English Patriot: Yep, I'm working to have English slowly settle into a "modern" form. It'll still sound quite archaic and Germanic to our ears, of course, but that's what happens with 200 more years of Saxon rule.

TeeWee: Well, she's going to be busy with other matters, as you are about to find out.

I'm feeling quite inspired this weekend. I'll finish up Lizzie, and then take a rest for a week before we start the next ruler.

- - - - - - - -

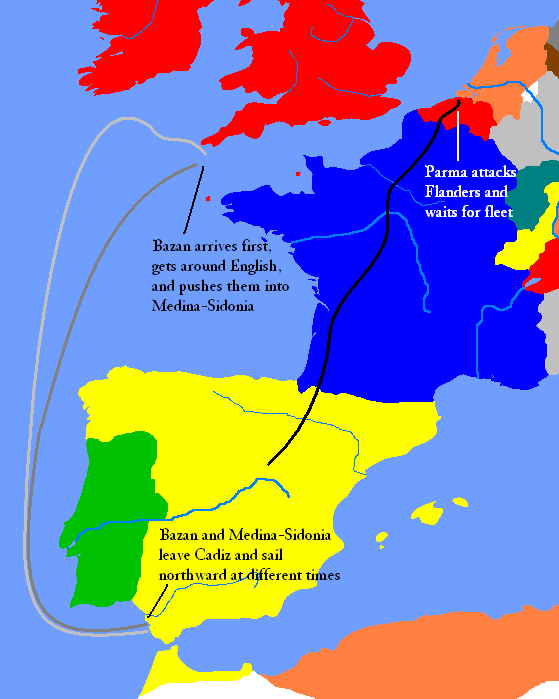

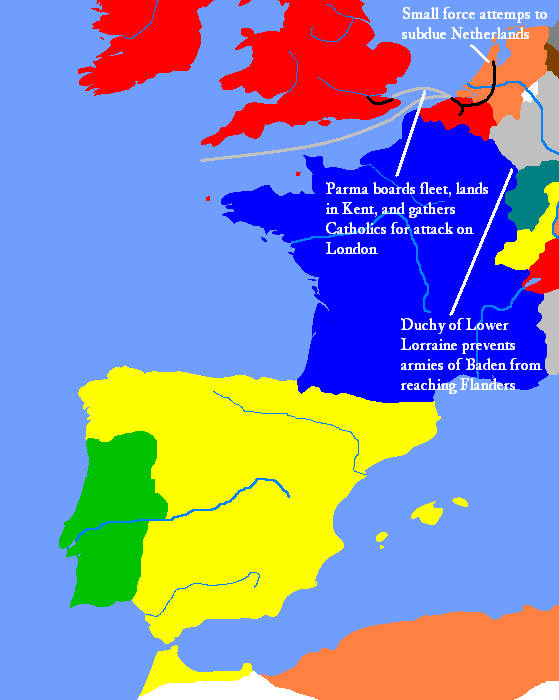

Peace with Spain did not end conflict, however. The Catholic inhabitants of the country, having risen up in rebellion, would not go down quite as easily, and the later part of 1589 marked the beginning of a renewed civil war. Lancashire, the Scottish highlands, and Kent flared up in rebellion all around the same time; an army sent from Edinburgh (led by the new Duke of Lothian, James) ran up across an approximately equal number of Catholics near Inverness and was sent back southward. He would return late in February of 1590, having reformed his army, to crush them in a bloody battle.

Meanwhile, the Kentish Catholics again besieged London. The army had been drawn north to deal with the Lancastrian Catholics, and was out of place when the Kentish surged northward. The army arrived in time, however, defeated the army, and then set to besieging Canterbury. The city surrendered on 12 September 1590, expecing to be treated well because they had not forced an assault.

They were wrong. As soon as the army came into the city, they set upon the inhabitants of the city with incredible fervor. Much of the army was composed of a more radical group, the Puritans, and they could not allow a "Papist" presence in the country; within minutes, they attacked anyone who seemed even the slightest bit Catholic. Thousands were killed, churches destroyed, and the body of St. Thomas Becket taken from the cathedral, burned, and thrown into the sea.

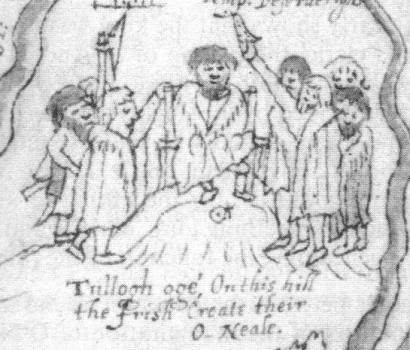

This had as shocking an effect on Catholics as the massacare in Blois had had on Protestants. The Spanish fleet was still in no condition to attempt an attack on England, and France was too busy with their own Protestants; but there were enough in England itself to at least try and do the job. Ireland flared up in complete and total rebellion, led by the Earl of Tyrone, Hugh O'Neill. At his side was Red Hugh O'Donnell, the Lord of Tyrconnel, who was the true military genius of the rebellion.*

Hugh being declared head of the O'Neill clan, from a 1600 map.

One Catholic nation did go to fight the English: the Holy Roman Emperor, Ernst von der Ardennen. In response, Elisabeth claimed that Luxemburg was a part of the English Netherlands, and brought Baden and the Dutch in to help. The war went well; at Stolberg on 5 May 1592, an 22,000-strong English army under the Earl of Leicester easily defeated nearly 35,000 Imperial soldiers. With the Dutch adding 25,000 men and the Badeners 30,000 to the campaign, the English were able to sweep through the country, and on 20 June 1593, the Treaty of Malmedy granted the region of Luxemburg to Elisabeth. Within a few years, Ernst's realm would collapse, as Protestant nobles in the northern regions rebelled against him and gained their independence.

With that outside Catholic threat destroyed, Elisabeth was able to focus on the Irish. Tyrconnel defeated an English army sent against him in Connacht in April of 1592, but an allied force was destroyed in Leinster that June. He was able to reach as far as Belfast on 26 November, and the English army in Ireland was hemmed in, but Scottish reinforcements made their way across, and Ulster was retaken by late May. The rebellion would continue on a low scale through the rest of Elisabeth's reign, going back and forth for more than a decade.

Elisabeth's anti-Catholic policies did succeed in making headway against some regions. The Catholic regions of Northumberland and Lancaster slowly became more Protestant, as did the Scottish highlands; Catholics remained, but by the late 1590s they no longer made a majority of the populace, and rebellions found less and less support. Conversions in America at this time focused on the natives; the governor of Virginia, John Smith, led a campaign in the Wyandot lands in 1600 which forced the leaders of that tribe to convert and accept Elisabeth's sovreignity.

The most famous person to find some difficulty due to Elisabeth's policy was a playwright from the Avon valley, William Shakespeare. Several times he was accused of Papism; the question of whether these accusations are true or not (he could never admit it openly) is still unanswered. Despite this, however, his fame and ability caused his group to gain the patronage of the Lord Chamberlain, and, after Elisabeth's death, her own heir as the Emperor's Men.

Elsewhere, one man sought to continue Francis Drake's attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Henry Hudson, a London sailor, was contracted in 1597 by the Pacific Company to try and find a route to India. He set off from London, then proceeding to New Albion. From there, he travelled across the Pacific; on 28 June 1599, he reached (and named) New Zealand and on 26 December passed through the Hudson Straits.** By the middle of 1600 he had reached Fort Buckingham on Magriban Island.*** From there, it was a simple matter, resupplying at Portuguese ports along the African coast, to make it back to London in 1601. He was met by massive crowds as his

Half Moon docked along the Thames, and in a ceremony soon after was knighted for his achievement as the first man to circumnavigate the globe.

Sir Henry Hudson, in a late 19th century depiction (no contemporary one exists).

The final matter of Elisabeth's reign was her succession. The common claim of her virginity is a difficult one to confirm or deny; her absolute hatred for her husband Nikita Romanovich Zakharyin made a lack of consummation there possible, but rumors abound of affairs with any number of courtiers in England. In any case, she never remarried after Zakharyin's death in 1586; several suitors came forward, but she rejected all for political reasons. Finally, she simply named her not-so-distant relative James, the Duke of Lothian, as her heir. He was immediately accepted by the nobility of England.

In January of 1603, in anticipation of James' inheritance, Parliament passed the Act of Union. This united the crowns of England and Scotland, along with their parliaments; the new land was to be called the Empire of Great Britain. The use of an Imperial dignity was an ambitious one, but the various Protestant powers all accepted its use.† Elisabeth's new title was:

"ELISABEÞ, þrough Godes Gift Empresse of GREATBRITEN; Cween of Iraland & Francland; Ladiy of þe Scottisc & of þe Crecisc Iyles; Ducesse of Bucingham, of Holland & of Friesland, of þe Flanders, of Cornwall, of Island, & of Bretonland; & Countesse of Stafford; of þe Circ in Greatbriten & in Iraland Supreme Head & Defendresse of þe Faiþe; for þe Ceeping of þe hwilc abid we to Crist Iesu, to hwam haþ been gifen Rice & Doom ofer alle þe lands of þe Earþ, and wiþ out hwam ney Mann may wield."

Allegorical depiction of an aged Elisabeth, 1610s.

By early 1603, Elisabeth's health had completely failed. Her problems did not appear to be from any outside source, but she grew weaker and weaker, especially mentally; by 21 March she was bedridden, and on 24 March she died. The Privy Council immediately declared James Borcalan to be the new Emperor, calling him down from Edinburgh to take his place on the throne, ending the Stafford period and beginning the Borcalan dynasty.

__________

*The Cornish also went into revolt, but were quickly put down.

**In our timeline, the Strait of Torres.

***Reunion.

† The Russian response was somewhat more complex. They claimed the Imperial dignity for themselves through the Byzantine Empire, and didn't like others using it; eventually, Peter the Great of Russia made its use for England official during his reforms.