JimboIX: We're not to the civil war yet... there's other triggers for that mess.

RGB: If only I could...

Kurt_Steiner: Again, if only I could...

Olaus Petrus: And how might I go around doing that? The French are even stronger now!

- - - - - - - -

It likely can never be known what mental effect the loss of the French posessions had on the young king Ioan; what few writings of his are available never once mention the events of his youth. He was certainly old enough by 1429 to understand the basic implications of such an event, and there was probably some connection to his later full-blown mental problems. At the time, however, Ioan took it mostly in stride, as he could rely on the regency council to control the country while he dealt with his education and the other various matters more pertinent to a child of his age.

The council was not so sure of the situation, however. Even after the end of the war, things were moving at rapid pace in various directions. The French moved in to eradicate the English language and culture which had moved into Normandy over the past century, pushing the region into periodic revolt; unfortunately, the poor economic situation which the previous war had caused prevented the English from supporting any of these revolts. The Count of Burgundy seized Hainaut before it could be taken by Jacoba of Bavaria, the Countess of Friesland. Jacoba's husband, the Duke of Gloucester, fervently petitioned the council to intervene in the matter. France backed Burgundy, however, preventing the English from taking any part in it.

Jacoba von Wittelsbach, Countess of Friesland

Even England itself was not in a good state. The nobility had begun to be restless with one another, as Robert, Duke of Cornwall, began getting in a feud with the Earl of Somerset. This almost devolved into open fighting, until the regency council carefully stepped around the issue and pushed the status quo. Realizing that if either made the first move they would have the force of the rest of England against them, both Cornwall and Somerset backed off. This problematic event was soon followed, in 1432, by an outbreak of plague in the southern reaches of the country. For four more years England was forced to deal with internal matters, until an outside event changed things.

In early 1436, Jacoba of Bavaria died. Gloucester immediately asked for permission to try for the inheritance of Friesland, and gained the regency council's approval--although the council flatly denied any aid from their part. Before Gloucester could even arrive, however, the Frisians, forming an alliance with the rulers of Oldenburg and Muenster, found a local ruler to control their region. Gloucester called for help, and above the grumbles of the council came a new voice: Ioan II, now fourteen and determined to assert his authority. He dissolved the council, already having Gloucester's support (obviously) and soon that of his relative the Duke of Cornwall as well. An English army under Cornwall moved into Holland and, in April of 1436, began to press Gloucester's claim. The destruction of the Frisian army was swift, and by September Frisia itself was in English hands.

Two other things stood in the way of a swift victory, however. First, Oldenburg and Muenster had large armies ready to move into Frisia and prevent Gloucester's inheritance. Second, part of the Frisian inheritance was Brabant, well to the south. Unable to be in both places at once, Cornwall gained Henry's approval in allowing the Count of Geldre to attack Brabant. Cornwall himself struck into Germany, where the combined armies of Oldenburg and Muenster were waiting. The battle occured near Westerstede on 8 October 1436. Cornwall's 22,000 were outnumbered by the 25,000 Germans, but they were poorly led and divided between the Count of Oldenburg and the Bishop of Muenster. The Count was captured and the armies dispersed, knocking both out of the war in one quick action.

After a treaty was signed with the two ending their support of the Frisians, Cornwall began to look south to aid Geldre in their slow preparations to attack Brabant. Early in 1437, however, the noble feuds becoming epidemic in Britain at the time struck again. James Borkalan, the Duke of Lothian, was in the army with a small Scottish contingent. Also there were several of the Douglas clan, who had no love for the Borkalans. On 3 February 1437, James was assassinated, by an unknown man but no doubt with the aid of the Douglases. This did not effect England so much as it sent shock waves through Scotland. James was seen as a sort of unofficial representative of the Scots, and his killing nearly sparked a civil war in the region. As it was, vengance would come in 1452, when the second James Borkalan killed the head of the Douglas clan and executed a royal order breaking their power.

Geldre finally got their army moving and, in October 1437, took Brabant with Cornwall's aid. Geldre gained the region and Gloucester was formally installed as Count of Friesland, swearing allegiance to Ioan under the Duchy of Holland. Said duchy had basically become synonymous with the Dutch lands, a situation which at least linguistically lingers to this day.

France, meanwhile, had used the opportunity of England's distraction to attack Bretagne. English control of the region had rapidly dissolved, and Ioan barely raised a cry as the French, in a two-year campaign, took most of the duchy and only left the region of Cornouaille itself to its namesake dynasty. This caused an immediate uproar in England, but there was almost nothing for Ioan to do except risk the loss of Calais and possibly even Holland, and unacceptable outcome and not worth the slight chance of protecting Bretagne. King Etienne also began reforming the French taxation and military systems to make them even more resilient. In response, Ioan began to try and normalize relations with the French, securing a promise that he could marry Margaret, daughter of the Duke of Anjou, in 1445.

Margaret d'Anjou, in a later depiction

In the meantime, Ioan looked to deal with the long-standing rebellion in Iceland. It was a horribly unpopular and certainly foolish decision, as Iceland would take several years, many men, and much money to subdue. Whatever the case, in 1448, 20,000 English soldiers under Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, attacked and swept aside the small army that the Althing raised against the English. The English army would have to spend two winters in Iceland, however, and tens of thousands either died or became unfit to fight due to frostbite or other causes. More thousands were ferried from England and Scotland, while ships were smashed against rocks and ice. On 23 February 1444 the Althing finally agreed to submit, and the army could return home.

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, later known as the "Kingmaker"

The moderately successful outcome of the Dutch and Icelandic campaigns gave Ioan a small amount of breathing-room. This was not to say all was well in England, of course. Lollards still popped up from time to time, and a major revolt in Geldre threatened to weaken the position not only of that count but also England in the region. Cornwall led more than twenty-five thousand men to fight 24,000 rebels. He was able to put them down with few casualties. The region would be inflamed again in 1451, when a group of peasants feeling oppressed by the nobility raised a general revolt, coinciding with an abortive uprising in Kent under a man named Jack Cade. Again Cornwall quickly put them down, and Holland would remain peaceful for decades to come.

Peace was not in the future for England, however. Ioan's marriage to Margaret soon facilitated a general alliance with France, ending any possiblity of conflict between the two nations (even if Ioan maintained a claim to the French throne and to the Ypres region while France still claimed Calais). In 1454, this alliance found itself in war against the Pope in Verdun, along with the powerful Rhineland Palatinate. France required Ioan's help against the two, and Ioan sent it, as Warwick and 23,000 men marched south for Lorraine.

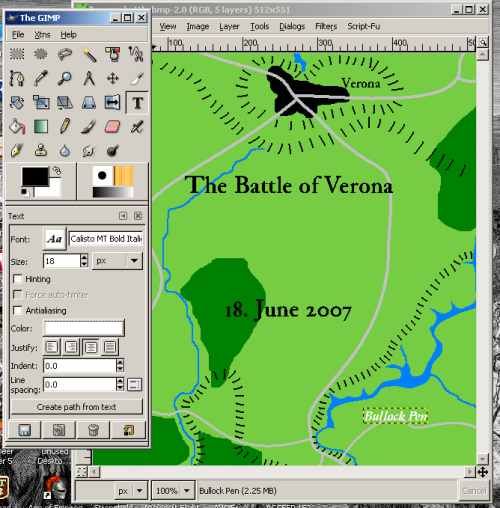

He arrived in the Nevers region in July 1454, as the French were being pushed back by an army of Friedrich von Wittelsbach, regent of the Palatinate for his nephew Philip and

de facto Elector Palatine. The sudden arrival of the English caused him to pull back into Lorraine. There, in October, he collected 25,000 men and met Warwick's army. In a quick battle on 29 October the Palatine army was decimated, although Warwick lost several thousand himself, and the English moved north towards the Rhine in an attempt to find a crossing-point.

Friedrich "the Victorious"

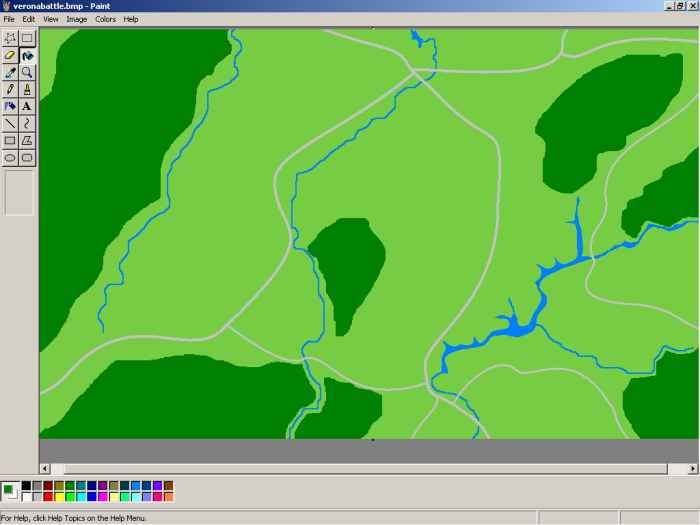

They found a crossing on 29 November and collected a dozen fairly sizeable barges to ferry the army across the river. This they did over several days, and by 5 December, aided by a fairly mild winter, they were ready to move through the town of Gross-Rohrheim to find the remnants of the Palatine army. They didn't have to go far: before the English had even gotten the supply-train moving out of the riverside camp, five thousand Palatine soldiers arrived to threaten Warwicks army of now 16,000, along with a booming cannon which only temporarily unnerved the English and had little effect on the rest of the battle.

It appeared like a deceptively stupid move, and Warwick thought that there would be a second attack from the south. This was a severe miscalcuation: There were indeed 3,000 more Palatine soldiers in the area, but in the north. Also attacking were four large river craft attempting to destroy the English barges. They managed to burn three, but at the cost of two of their number (one sank and the other, striking the wreckage of a half-sunken English ship, was disabled and forced to float back north with the current). The other two were rapidly overwhelmed by English soldiers on the remaining barges and captured.

Meanwhile, the Palatine flanking attack on the north arrived. It did so none too soon: Friedrich's plan had been ill-advised, as his men began to fall to pieces. The English camp was easily overrun (half the garrison had been brought forward to aid the rest of the English) but the frontal attack nearly broke completely. The flanking heavy cavalry arrived just in time to smash into the English flank. It bent, and mostly broke (especially as some of the English had moved further forward to pursue fleeing men from the frontal attack), but enough held to ensure most of the army remained in good order. Still, the route to the river was cut off by 7,000 tough Palatine soldiers, and only 6,000 of the English army remained in good enough condition to fight.

Warwick decied to save his army, and after a small counterattack gave an escape route for a small band of surrounded soldiers, he ordered his longbowmen to created a bristling porcupine of arrows. The Palatinate men had taken bad casualties and were now shy of charging the legendary longbows, allowing Warwick to withdraw in good order. An attempt by the soldiers who had ransacked the English camp to sieze the ships was repulsed and those moved upstream as well.

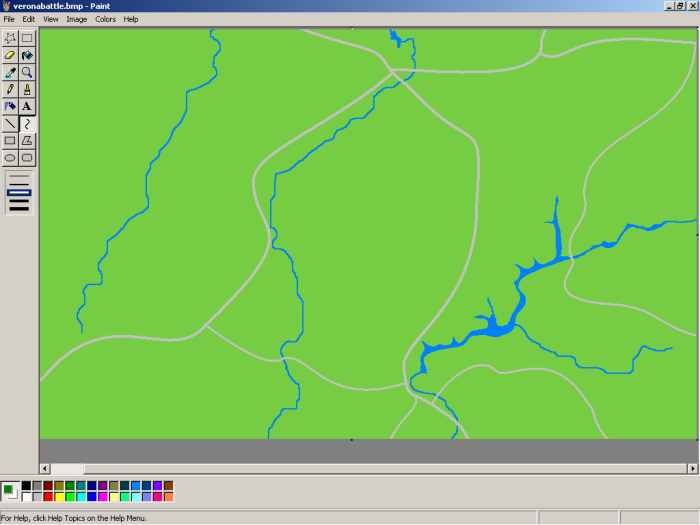

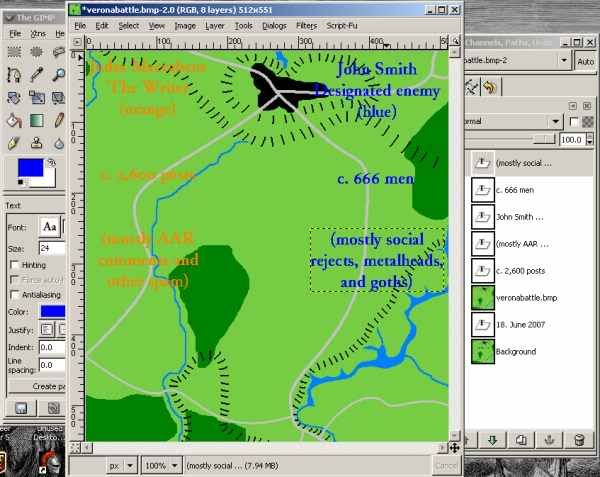

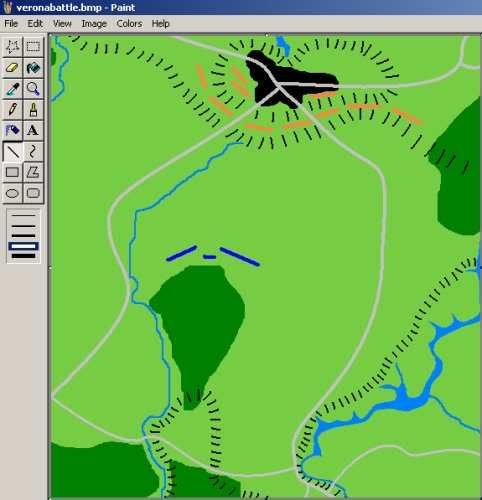

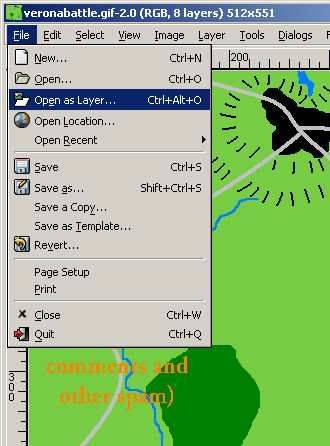

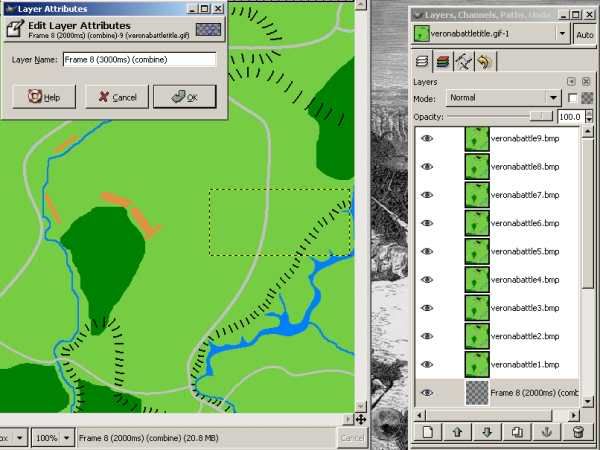

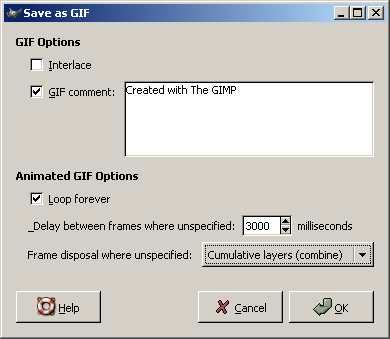

The Battle of Rohrheim. Each line is c. 1000 men.

Although Warwick's army had survived, it was not in a good position. Winter was coming, and the enemy might get reinforcements at any time, after they had already defeated the English army with their current number. Neither the Dukes of Baden to the south or the Archbishop of Cologne to the north agreed to let the English through their lands, and Friedrich would oppose any attempt to cross the Rhine. Warwick decided to give events a chance to play out, hopefully with the French drawing Friedrich's attention away with their large armies. Before that could happen, however, news arrived from England:

Civil war was at hand.