Oh Mary .. such a tragic tale . Especially with that new Elizabeth movie coming out , ugh , double hurt . I can only look forward to the next installment with dread .

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Just finished reading through JM! Great stuff, especially all the information on the Kingdom at the beginning, I may have to grab some of those ideas of you

Lets hope Elizabeths succession will at the very least be beneficial to the nation! Maybe the Catholics and Protestants can sort things out together? Though I doubt not..

Great stuff JM I look forward to the next update!

Lets hope Elizabeths succession will at the very least be beneficial to the nation! Maybe the Catholics and Protestants can sort things out together? Though I doubt not..

Great stuff JM I look forward to the next update!

canonized: Dread indeed... dread indeed. That's all I can say right now.

stnylan: Of course, she's got more troubling her "glorious" reputation in this story than in real life; I'll get to that in due time...

RGB: Well, a bit of head-chopping, but very little. That'll come soon enough, including what was in real life the only English king to end his reign shorter than he began.

Olaus Petrus: Real-life Mary doesn't really deserve to be called "Bloody Mary", but that's how it is sometimes. She's even gentler in this version, so she almost ends up not being bloody at all.

English Patriot: Oooh, nice to see you show up all of a sudden. Don't take too much from my original information, as much of it is altered to fit the changes that occured during the CK section of the megacampaign. As for the two denominations sorting things out together... well, no. Just, no.

Don't take too much from my original information, as much of it is altered to fit the changes that occured during the CK section of the megacampaign. As for the two denominations sorting things out together... well, no. Just, no.

And no Woodhouses of note in this version of England, but that's how it is sometimes...

stnylan: Of course, she's got more troubling her "glorious" reputation in this story than in real life; I'll get to that in due time...

RGB: Well, a bit of head-chopping, but very little. That'll come soon enough, including what was in real life the only English king to end his reign shorter than he began.

Olaus Petrus: Real-life Mary doesn't really deserve to be called "Bloody Mary", but that's how it is sometimes. She's even gentler in this version, so she almost ends up not being bloody at all.

English Patriot: Oooh, nice to see you show up all of a sudden.

And no Woodhouses of note in this version of England, but that's how it is sometimes...

Judas Maccabeus said:English Patriot: Oooh, nice to see you show up all of a sudden.Don't take too much from my original information, as much of it is altered to fit the changes that occured during the CK section of the megacampaign. As for the two denominations sorting things out together... well, no. Just, no.

And no Woodhouses of note in this version of England, but that's how it is sometimes...

I've been neglecting reading AAR's for way too long, its only really since Canonized "introduced" me to AARland that I'm finally in the mindset, so I'm trying to make up for lost time!

Oh don't worry, I may just grab a few ideas, the racial groups of the Empire for one thing, I can't believe I never thought of that

As for the religious problems - Oh well, I suppose thats England for you,

And no Woodhouse's of note? Ah well, Kings in one, and nowhere to be seen in another, I suppose its the trade off for me embracing Norman culture

Tragic tales and religious turmoil in the home isles. Will Elizabeth be able to manouvre herself through this political and religious minefield?

English Patriot: I might consider adding "Woodhouse" to the random leader names, along with some other more Saxon names... and use whatever you want, I'm sure you'll be able to pick whatever fits best.

TeeWee: I don't think there's any room to maneuver at the moment, at least not long-term. In order to keep one group from causing trouble, one must necessarily anger a different group...

Update later today, once I finish the battle for it.

TeeWee: I don't think there's any room to maneuver at the moment, at least not long-term. In order to keep one group from causing trouble, one must necessarily anger a different group...

Update later today, once I finish the battle for it.

Judas Maccabeus said:English Patriot: I might consider adding "Woodhouse" to the random leader names, along with some other more Saxon names... and use whatever you want, I'm sure you'll be able to pick whatever fits best.

Thanks

Looking forward to the update

[English Patriot: I typed it up in Notepad, then used when putting it in here. That's not my work, though, I borrowed the format from a different website.  ]

]

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Queen of England, Scotland, Ireland [and France]

Lady of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duchess of Buckingham, Holland and Friesland [to 1566], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Countess of Stafford

Elisabeth did not even arrive in England until July of 1559, leaving her official husband behind. Fortunately, most of the nobility were more concerned with waiting to see what this new ruler would be like, and less with trying to cause too much trouble while she was gone; most figured that a woman would be easy enough to control anyway. What happened when she did arrive would cause considerable trouble for the entire nation, both on the islands themselves and with the Continent.

Her first decree upon returning to her native country was to rescind Mary's reunification of the Church of England with the Catholic Church. A new Act of Supremacy was created and enacted on 2 July 1559, not long before Elisabeth returned. Elisabeth was no longer one to go halfway; her ill treatement by Mary, along with encouragement by both her late stepmother Salome and German merchants in Novgorod, had driven her well into the arms of Protestantism. She realised that a religiously divided England would not be ultimately stable, and thus set about removing Catholics wherever possible.

It was a long-term goal which had some immediate problems. The Catholic portions of the country, as would be expected, did not react to this well. The most immediate rebellion occured in Yorkshire, but was a haphazard effort that was easily dealt with by August. The second rebellion, however, would be far larger and more organised; more importantly, it occured in Holland, where English control was somewhat weaker.

Surprisingly, Holland did not get swept along in Protestantism, despite the growing merchant middle class (where Protestant thought most often took root). The causes for this are uncertain; the religious and artistic traditions of the 15th century may have had something to do with it, along with trading connections to the Italians and Spanish. Whatever the cause, the Dutch reacted with fervour to Elisabeth's declaration, drawing upon both religious belief and a nascent feeling of Dutch nationalism. The first stage of the Dutch War of Independence began in early 1560, with a demand for a convention of the General Estates of Holland and Friesland. Elisabeth, realising exactly what the Dutch had in mind - forced recognition of Catholicism there - refused and prepared the army to cross the Channel.

The Surrender of Breda, by Diego Velazquez (1635)

The commander, Sir Phillip Osbourne, had an easy enough job swatting away the small group attempting to take Brugge. By March, he was already marching north into Zeeland, expecting the rest of the fight to be just as easy. After quickly ensuring the submission of Breda, Osbourne marched north to cross the Lower Rhine at Vianen, hoping from there to take Utrecht and thus a central position from which to control the rest of Holland.

Along the way, however, he ran across the Dutch at the village of Giessenlanden. His army, still collecting itself along the road, numbered nearly 33,000 men, and the Dutch had less than half that number - later estimates put it at approximately 15,000. However, the Dutch had two major advantages: their system of dikes and canals provided them with a natural defensive system, and they had collected all the available cannon, 20 according to the most reliable sources, purchased from Italian craftsmen eager to aid their fellow Catholics, and most likely paid for by Philip II of Spain.

Osbourne quickly formulated a plan and put it into action immediately, not giving the Dutch a chance to be used to the English presence there. His army was not entirely rested, but still quite capable of giving battle, and he felt that a sudden, concentrated force would be able to break the line and disperse the "rabble". With this, he sent about half of his army across the Kleine Vliet ("little stream") on the Dutch right flank. En masse the English rushed forward, the front infantry taking heavy losses but not breaking. Finally, as the army reached within 50 yards of the stream, Osbourne pulled out the main part of the attacK: The infantry opened lanes up, and 4,000 heavy cavalry, to this point hidden by the tall pikes of the infantry, came forward at full gallop to jump across the stream. Osbourne, a devoted chess player, was using a "revealed attack", hoping to surprise the Dutch line completely.

It should have worked, but didn't. The ground was soggy, the cavalry began slowing, and a dozen guns now fired upon the same spot, while the Dutch copied the English in effective use of longbows. Only around 500 of the cavalry got across, all of whom were quickly cut down. Of the rest, only 600 managed to make it back. It was an attack which would be combined with Agincourt and the later "Charge of the Light Brigade" in the annals of futile cavalry charges. Meanwhile, the rest of the infantry was failing to make much more progress, and a general panic siezed that part of the army.

Osbourne, meanwhile, had a second trick in play. The rest of the army, coming across another stream at Giessenlanden itself, had been marching north to join the attack as a second wave. However, this was a trick to draw off the second line of the Dutch in that direction. It appeared to work, as the English suddenly switched direction and moved in full charge to the Dutch left flank. Unfortunately for Osbourne, the complete collapse of the other attack allowed the Dutch to move all of the second line to the left instead, and the attackers completely lost heart. Most didn't even get within the effective range of the cannon, electing instead to go in the other direction. The English army had recieved a crushing blow, Osbourne choosing to go back to Breda to reform his army, now 10,000 men smaller.

The Battle of Giessenlanden. Each line is c. 1000 men.

It took considerable work for him to retain command, but retain it he did. He was now determined to strike back, and by July his army came back north. This time, he used native Protestant spies to great effect, bypassing the Dutch army completely and forcing it to fight on his own terms on 14 July. The Dutch were dispersed with only minimal English losses, and Utrecht quickly retaken. The English suffered a close defeat again near the fishing village of Amsterdam on 30 August, but by 18 November they entered Haarlem and apparently ended the revolt.

It would again be not quite so easy, however. In January of 1561, while Osbourne was with a detachment pacifying Friesland, the people of Haarlem rose up and took the city. Incensed, he had to rush back, resulting in another defeat on 9 March. While trying to pull his army back to Utrecht, it was again ambushed on 18 April, forcing him back against the Lower Rhine. It looked bad, but Osbourne was determined to succeed. On 7 July, he badly outmaneuvered the Dutch rebels near at Doorn, allowing him to move towards Haarlem.

Soon after he reached the city, however, the Dutch finally put up a united front against Elisabeth. On 1 October 1561, Willem van Gulik, the Count of Geldre, met with the Stadtholder of Haarlem, Willem van Oranje, in Arnhem. The latter Willem had been a Catholic appointed by Mary, but with some Protestant leanings. Elisabeth didn't care much about leanings, however, and forced him out of his position. The Count put his support behind him as the leader of a Dutch union. At this news, the rest of the Netherlands soon announced their support; Osbourne first learned of this when a new flag appeared over the city of Haarlem, smuggled in from outside: Orange-white-blue, the colours of the new United Provinces. With his supply lines in tatters, Osbourne quickly pulled back to Antwerp in order to ensure the loyalty of the major ports of Flanders. Brugge itself was in revolt, and was not retaken until 24 September 1562, at which point Osbourne prepared to attack.

The fight began well. Elisabeth called upon the King of Baden and the Count of Oldenburg to support her, and both responded; Oldenburg was especially important, as it opened a second front in the north. Unfortuantely, the Dutch had a large force to put against both flanks, and after initial victories in the Brabant region, Osbourne was forced into a close battle outside Gent on 7 February 1563. Both sides had around 25,000 men, with the English using more cavalry; the determined Dutch, however, refused to break, and Osbourne was forced to leave the field in disgrace. On 26 April, Brugge fell, threating to force England out of the Low Countries entirely.

Osbourne did not give up, however. Amidst howls in Parliament calling for his removal, and by the end of the year he had smashed the southern Dutch armies, retaking Flanders and threatening Brussels. At the same time, a large English army arrived in Oldenburg, placed under the command of that city's Count, and began marching into Friesland. The Dutch were unable to counter both threats at once, and it appeared as if the Catholic rebellion might be destroyed. Over the next year, both Friesland and Brabant were solidly secured, and in 1564 Osbourne easily took Zeeland and southern Holland. His goal now was not to quickly smash the rebel armies, but to secure each area before moving on. It was becoming quite effective, and by 23 July 1565 he was threatening Haarlem itself.

Before the rebellion could be completely destroyed, however, problems appeared elsewhere. The people of Boston had remained defiantly Catholic, and revolted at the same time as other Catholics revolted in Ireland and Kent. On 30 August 1566, the Kent rebels reached the southern suburbs of London, and only a quick defence by Anglican militia saved the capital. Haarlem itself did not fall until 7 October, with Dutch armies still at large. Osbourne could not remain; he sacked the city, pulled back, and finally set forth an armistice which split the country in two. England retained Flanders, most of Brabant, and Liege, while the Dutch kept everything to the north. It was the best that could be done in the long term, and Osbourne knew the political reality. It would eventually cost him his career, but he felt it an acceptable sacrifice; "Iy reue it not," he later wrote, "þat iy eþelly þoud Engeland beforan myself."

Sir Phillip Osbourne, by Steven van der Muelen (c. 1565)*

Ironically, the immediate reason for the Dutch revolt - their Catholicism - soon became a moot point. Calvinism had slowly been taking root amongst the Dutch, and within a decade of independence most of the country was Protestant. It was too late for the English, however: the war had long since become one of proto-nationalism, with the Dutch moving away from English forms and choosing to assert themselves as a separate people. Although relations with the new Dutch Republic would vastly improve over the next century, English control of the region was limited to the south.

__________

*Actually a portrait of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, but since he isn't important in this story I'm using it for someone who actually was important.

Elisabeth I the Virgin

Born: 7 September 1533, London

Married: Nikita Zakharyin (on 11 August 1557)

Died: 25 March 1603, London

Born: 7 September 1533, London

Married: Nikita Zakharyin (on 11 August 1557)

Died: 25 March 1603, London

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Queen of England, Scotland, Ireland [and France]

Lady of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duchess of Buckingham, Holland and Friesland [to 1566], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland and Bretagne]

Countess of Stafford

"No wild beasts are so dangerous to men as Christians are to one another."

--Julian the Apostate

Elisabeth did not even arrive in England until July of 1559, leaving her official husband behind. Fortunately, most of the nobility were more concerned with waiting to see what this new ruler would be like, and less with trying to cause too much trouble while she was gone; most figured that a woman would be easy enough to control anyway. What happened when she did arrive would cause considerable trouble for the entire nation, both on the islands themselves and with the Continent.

Her first decree upon returning to her native country was to rescind Mary's reunification of the Church of England with the Catholic Church. A new Act of Supremacy was created and enacted on 2 July 1559, not long before Elisabeth returned. Elisabeth was no longer one to go halfway; her ill treatement by Mary, along with encouragement by both her late stepmother Salome and German merchants in Novgorod, had driven her well into the arms of Protestantism. She realised that a religiously divided England would not be ultimately stable, and thus set about removing Catholics wherever possible.

It was a long-term goal which had some immediate problems. The Catholic portions of the country, as would be expected, did not react to this well. The most immediate rebellion occured in Yorkshire, but was a haphazard effort that was easily dealt with by August. The second rebellion, however, would be far larger and more organised; more importantly, it occured in Holland, where English control was somewhat weaker.

Surprisingly, Holland did not get swept along in Protestantism, despite the growing merchant middle class (where Protestant thought most often took root). The causes for this are uncertain; the religious and artistic traditions of the 15th century may have had something to do with it, along with trading connections to the Italians and Spanish. Whatever the cause, the Dutch reacted with fervour to Elisabeth's declaration, drawing upon both religious belief and a nascent feeling of Dutch nationalism. The first stage of the Dutch War of Independence began in early 1560, with a demand for a convention of the General Estates of Holland and Friesland. Elisabeth, realising exactly what the Dutch had in mind - forced recognition of Catholicism there - refused and prepared the army to cross the Channel.

The Surrender of Breda, by Diego Velazquez (1635)

The commander, Sir Phillip Osbourne, had an easy enough job swatting away the small group attempting to take Brugge. By March, he was already marching north into Zeeland, expecting the rest of the fight to be just as easy. After quickly ensuring the submission of Breda, Osbourne marched north to cross the Lower Rhine at Vianen, hoping from there to take Utrecht and thus a central position from which to control the rest of Holland.

Along the way, however, he ran across the Dutch at the village of Giessenlanden. His army, still collecting itself along the road, numbered nearly 33,000 men, and the Dutch had less than half that number - later estimates put it at approximately 15,000. However, the Dutch had two major advantages: their system of dikes and canals provided them with a natural defensive system, and they had collected all the available cannon, 20 according to the most reliable sources, purchased from Italian craftsmen eager to aid their fellow Catholics, and most likely paid for by Philip II of Spain.

Osbourne quickly formulated a plan and put it into action immediately, not giving the Dutch a chance to be used to the English presence there. His army was not entirely rested, but still quite capable of giving battle, and he felt that a sudden, concentrated force would be able to break the line and disperse the "rabble". With this, he sent about half of his army across the Kleine Vliet ("little stream") on the Dutch right flank. En masse the English rushed forward, the front infantry taking heavy losses but not breaking. Finally, as the army reached within 50 yards of the stream, Osbourne pulled out the main part of the attacK: The infantry opened lanes up, and 4,000 heavy cavalry, to this point hidden by the tall pikes of the infantry, came forward at full gallop to jump across the stream. Osbourne, a devoted chess player, was using a "revealed attack", hoping to surprise the Dutch line completely.

It should have worked, but didn't. The ground was soggy, the cavalry began slowing, and a dozen guns now fired upon the same spot, while the Dutch copied the English in effective use of longbows. Only around 500 of the cavalry got across, all of whom were quickly cut down. Of the rest, only 600 managed to make it back. It was an attack which would be combined with Agincourt and the later "Charge of the Light Brigade" in the annals of futile cavalry charges. Meanwhile, the rest of the infantry was failing to make much more progress, and a general panic siezed that part of the army.

Osbourne, meanwhile, had a second trick in play. The rest of the army, coming across another stream at Giessenlanden itself, had been marching north to join the attack as a second wave. However, this was a trick to draw off the second line of the Dutch in that direction. It appeared to work, as the English suddenly switched direction and moved in full charge to the Dutch left flank. Unfortunately for Osbourne, the complete collapse of the other attack allowed the Dutch to move all of the second line to the left instead, and the attackers completely lost heart. Most didn't even get within the effective range of the cannon, electing instead to go in the other direction. The English army had recieved a crushing blow, Osbourne choosing to go back to Breda to reform his army, now 10,000 men smaller.

The Battle of Giessenlanden. Each line is c. 1000 men.

It took considerable work for him to retain command, but retain it he did. He was now determined to strike back, and by July his army came back north. This time, he used native Protestant spies to great effect, bypassing the Dutch army completely and forcing it to fight on his own terms on 14 July. The Dutch were dispersed with only minimal English losses, and Utrecht quickly retaken. The English suffered a close defeat again near the fishing village of Amsterdam on 30 August, but by 18 November they entered Haarlem and apparently ended the revolt.

It would again be not quite so easy, however. In January of 1561, while Osbourne was with a detachment pacifying Friesland, the people of Haarlem rose up and took the city. Incensed, he had to rush back, resulting in another defeat on 9 March. While trying to pull his army back to Utrecht, it was again ambushed on 18 April, forcing him back against the Lower Rhine. It looked bad, but Osbourne was determined to succeed. On 7 July, he badly outmaneuvered the Dutch rebels near at Doorn, allowing him to move towards Haarlem.

Soon after he reached the city, however, the Dutch finally put up a united front against Elisabeth. On 1 October 1561, Willem van Gulik, the Count of Geldre, met with the Stadtholder of Haarlem, Willem van Oranje, in Arnhem. The latter Willem had been a Catholic appointed by Mary, but with some Protestant leanings. Elisabeth didn't care much about leanings, however, and forced him out of his position. The Count put his support behind him as the leader of a Dutch union. At this news, the rest of the Netherlands soon announced their support; Osbourne first learned of this when a new flag appeared over the city of Haarlem, smuggled in from outside: Orange-white-blue, the colours of the new United Provinces. With his supply lines in tatters, Osbourne quickly pulled back to Antwerp in order to ensure the loyalty of the major ports of Flanders. Brugge itself was in revolt, and was not retaken until 24 September 1562, at which point Osbourne prepared to attack.

The fight began well. Elisabeth called upon the King of Baden and the Count of Oldenburg to support her, and both responded; Oldenburg was especially important, as it opened a second front in the north. Unfortuantely, the Dutch had a large force to put against both flanks, and after initial victories in the Brabant region, Osbourne was forced into a close battle outside Gent on 7 February 1563. Both sides had around 25,000 men, with the English using more cavalry; the determined Dutch, however, refused to break, and Osbourne was forced to leave the field in disgrace. On 26 April, Brugge fell, threating to force England out of the Low Countries entirely.

Osbourne did not give up, however. Amidst howls in Parliament calling for his removal, and by the end of the year he had smashed the southern Dutch armies, retaking Flanders and threatening Brussels. At the same time, a large English army arrived in Oldenburg, placed under the command of that city's Count, and began marching into Friesland. The Dutch were unable to counter both threats at once, and it appeared as if the Catholic rebellion might be destroyed. Over the next year, both Friesland and Brabant were solidly secured, and in 1564 Osbourne easily took Zeeland and southern Holland. His goal now was not to quickly smash the rebel armies, but to secure each area before moving on. It was becoming quite effective, and by 23 July 1565 he was threatening Haarlem itself.

Before the rebellion could be completely destroyed, however, problems appeared elsewhere. The people of Boston had remained defiantly Catholic, and revolted at the same time as other Catholics revolted in Ireland and Kent. On 30 August 1566, the Kent rebels reached the southern suburbs of London, and only a quick defence by Anglican militia saved the capital. Haarlem itself did not fall until 7 October, with Dutch armies still at large. Osbourne could not remain; he sacked the city, pulled back, and finally set forth an armistice which split the country in two. England retained Flanders, most of Brabant, and Liege, while the Dutch kept everything to the north. It was the best that could be done in the long term, and Osbourne knew the political reality. It would eventually cost him his career, but he felt it an acceptable sacrifice; "Iy reue it not," he later wrote, "þat iy eþelly þoud Engeland beforan myself."

Sir Phillip Osbourne, by Steven van der Muelen (c. 1565)*

Ironically, the immediate reason for the Dutch revolt - their Catholicism - soon became a moot point. Calvinism had slowly been taking root amongst the Dutch, and within a decade of independence most of the country was Protestant. It was too late for the English, however: the war had long since become one of proto-nationalism, with the Dutch moving away from English forms and choosing to assert themselves as a separate people. Although relations with the new Dutch Republic would vastly improve over the next century, English control of the region was limited to the south.

__________

*Actually a portrait of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, but since he isn't important in this story I'm using it for someone who actually was important.

Despite Elizabeth's measures religious disagreements are still breaking out, and the loss of Holland, not the best start in the world, but lets hope she salvages something!

Marvellous update JM

Marvellous update JM

It will be interesting to see what the equivalent of the Elizabethan church settlement is in this timeline. Also, I bet Phillip regretted supprting the revolt, creating a Calvinist trading power.

I see that long history of you getting your ass kicked in the continent continues. Losing the rich Dutch provinces was a major setback for England.

Wow. The United Provinces have proven themselves a very tough nut to crack, even though they had some good luck with a revolt in the home isles. The Spanish King will probably kick himself in the head as well, setting up a heretic rich state, threatening European trade.

I love the way you turned the religious revolt turns into a nationalistic revolt. It mirrors how revolts often change in their nature and cause. Good update!

I love the way you turned the religious revolt turns into a nationalistic revolt. It mirrors how revolts often change in their nature and cause. Good update!

canonized: And believe me, it only gets worse.

English Patriot: I don't see the religious disagreements going away anytime soon... the religious situation in England is far more poisonous than in real life.

LeonTrotsky: That'll be a major part of the next update, along with other various trends in Bess' reign. And you can't really blame Phillip, he couldn't have known...

Olaus Petrus: Yeah, England isn't good at projecting power over the sea at this point, but fortunately it works both ways.

RGB: Thank God for small miracles, I suppose.

Wait, should a Catholic like me be saying that when a Protestant country keeps land?

TeeWee: Again, Phillip was doing the right thing at the time. The Netherlands won't actually be as rich as in real life, thanks to being more devoted to trade with England and less with North Germany up to this point, causing trouble now that said trade is disrupted.

The historical Dutch revolt itself changed some during its 80-year span. And, as you know well, the Hussite rebellion was never entirely static in its goals and methods.

I should have the 1569 [half]-Century Report up soon, and after that a look at the Reformation to this point.

English Patriot: I don't see the religious disagreements going away anytime soon... the religious situation in England is far more poisonous than in real life.

LeonTrotsky: That'll be a major part of the next update, along with other various trends in Bess' reign. And you can't really blame Phillip, he couldn't have known...

Olaus Petrus: Yeah, England isn't good at projecting power over the sea at this point, but fortunately it works both ways.

RGB: Thank God for small miracles, I suppose.

Wait, should a Catholic like me be saying that when a Protestant country keeps land?

TeeWee: Again, Phillip was doing the right thing at the time. The Netherlands won't actually be as rich as in real life, thanks to being more devoted to trade with England and less with North Germany up to this point, causing trouble now that said trade is disrupted.

The historical Dutch revolt itself changed some during its 80-year span. And, as you know well, the Hussite rebellion was never entirely static in its goals and methods.

I should have the 1569 [half]-Century Report up soon, and after that a look at the Reformation to this point.

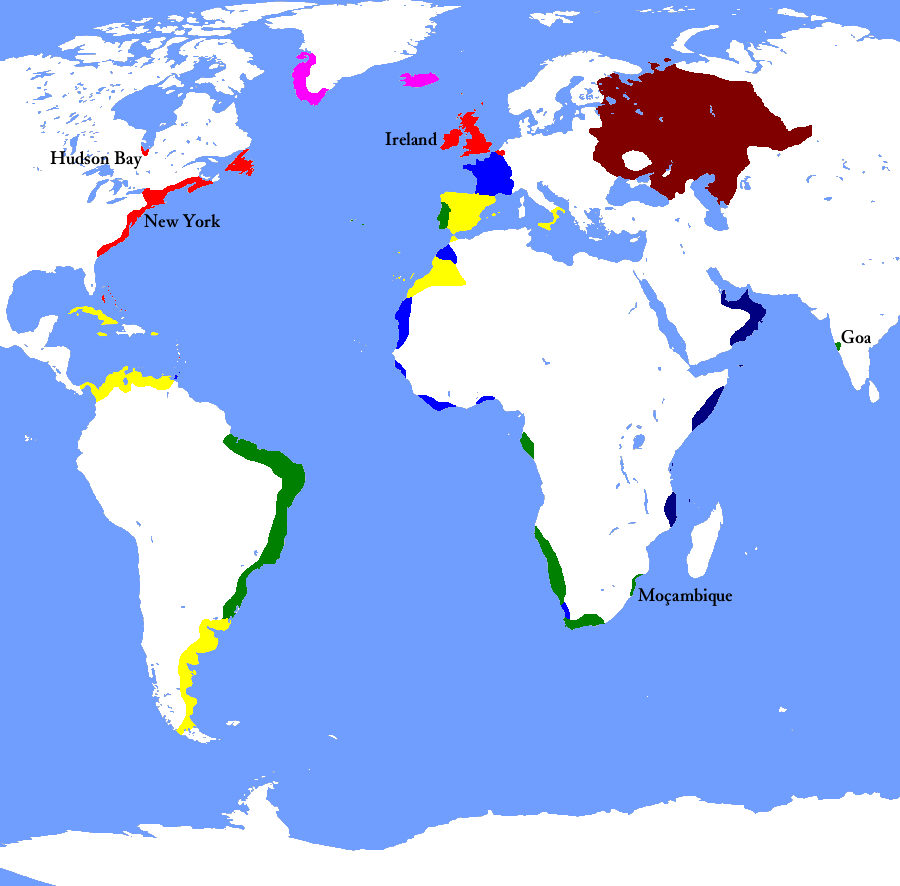

[HALF]-CENTURY REPORT: 1569

Europe

(click for large map)

The first notable change is that Finnland has overrun the Danish lands in Scandinavia itself. That country has quickly become the most important in the area, easily dominating the two around it, and is in a very strong alliance with Russia. The country has entered a small golden age, both in external affairs and internally.

Another major event is the union of Poland and Lithuania. They have been in personal union for more than a century, but only in this year has it been made official at the Polish capital of Lublin. This union is a response to potential agression both from Russia to the east and the Babenburgs to the south.

Said Babenburgs themselves have pushed back the Turks in Hungary, conquering the principality of Transylvania and reaching the Danube near Belgrade. Other expansion has been in Bavaria (in concert, oddly enough, with the Protestant countries of Baden and the Palatinate) and against Venice.

An Egyptian campaign has smashed the power of the Qarakhnids, but the invasion lost impetus before highly-fortified and hilly Jerusalem could be taken. The Holy City, however, is surrounded and only exists at Egypt's sufferance. Since Christians now are allowed free access to the city, a final campaign is not quite imminent.

Russia has also been slowly increasing its power to the south, taking lands from the Ukrainians and Azerbaijan.

Central Europe

In Germany itself, little politically has changed in the intervening time period. Only three changes have occured to borders: Bavaria has been greatly reduced, Pommerania has lost eastern lands to the Poles, and the Dutch have gained their independence from England.

Much has changed in religious matters, but that will be dealt with later.

In Italy, on the other hand, several countries have seized the collapse of the centralised state to take land for themselves. The Dukes of Milan have found themselves a tributary of a very powerful Siena, the Genovese have taken all of the important Italian islands, and the Dukes of Romagna - whose ambition began this anarchy - have gained control of much of the central part of the peninsula.

The Pope has been reduced to an area around Rome itself, bringing to mind ill memories of earlier conquest by the Kings of Italy.

In the south, Spain has inherited Sicily, and with it the southern reaches of Italy. Any hope of northward expansion, however, is checked by a powerful Romagna and a less-than-friendly Genoa.

Colonies

Russian expansion into Siberia continues at a slow pace, pushing to find a border with China and the ocean in that direction.

American colonisation has mostly been concerned with expansion in areas already taken, with the English connecting the northern and southern parts of their lands, while the Spanish have been working on their colony of La Plata. The English have also gained a colony of sorts near their own lands, with the retaking of Ireland.

The Portuguese have begun European influence in India, setting up a trading port in Goa. To support this, they have set up a small presence on the African coast in Mozambique.

Wow JM very cool maps ! Any possibility for a religious map in the future perhaps ?