WOW! That was just great!!  Great ethnic informations, you are describing your alternative history setup with very suggestive and realistic way

Great ethnic informations, you are describing your alternative history setup with very suggestive and realistic way

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Great looking map after conversion. Interesting to see that French capital is Orléans instead of Paris.

And background information was interesting and good to read, like always.

And background information was interesting and good to read, like always.

thrasing mad: I just hope the continuation of the alternate history is just as good.

Kurt_Steiner: Why thank you.

Olaus Petrus: Blois, actually. The de Blois dynasty usurped the throne from the Capets in the 1100s, and never actually took Paris--that fell under the authority of the Dukes of Valois--until just a few years before game start. Paris is still very important, however.

- - - - - - - -

Several nations have come to dominate their portions of Europe, although in most cases their position is tenuous. England controls most of Northwest Europe, stable for now but in conflict with a powerful France and with varying levels of control over the outlying parts of the empire.

France itself is stable but must contend with a hostile England, and its main avenues for expansion, over the Pyrenees and the Rhine, would open up some rather nasty hornets' nests.

Hammadid control over their part of Northern Africa is quite secure, but the Muslim possessions of Spain have collapsed into several states threatened by an allied Castilla and Aragon. A concerted effort by the two should easily restore Christian rule to the peninsula.

Italy is somewhat strong, but racked with instability, and with much of its proper lands in the hands of others it must go at things slowly and not anger too many people at once.

The Kalmar Union in the north is less of an official reality and more Denmark trying to push around practically controled Sweden and Norway. Finland remains defiantly independent between two large powers.

Russia is a large state, but backwards and in control of some sparsely-settled land. The two main thorns in its side are the Polish-Lithuanian alliance (no more than an alliance) and a Catholic Ukraine. Azerbaijan and Russia are for the moment content to say on their own sides of the Caucasus.

The Abesanids are a Turkish group with several easy pickings on their borders. Once those are used up, however, they must attack strong nations such as Hungary or Azerbaijan to expand their influence. Furthermore, they intend to defend the unnatural and weak Muslim state of Croatia from foreign encroachment, which will divert some of their resources.

Egypt has Catholicized most of its land, but expansion will likely prove rather difficult. The most obvious route would be to conquer the Qarakhnids, an option well within the realm of possiblity, but likely a slow and difficult one. That, and the Abesanids will expand in the meantime...

Persia is a technical successor to the old Seljuk Turks, but they are not themselves Turkish or have rulers directly descended from the Seljuks. They are powerful, but other powerful nations will rapidly arrive on their borders.

The Holy Roman Empire, 1419

The Holy Roman Empire has ceased to exist as a proper political entity, although the Emperor--currently Dietrich von Zaehringen in the region of Baden--has some authority. Said authority is still in rapid decline, however, and the states of the Empire have already secured the right to elect a new Emperor upon the current one's death.

The weak nature of the many Imperial states would appear to make it vulnerable to attack. Their sheer number, however, means that anyone who appears would immediately find themselves beset by a swarm of by no means defenceless states. Austria, Bohemia, and Brandenburg protect the east; Baden and Helvetia the south; the County Palatine and Cologne the west, and the Hanseatic League of Bremen, Holstein, Mecklenburg, and Pommerania the north. Even past this, strong states such as Saxony and Bavaria prevent any easy pickings in the hearland of the Empire.

Elsewhere, the "Babylonian captivity" of the Papacy in France continues, while Friesland and Geldre must consider their position in a Netherlands dominated by England and France.

Iberia in 1419

A Hammadid attack in the 1300s destroyed the southern kingdom of Leon and nearly did in Castilla. However, they--along with the independent states of the coastline--managed to hold off their enemy and now are prepared to strike back. Asturias' "migration" from one end of Spain to another has finally settled in the middle, while a Muslim Portugal will soon be overthrown by Christians looking outward. The question of what is to be done once the Re-Reconquista is finished is an important one, and already some have begun to plan expeditions around Africa to contact India.

Greece in 1419

The states of the old Byzantine Empire have collapsed into an odd mixture of religions and cultures. Pagan Greeks hold sway in Epiros (incorrectly marked "Albania" on this map); Catholic Greeks hold Morea and Crete while the English have Cyprus and Rhodes; Muslim Arabs are in Zeta and Dulkadir while the Turks control large areas in the middle, the lands of the Abesanids and Arzrounis.

The Abesanid Empire is a recent collection of the Turkish states of the region under the control of one family, who have had authority over the region around Constantinople for two centuries. With the rest of the Turks (except those in Arzrouni) by their side, they now intend expansion for the sake of Islam and themselves.

Religion in 1419

The qualified success of the Crusades and the resulting chaos in southeastern Europe has left pockets of several religions within each other, most notably the Catholics of Egypt, the Muslims of Croatia, and even Greek Pagans in Epiros. Many successes by all the religions involved are rather tenuous, especially the Muslims in Iberia, the Pagans everywhere, the Catholics in Greece and the Ukraine, and the Orthodox in the Turkish lands.

Even when the religion of the rulers is taken out some interesting developments have occured. Catholics remain in Tangeirs and Tunis despite the loss of Christian rule over those places long since. Although the Byzantine Empire has been destroyed, much of the population still professes the Orthodox faith, a situation which the Turks have done little to discourage. Hungarian Serbia also remains Orthodox.

Most notably, and not representable on this map, is that heretical groups such as the Lollards and the Hussites have already appeared in England and Bohemia, respectively (along with minor movements in Savoy and Lithuania), and while their influence at this time (especially for the Lollards) are limited, Catholic Europe will in a century be in for a major shock...

Kurt_Steiner: Why thank you.

Olaus Petrus: Blois, actually. The de Blois dynasty usurped the throne from the Capets in the 1100s, and never actually took Paris--that fell under the authority of the Dukes of Valois--until just a few years before game start. Paris is still very important, however.

- - - - - - - -

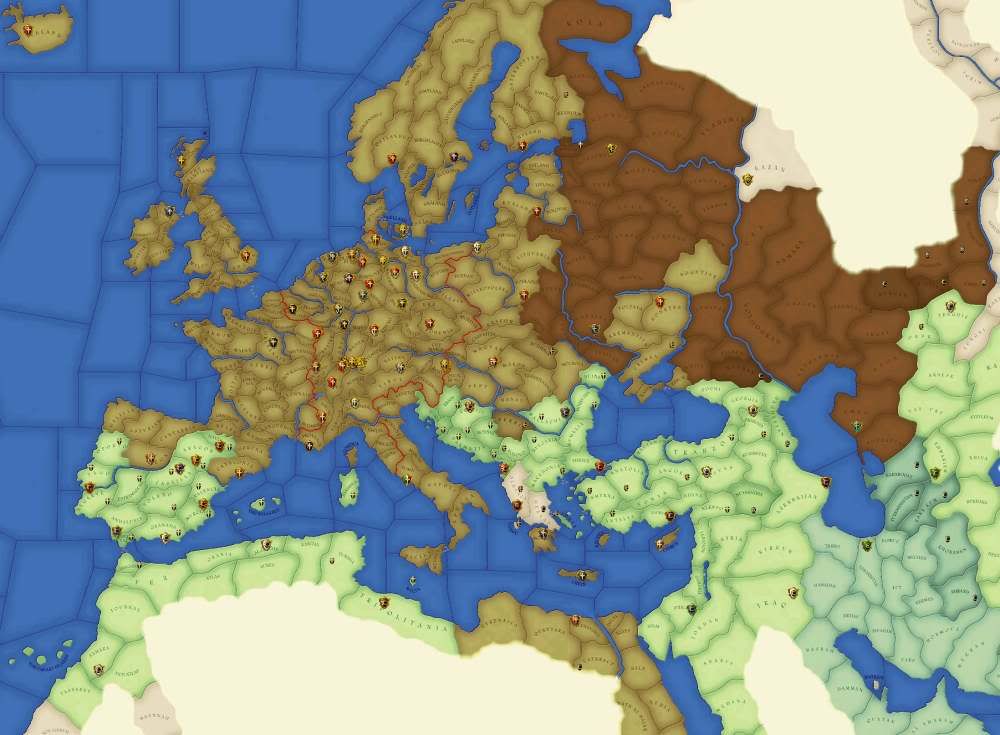

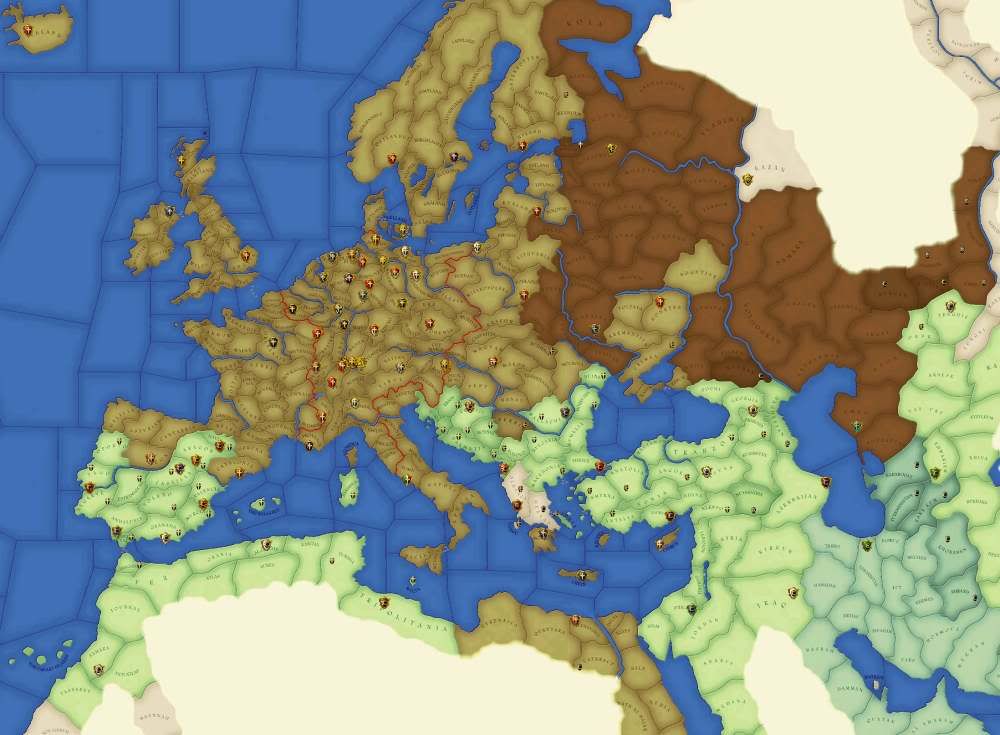

Europe in 1419

Europe, 1419

This is the small version--the full one is 4415 by 3307 pixels. At 72 DPI that would be a map 1.56 m by 1.17 m, which is obviously big. I wish I had a physical map of this Europe that big.

Currently in union (vassalizations) are Russia and Kiev; England, Ireland, Scotland, Iceland, and Cyprus; and Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

Europe, 1419

This is the small version--the full one is 4415 by 3307 pixels. At 72 DPI that would be a map 1.56 m by 1.17 m, which is obviously big. I wish I had a physical map of this Europe that big.

Currently in union (vassalizations) are Russia and Kiev; England, Ireland, Scotland, Iceland, and Cyprus; and Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

Several nations have come to dominate their portions of Europe, although in most cases their position is tenuous. England controls most of Northwest Europe, stable for now but in conflict with a powerful France and with varying levels of control over the outlying parts of the empire.

France itself is stable but must contend with a hostile England, and its main avenues for expansion, over the Pyrenees and the Rhine, would open up some rather nasty hornets' nests.

Hammadid control over their part of Northern Africa is quite secure, but the Muslim possessions of Spain have collapsed into several states threatened by an allied Castilla and Aragon. A concerted effort by the two should easily restore Christian rule to the peninsula.

Italy is somewhat strong, but racked with instability, and with much of its proper lands in the hands of others it must go at things slowly and not anger too many people at once.

The Kalmar Union in the north is less of an official reality and more Denmark trying to push around practically controled Sweden and Norway. Finland remains defiantly independent between two large powers.

Russia is a large state, but backwards and in control of some sparsely-settled land. The two main thorns in its side are the Polish-Lithuanian alliance (no more than an alliance) and a Catholic Ukraine. Azerbaijan and Russia are for the moment content to say on their own sides of the Caucasus.

The Abesanids are a Turkish group with several easy pickings on their borders. Once those are used up, however, they must attack strong nations such as Hungary or Azerbaijan to expand their influence. Furthermore, they intend to defend the unnatural and weak Muslim state of Croatia from foreign encroachment, which will divert some of their resources.

Egypt has Catholicized most of its land, but expansion will likely prove rather difficult. The most obvious route would be to conquer the Qarakhnids, an option well within the realm of possiblity, but likely a slow and difficult one. That, and the Abesanids will expand in the meantime...

Persia is a technical successor to the old Seljuk Turks, but they are not themselves Turkish or have rulers directly descended from the Seljuks. They are powerful, but other powerful nations will rapidly arrive on their borders.

The Holy Roman Empire, 1419

The Holy Roman Empire has ceased to exist as a proper political entity, although the Emperor--currently Dietrich von Zaehringen in the region of Baden--has some authority. Said authority is still in rapid decline, however, and the states of the Empire have already secured the right to elect a new Emperor upon the current one's death.

The weak nature of the many Imperial states would appear to make it vulnerable to attack. Their sheer number, however, means that anyone who appears would immediately find themselves beset by a swarm of by no means defenceless states. Austria, Bohemia, and Brandenburg protect the east; Baden and Helvetia the south; the County Palatine and Cologne the west, and the Hanseatic League of Bremen, Holstein, Mecklenburg, and Pommerania the north. Even past this, strong states such as Saxony and Bavaria prevent any easy pickings in the hearland of the Empire.

Elsewhere, the "Babylonian captivity" of the Papacy in France continues, while Friesland and Geldre must consider their position in a Netherlands dominated by England and France.

Iberia in 1419

A Hammadid attack in the 1300s destroyed the southern kingdom of Leon and nearly did in Castilla. However, they--along with the independent states of the coastline--managed to hold off their enemy and now are prepared to strike back. Asturias' "migration" from one end of Spain to another has finally settled in the middle, while a Muslim Portugal will soon be overthrown by Christians looking outward. The question of what is to be done once the Re-Reconquista is finished is an important one, and already some have begun to plan expeditions around Africa to contact India.

Greece in 1419

The states of the old Byzantine Empire have collapsed into an odd mixture of religions and cultures. Pagan Greeks hold sway in Epiros (incorrectly marked "Albania" on this map); Catholic Greeks hold Morea and Crete while the English have Cyprus and Rhodes; Muslim Arabs are in Zeta and Dulkadir while the Turks control large areas in the middle, the lands of the Abesanids and Arzrounis.

The Abesanid Empire is a recent collection of the Turkish states of the region under the control of one family, who have had authority over the region around Constantinople for two centuries. With the rest of the Turks (except those in Arzrouni) by their side, they now intend expansion for the sake of Islam and themselves.

Religion in 1419

The qualified success of the Crusades and the resulting chaos in southeastern Europe has left pockets of several religions within each other, most notably the Catholics of Egypt, the Muslims of Croatia, and even Greek Pagans in Epiros. Many successes by all the religions involved are rather tenuous, especially the Muslims in Iberia, the Pagans everywhere, the Catholics in Greece and the Ukraine, and the Orthodox in the Turkish lands.

Even when the religion of the rulers is taken out some interesting developments have occured. Catholics remain in Tangeirs and Tunis despite the loss of Christian rule over those places long since. Although the Byzantine Empire has been destroyed, much of the population still professes the Orthodox faith, a situation which the Turks have done little to discourage. Hungarian Serbia also remains Orthodox.

Most notably, and not representable on this map, is that heretical groups such as the Lollards and the Hussites have already appeared in England and Bohemia, respectively (along with minor movements in Savoy and Lithuania), and while their influence at this time (especially for the Lollards) are limited, Catholic Europe will in a century be in for a major shock...

*sigh*... It's while making that update that I realized that there's so many interesting stories in this history aside from the English one, that I can't do them all justice. I'd love to do something about the Princes of Pereyeslavl becoming Kings of Russia, or the Norman unification of Italy and the troubled reign of Fausto the Kinslayer, or Egypt, the crusader state that lost its crusader status and has provided a stable Arab Catholic tradition, or the rise of the Abesanid dynasty from a minor vassal to the Seljuks to the leaders of ane empire, or Finland's roller-coaster ride from small group of pagan tribes to the conquerers of all Scandinavia and much else besides, to destruction, to rebirth as an independent Christian duchy...

I could go on, there's so much.

I could go on, there's so much.

It's interesting how much more Celtic this kingdom is becoming, considering both it's anglosaxon origins and its history in our time as more frankified. That's the beauty of CK, the whole thing is so interesting (when it's not completely ridiculous).

Situation in Europe is certainly interesting. I hope that Finland can survive between Russia and Scandinavians and grow to great power once more.

JimboIX: I made sure that the craziest CK stuff didn't happen or wasn't allowed to get through the transfer. Now for the crazy EU2 stuff to begin...

Kurt_Steiner: Again, thank you.

Olaus Petrus: Sorry, but I imagine the original Finnish Empire was a bit of a fluke. It would be nice, but...

The first gameplay update will come later today or tomorrow. Finally!

Kurt_Steiner: Again, thank you.

Olaus Petrus: Sorry, but I imagine the original Finnish Empire was a bit of a fluke. It would be nice, but...

The first gameplay update will come later today or tomorrow. Finally!

Just a question... couldn't be a way to make Catalonia bigger while expelling the Moors and subduing Castille and the rest of the Peninsula at the same time?

While Catalonia is till independent, I should add.

While Catalonia is till independent, I should add.

Very fascinating AAR so far, i would love to hear all the different stories you described! please, more

-Maximilliano

-Maximilliano

Kurt_Steiner: Not without me playing as Aragon. Actually, probably not even with me playing as Aragon, I'm not that good at this game even after over five years...

Maximilliano: The rest of Europe will only be described intermittently, but I'll try to fit it in there when I can.

- - - - - - - -

[NOTE: Until recently, this AAR referred to this king by his given Welsh name, and the one he used, Maelgwn. As his English name, Malcolm, fits better with the rulers around him, however, it has been changed.]

Titles:

King of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish and Greek Isles

Duke of Holland, Bretagne, Normandy, Poitou, and Iceland

Count of Guines and Navarra

Regent of France and Heir to the French Throne (from 1420)

Malcolm wished to attack France immediately, but a short and abortive rebellion by the Earl of Bedford--who was replaced with his brother Iorweth--forced him to wait until the beginning of the year. Malcolm's French strategy revolved around several points: First, England would attack with over 40,000 men immediately (30,000 in Normandy and over 10,000 in Poitou), with another 20,000 in England preparing to cross the channel and add a second wave of fresh soldiers. John d'Audley, the Duke of Moray, would lead the Scottish contingent of at least 25,000 more, while Henry de Windsor, Duke of Connacht, led 30,000 Irish. To further add to Malcolm's numbers, he signed an alliance with the Count of Geldre, gaining another 12,000 men.

Serlo had died a few years before and his heir was Asclettin, by no means anywhere near the ability of his father. Asclettin was given to bouts of insanity; once, at a ball, he danced covered in pitch, and nearly caught fire and burned to death as a result. In any case, he was hardly fit to lead an army, and without anyone else of note they had only their numbers to rely upon--around 60,000 men--and even that only until the rest of the English armies came. They would have to overcome the English immediately.

Asclettin the Mad (or Beloved), from a contemporary manuscript.

Malcolm began marching forward just after the new year. He himself led around 15,000 into Picardy, in order to link up the English possessions of Normandy and Guines; another 15,000 under the new Duke of Bedford moved towards the French capital of Blois, where they were aided by the one turncoat in the French ranks: Malcolm's distant relatives, the de Cornouaille Dukes of Orleans. The Duke of Gloucester's 15,000 in Poitou moved first to Limousin, but then north towards the Loire to intercept a French column attempting to reinforce the northern armies. The Count of Geldre moved into Zeeland to protect Holland.

The results were mixed. Gloucester easily swept aside the column he was intercepting and Bedford soon had Blois under siege, after defeating an army 20,000 strong. However, Maelgwn was surprised by 10,000 French, and simply broke through to Calais to reconsider his strategy. That same 10,000 then moved into Zeeland and swept aside the Count of Geldre, threating Holland.

Maelgwn's strategic situation was still fairly good. With the help of Geldre, he attacked Flandern, forcing the French in Holland to pull back only to be surrounded by the Dutch and eliminated. Unfortunately, in March an even larger French army from the south, commanded by Constable Richard de Valois, struck while the Dutch were away and nearly overwhelmed Malcolm's smaller army. He again pulled back to Calais and collected several thousand reinforcements from England.

He pushed forward again in July. Bedford had recently captured Blois and was moving on to Maine, distracting some of the French attention. Malcolm pushed the French out of Flanders and then began maneuvering to cut them off. With only 10,000 effective men by late July (with the other 15,000 from England not expected to arrive until August), this seemed like a foolish idea--but Malcolm had a place in mind to tear the French army to pieces.

He managed to move the French into this place on 28 July 1419 (the feast of Samson of York, as celebrated in Shakespeare's account). It was a depression in the ground between the villages of Agincourt (or Azincourt) and Tramecourt, with very dense woods on the flanks. The effective strengths of both sides are not certain, but the general consensus is around 8,000 for the English and 25,000 for the French, an approximately 3-1 advantage for the latter.* Malcolm set his army up between the forests, with a line of sharpened stakes in front of his archers.

The French formed three lines of battle, intending to punch through with the first line and destroy them with the second, the third being merely in reserve because there was nowhere to put them. As the first line advanced, the second paused for a bit before coming in behind it. Then, the arrows began to fly: all of Malcolm's longbowmen began sending their deadly ammunition across the field, often using ballistics to cause two arrows to strike at once (shooting one on a high, slow arc to get around the horses' head armor and a second on a fast, shallow arc to punch through any weak spot in the French armor).

The second line panicked and thought that those in front of them needed help, adding to another quirk of the battlefield: the open space began to narrow as it neared the English position, forcing the French to bunch up. The mass was an unmissable target, and as they struck the English line they soon found that they were unable to use their weapons effectively. Even the lightly armed longbowmen had an advantage over the packed mass, and the French began to surrender en masse. A few thousand of the second wave made their way out while the third line never even budged except to leave the battlefield at the end.

The Battle of Agincourt. Each line is c. 1,000 men.

That would have been the end, except that a thousand French peasants had shown up and began to loot the English baggage train while they were distracted. Malcolm, thinking this a French sneak attack, ordered the execution of his prisoners before they could fall into enemy hands. Obviously, this was not a popular move, but it was carried out. Rather than 6,000 captured, the death toll was now 7,000 dead. Malcolm had lost only a few hundred (certainly less than a thousand), and would soon have 15,000 more at his side.

The French war now turned upside-down. Malcolm pushed towards Paris and had it under siege by mid-August. He began negotiating with Jean, Duke of Burgundy, a negotiation that began to create good fruits. However, the "Dauphin" (heir to the French throne), Etienne II, also invited him to a negotiation at Montereu. It was a trap: The duke and his bodyguard were set upon and killed, and the duke's heir, Phillip III, got the message. England would have no help from that end. Worse, France began negotiating with the kings of Castilla and Aragon to lend their aid once they could get peace with the Moors.

Still, things continued well. Malcolm captured Paris on 17 February 1420, and managed to convince Asclettin to sign a humiliating agreement that made Malcolm his heir (stating that Etienne was illegitimate, a charge that very well may have been true considering the reputation of Asclettin's wife). While France was technically out of the war, Etienne continued fighting from his power base in the southern part of the country. Malcolm also married Asclettin's daughter Catherine, to replace his first wife, who had recently died and had not given him a son.

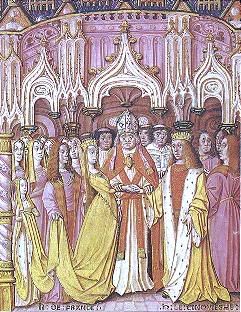

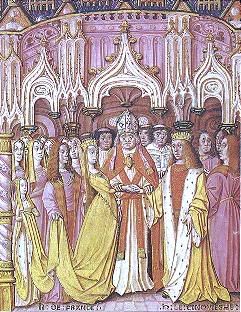

The wedding of Maelgwn and Catherine de Blois.

This was when things began to turn. Malcolm's expedition into Nivernais was met by Etienne's army, with the Spanish now beginning to show in force. Scottish and Irish reinforcements were not enough to turn the tide, and Malcolm began to pull back. Fighting soon focused on the region around Blois. The battle went back and forth well into 1421, and in a series of battles the French finally managed to regain the city. Malcolm managed to get another large force (now near the limits of his money and manpower) and begin besieging the city again, but when another expedition into Nivernais failed in July 1422, both Maelgwn and Etienne agreed that there needed to be a rest. The English gained Picardy and the region around Paris, along with a restatement of the earlier agreement, given the official title of the Treaty of Troyes.

Malcolm would not be able to enjoy the fruits of his apparent victory. Having contracted dysentery in the fighting, he took ill and, on 31 August 1422, died. He had only his young son (less than a year old) Ioan II to survive him as king. Had Malcolm survived, he could have accepted at least an offical inheritance two months later with Asclettin's death.

__________

*Other estimates range from making the French advantage only 2-1 (10,000 to 20,000) to an astounding and almost certainly false 6-1 (6,000 to 36,000).

Maximilliano: The rest of Europe will only be described intermittently, but I'll try to fit it in there when I can.

- - - - - - - -

[NOTE: Until recently, this AAR referred to this king by his given Welsh name, and the one he used, Maelgwn. As his English name, Malcolm, fits better with the rulers around him, however, it has been changed.]

Malcolm (Maelgwn)

"Maelcoluim IV" of Scotland

Born: 13 July 1396, Reading

Married: [1] Blodwen ap Cynddelw (on 6 August 1412)

[2] Catherine de Blois (on 2 June 1420)

Died: 31 August 1422, Vincennes, France

"Maelcoluim IV" of Scotland

Born: 13 July 1396, Reading

Married: [1] Blodwen ap Cynddelw (on 6 August 1412)

[2] Catherine de Blois (on 2 June 1420)

Died: 31 August 1422, Vincennes, France

Titles:

King of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish and Greek Isles

Duke of Holland, Bretagne, Normandy, Poitou, and Iceland

Count of Guines and Navarra

Regent of France and Heir to the French Throne (from 1420)

Of [Dieneces the Spartan] there is a saying recorded, one that he uttered before the battle was joined: whe he heard a Malian saying that, when the barbarians shot their arrows, the very sun was darkened by their multitude, so great was the number of them, Dieneces was not a whit abashed, but in his contempt for the numbers of the Medes said, "Why, my Trachinian friend brings us good news. For if the Medes hide the sun, we shall fight them in the shade."

--Herodotus, History, 7.226

Malcolm wished to attack France immediately, but a short and abortive rebellion by the Earl of Bedford--who was replaced with his brother Iorweth--forced him to wait until the beginning of the year. Malcolm's French strategy revolved around several points: First, England would attack with over 40,000 men immediately (30,000 in Normandy and over 10,000 in Poitou), with another 20,000 in England preparing to cross the channel and add a second wave of fresh soldiers. John d'Audley, the Duke of Moray, would lead the Scottish contingent of at least 25,000 more, while Henry de Windsor, Duke of Connacht, led 30,000 Irish. To further add to Malcolm's numbers, he signed an alliance with the Count of Geldre, gaining another 12,000 men.

Serlo had died a few years before and his heir was Asclettin, by no means anywhere near the ability of his father. Asclettin was given to bouts of insanity; once, at a ball, he danced covered in pitch, and nearly caught fire and burned to death as a result. In any case, he was hardly fit to lead an army, and without anyone else of note they had only their numbers to rely upon--around 60,000 men--and even that only until the rest of the English armies came. They would have to overcome the English immediately.

Asclettin the Mad (or Beloved), from a contemporary manuscript.

Malcolm began marching forward just after the new year. He himself led around 15,000 into Picardy, in order to link up the English possessions of Normandy and Guines; another 15,000 under the new Duke of Bedford moved towards the French capital of Blois, where they were aided by the one turncoat in the French ranks: Malcolm's distant relatives, the de Cornouaille Dukes of Orleans. The Duke of Gloucester's 15,000 in Poitou moved first to Limousin, but then north towards the Loire to intercept a French column attempting to reinforce the northern armies. The Count of Geldre moved into Zeeland to protect Holland.

The results were mixed. Gloucester easily swept aside the column he was intercepting and Bedford soon had Blois under siege, after defeating an army 20,000 strong. However, Maelgwn was surprised by 10,000 French, and simply broke through to Calais to reconsider his strategy. That same 10,000 then moved into Zeeland and swept aside the Count of Geldre, threating Holland.

Maelgwn's strategic situation was still fairly good. With the help of Geldre, he attacked Flandern, forcing the French in Holland to pull back only to be surrounded by the Dutch and eliminated. Unfortunately, in March an even larger French army from the south, commanded by Constable Richard de Valois, struck while the Dutch were away and nearly overwhelmed Malcolm's smaller army. He again pulled back to Calais and collected several thousand reinforcements from England.

He pushed forward again in July. Bedford had recently captured Blois and was moving on to Maine, distracting some of the French attention. Malcolm pushed the French out of Flanders and then began maneuvering to cut them off. With only 10,000 effective men by late July (with the other 15,000 from England not expected to arrive until August), this seemed like a foolish idea--but Malcolm had a place in mind to tear the French army to pieces.

He managed to move the French into this place on 28 July 1419 (the feast of Samson of York, as celebrated in Shakespeare's account). It was a depression in the ground between the villages of Agincourt (or Azincourt) and Tramecourt, with very dense woods on the flanks. The effective strengths of both sides are not certain, but the general consensus is around 8,000 for the English and 25,000 for the French, an approximately 3-1 advantage for the latter.* Malcolm set his army up between the forests, with a line of sharpened stakes in front of his archers.

The French formed three lines of battle, intending to punch through with the first line and destroy them with the second, the third being merely in reserve because there was nowhere to put them. As the first line advanced, the second paused for a bit before coming in behind it. Then, the arrows began to fly: all of Malcolm's longbowmen began sending their deadly ammunition across the field, often using ballistics to cause two arrows to strike at once (shooting one on a high, slow arc to get around the horses' head armor and a second on a fast, shallow arc to punch through any weak spot in the French armor).

The second line panicked and thought that those in front of them needed help, adding to another quirk of the battlefield: the open space began to narrow as it neared the English position, forcing the French to bunch up. The mass was an unmissable target, and as they struck the English line they soon found that they were unable to use their weapons effectively. Even the lightly armed longbowmen had an advantage over the packed mass, and the French began to surrender en masse. A few thousand of the second wave made their way out while the third line never even budged except to leave the battlefield at the end.

The Battle of Agincourt. Each line is c. 1,000 men.

That would have been the end, except that a thousand French peasants had shown up and began to loot the English baggage train while they were distracted. Malcolm, thinking this a French sneak attack, ordered the execution of his prisoners before they could fall into enemy hands. Obviously, this was not a popular move, but it was carried out. Rather than 6,000 captured, the death toll was now 7,000 dead. Malcolm had lost only a few hundred (certainly less than a thousand), and would soon have 15,000 more at his side.

The French war now turned upside-down. Malcolm pushed towards Paris and had it under siege by mid-August. He began negotiating with Jean, Duke of Burgundy, a negotiation that began to create good fruits. However, the "Dauphin" (heir to the French throne), Etienne II, also invited him to a negotiation at Montereu. It was a trap: The duke and his bodyguard were set upon and killed, and the duke's heir, Phillip III, got the message. England would have no help from that end. Worse, France began negotiating with the kings of Castilla and Aragon to lend their aid once they could get peace with the Moors.

Still, things continued well. Malcolm captured Paris on 17 February 1420, and managed to convince Asclettin to sign a humiliating agreement that made Malcolm his heir (stating that Etienne was illegitimate, a charge that very well may have been true considering the reputation of Asclettin's wife). While France was technically out of the war, Etienne continued fighting from his power base in the southern part of the country. Malcolm also married Asclettin's daughter Catherine, to replace his first wife, who had recently died and had not given him a son.

The wedding of Maelgwn and Catherine de Blois.

This was when things began to turn. Malcolm's expedition into Nivernais was met by Etienne's army, with the Spanish now beginning to show in force. Scottish and Irish reinforcements were not enough to turn the tide, and Malcolm began to pull back. Fighting soon focused on the region around Blois. The battle went back and forth well into 1421, and in a series of battles the French finally managed to regain the city. Malcolm managed to get another large force (now near the limits of his money and manpower) and begin besieging the city again, but when another expedition into Nivernais failed in July 1422, both Maelgwn and Etienne agreed that there needed to be a rest. The English gained Picardy and the region around Paris, along with a restatement of the earlier agreement, given the official title of the Treaty of Troyes.

Malcolm would not be able to enjoy the fruits of his apparent victory. Having contracted dysentery in the fighting, he took ill and, on 31 August 1422, died. He had only his young son (less than a year old) Ioan II to survive him as king. Had Malcolm survived, he could have accepted at least an offical inheritance two months later with Asclettin's death.

__________

*Other estimates range from making the French advantage only 2-1 (10,000 to 20,000) to an astounding and almost certainly false 6-1 (6,000 to 36,000).

Last edited:

Maelgwn seems to be weird Welsh version of Henry V. They look the same. Do similar deeds and even died on a same day.

No St. Crispin's day speech? I like the analogy, it's always a shame to lose such a gifted king early, and much like with Henry V, a real tragedy for the English. Who will be regent in France and England respectively I wonder?

Olaus Petrus said:Maelgwn seems to be weird Welsh version of Henry V. They look the same. Do similar deeds and even died on a same day.

I fully agree. Let's hope that Ioan doesn't end like Henry VI...

JimboIX said:No St. Crispin's day speech?

Well, you see, the battle wasn't fought on St. Crispin's day.

Oh, I'd already begun working on that, but I figured I needed to get the update in first and have fun afterwords. If you're curious what Shakespeare might have been like in such an unusual world:

WEST.: O, þat we nou haft her

But a' ten þusend of þase menn in England

þat do noght worc todey.

KING: Hwat's he Þat wisceþ so?

My nighmay Westmerland. Ney, my cirt may,

If we sind merct to dea, we sind yenou

To do our homland lire: and if to libe,

Þe fewre menn, þe greatre scere of aring.

...

Þis lorespell scall þe good mann learn his sun;

And Samson of Yorc scall nefre go by,

From Þis dey to Þe ending of Þe world,

But in it scall efer be gemindwerþ,

We few, we sely few, we bund of broþren.

For he todey þat scedþ his blod wiþ me,

Scall be my broþer, be he ne're so liþ'ful,

Þis dey scall soften his aredness.

And eþelmenn in England, nou a bedd,

Scall þenc þemselfs a courst þey wern ney her,

And held þeir mannhads chep, hwil awight spricþ,

Þat fought wiþ ous uppan Sant Samson's dey.

I'm too lazy to come up with something to show how it's supposed to be pronounced right now. I might break out the IPA later, I don't know...

The original, for comparison (of course, it's not a 1-to-1 translation):

WEST.: O, that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England*

That do no work today.

KING: What's he that wishes so?

My cousin Westmorland. No, my fair cousin,

If we are mark'd to die, we are enough

To do our country loss: and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honor.

...

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall never go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers:

For he today that sheds his blood with me,

Shall be my brother, be he ne're no vile,

This day shall soften his condition.

And gentlemen in England, now abed,

Shall think themselves accurst they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap, whiles any speaks,

That fought with us upon St. Crispin's day.

__________

*That's actually 11 syllables, but complain to Will Shakespeare about that, not me.

looks like you've done well for yourself so far, hopefully you'll be able to hold the throne, unlike Henry VI

Hwat's he Þat wisceþ so?

Is it heresy to prefer phargle's free-verse or this translation over the original Shakespeare?

(At least 99% of it, he has some good spots on his own but i can't stand the filler.)

((And half of the remaining 1% was probably plagiarised anyway.))

Is it heresy to prefer phargle's free-verse or this translation over the original Shakespeare?

(At least 99% of it, he has some good spots on his own but i can't stand the filler.)

((And half of the remaining 1% was probably plagiarised anyway.))

I love the...what language are you calling that nowadays..? Speech and translation. Makes for an amusing bit, hope the alternative history continues apace...the war of the roses should be interesting, who will be your York? Of course, you never have a Richard III to be usurped and create the whole division, but still. This alternative Universe's development has been fascinating to watch.