grave threat in the form of the Mongol invasion. The nomadic invaders would ravage Hungary's cities and countryside, encouraging the Hungarians to build up the nation's defensives. Recovering from the event quickly and once again becoming a formidable regional power.

The ruling Arpad dynasty would die out in 1301, and the claimant Wenceslaus of Bohemia was crowned king, however power was held by the various autonomous oligarchs within the Kingdom. His "rule" was brief though as he lacked the support of the majority of the oligarchs, who soon began vying for power. This conflict would not end until 1323 when the various local lords came up a compromise. For the next two centuries, Hungary was ruled by various weak monarchs while the oligarchs maintained their own de-facto independence. This period would come to an end in 1526 when Stephen Kán, the Voivode of Transylvania claimed the Crown. This sparked a civil war as the western Oligarchs disputed the claim. While the conflict would officially end in 1532 the Kingdom would remain divided as attempts by the new royal family to consolidate power would be continuously rebuffed. Hungary would not be reunited until 1731 when the First March of Sartaq Khan led to the creation of a tributary state in Hungary. This was soon overthrown after Khan had left Central Europe. Again Hungary grew in power until in the late 18th century, they fought a devastating war with Poland resulting in Hungary being forced to give independence to the Duchy of Nitra. Today Hungary is a formidable if still recovering Kingdom and there are many who want to see its losses regained.

Flag:

Official name: Kingdom of Hannover/ Königreich von Hannover

Unofficially: Hannover

Capital: Dortmund

Head of State/Government: Ludwig Billung-Marburg

Demonym: Hanoverian

Language: Westphalian 76% Other German 14% Frisian 7% Other (Dutch, Danish, French, Aenglisc)

Religion: Jansenist (42%) Synergist (36%) Catholic (10%) Other Protestant (8%) Jewish (4%)

Pop: 6.1 Mil

Map: (Terribly drawn, I know!)

Flag:

.svg.png)

An absolute monarchy, the Kingdom has no legislative chambers to speak of.

More detailed land claims: Entire Imperial-Dutch border, follows the Rhine south to Mainz/Frankfurt, but excluding Mainz/Frankfurt, Excludes Dusseldorf. All of Hesse/Brunswick, not Anhalt/Magdeburg, Includes Lunenburg, Follows the current Danish border, excludes Bremen/Hamburg.

In 1110, Ulrich Billung, duke of Saxony, son of Magnus and Sophie of Hungary, wed Hedwig of Gudensberg, heiress to Hesse and Gudensberg. This made Ulrich an extremely powerful figure, and he led an uprising against Emperor Heinrich V in 1120 when Heinrich leveled a new tax, which the Emperor put down. Ulrich was stripped of much of his eastern lands and his title, which would end up with the Ascanians. After reconciling with the Emperor, he was recognized as Duke of Braunschweig. Still one of the greatest lords of the Empire, Ulrich was elected Emperor upon Heinrich’s death without an heir in 1125. Heinrich’s lands, however, were set to be inherited by his nephew Friedrich Hohenstaufen of Swabia. Ulrich considered the Hohenstaufens his bitter rivals and sought to prevent the inheritance by issuing a ban against the Duke of Swabia, leading to conflict within the empire. Ulrich had some successes, but failed to entirely impose his will. Still, he managed to gain the northern portion of the Salian lands when he made peace with the Swabians. The rest of Ulrich’s reign was devoted to affairs in Italy and a failed crusade against the Sicilians.

A relatively unpopular emperor, after Ulrich’s death in 1137 the Imperial crown passed to his Hohenstaufen rivals and his many lands were divided between his two sons, and even more thoroughly divided among his grandsons. Through marriage, the Bavarian Welfs managed to inherit a decent portion of Ulrich’s lands, giving them a power base with which to recapture Bavaria. So divided, the political influence of the Billungs in the empire faded. Despite the political insignificance several communities within the greater Billung/Welf dominion grew wealthy trading with merchants from Bremen and other Hanseatic cities.

Things began to change when Dietrich Billung-Osnabruck invited a large community of Aenglisc “Lollards” to settle in his newly conquered east-Frisian territory in 1404. Soon the area began to attract heretics from all over Europe. The theological debates at the nearby newly-founded University of Osnabrück became extremely heated, but relatively quickly a reformist consensus developed. Following the execution of Jan Hus, the consensus grew increasingly radically separatist. For harboring such dangerous heretics, Otto Welf, Duke of Westphalia, successfully had Dietrich excommunicated and banned and led a coalition to seize his lands. Even after a bloody uprising was put down by Duke Otto, he failed to entirely eradicate the heretics, and reform-minded theologians continued to pour out of Osnabruck.

FInally, a monk from Saxony residing in Kassel nailed several Theses regarding the sale of indulgences to a local church door, causing an uproar. The monk was promptly excommunicated and executed, but in his wake other reformers sprung up and the religious situation in whole region spiraled out of control. Many local rulers broke with the church entirely and local reformers began to organize new congregations. Most loyal Catholic rulers had their lands overrun, and shockingly, the Emperor Friedrich V refused to intervene. Coalitions of princes formed to crush the heretics, but the new zealous Protestant factions banded together despite various doctrinal differences, and motivated by religious zeal and employing tactically revolutionary lines of musketeers and wagonburg techniques repulsed all invaders.

The lone Catholic holdout in the region was the Elector of Braunschweig (who had seen Osnabruck added to his domains following Duke Otto’s crusade). Under Catholic ownership, many of the Osnabruck theologians fled to the new University of Marburg further south. In 1593, Kurfürst Albrecht Welf of Braunschweig died without an heir, triggering the religiously tinged Brunswickian Succession crisis between the Catholic Maximilian II Welf of Bavaria and the Protestant Niklaus Billung-Marburg of Hesse. Duke Niklaus ultimately prevailed, creating the new, and fairly large, and unrepentantly Protestant Electorate of Hesse-Braunschweig.

Many differing reformist movements developed in the region, organized by graduates of the Universities at Osnabruck and later Marburg. The Johannites, after Johann Eickenroth, rejected baptism at birth by arguing only a consciously faithful believer should receive baptism, and took a literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, forsaking all oaths, military and civil service in the corrupt world. The Johannites, known elsewhere as “anabaptists” spread far and wide across Europe and the new world, but never really caught on at home. The Neo-Hussites, or “Jansenists” embraced the doctrine of predestination, but kept many Catholic teachings regarding the Eucharist, and kept a church hierarchy in place, albeit one subordinate entirely to secular rulers. The “Synergists,” or “Schwartzerdians” rejected predestination, but believed in salvation through faith alone, and rejected Catholic teaching on feasts, saints and sacraments.

Grateful for his non-intervention in his war with Bavaria and subsequent confirmation as elector Kurfurst Niklaus controversially married his daughter Anna Katharina to Friedrich’s brother Karl Anton, the marriage requiring an elaborate “freedom of conscience” agreement for Anna. This only increased the anti-Swabian sentiment among the other princes, however. It would ultimately prove a valuable match at the start of the Carlian/Ottonian war, though as the dynastic connection led Kurfurst Niklaus to put aside his rivalry with the Bavarians to become the lone Northern prince to support the Swabian claim. The Billung-Marburg branch proved to be zealous Protestants, lending their armies to Protestant causes left and right, notably on behalf of the French kings, with whom they were heavily intermarried. Numerous Protestant refugees, especially Aenglisc, flooded into Niklaus’ lands.

In 1704, the house of Billung-Berg died out, and the Marburg line finally successfully reunited all of Duke Ulrich’s domains into one entity. In recognition of his service against the Tartars, Emperor Ferdinand recognized Kurfurst Wilhelm III Billung as King-Elector Wilhelm I of Hannover. Despite being named for Hannover, King Wilhelm built a new royal residence in Dortmund.

Despite being the birthplace of the reformation, the University of Marburg gradually shifted away from theology, allowing Munich to eclipse it in this field, and toward philosophy and mathematics. Talented graduates from all across the Empire and from outside of it flocked to teach there, and the region became a hotbed of liberalism. Notably, King Niklaus I, reigning 1761-1796, became known for his correspondences with intellectuals and authors across Europe. The model of an enlightened monarch, he instituted reforms guaranteeing freedom of speech, religion, and the press, and abolished torture. Highly interested in land use, he supported land reclamation projects, and made efforts to popularize new-world crops. He levied high tariffs on foreign goods, helping to develop industry in the cities within his domain. Despite these reforms, Hannover remains an absolute monarchy… for now.

Johanism never having been popular in the region, and giving its strong association with other parts of the Empire, Volontism hasn’t spread much in Hannover. With a local hotbed of enlightenment thought and a secularist bent to the current government, a strong anti-secularist push-back is certainly plausible, however, especially given the historical centrality of Protestantism to the region. The new King, Ludwig, grandson to Niklaus, is young and relatively untested, but his has so far shown himself to be more than happy to continue upholding his grandfather’s reforms.

Unofficially: Hannover

Capital: Dortmund

Head of State/Government: Ludwig Billung-Marburg

Demonym: Hanoverian

Language: Westphalian 76% Other German 14% Frisian 7% Other (Dutch, Danish, French, Aenglisc)

Religion: Jansenist (42%) Synergist (36%) Catholic (10%) Other Protestant (8%) Jewish (4%)

Pop: 6.1 Mil

Map: (Terribly drawn, I know!)

Flag:

.svg.png)

An absolute monarchy, the Kingdom has no legislative chambers to speak of.

More detailed land claims: Entire Imperial-Dutch border, follows the Rhine south to Mainz/Frankfurt, but excluding Mainz/Frankfurt, Excludes Dusseldorf. All of Hesse/Brunswick, not Anhalt/Magdeburg, Includes Lunenburg, Follows the current Danish border, excludes Bremen/Hamburg.

In 1110, Ulrich Billung, duke of Saxony, son of Magnus and Sophie of Hungary, wed Hedwig of Gudensberg, heiress to Hesse and Gudensberg. This made Ulrich an extremely powerful figure, and he led an uprising against Emperor Heinrich V in 1120 when Heinrich leveled a new tax, which the Emperor put down. Ulrich was stripped of much of his eastern lands and his title, which would end up with the Ascanians. After reconciling with the Emperor, he was recognized as Duke of Braunschweig. Still one of the greatest lords of the Empire, Ulrich was elected Emperor upon Heinrich’s death without an heir in 1125. Heinrich’s lands, however, were set to be inherited by his nephew Friedrich Hohenstaufen of Swabia. Ulrich considered the Hohenstaufens his bitter rivals and sought to prevent the inheritance by issuing a ban against the Duke of Swabia, leading to conflict within the empire. Ulrich had some successes, but failed to entirely impose his will. Still, he managed to gain the northern portion of the Salian lands when he made peace with the Swabians. The rest of Ulrich’s reign was devoted to affairs in Italy and a failed crusade against the Sicilians.

A relatively unpopular emperor, after Ulrich’s death in 1137 the Imperial crown passed to his Hohenstaufen rivals and his many lands were divided between his two sons, and even more thoroughly divided among his grandsons. Through marriage, the Bavarian Welfs managed to inherit a decent portion of Ulrich’s lands, giving them a power base with which to recapture Bavaria. So divided, the political influence of the Billungs in the empire faded. Despite the political insignificance several communities within the greater Billung/Welf dominion grew wealthy trading with merchants from Bremen and other Hanseatic cities.

Things began to change when Dietrich Billung-Osnabruck invited a large community of Aenglisc “Lollards” to settle in his newly conquered east-Frisian territory in 1404. Soon the area began to attract heretics from all over Europe. The theological debates at the nearby newly-founded University of Osnabrück became extremely heated, but relatively quickly a reformist consensus developed. Following the execution of Jan Hus, the consensus grew increasingly radically separatist. For harboring such dangerous heretics, Otto Welf, Duke of Westphalia, successfully had Dietrich excommunicated and banned and led a coalition to seize his lands. Even after a bloody uprising was put down by Duke Otto, he failed to entirely eradicate the heretics, and reform-minded theologians continued to pour out of Osnabruck.

FInally, a monk from Saxony residing in Kassel nailed several Theses regarding the sale of indulgences to a local church door, causing an uproar. The monk was promptly excommunicated and executed, but in his wake other reformers sprung up and the religious situation in whole region spiraled out of control. Many local rulers broke with the church entirely and local reformers began to organize new congregations. Most loyal Catholic rulers had their lands overrun, and shockingly, the Emperor Friedrich V refused to intervene. Coalitions of princes formed to crush the heretics, but the new zealous Protestant factions banded together despite various doctrinal differences, and motivated by religious zeal and employing tactically revolutionary lines of musketeers and wagonburg techniques repulsed all invaders.

The lone Catholic holdout in the region was the Elector of Braunschweig (who had seen Osnabruck added to his domains following Duke Otto’s crusade). Under Catholic ownership, many of the Osnabruck theologians fled to the new University of Marburg further south. In 1593, Kurfürst Albrecht Welf of Braunschweig died without an heir, triggering the religiously tinged Brunswickian Succession crisis between the Catholic Maximilian II Welf of Bavaria and the Protestant Niklaus Billung-Marburg of Hesse. Duke Niklaus ultimately prevailed, creating the new, and fairly large, and unrepentantly Protestant Electorate of Hesse-Braunschweig.

Many differing reformist movements developed in the region, organized by graduates of the Universities at Osnabruck and later Marburg. The Johannites, after Johann Eickenroth, rejected baptism at birth by arguing only a consciously faithful believer should receive baptism, and took a literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, forsaking all oaths, military and civil service in the corrupt world. The Johannites, known elsewhere as “anabaptists” spread far and wide across Europe and the new world, but never really caught on at home. The Neo-Hussites, or “Jansenists” embraced the doctrine of predestination, but kept many Catholic teachings regarding the Eucharist, and kept a church hierarchy in place, albeit one subordinate entirely to secular rulers. The “Synergists,” or “Schwartzerdians” rejected predestination, but believed in salvation through faith alone, and rejected Catholic teaching on feasts, saints and sacraments.

Grateful for his non-intervention in his war with Bavaria and subsequent confirmation as elector Kurfurst Niklaus controversially married his daughter Anna Katharina to Friedrich’s brother Karl Anton, the marriage requiring an elaborate “freedom of conscience” agreement for Anna. This only increased the anti-Swabian sentiment among the other princes, however. It would ultimately prove a valuable match at the start of the Carlian/Ottonian war, though as the dynastic connection led Kurfurst Niklaus to put aside his rivalry with the Bavarians to become the lone Northern prince to support the Swabian claim. The Billung-Marburg branch proved to be zealous Protestants, lending their armies to Protestant causes left and right, notably on behalf of the French kings, with whom they were heavily intermarried. Numerous Protestant refugees, especially Aenglisc, flooded into Niklaus’ lands.

In 1704, the house of Billung-Berg died out, and the Marburg line finally successfully reunited all of Duke Ulrich’s domains into one entity. In recognition of his service against the Tartars, Emperor Ferdinand recognized Kurfurst Wilhelm III Billung as King-Elector Wilhelm I of Hannover. Despite being named for Hannover, King Wilhelm built a new royal residence in Dortmund.

Despite being the birthplace of the reformation, the University of Marburg gradually shifted away from theology, allowing Munich to eclipse it in this field, and toward philosophy and mathematics. Talented graduates from all across the Empire and from outside of it flocked to teach there, and the region became a hotbed of liberalism. Notably, King Niklaus I, reigning 1761-1796, became known for his correspondences with intellectuals and authors across Europe. The model of an enlightened monarch, he instituted reforms guaranteeing freedom of speech, religion, and the press, and abolished torture. Highly interested in land use, he supported land reclamation projects, and made efforts to popularize new-world crops. He levied high tariffs on foreign goods, helping to develop industry in the cities within his domain. Despite these reforms, Hannover remains an absolute monarchy… for now.

Johanism never having been popular in the region, and giving its strong association with other parts of the Empire, Volontism hasn’t spread much in Hannover. With a local hotbed of enlightenment thought and a secularist bent to the current government, a strong anti-secularist push-back is certainly plausible, however, especially given the historical centrality of Protestantism to the region. The new King, Ludwig, grandson to Niklaus, is young and relatively untested, but his has so far shown himself to be more than happy to continue upholding his grandfather’s reforms.

Last edited:

Common Name: Nippon, Japan, Toyotomi Shougunate

Capital: Kyoto (home to the Emperor)

Osaka (home to the Shogun)

Head of Government: Toyotomi Hidekatsu, Shogun of Japan

Head of State: Emperor Kōkaku

Demonym: Japanese

Languages: 80% Japanese, 12% Korean, 2% Ainu,

Ethnic Groups: 78% Japanese, 15% Korean, 3% Ainu

Religions: 57% Shinto, 40% Buddhism, 5% Christian sects

Population: 23 m.

Location: Japanese Islands and the Korean peninsula

History: In the late 12th century, power transferred from the Imperial Court in Kyoto the Minamoto clan in Kamakura. The Shogunate which would be established by the clan. After the death of Yoritomo, the first Shogun, his young heir would be increasingly influenced by his mother from the Hojo clan, who ruled Japan through her children. The succession was chosen thereafter by the leaders of the Hojo family. The new shoguns, being puppets of the Hojo, were often chosen from the Imperial bloodline, to ensure legitimacy. This unusual system of governance worked out relatively well for Japan, ensuring peace after the takeover of the nation by the Minamotos

This was disturbed however when the Mongols under Kublai Khan attacked Japan. As the troops were transported by ships from Korea, a typhoon would batter and destroy many ships, and Mongol troops with them. When the troops from the mainland finally landed at Kyushu, the Japanese samurai were ready to fight. Fierce and bloody fighting would commence in Battle of Fukuoka, where the Mongols were defeated by the Samurai of northern Kyushu, although they inflicted severe losses to the disorganized force.

When the Khan heard of the failure of his attack, in his anger, he decided to muster an even larger force to attack the island nation. In 1281, a force of over 40,000 men set sail from Busan in Korea, while another force of 100,000 men was prepared in China. The Japanese were ready however, with defenses prepared. The outnumbered Japanese fought against Mongols, but the sheer numbers of the combined army drove them back. The Mongol would sweep up the now divided Japanese armies in a number of battles costly in men, but effective to say the least. The whole of island was controlled by the Mongols by fall of the next year. A similar story occurred in Shikoku, as the sheer numbers of the Mongols was able to defeat the Japanese in the mountains with similar losses. After a last ditch effort to stop the Mongol invasion by the Shogun, the Shogun surrendered to the Mongols.

The Gaikoku period, or the era where Japan was under Yuan rule, would be ultimately prosperous for Japan. Trade increased under the peace, and the population began to slowly grow again after the massacres of the conquest. The Emperor was allowed to stay as a sovereign, but only now as a King. He still stayed a popular figure in the eyes of Nipponese, being seen as a remnant of a free Japan.

The instabilities of the late Yuan period would be seen as an opportunity for the now-King of Japan. The man later known as Emperor Go-Daigo would rally support of the ambitious military governors which ruled Japan. The Yuan was unable to muster any significant resistance against the self-proclaimed Emperor due to a peasant revolt in China. Within a two year, the Imperial Family had a man sitting on the Chrysanthemum Throne again. The newly-crowned Emperor would immediately set out on his ambitions. His policies of a centralized state under the Emperor slighted many of his former allies.

These allies, chiefly the military governors led by Ashikaga Yoshiakira, would revolt in 1355. The war pitted loyalist forces against the military. The governors easily defeated the outnumbered loyalists. The governors installed a new Emperor in Kyoto, and got revoked many of the policies of Go-Daigo. The governors (whose land were now inheritable), would slowly grow in power and marginalize the court in Kyoto. These feudal lords,called daimyo, would become largely independent over the course of time. The next two centuries would see these warlords squabble over control of the islands. The bloodshed would only worsen with the introduction of guns by traders from Europe. Many daimyo attempted to unite the islands with their forces, however, only Toyotomi Hideyoshi would be successful.

Toyotomi's rise to power as a peasant have much to do with the attempts of the Oda clan to unite Japan. Their leader, Nobunaga, was almost successful in unifying the disparate states. He would be proclaimed as Shogun by the Emperor, but would die soon after. With his early death, Hideyoshi would finish this task and unite the islands again. He revived the title of shogun, establishing it the Toyoyomi Shogunate. His reforms in government and Japanese society as a whole would serve as the basis of the future law system of Japan. However, to most his most important contribution to Japan, other than its unification, was his invasion of Korea. The experienced Japanese army easily defeated the Korean armies, hampered by corruption in the Korean court. Hideyoshi wanted to use Korea as a base to invade China, but died before anything could come of it.

Japan under the new Shogunate, has thrived with the peace it brought. A cultural revival occurred with the peace of unification and patronage of the Shoguns, with new forms of art and poetry being invented. The population grew, and new techniques in farming has allowed the island nation to grow more food. Trade, along with the economic as a whole, also grew, with Europeans interested in Japanese wares. There have been few wars in this era on the island of Japan. But on the mainland in Korea, civil strife dominated as people defied to Japanese occupiers and their Japanification policies. Slowly, the Koreans were able to successfully rid the Japanese off their land, at least in the North, through several armed revolts. As of now, Japan is still a relatively powerful nation, but a backwards one. The Nation is still under a system of feudal governemnt, while much of the world is evolving into a new forms of governemnt. If Japan wishes to survive, then it will need to change itself, or it will be left behind by the world.

Official Name: The Patriarchate of Beth Hindaye

Common Name: The Patriarchate,Kodungallur

Capital: Kodungallur

Head of Government: Patriarch Ittyavirah III

Head of State: Patriarch Ittyavirah III

Demonym: Patriarchal

Languages: 100% Malayalam,40% Marathi,70% Sanskrit (Liturgical language)

Ethnic Groups: 60% Malayali,26% Pune Maratha,5% Other Indian,3% Arab/Persian,1% European

Religions: 70% St.Thomas Christian,15% Hindu,12% Muslim,9% Other Christian

Population: 63,726

Location: Kodungallur

History:

Avraham Yohannan Mathai (Malayalam അവ്രാഹം യോഹന്നാൻ മത്തായി) was born to Thoman a Merchant in Kodungallur and his wife Eliamma in 1289. He became an Ordained priest of the Church of St.Thomas in 1307 at the age of Eighteen where he requested permission from the Archdeacon himself to allow him to spread the word of Jesus Christ throughout India. After gaining permission he journeyed to the court of the King of Pandya Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I where he proselytized the faith of the lord to the local hindus.After numerous battles with the local brahmins he left the Pandya Empire’s borders with many of his converts to Karnataka where he gained many a convert in the region.He then settled in Pune eventually the christian population in Pune outgrew the local hindus.In 1337 Avraham died and was buried in the local Church he was made a saint by the Bishop of Beth Hindaye in 1347 just ten years after his death.In 1350 the local Raja started to persecute the local christians eventually culminating in the Nasrani Rebellion of 1353 and the Pune Christian exodus.The Pune Christians fled in droves down to Kerala where a large amount settled in Kodingallur the city where their saint was born.A Pune Christian by the name of Avaramji Raje Kale-Deshmukh a son of a Kshatriya from Pune who had converted to christianity led an insurrection against the Raja of Kodangillur with the support of the Pune Christian in 1367.After seizing Kodingallur he seized the surrounding cities of Allapuzha and Thiruvananthapuram beginning the Pune Raj and naming himself Chatrappati his successor Chatrappati Yonanaji I Raje Kale-Deshmukh continued his conquests of Kerala with his son Chatrappati Lukasji I Raje Kale-Deshmukh completing the conquest in 1407 with the conquest of Kasaragod.The Pune Raj dynasty gave Kodingallur to the church where the Archdeacon or Jathikkukarthavian of Kodingallur would have complete control over the city.The Arcdeacon of Kodingallur split with the Syriac Church in 1418 when a particularily violent civil war that lasted ten years occured in Assyria which effectively stopped communications between the two churches for sixty years. Jathikkukarthavian Skariah I Simha (The First Marathi Archdeacon) officially split ties with the Syriac Church and established the Patriarchate of Beth Hindaye with himself as the patriarch. The Patriarchs of Kodingallur would for the most part stay at peace and uninteresting acting similarly as to the Popes of Rome.In 1426 the Pune Guard was formed a group of Pune Warriors founded it to protect the honour of the Church and the Patriarch himself from danger the Pune Guard came to be a symbol of the Patriarchate in Kodingallur.

Flag:

Common Name: The Patriarchate,Kodungallur

Capital: Kodungallur

Head of Government: Patriarch Ittyavirah III

Head of State: Patriarch Ittyavirah III

Demonym: Patriarchal

Languages: 100% Malayalam,40% Marathi,70% Sanskrit (Liturgical language)

Ethnic Groups: 60% Malayali,26% Pune Maratha,5% Other Indian,3% Arab/Persian,1% European

Religions: 70% St.Thomas Christian,15% Hindu,12% Muslim,9% Other Christian

Population: 63,726

Location: Kodungallur

History:

Avraham Yohannan Mathai (Malayalam അവ്രാഹം യോഹന്നാൻ മത്തായി) was born to Thoman a Merchant in Kodungallur and his wife Eliamma in 1289. He became an Ordained priest of the Church of St.Thomas in 1307 at the age of Eighteen where he requested permission from the Archdeacon himself to allow him to spread the word of Jesus Christ throughout India. After gaining permission he journeyed to the court of the King of Pandya Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I where he proselytized the faith of the lord to the local hindus.After numerous battles with the local brahmins he left the Pandya Empire’s borders with many of his converts to Karnataka where he gained many a convert in the region.He then settled in Pune eventually the christian population in Pune outgrew the local hindus.In 1337 Avraham died and was buried in the local Church he was made a saint by the Bishop of Beth Hindaye in 1347 just ten years after his death.In 1350 the local Raja started to persecute the local christians eventually culminating in the Nasrani Rebellion of 1353 and the Pune Christian exodus.The Pune Christians fled in droves down to Kerala where a large amount settled in Kodingallur the city where their saint was born.A Pune Christian by the name of Avaramji Raje Kale-Deshmukh a son of a Kshatriya from Pune who had converted to christianity led an insurrection against the Raja of Kodangillur with the support of the Pune Christian in 1367.After seizing Kodingallur he seized the surrounding cities of Allapuzha and Thiruvananthapuram beginning the Pune Raj and naming himself Chatrappati his successor Chatrappati Yonanaji I Raje Kale-Deshmukh continued his conquests of Kerala with his son Chatrappati Lukasji I Raje Kale-Deshmukh completing the conquest in 1407 with the conquest of Kasaragod.The Pune Raj dynasty gave Kodingallur to the church where the Archdeacon or Jathikkukarthavian of Kodingallur would have complete control over the city.The Arcdeacon of Kodingallur split with the Syriac Church in 1418 when a particularily violent civil war that lasted ten years occured in Assyria which effectively stopped communications between the two churches for sixty years. Jathikkukarthavian Skariah I Simha (The First Marathi Archdeacon) officially split ties with the Syriac Church and established the Patriarchate of Beth Hindaye with himself as the patriarch. The Patriarchs of Kodingallur would for the most part stay at peace and uninteresting acting similarly as to the Popes of Rome.In 1426 the Pune Guard was formed a group of Pune Warriors founded it to protect the honour of the Church and the Patriarch himself from danger the Pune Guard came to be a symbol of the Patriarchate in Kodingallur.

Flag:

Last edited:

((I added arrows in the spots where I added my trading city and my small outposts for convenience. Easily removable with bucket mode, did not alter any extant black dot islands. ))

Official Name: Breton East Indies (BEIC)

Common Name: Breton Asia

Capital: New Brest (Kochi)

Head of Government: His Excellency Guntiern Garandel, Governor-General of the Breton holdings in Asia

Head of State: His Royal Majesty Erispoë III

Demonym: Breton

Languages: 4% Breton, 74% Malayali, 22% various Indian minority languages

Ethnic Groups: 2% Breton, 2% Indo-Breton, 74% Malayali, 22% Indian minority ethnic groups

Religions: 39% Catholic, 60% Buddhist, 1% Jain

Population: (No idea. The population of Kochi and about 5,000 people in Australia)

Location: Kochi, three marked trading posts in Australia

History: The Kingdom of Brittany had never been a powerful nation, be it limited in size and wealth. However, this changed with the colonial era. While Brittany was relatively early in the America's,and colonized relatively heavily there, it arrived in Asia only in the middle of the 1600's. Seeing most favourable locations already occupied by competing powers or long standing ally Aquitaine, the Breton colonial holdings in Asia were kept to an absolute minimum with the intent to only facilitate trade with the East. With a small fleet of cannon bearing ships and a small occupation force, the Bretons forced the Maharadja of Kochi into a protectorate by 1679. This trading city would become surrounded by the AEIC at the end of the 18th century and has become the first of many enclaves in what seems to be becoming Aquitainian India.. While mostly ruling over just the city of Kochi, the Australian trading outposts acquired from Aengland during the 18th century were also placed under the jurisdiction of Kochi. While not the greatest colonial holding, Breton Asia still manages to bring in a pretty penny for the Breton government with the lucrative trade of India it has access to.

Common Name: Breton Asia

Capital: New Brest (Kochi)

Head of Government: His Excellency Guntiern Garandel, Governor-General of the Breton holdings in Asia

Head of State: His Royal Majesty Erispoë III

Demonym: Breton

Languages: 4% Breton, 74% Malayali, 22% various Indian minority languages

Ethnic Groups: 2% Breton, 2% Indo-Breton, 74% Malayali, 22% Indian minority ethnic groups

Religions: 39% Catholic, 60% Buddhist, 1% Jain

Population: (No idea. The population of Kochi and about 5,000 people in Australia)

Location: Kochi, three marked trading posts in Australia

History: The Kingdom of Brittany had never been a powerful nation, be it limited in size and wealth. However, this changed with the colonial era. While Brittany was relatively early in the America's,and colonized relatively heavily there, it arrived in Asia only in the middle of the 1600's. Seeing most favourable locations already occupied by competing powers or long standing ally Aquitaine, the Breton colonial holdings in Asia were kept to an absolute minimum with the intent to only facilitate trade with the East. With a small fleet of cannon bearing ships and a small occupation force, the Bretons forced the Maharadja of Kochi into a protectorate by 1679. This trading city would become surrounded by the AEIC at the end of the 18th century and has become the first of many enclaves in what seems to be becoming Aquitainian India.. While mostly ruling over just the city of Kochi, the Australian trading outposts acquired from Aengland during the 18th century were also placed under the jurisdiction of Kochi. While not the greatest colonial holding, Breton Asia still manages to bring in a pretty penny for the Breton government with the lucrative trade of India it has access to.

Official name: Empire of the Pala (পাল সাম্রাজ্যের)

Unofficially: Bengal (বঙ্গ)

Capital: Pataliputra (পাটলিপুত্র)

Head of State/Government: Maharajadhiraja Jibapala

Demonym: Bengali

Languages: Bengali (83%) Assamese (7%) Other (10%) (Andalusian, other Indo-Aryan languages, Persian, other Arabic dialects, Armenian, Aenglisc, Welsh)

Religion: Hinduism (58%) Mahayana Buddhism (24%) Sunni (10) Other Buddhist schools (7) Other (1%) (Parsi, Nestorian/Thomist, Jewish, Coptic, Cymricist, Catholic) -- The Hindu and Buddhist faiths as practiced here are extremely syncretic and hard to distinguish.

Population: 43 million (This figure includes the population of the areas under de facto Andalusian and Welsh control) [seems enormous… but the EIC Bengal presidency had a pop of 35 mil in 1800, and the Pala Empire, which largely overlaps with presidency, would be even larger.]

Location: Bengal, up the Gangetic plain as far west as Lucknow/Allahabad, Assam

Seal:

Map

Pala claim outlined in green. European claims filled in. It's hard to tell on the map exactly how far inland the Andalusian claim is supposed to go. I'd be more than happy to make further emendations, within reason.

The Pala Empire, in its heydey dominant over most of the eastern Subcontinent, by 1140 had entered into a period of rapid decline. Assam declared independence, Orissa was lost to the Gangas dynasty, corruption was rampant, and the successors of the great Ramapala spent more time plotting to murder their family members than they did governing. By 1160, most of its territory was lost to the Sena dynasty from Karnataka. The Pala had seen low points before, however, and the dynasty had a knack for rebounding in the face of adversity.

Dharmapala II ruled over the smoldering remnants of his dynasty’s land. His branch of the family had largely been excluded from the corridors of power, and Dharmapala had grown up learning to command soldiers during the wars surrounding his family’s decline. A successful military commander, Dharmapala managed to win back Bengal from the Sena. Key to his success was his ability to secure good price for proper Arabian warhorses and his supplementation of his local levies with Turkic mercenaries, from whom he learned a bit about central-Asian military tactics.

In 1175 Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad Ghori, Sultan of the Afghan Ghurid dynasty burst onto the Indian Subcontinent, conquering Multan and Gujarat. Despite fierce resistance from Prithvīrāj Chauhān's Rajput kingdom, and by 1206 Mu’izz ad-Din and his successors had conquered established Muslim rule as far East as Delhi. The fierce warlord Turkic Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji led raids into Pala territory, completely routing a Pala expeditionary force sent to hunt them down. Khilji subsequently looted and razed the great Buddhist Mahavihara Odantapura, brutally slaughtering all the monks, being idol-worshippers who denied Allah after all, who couldn’t flee.

A faithful, if not exactly philosophically astute, Buddhist, Dharmapala II was outraged by the desecration of Odantapura and vowed to defend the holy Buddhist sites remaining in his land, the jewel of which was the great university at Nalanda. Dharmapala II reasoned that a show of strength might at the very least convince Khilji to seek easier pickings elsewhere, and assiduously devoted himself to raising an army with which to defend against the Turks. Having some experience with Turkish tactics, Dharmapala’s generals anticipated the infamous feigned retreat maneuvers of Khilji's army, and despite grievously heavy casualties managed to drive off the Turks, who would subsequently launch an ill-fated attack on Tibet. The realm was thus spared integration into the Sultanate of Delhi. Though Dharmapura’s heirs would lose some territory to their bitter rivals the Sultans, they managed to defend their core territory by learning to ape Muslim tactics, seeking allies where they could find them, and supporting insurrections and factionalism within the Sultanate. They even managed to reclaim land after the Mongols began raiding in the 13th century and finally reassert control over the upstart Assamese. Essentially, having an enormous manpower pool and being just organized enough to make use of it allowed the Palas to survive the onslaught of Muslim conquerors.

The Palas would continue to be great patrons of Buddhist monasteries. The children of the Maharajadhiraja and the ruling family would be educated by monks, learning about the venality of the world and ephemerality of all things, and the importance of the Dasavidha-rājadhamma. Additionally monks would be retained as administrators and advisors throughout the Pala realm, often as tax-collectors, given their supposed incorruptibility. The monks, however, were largely removed from and above the common people, who worshipped the Hindu deities of most of the rest of the subcontinent. In the Pala realms, the two faiths were highly syncretic. Many of the most important landowning rajas were originally Brahmins, but the class hierarchy was not religiously justified and enforced via the caste system. Despite the failure of the Muslim realms to conquer the Pala, Sufi mystics and missionaries had some success converting the local population. Conversion to Islam was especially prominent among the merchant classes, as many of the lands with which they conducted trade were Muslim. Though Muslims have Freedom of worship guaranteed by law, occasionally sometimes they are subject to the vandalization, harassment, and even vigilante violence.

Rich from agricultural production, cloth-waving, and shipbuilding, merchants in cities along the Ganges and its delta maintained trade relationships along the Swahili coast, in Indonesia, and with Tibet. The arrival of Europeans with their swift ships, however, spelt trouble for the Bengali traders. The Andalusians were the most prominent in the area, but Merchants from Europe were attracted to the astounding wealth of Bengali ports in large numbers. The Pala administration was always slightly more suspicious of the Andalusians, being co-religionists with their bitter rivals. The Pala government was unable (and largely unwilling-- this was tacitly a revenue source) to crack down on Piracy against Andalusian traders. Rich Andalusian mercantile interests responded in 1753 by seizing the port of Kalakata (كولكاتا), home to a fair number of Andalusians, sinking the technologically inferior Pala fleet, and routing the army that came to take the city back using advanced artillery techniques. The reigning Rajyapala was currently in the midst of a costly war with their most bitter rivals to the west, the Mongala, and did not have the troops to spare to retake the city. Rajyapala came to an agreement with the Andalusians; in exchange for a portion of port and tax revenue, a guarantee of religious freedom, and freedom of passage for Bengali merchants, the Maharajadhiraja would recognize Andalusian ownership of the seized lands. This strip, though largely consisting of the sundarbans, a swampy tiger-infested jungle, also had some highly productive agricultural land. The local wali ruled these lands with a light touch, granting local landowners enormous privileges over the lower-classes to ensure their loyalty and cooperation. Eager to escape the cruelty of the local landowners, the lower classes fled to the big Andalusian trading city of كولكاتا, which had grown highly large and prosperous through trade. The agreement proved insanely lucrative for the Andalusians; though the Maharajadhiraja was furious about the loss of his lands, but careful Andalusian diplomacy and the share of the cut paid to the Palas proved enough to preserve the status quo. Eager to counter Andalusian influence in the area, and in desperate need of funding for his war with the Mongala, the Maharajadhiraja leased the port of Chittagong to a rival Aenglisc trading company for 50 years in 1768 in exchange for armaments, the freedom of worship and movement agreement, and an enormous lump sum of cash. In the course of the war in 1773, however, the Welsh seized the port from the Aenglisc. The Maharajadhiraja was largely okay with this, provided the Welsh held up the freedom and worship and movement agreement.

Under the continued patronage of the Palas, the great Buddhist university complexes at Nalanda and elsewhere continued to thrive, attracting huge numbers of Burmese, Thai, Tibetan, Chinese, and Japanese visitors, scholars and pilgrims. When Christian missionaries, largely Aenglisc and Aquitanian, arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries, they brought European knowledge of Astronomy and mathematics with them, as well as Western philosophy and theology. This meeting of cultures has led to an intellectual blossoming, a Bengali renaissance, currently in full swing. Nevertheless, the new generation of thinkers has triggered an enormous conservative countermovement as well. The current Maharajadhiraja, Jibapala, is old and clearly suspicious of western influences. His son and heir apparent Ramapala, however, was educated at the monasteries during the height of the renaissance and is more cosmopolitan in outlook.

The Palas enjoy close and mostly peaceful relations with the Burmese and Tibetans, being co-religionists who face religious enemies on their other borders.

Unofficially: Bengal (বঙ্গ)

Capital: Pataliputra (পাটলিপুত্র)

Head of State/Government: Maharajadhiraja Jibapala

Demonym: Bengali

Languages: Bengali (83%) Assamese (7%) Other (10%) (Andalusian, other Indo-Aryan languages, Persian, other Arabic dialects, Armenian, Aenglisc, Welsh)

Religion: Hinduism (58%) Mahayana Buddhism (24%) Sunni (10) Other Buddhist schools (7) Other (1%) (Parsi, Nestorian/Thomist, Jewish, Coptic, Cymricist, Catholic) -- The Hindu and Buddhist faiths as practiced here are extremely syncretic and hard to distinguish.

Population: 43 million (This figure includes the population of the areas under de facto Andalusian and Welsh control) [seems enormous… but the EIC Bengal presidency had a pop of 35 mil in 1800, and the Pala Empire, which largely overlaps with presidency, would be even larger.]

Location: Bengal, up the Gangetic plain as far west as Lucknow/Allahabad, Assam

Seal:

Map

Pala claim outlined in green. European claims filled in. It's hard to tell on the map exactly how far inland the Andalusian claim is supposed to go. I'd be more than happy to make further emendations, within reason.

The Pala Empire, in its heydey dominant over most of the eastern Subcontinent, by 1140 had entered into a period of rapid decline. Assam declared independence, Orissa was lost to the Gangas dynasty, corruption was rampant, and the successors of the great Ramapala spent more time plotting to murder their family members than they did governing. By 1160, most of its territory was lost to the Sena dynasty from Karnataka. The Pala had seen low points before, however, and the dynasty had a knack for rebounding in the face of adversity.

Dharmapala II ruled over the smoldering remnants of his dynasty’s land. His branch of the family had largely been excluded from the corridors of power, and Dharmapala had grown up learning to command soldiers during the wars surrounding his family’s decline. A successful military commander, Dharmapala managed to win back Bengal from the Sena. Key to his success was his ability to secure good price for proper Arabian warhorses and his supplementation of his local levies with Turkic mercenaries, from whom he learned a bit about central-Asian military tactics.

In 1175 Mu'izz ad-Din Muhammad Ghori, Sultan of the Afghan Ghurid dynasty burst onto the Indian Subcontinent, conquering Multan and Gujarat. Despite fierce resistance from Prithvīrāj Chauhān's Rajput kingdom, and by 1206 Mu’izz ad-Din and his successors had conquered established Muslim rule as far East as Delhi. The fierce warlord Turkic Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji led raids into Pala territory, completely routing a Pala expeditionary force sent to hunt them down. Khilji subsequently looted and razed the great Buddhist Mahavihara Odantapura, brutally slaughtering all the monks, being idol-worshippers who denied Allah after all, who couldn’t flee.

A faithful, if not exactly philosophically astute, Buddhist, Dharmapala II was outraged by the desecration of Odantapura and vowed to defend the holy Buddhist sites remaining in his land, the jewel of which was the great university at Nalanda. Dharmapala II reasoned that a show of strength might at the very least convince Khilji to seek easier pickings elsewhere, and assiduously devoted himself to raising an army with which to defend against the Turks. Having some experience with Turkish tactics, Dharmapala’s generals anticipated the infamous feigned retreat maneuvers of Khilji's army, and despite grievously heavy casualties managed to drive off the Turks, who would subsequently launch an ill-fated attack on Tibet. The realm was thus spared integration into the Sultanate of Delhi. Though Dharmapura’s heirs would lose some territory to their bitter rivals the Sultans, they managed to defend their core territory by learning to ape Muslim tactics, seeking allies where they could find them, and supporting insurrections and factionalism within the Sultanate. They even managed to reclaim land after the Mongols began raiding in the 13th century and finally reassert control over the upstart Assamese. Essentially, having an enormous manpower pool and being just organized enough to make use of it allowed the Palas to survive the onslaught of Muslim conquerors.

The Palas would continue to be great patrons of Buddhist monasteries. The children of the Maharajadhiraja and the ruling family would be educated by monks, learning about the venality of the world and ephemerality of all things, and the importance of the Dasavidha-rājadhamma. Additionally monks would be retained as administrators and advisors throughout the Pala realm, often as tax-collectors, given their supposed incorruptibility. The monks, however, were largely removed from and above the common people, who worshipped the Hindu deities of most of the rest of the subcontinent. In the Pala realms, the two faiths were highly syncretic. Many of the most important landowning rajas were originally Brahmins, but the class hierarchy was not religiously justified and enforced via the caste system. Despite the failure of the Muslim realms to conquer the Pala, Sufi mystics and missionaries had some success converting the local population. Conversion to Islam was especially prominent among the merchant classes, as many of the lands with which they conducted trade were Muslim. Though Muslims have Freedom of worship guaranteed by law, occasionally sometimes they are subject to the vandalization, harassment, and even vigilante violence.

Rich from agricultural production, cloth-waving, and shipbuilding, merchants in cities along the Ganges and its delta maintained trade relationships along the Swahili coast, in Indonesia, and with Tibet. The arrival of Europeans with their swift ships, however, spelt trouble for the Bengali traders. The Andalusians were the most prominent in the area, but Merchants from Europe were attracted to the astounding wealth of Bengali ports in large numbers. The Pala administration was always slightly more suspicious of the Andalusians, being co-religionists with their bitter rivals. The Pala government was unable (and largely unwilling-- this was tacitly a revenue source) to crack down on Piracy against Andalusian traders. Rich Andalusian mercantile interests responded in 1753 by seizing the port of Kalakata (كولكاتا), home to a fair number of Andalusians, sinking the technologically inferior Pala fleet, and routing the army that came to take the city back using advanced artillery techniques. The reigning Rajyapala was currently in the midst of a costly war with their most bitter rivals to the west, the Mongala, and did not have the troops to spare to retake the city. Rajyapala came to an agreement with the Andalusians; in exchange for a portion of port and tax revenue, a guarantee of religious freedom, and freedom of passage for Bengali merchants, the Maharajadhiraja would recognize Andalusian ownership of the seized lands. This strip, though largely consisting of the sundarbans, a swampy tiger-infested jungle, also had some highly productive agricultural land. The local wali ruled these lands with a light touch, granting local landowners enormous privileges over the lower-classes to ensure their loyalty and cooperation. Eager to escape the cruelty of the local landowners, the lower classes fled to the big Andalusian trading city of كولكاتا, which had grown highly large and prosperous through trade. The agreement proved insanely lucrative for the Andalusians; though the Maharajadhiraja was furious about the loss of his lands, but careful Andalusian diplomacy and the share of the cut paid to the Palas proved enough to preserve the status quo. Eager to counter Andalusian influence in the area, and in desperate need of funding for his war with the Mongala, the Maharajadhiraja leased the port of Chittagong to a rival Aenglisc trading company for 50 years in 1768 in exchange for armaments, the freedom of worship and movement agreement, and an enormous lump sum of cash. In the course of the war in 1773, however, the Welsh seized the port from the Aenglisc. The Maharajadhiraja was largely okay with this, provided the Welsh held up the freedom and worship and movement agreement.

Under the continued patronage of the Palas, the great Buddhist university complexes at Nalanda and elsewhere continued to thrive, attracting huge numbers of Burmese, Thai, Tibetan, Chinese, and Japanese visitors, scholars and pilgrims. When Christian missionaries, largely Aenglisc and Aquitanian, arrived in the 17th and 18th centuries, they brought European knowledge of Astronomy and mathematics with them, as well as Western philosophy and theology. This meeting of cultures has led to an intellectual blossoming, a Bengali renaissance, currently in full swing. Nevertheless, the new generation of thinkers has triggered an enormous conservative countermovement as well. The current Maharajadhiraja, Jibapala, is old and clearly suspicious of western influences. His son and heir apparent Ramapala, however, was educated at the monasteries during the height of the renaissance and is more cosmopolitan in outlook.

The Palas enjoy close and mostly peaceful relations with the Burmese and Tibetans, being co-religionists who face religious enemies on their other borders.

Last edited:

Official Name: Pune-Marathi Empire

Common Name: Maratha Empire,Pune Empire

Capital: Ālāppujhā (Allapuzha)

Head of Government: Chhatrapati Bajirao Avrahamji Raje Kale-Deshmukha IV

Head of State: Chhatrapati Bajirao Avrahamji Raje Kale-Deshmukha IV

Demonym: Marathi

Languages: 30% Marathi (Official Language of Administration),30% Malayali,7% European

Languages,10% Arabic, 40% Kannada

Ethnic Groups: 30% Kannada,20% Malayali,10% Pune Marathi,4% Tamil,7% Other Indians,3% Europeans

Religions: 36% St Thomas Christianity,38% Hindu,10% Other Christian,10% Sunni,3% Shia,2% Parsi,1% Jain

Population: 5 Million

Location: Kerala

History: