What a disappointment , although Charles himself was too practical for my taste anyway XD

O Lord, our God, Arise: More Weekly Reports from England

- Thread starter unmerged(10971)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Failed Kurt? Entirely successful one should say! Hurrah for reason and heroic virtue, displayed by youthful Oliver! Law and greatness overcome tyranny and treason!

[RGB: That we do. Nothing about freeing Scotland from vile Presbytry, I fear.

Morsky: Well, at least you've a happy ending. Perhaps you can visit the Old Pretender over in Ancona sometime.

Kurt_Steiner: Oliver and Charles both. It happened to work for one side, just not the other, because one side had his namesake great-great-grandfather's cavalry with him.

canonized: And you still wouldn't have gotten a Catholic-ruled Britain, since Charles had every intention of converting to Anglicanism when he took over.

English Patriot: Indeed. God save the Emperor!

Now, for those who support the true Emperor, some celebratory music. For the rest of you... well, you can always sing "Hwan þe Emp'ror Broocs his Aiwn Ondgain" ]

]

Thomas Arne's operas might not be quite so famous as those of other British composers such as Henry Purcell or Sir Arthur Sullivan, but at the time they were extremely popular, and some (such as his Artaxerxes) continued to be performed through the middle of the 19th century. One song from an opera of his did survive in the British consciousness, however. His 1740 masque (later made into an opera) Alfred contained this song:

The music (as originally in Arne's opera)

1.

Hwan Britain first, at Heaf'ns command,

Arose fram out þe scy-blue main;

Þis was þat yewrit of þe land,

And warding angels sang þis strain:

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

2.

Þe þeadscips, ney so blesst as þee

Must in þeir turns to tyrants fall;

Hwilc þou scalt blossom great and free,

Þe dread and unfest of þem all.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

3.

Still mair þrimwielding scall þou rise,

Mair dreadful, fram ealc outlandisc sliht;

As þe loud blast þat tears þe scies,

Serues but to root þy cen'dly oac.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

4.

Þee hauhty tyrants ne'er scall tame,

All þeir fandings to bend þee doun,

Will but arouse þy cistly flame;

But worc þeir woe, and þy renoun.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

5.

Þe fieldly rice belong'þ to þee,

Þy burys scall wiþ business scine:

All þine scall be þe hearsome sea,

And efery strand it faþoms þine.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

6.

Þe Muses, still wiþ freehood found,

Scall to þy happy rim repair;

Blest Isle! wiþ maceless certness croun'd

And mannly hearts to ward þe feir.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

Händel, as Thomas' court composer (and one of the few people who regularly conversed with the reclusive emperor), wrote not one but two oratorios in response to the Jacobite uprising of 1745. The first, the "Timely Oratorio" of February 1746, was a musical call-to-arms, quoting Luthers "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" and ending with a section from his own "Zadok the Priest". The libretto, by Newburgh Hamilton, borrowed from John Milton amongst others. Despite being written in haste, it was quite well-received.

After the victory, Händel again wrote an oratorio, this time with a more celebratory theme. Taken from the story of the 2nd-century BC rebellion of the Maccabees against the Hellenic Seleucids, Händel and his librettist, Thomas Morell, made the connection between Judas Maccabeus and their own ruler, Oliver II, quite unambiguous: the leader of his people marching out to strike down a foreign tyrant, and returning in triumph. The most famous piece from the oratorio is the triumphant march near the end:

The music*

57. Recitativo

First foreboder

Fram Capharsalama, I on arn-feaþers fly,

Wiþ tidings of redhided bliþe:

Came Lysias, wiþ his host, trimmed

In hacel of mail; þeir festly scields

Of gold and brass, flasct lightening o'er þe fields,

Hwile þe main tour-bac'd elepends appear'd

Ane horrid fore. But Judas, unafear'd,

Met, fouht, and oferswaþe all þe bremming train.

Yet mair, Nicanor lieþ wiþ þusands slain;

Þe blasphemous Nicanor, hwa unheld

Þe lifing God, and, in his gallful mood

A folcly sigebeacon ordain'd

Of sigefastness yet ungain'd.

Twam foreboder

But lo, þe ofercomer comeþ, and on his spear

To tobear all fear,

He bear'þ þe braggart's head and hand

Þat boasted wasteness to þe land.

58. Chorus

Youþs

|:See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.:|

Sports aread, þe laurel bring,

Songs of triomph to him sing.

Maidens

See þe godlice youþ advance,

Breaþe þe flutes, and lead þe dance;

Wire-wreaþ and roses twine,

Þe hero's godly brau to tine!

Youþs

See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.

Sports aread, þe laurel bring,

Songs of triomph to him sing.

See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.

59. Fare [instrumental]

__________

[Oh, come on, you had to have known I was going to pick this one, didn't you? ]

]

*Yes, yes, yes, I could only find versions in our real-life words, but what did you expect? The funny thing is, I decided to include "From Capharsalama" before I found a clip that included that part, I was expecting only to have "See the Conqu'ring Hero" to play.

The funny thing is, I decided to include "From Capharsalama" before I found a clip that included that part, I was expecting only to have "See the Conqu'ring Hero" to play.

Morsky: Well, at least you've a happy ending. Perhaps you can visit the Old Pretender over in Ancona sometime.

Kurt_Steiner: Oliver and Charles both. It happened to work for one side, just not the other, because one side had his namesake great-great-grandfather's cavalry with him.

canonized: And you still wouldn't have gotten a Catholic-ruled Britain, since Charles had every intention of converting to Anglicanism when he took over.

English Patriot: Indeed. God save the Emperor!

Now, for those who support the true Emperor, some celebratory music. For the rest of you... well, you can always sing "Hwan þe Emp'ror Broocs his Aiwn Ondgain"

Sources of English, no. 10

Alfred: "Hwan Britain first, at Heaf'ns command" (Risce, Britannia!)

by James Thomson (music by Thomas Arne)

Alfred: "Hwan Britain first, at Heaf'ns command" (Risce, Britannia!)

by James Thomson (music by Thomas Arne)

Thomas Arne's operas might not be quite so famous as those of other British composers such as Henry Purcell or Sir Arthur Sullivan, but at the time they were extremely popular, and some (such as his Artaxerxes) continued to be performed through the middle of the 19th century. One song from an opera of his did survive in the British consciousness, however. His 1740 masque (later made into an opera) Alfred contained this song:

The music (as originally in Arne's opera)

1.

Hwan Britain first, at Heaf'ns command,

Arose fram out þe scy-blue main;

Þis was þat yewrit of þe land,

And warding angels sang þis strain:

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

2.

Þe þeadscips, ney so blesst as þee

Must in þeir turns to tyrants fall;

Hwilc þou scalt blossom great and free,

Þe dread and unfest of þem all.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

3.

Still mair þrimwielding scall þou rise,

Mair dreadful, fram ealc outlandisc sliht;

As þe loud blast þat tears þe scies,

Serues but to root þy cen'dly oac.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

4.

Þee hauhty tyrants ne'er scall tame,

All þeir fandings to bend þee doun,

Will but arouse þy cistly flame;

But worc þeir woe, and þy renoun.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

5.

Þe fieldly rice belong'þ to þee,

Þy burys scall wiþ business scine:

All þine scall be þe hearsome sea,

And efery strand it faþoms þine.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

6.

Þe Muses, still wiþ freehood found,

Scall to þy happy rim repair;

Blest Isle! wiþ maceless certness croun'd

And mannly hearts to ward þe feir.

"Risce, Britannia! Risce þe waves:

Britons neuer will be slaves."

Judas Maccabaeus: Recitativo ("Fram Capharsalama") and Chorus ("See, þe sigerice hero com's!")

by Thomas Morell (music by Georg Friedrich Händel)

by Thomas Morell (music by Georg Friedrich Händel)

Händel, as Thomas' court composer (and one of the few people who regularly conversed with the reclusive emperor), wrote not one but two oratorios in response to the Jacobite uprising of 1745. The first, the "Timely Oratorio" of February 1746, was a musical call-to-arms, quoting Luthers "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" and ending with a section from his own "Zadok the Priest". The libretto, by Newburgh Hamilton, borrowed from John Milton amongst others. Despite being written in haste, it was quite well-received.

After the victory, Händel again wrote an oratorio, this time with a more celebratory theme. Taken from the story of the 2nd-century BC rebellion of the Maccabees against the Hellenic Seleucids, Händel and his librettist, Thomas Morell, made the connection between Judas Maccabeus and their own ruler, Oliver II, quite unambiguous: the leader of his people marching out to strike down a foreign tyrant, and returning in triumph. The most famous piece from the oratorio is the triumphant march near the end:

The music*

57. Recitativo

First foreboder

Fram Capharsalama, I on arn-feaþers fly,

Wiþ tidings of redhided bliþe:

Came Lysias, wiþ his host, trimmed

In hacel of mail; þeir festly scields

Of gold and brass, flasct lightening o'er þe fields,

Hwile þe main tour-bac'd elepends appear'd

Ane horrid fore. But Judas, unafear'd,

Met, fouht, and oferswaþe all þe bremming train.

Yet mair, Nicanor lieþ wiþ þusands slain;

Þe blasphemous Nicanor, hwa unheld

Þe lifing God, and, in his gallful mood

A folcly sigebeacon ordain'd

Of sigefastness yet ungain'd.

Twam foreboder

But lo, þe ofercomer comeþ, and on his spear

To tobear all fear,

He bear'þ þe braggart's head and hand

Þat boasted wasteness to þe land.

58. Chorus

Youþs

|:See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.:|

Sports aread, þe laurel bring,

Songs of triomph to him sing.

Maidens

See þe godlice youþ advance,

Breaþe þe flutes, and lead þe dance;

Wire-wreaþ and roses twine,

Þe hero's godly brau to tine!

Youþs

See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.

Sports aread, þe laurel bring,

Songs of triomph to him sing.

See, þe sigerice hero com's!

Sound þe trumpets, beat þe drums.

59. Fare [instrumental]

__________

[Oh, come on, you had to have known I was going to pick this one, didn't you?

*Yes, yes, yes, I could only find versions in our real-life words, but what did you expect?

Last edited:

BTW, my little and dear Padawan, you, Judas. Because of you, I've decided to download the Enge-land scenario for CK.

Any possible AAR based on it by my part will be your fault. The whole fault.

And, please, someone, kill the Cromwell bastard, please.

Any possible AAR based on it by my part will be your fault. The whole fault.

And, please, someone, kill the Cromwell bastard, please.

Kurty: I'd be willing to accept the mea culpa for any CK AARs you might make.

Some notes on pronunciation for this alternate English, since it's changed from the Middle English of the last pronunciation guide I've made:

The Great Vowel Shift worked pretty much the same as from the original, so unless I note a difference assume it's about the same. For our first bit, we'll work out the pronunciation of "sigerice" (victorious).

"C" is a bit of an odd duck in this spelling, so the main bit will be to go into it's various foibles. Before consonants, of course, it's always hard (the "k" sound), as before a, o, and u. Before i or e, it can do one of two things: the soft "s" sound, or a "ch" sound. It's somewhat of a dialectical thing which goes where. The general, "official" way is "ch" before both (therefore, "cise" is "cheese" in this speech, and pronounced mostly the same. I'll get to the different vowel pronunciations in a moment). It also becomes "ch" after l at the end of a word, thus "swilc" (such) is pronounced "swilch" (or "silch", depending on dialect).

"G" does a generally similar thing. In other words, like in our English.

"Sc" is still an "sh" sound. It can also be spelled "sch", but that's on the wane.

The main difference in vowel pronunciation is that "i" doesn't do the same thing that other vowels do with a silent "e" at the end of a word; therefore, "cise" would be pronounced "chiz", not "cheiz".* The main thing the silent e does is make an intermediate "s" vocalised, and the "c" a "ch" rather than "k".

"Sigerice", therefore, is something like "sidjrich". "Maceless" would be pronounced "maichless", "-lice" is "-litch", and so on.

It won't be until the later part of the century that Britons get in the habit of regularly using "v" instead of "u", so "neuer" (itself a nonstandard variant of "nefer, both pronounced the same) is "never". That also makes the point that "f", like "s", sometimes becomes voiced. Britons won't get much into the habit of changing that one, except in rare cases like Arne's "neuer".

"H" is also a bit of a fun one. As you might notice, it hasn't been replaced by "gh" in words like "sliht"; the pronunciation isn't usually that much different ("sliht" is still "slite"), although "lauh" is "lakh" and not "laff" (and "rouh" is "rukh" and not "ruff"). "Liht" is still "lite", "þouht" is still "thott", "þrouh" is still "thru", etc.

That should generally get the point across. I supose sometime I could read out one of those things to get the point across better, although I'd feel kind of silly doing it.

Some notes on pronunciation for this alternate English, since it's changed from the Middle English of the last pronunciation guide I've made:

The Great Vowel Shift worked pretty much the same as from the original, so unless I note a difference assume it's about the same. For our first bit, we'll work out the pronunciation of "sigerice" (victorious).

"C" is a bit of an odd duck in this spelling, so the main bit will be to go into it's various foibles. Before consonants, of course, it's always hard (the "k" sound), as before a, o, and u. Before i or e, it can do one of two things: the soft "s" sound, or a "ch" sound. It's somewhat of a dialectical thing which goes where. The general, "official" way is "ch" before both (therefore, "cise" is "cheese" in this speech, and pronounced mostly the same. I'll get to the different vowel pronunciations in a moment). It also becomes "ch" after l at the end of a word, thus "swilc" (such) is pronounced "swilch" (or "silch", depending on dialect).

"G" does a generally similar thing. In other words, like in our English.

"Sc" is still an "sh" sound. It can also be spelled "sch", but that's on the wane.

The main difference in vowel pronunciation is that "i" doesn't do the same thing that other vowels do with a silent "e" at the end of a word; therefore, "cise" would be pronounced "chiz", not "cheiz".* The main thing the silent e does is make an intermediate "s" vocalised, and the "c" a "ch" rather than "k".

"Sigerice", therefore, is something like "sidjrich". "Maceless" would be pronounced "maichless", "-lice" is "-litch", and so on.

It won't be until the later part of the century that Britons get in the habit of regularly using "v" instead of "u", so "neuer" (itself a nonstandard variant of "nefer, both pronounced the same) is "never". That also makes the point that "f", like "s", sometimes becomes voiced. Britons won't get much into the habit of changing that one, except in rare cases like Arne's "neuer".

"H" is also a bit of a fun one. As you might notice, it hasn't been replaced by "gh" in words like "sliht"; the pronunciation isn't usually that much different ("sliht" is still "slite"), although "lauh" is "lakh" and not "laff" (and "rouh" is "rukh" and not "ruff"). "Liht" is still "lite", "þouht" is still "thott", "þrouh" is still "thru", etc.

That should generally get the point across. I supose sometime I could read out one of those things to get the point across better, although I'd feel kind of silly doing it.

I feel like being in my old days at university, being on the receiving end (pun intended) of my classes of history of that charming language called English.

The Great Vowel Shift.... grrrrrrrr...

grrrrrrrrrr...

The Great Vowel Shift.... grrrrrrrr...

grrrrrrrrrr...

More music that I never heard before, and I must say, I like this pronunciation guide better. It is closer to how I read it anyway

Kurty:  Can't help it, such is the way of things. English is a mess, I know, I know. I'd rather it made more sense, but even in this alternate version of things I only have so much control over that.

Can't help it, such is the way of things. English is a mess, I know, I know. I'd rather it made more sense, but even in this alternate version of things I only have so much control over that.

RGB: Now now now, I'm sure you've heard "Rule Britannia", at least. The bit from Judas Maccabaeus (that oratorio, incidentally, is actually what inspired my user name) is somewhat more obscure, though, so I'll grant you that one.

The bit from Judas Maccabaeus (that oratorio, incidentally, is actually what inspired my user name) is somewhat more obscure, though, so I'll grant you that one.

Still working on the first part of Oliver's glorious reign; the last night of the Proms was both a nice inspiration for, and somewhat of a distraction from, working out more of this AAR.

RGB: Now now now, I'm sure you've heard "Rule Britannia", at least.

Still working on the first part of Oliver's glorious reign; the last night of the Proms was both a nice inspiration for, and somewhat of a distraction from, working out more of this AAR.

Oliver II the Farmer

Born: 4 June 1725, Reading

Married: Elisabeth Augusta von Zähringen (on 16 March 1748)

Died: 24 July 1777, Baden

Born: 4 June 1725, Reading

Married: Elisabeth Augusta von Zähringen (on 16 March 1748)

Died: 24 July 1777, Baden

Titles: (claimed but unrecognised in brackets)

Emperor of Great Britain

King of Ireland [and France]

Prince of Wales

Lord of the Scottish [and Greek] Isles

Duke of Lothian, Albany, [Holland and Friesland], Flanders, Cornwall, [Iceland] and Bretagne

[Count of Guines]

Supreme Governor of the Church of England

"So that Lancashire merchants whenever they like

Can water the beer of a man in Klondike

Or poison the meat of a man in Bombay;"

Can water the beer of a man in Klondike

Or poison the meat of a man in Bombay;"

- G.K. Chesterton, "Songs of Education"

Oliver's first order of business upon returning from Scotland in 1747 was to replace the squabbling government that had nearly brought disaster on Britain. Some, such as Newcastle, had removed themselves by siding with the Borcalans and then fleeing after Charles' defeat; others, such as Bath and Harrington, were removed by Oliver instead. Parliament was only too happy to help with fixing the problems that had led to the mix-up; the Northern and Southern departments were replaced with the Home and Foreign departments. The new Home Secretary was John Russell, Duke of Bedford, and a close friend of Oliver's (this friendship would aid both him and his family soon enough); the Foreign Secretary was Philip Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield. Above all of these, the new Lord Treasurer, and thus First Minister, was John Carteret, Earl Granville. Granville, a fluent speaker of German (as Oliver would become in later years), had spent many of the previous years in the Palatinate, and helped Oliver with his intention of strengthening the reeling League of Augsburg, not only with Baden and the Count Palatine, but with Austria as well.

John Carteret, Earl Granville, by William Hoare (unknown date)

Although early negotiations (during Thomas' reign) to marry Oliver with Maria Theresa of Austria fell though, mostly due to distaste in the various courts of Europe to the idea of Britain, Austria, and Spain all being in a personal union, the next option, a marriage to Elisabeth Augusta, the eldest daughter of the Holy Roman Emperor, succeeded, and Elisabeth and Oliver married in early 1748. At the same time, he took part in the negotiations between Baden and the Helvetian Confederation over Schaffhausen near Lake Constance; a short war broke out despite his efforts in 1748, resulting in the town and the area around it going to Baden, and the border between the two countries being set along the Rhine river (except near Basel, where the Prince-Bishop was allowed to retain his small region across the river).

Oliver himself was busy in Britain; unlike his father, he played an active role in many daily affairs wherever the Instrument allowed him to, and leaned minor pressure in other areas, especially through Bedford. One was agricultural reform; he helped introduce the Continental four-field system, among other minor things. The result was that the young Emperor became known as "Farmer Oliver", or the "Digger King" by those less inclined to think well of him. His meddling through the thus-unpopular Bedford strained the government he had set up, along with his own reign, but he never quite reached the point that Parliament would react from, as the more conservative, constitutionalist Whigs were in power at the time rather than the more radical Patriots or Levellers. More importantly, there was an agricultural boom in the early portions of his reign, giving the sense that his (or at least Bedford's) efforts were actually working.

John Russell, Duke of Bedford, by Joshua Reynolds (1762)

In the meantime, the war against the Marathi had ended, with Wolfe and another notable commander, Robert Clive, forcing them to surrender the important coastal cities of Bombay and Surat to the East India Company. The British presence in India was rapidly expanding, with Spanish and French efforts practically gone, the Portuguese limited to Goa, and the Dutch still only able to influence portions of Gujarat and Kerala. In contrast, the British controlled Calicut, Bengal, and the coast of Maharashtra directly (the three "Presidencies" of Calicut, Calcutta, and Bombay), and could claim some influence in the rest of Maharashtra, as well as the state of Mysore that dominated southern India at the time.

The end of Richard Cromwell's line of descendants, the Earls of Huntingdon, in 1748 returned that inheritance to Oliver II, leaving Henry's as the senior line of the Cromwell family. It also emphasised how much the family tree had been trimmed down over the years; what did not help matters was that Oliver's only son, of the same name, was quite sickly and died in 1753 at the age of five. Concerns as to near-sterility were raised in some areas, and Oliver's brother Henry made a show of ensuring that he at least had heirs of his own were he needed to inherit. Unfortunately, the show was an unsuccessful one, and none of the other sons of Henry IV or Henry V had sired any children. Oliver's sister, Ann, would soon marry Georg von Braunschweig-Lüneburg, the Elector of Hanover, and the marriage would result in several children starting in 1762; the idea of a Protestant ruler from a minor state inheriting wasn't quite so terrible a possibility.

Before the matter came up, however, the problems surrounding Bedford's unpopularity came to a head. The beginning of the troubles was in 1754, when a political ally of Bedford's, George Spencer, the heir to the Duke of Marlborough, began running into financial difficulty. Unable to get any help from his more financially sound father, Spencer approached Bedford, who then asked the Emperor to provide for the noble. Oliver was only too happy to help, giving him a sizeable amount of money and securing him a position as a captain in what would become the Lancashire Fusiliers. None of it was problematic or unusual in and of itself; the problem was that it highlighted the belief among the rest of the British government that Oliver was under Bedford's thumb.

Discontent with the government forced Oliver to dissolve it, and Parliamentary elections in 1755 returned strongly in favour of the Patriots, ending the Granville government. The new Lord Treasurer and thus First Minister (not a Patriot himself, but at least willing to go along with them) was William Cavendish, the Duke of Devonshire. Bedford's replacement as Home Secretary was the main rising figure in the Patriot party, William Pitt. Pitt was the more dynamic of the two, and, much to Devonshire's (and Oliver's) annoyance, often acted as if he were First Minister himself. It was obvious that the situation would not last in its current state for long; all that was required was one event to shake it up entirely.

That event was skirmishing in America. In 1753, the governor of South Carolina, James Glen, complained to the French governor of Louisiana that Frenchmen from that colony had been partaking in piracy along the Atlantic coast, and that several had been captured and executed for that act. Said governor claimed ignorance, but the sudden (if unsuccessful) wave of piracy did not end. Use of the semi-centralised American militia was controlled by the Council of State's Board of Trade; said board approved a punitive expedition in 1754. The first attempt, a scouting expedition led by Lieutenant-Colonel George Washington of Virginia, set a small fort in French territory but was overrun. A second expedition in 1755, led by General Edward Braddock, was an absolute disaster; at the Battle of the Savannah next to the South Carolina-Louisiana border on 9 July, the British force was nearly wiped out, with most of the British commanders (with a few exceptions such as the apparently-invulnerable Colonel Washington) either killed or wounded; Braddock himself was among those dead.

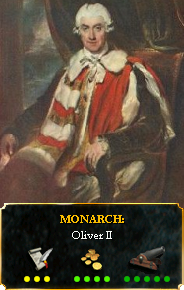

Braddock's death, by an unknown engraver (19th century)

Devonshire was against the expeditions, stating that provocation of the French and incidents such as those were hardly necessary; on the other side, Pitt was specifically calling for war against France to remove their American possessions and expand the British colonial empire. Oliver sent a complaint to the French king regarding the apparently-supported pirate activity, which resulted in no response. The British ambassador in Paris was recalled and the matter put before Parliament, with a request from the Emperor for an authorisation of military action; on 28 April 1756, after considerable debate, Pitt's supporters won out, and Parliament set forth a declaration of war. Devonshire soon resigned, with Pitt taking his place as Lord Treasurer and First Minister; he had both his war and his ministry now.

Ooh, a war. And the irony of a "Farmer King" being barren.  Too bad the Stuart line has been reduced to a syphilitic drunkard and a gay priest - they could have had a shot. Eh well.

Too bad the Stuart line has been reduced to a syphilitic drunkard and a gay priest - they could have had a shot. Eh well.

[Morsky: What are you talking about?  The Stuarts are alive and well and have the Earldom of Bute in Scotland. The drunkard and priest are the Borcalans... I think you're a little confused.

The Stuarts are alive and well and have the Earldom of Bute in Scotland. The drunkard and priest are the Borcalans... I think you're a little confused.

Kurt_Steiner: Sorry to let you down, but I'm afraid the Borcalans are out of commission from now on. Something of a museum piece, really, as they'll die out soon enough in any case.]

250th Anniversary of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham Special: The French and Indian War

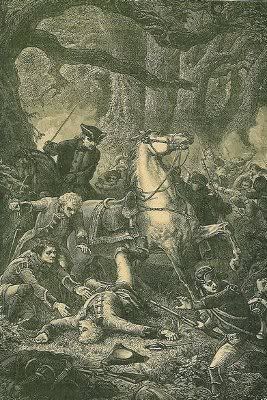

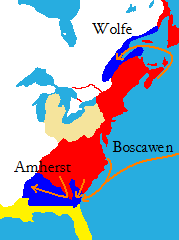

Unusually for a war between Britain and France, Flanders was left untouched during the opening stages. Small skirmishes on the Breton border during May of 1756 were inconclusive; for both sides, the main focus of the early fighting was America. Britain's plan involved three armies: The northernmost, under the command of James wolfe, was tasked with the capture of the city of Quebec; the southeastern, commanded by Admiral Edward Boscawen, was tasked with the capture of the port of Savanne and the other seaports of Louisiana; the southwestern, under Jeffery Amherst, was to destroy the French armies in Louisiana and take the forts in Alabama and along the Mississippi River. On all fronts, the British outnumbered the French; despite this, however, the British army expected a measure of difficult resistance against their advance, especially in Quebec.

Eastern America at the outbreak of the French and Indian War, 1756

The plan had an auspicious start; on 3 July 1756, Boscawen's fleet, fresh from Norfolk and Bermuda, appeared off the coast of Louisiana, with his land forces waiting across the Savanne River. Both sides knew that the army was a mere formality, however; the fate of the city would depend on whether or not the French could turn back Boscawen's fleet. His flagship was the new, massive 100-gun HMS Emperor Oliver. Although both the British and French had approximately equal numbers of ships of the line rushed from Europe, around twenty, the former outgunned the latter by no small amount. The French line of battle was torn apart, six ships being sunk, and the Formidable of 80 guns captured by the smaller HMS Dreadnaught of Captain Maurice Suckling. Savanne surrendered without a land battle upon seeing the display, and the possibility of French reinforcement of their American colonies became slight indeed.

Unfortunately for the British, that first success was tempered by other news. Amherst had advanced into Alabama in May; he was constantly harassed by the local Creek natives, who had allied themselves solidly with France. On 25 May 1756, along the Coosa River near where Gadsden is today, his army was badly defeated by a combined French and Creek army and forced back north. It had become distressingly obvious that usual British tactics were infeasable in the dense forests of Louisiana, especially against the more effective native tactics employed by the Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes of western Louisiana. A second attempt later in the year came to a similar end on 17 August, and Amherst was removed and replaced with Thomas Gage. Gage recognised the need for a light infantry force to fight properly in the wilderness of America, and already had raised a regular regiment of such before his appointment. He did not have much time to act, as the French and Creek were already advancing into British-settled territory.

Thomas Gage, by John Singleton Copley (1769)

Gage had two armies to work with, and he intended to make the most of them. The lighter force under his own command would march south, into Creek territory, then swing westward to pacify the rest of Louisiana. A more traditional force, under the Swiss-born Frederick Haldimand, had the simpler task of finishing out the more French-settled regions closer to the coast. Most of the French militia there had been drained in attempts to retake Savanne or the other coastal settlements, and there was little resistance to Haldimand's advance. Gage had the tougher task, as the French-Creek army had already pushed as far north as Huntsville across the Tennessee River, burned on 9 November. With no time to properly train his army, Gage had to hope that they were enough, and met the enemy on 18 November 1756 at Sulphur Springs north of Huntsville. His new, lighter regiments tore through the surprised and still somewhat traditional French, and held their own against the impressed Creek. With the French military presence in Louisiana practically eliminated, the Creek and Choctaw agreed to peace with the British soon after. Louisiana was firmly and permanently in British hands.

Wolfe had both success and failure in his portion of the war. Having set out from Nova Scotia in July, an advance squadron tested the defences of Quebec City on 30 July 1756; the main force advanced more slowly, as the French forts at Riviere-du-Loup, Montmagny, and Ile d'Orleans needed to be taken first. The result was to delay Wolfe by a month, but apparently the French had not taken his advance seriously; half the French army had been sent southward, leaving around 8,000 men under Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis of Saint-Veran. Wolfe's force was slightly larger, at around 12,000; he realised to both relief and shock that he would have been outnumbered had Montcalm not sent the other army south. As it was, he prepared his bold plan to take the city quickly, without a long siege. On the night of 27-28 August 1756, Wolfe's army set off from the Ile d'Orleans around 5 kilometers northwest of Quebec City, where he had been facing off against Montcalm's main force, and sailed quickly up the Saint Laurence river to a point just south of the town itself.

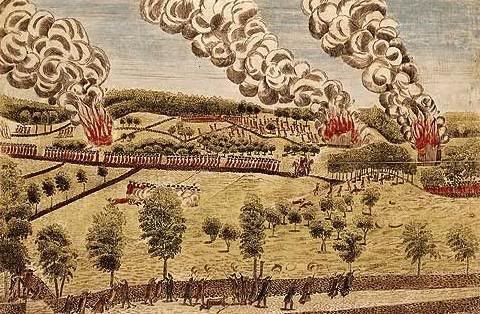

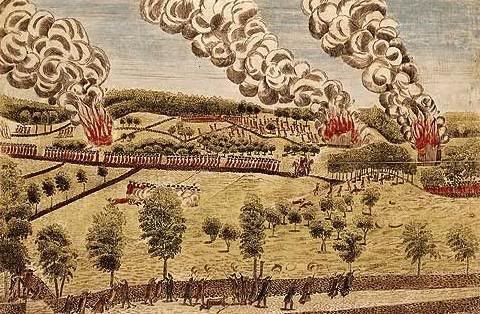

As dawn broke on 28 August, Montcalm was shocked to find that Wolfe's army had scaled the high cliffs leading up to the open Plains of Abraham just soutwest of the city itself. He had no choice but to rush his army southward as quickly as possible, as the alternative was to allow Wolfe to march into the Chateau Saint-Louis that protected the city almost unopposed. He barely managed to get his force in place before noon, and the two armies struck each other. Not only did Wolfe outnumber Montcalm, but his army was nearly entirely trained regulars, while Montcalm had a mixture of regulars and French militia. The battle only lasted 15 minutes; but in the sharp fighting, Wolfe, taking to a small rise just behind his lines, was struck in the chest by two bullets. His opponent, Montcalm, suffered a similar fate, as in the French rout he was mortally wounded in the abdomen. The shattered remnants of Montcalm's army surrendered to Wolfe's second-in-command, William Howe.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Each line is c. 1000 men.

The Death of General Wolfe, by Benjamin West (1770)

In death, Wolfe had secured Quebec for Britain. Eventually, Montreal would fall to Howe in December of 1757, completing the conquest of Lower Canada. The war was far from over yet, however, as the French army that had been sent south was still at large. In fact, it had been surprisingly successful; under the command of Francois de Levis, it easily dealt with the small militias of New York and New Hampshire to bring about general panic in New England. De Levis' force reached the outskirts of New York, and even took portions of northern New Jersey. The New Jersey militia was defeated outside Trenton on 7 December 1756, and for a time it seemed that New York, and with it New England, would fall. De Levis was acting on borrowed time, however, as without Quebec he had little hope of supply or reinforcements. Despite defeating the Massachusetts militia at White Plains north of New York City on 6 May 1757, he was already facing a larger force from the south. A combined, semi-regular American army had been organised, and placed under the command of now-general George Washington. Although only a mediocre tactician, Washington was a master strategist, and knew precisely how to deal with the French army with a minimum of fuss. After a short period of manoeuvre, Washington defeated the army in detail at Cross River, New York on 28 June 1757 and Redding Ridge and Easton, Connecticut on 29 June. All America north of the Spanish holdings of Texas and Florida was now firmly in British hands.

The war in Europe was almost an epilogue. Battles went back in forth in Flanders and Artois in 1757, with both French and British winning close battles, neither army being rid of each other. The French had finally developed a plan to defend the Breton border, as well, and it took a considerable amount of fighting to near Blois. Finally, on 25 May 1758, a British army swept the slightly larger French aside at Cheverny on 25 May 1758. Blois fell a month later, and once again France was forced to the peace table by the humiliating capture of their capital. The negotiations had already been ongoing; the capture of Blois was simply the trigger for France to cave in to the total loss of their American possessions (several Caribbean islands were taken by Portugal as well). Pitt's imperial ambitions had been fulfilled; Britain now had nearly an entire continent to call her own.

Kurt_Steiner: Sorry to let you down, but I'm afraid the Borcalans are out of commission from now on. Something of a museum piece, really, as they'll die out soon enough in any case.]

250th Anniversary of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham Special: The French and Indian War

Unusually for a war between Britain and France, Flanders was left untouched during the opening stages. Small skirmishes on the Breton border during May of 1756 were inconclusive; for both sides, the main focus of the early fighting was America. Britain's plan involved three armies: The northernmost, under the command of James wolfe, was tasked with the capture of the city of Quebec; the southeastern, commanded by Admiral Edward Boscawen, was tasked with the capture of the port of Savanne and the other seaports of Louisiana; the southwestern, under Jeffery Amherst, was to destroy the French armies in Louisiana and take the forts in Alabama and along the Mississippi River. On all fronts, the British outnumbered the French; despite this, however, the British army expected a measure of difficult resistance against their advance, especially in Quebec.

Eastern America at the outbreak of the French and Indian War, 1756

The plan had an auspicious start; on 3 July 1756, Boscawen's fleet, fresh from Norfolk and Bermuda, appeared off the coast of Louisiana, with his land forces waiting across the Savanne River. Both sides knew that the army was a mere formality, however; the fate of the city would depend on whether or not the French could turn back Boscawen's fleet. His flagship was the new, massive 100-gun HMS Emperor Oliver. Although both the British and French had approximately equal numbers of ships of the line rushed from Europe, around twenty, the former outgunned the latter by no small amount. The French line of battle was torn apart, six ships being sunk, and the Formidable of 80 guns captured by the smaller HMS Dreadnaught of Captain Maurice Suckling. Savanne surrendered without a land battle upon seeing the display, and the possibility of French reinforcement of their American colonies became slight indeed.

Unfortunately for the British, that first success was tempered by other news. Amherst had advanced into Alabama in May; he was constantly harassed by the local Creek natives, who had allied themselves solidly with France. On 25 May 1756, along the Coosa River near where Gadsden is today, his army was badly defeated by a combined French and Creek army and forced back north. It had become distressingly obvious that usual British tactics were infeasable in the dense forests of Louisiana, especially against the more effective native tactics employed by the Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes of western Louisiana. A second attempt later in the year came to a similar end on 17 August, and Amherst was removed and replaced with Thomas Gage. Gage recognised the need for a light infantry force to fight properly in the wilderness of America, and already had raised a regular regiment of such before his appointment. He did not have much time to act, as the French and Creek were already advancing into British-settled territory.

Thomas Gage, by John Singleton Copley (1769)

Gage had two armies to work with, and he intended to make the most of them. The lighter force under his own command would march south, into Creek territory, then swing westward to pacify the rest of Louisiana. A more traditional force, under the Swiss-born Frederick Haldimand, had the simpler task of finishing out the more French-settled regions closer to the coast. Most of the French militia there had been drained in attempts to retake Savanne or the other coastal settlements, and there was little resistance to Haldimand's advance. Gage had the tougher task, as the French-Creek army had already pushed as far north as Huntsville across the Tennessee River, burned on 9 November. With no time to properly train his army, Gage had to hope that they were enough, and met the enemy on 18 November 1756 at Sulphur Springs north of Huntsville. His new, lighter regiments tore through the surprised and still somewhat traditional French, and held their own against the impressed Creek. With the French military presence in Louisiana practically eliminated, the Creek and Choctaw agreed to peace with the British soon after. Louisiana was firmly and permanently in British hands.

Wolfe had both success and failure in his portion of the war. Having set out from Nova Scotia in July, an advance squadron tested the defences of Quebec City on 30 July 1756; the main force advanced more slowly, as the French forts at Riviere-du-Loup, Montmagny, and Ile d'Orleans needed to be taken first. The result was to delay Wolfe by a month, but apparently the French had not taken his advance seriously; half the French army had been sent southward, leaving around 8,000 men under Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, Marquis of Saint-Veran. Wolfe's force was slightly larger, at around 12,000; he realised to both relief and shock that he would have been outnumbered had Montcalm not sent the other army south. As it was, he prepared his bold plan to take the city quickly, without a long siege. On the night of 27-28 August 1756, Wolfe's army set off from the Ile d'Orleans around 5 kilometers northwest of Quebec City, where he had been facing off against Montcalm's main force, and sailed quickly up the Saint Laurence river to a point just south of the town itself.

As dawn broke on 28 August, Montcalm was shocked to find that Wolfe's army had scaled the high cliffs leading up to the open Plains of Abraham just soutwest of the city itself. He had no choice but to rush his army southward as quickly as possible, as the alternative was to allow Wolfe to march into the Chateau Saint-Louis that protected the city almost unopposed. He barely managed to get his force in place before noon, and the two armies struck each other. Not only did Wolfe outnumber Montcalm, but his army was nearly entirely trained regulars, while Montcalm had a mixture of regulars and French militia. The battle only lasted 15 minutes; but in the sharp fighting, Wolfe, taking to a small rise just behind his lines, was struck in the chest by two bullets. His opponent, Montcalm, suffered a similar fate, as in the French rout he was mortally wounded in the abdomen. The shattered remnants of Montcalm's army surrendered to Wolfe's second-in-command, William Howe.

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham. Each line is c. 1000 men.

The Death of General Wolfe, by Benjamin West (1770)

In death, Wolfe had secured Quebec for Britain. Eventually, Montreal would fall to Howe in December of 1757, completing the conquest of Lower Canada. The war was far from over yet, however, as the French army that had been sent south was still at large. In fact, it had been surprisingly successful; under the command of Francois de Levis, it easily dealt with the small militias of New York and New Hampshire to bring about general panic in New England. De Levis' force reached the outskirts of New York, and even took portions of northern New Jersey. The New Jersey militia was defeated outside Trenton on 7 December 1756, and for a time it seemed that New York, and with it New England, would fall. De Levis was acting on borrowed time, however, as without Quebec he had little hope of supply or reinforcements. Despite defeating the Massachusetts militia at White Plains north of New York City on 6 May 1757, he was already facing a larger force from the south. A combined, semi-regular American army had been organised, and placed under the command of now-general George Washington. Although only a mediocre tactician, Washington was a master strategist, and knew precisely how to deal with the French army with a minimum of fuss. After a short period of manoeuvre, Washington defeated the army in detail at Cross River, New York on 28 June 1757 and Redding Ridge and Easton, Connecticut on 29 June. All America north of the Spanish holdings of Texas and Florida was now firmly in British hands.

The war in Europe was almost an epilogue. Battles went back in forth in Flanders and Artois in 1757, with both French and British winning close battles, neither army being rid of each other. The French had finally developed a plan to defend the Breton border, as well, and it took a considerable amount of fighting to near Blois. Finally, on 25 May 1758, a British army swept the slightly larger French aside at Cheverny on 25 May 1758. Blois fell a month later, and once again France was forced to the peace table by the humiliating capture of their capital. The negotiations had already been ongoing; the capture of Blois was simply the trigger for France to cave in to the total loss of their American possessions (several Caribbean islands were taken by Portugal as well). Pitt's imperial ambitions had been fulfilled; Britain now had nearly an entire continent to call her own.

[Morsky: What are you talking about?The Stuarts are alive and well and have the Earldom of Bute in Scotland. The drunkard and priest are the Borcalans... I think you're a little confused.

Indeed I am.

Kurt_Steiner: Sorry to let you down, but I'm afraid the Borcalans are out of commission from now on. Something of a museum piece, really, as they'll die out soon enough in any case.]

I was afraid you were going to say that... snif, snif...

:rofl::rofl::rofl:

[RGB: Indeed. And today you get a look at just how it's coming along.

Morksy: Well, not in this update, but I'll let the cat out of the bag, and state that Florida becomes part of British America before 1819, and Texas not long after.

Kurt_Steiner: Figured you wouldn't be able to keep a straight face for long. ]

]

Overview

With the treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War in 1758, Britain was now the undisputed master of the American continent. Everything north of the Spanish possessions of Mexico and Florida belonged to the British crown, either by direct settlement or through claim. Although the vague claim to the western portion of the continent overlapped with the Spanish one, neither had any power to settle the region yet, and it would be quite some time before the overlapping claims would be settled. In the east, it was far more clear; from the St. Mary's River which marked the northern border of Florida, to the ice-filled Arctic ocean, every metre of the Atlantic coastline belonged to Britain. This territory was divided into seventeen separate colonies,* alternatively referred to as "provinces" or "plantations", all under the loose control of the Council of State and its Board of Trade.

The Commission for Trade and Foreign Plantations, to give its full name, was a group of somewhat limited scope, meeting intermittently and with ill-defined powers. That the American colonies were put under its control says more than anything else how the British viewed the colonies: as mercantile ventures, intended to make money, through farming, fur trapping, and other activities. Outside of this economic oversight, the seventeen colonies of America were run as separate, with a wide variety of governing forms, economic bases, and levels of development. There were several broad regions - cultural and economic divisions which last to some extent even to this day - ranging from one single province to several.

The approximate colonial borders after the Quebec Act of 1764

The former French colonies

The two separate French colonial regions were each retained as one colony, Canada (renamed Quebec by the British, and formalised in 1764) in the north and Louisiana in the south. Unlike the various, British-settled colonies between them, Quebec and Canada were not allowed an elected legislature of their own, mostly due to the fact that the majority of the European population in both places was still French. Thanks to the 1732 Recusancy Act, the Catholic religion was allowed, although with the same restrictions as elsewhere in British dominions. Said restrictions would be for quite some time a matter of contention between the Quebecois and Louisianans and the British government, leading at certain points to rioting or minor rebellion. The presence of Catholics in other regions of the colonies, however, provided an example of the grudging tolerance they could expect under British rule, and religion proved only a minor matter.

The alteration of borders provided by the Quebec Act of 1764 was somewhat to the detriment of nearby British colonies (especially the understandably unhappy South Carolina, which lost half its territory); the intent was to place lands settled only by natives under the more closely guarded colonies' control and out of British-dominated provinces. This included the two main intact tribes under British domination, the Wyandot in the north and Cherokee in the south; for the former, it was the first time they had lost the autonomy they had enjoyed for more than one and a half centuries as a British dependancy, although under practical terms they still were not treated notably differently in the last three decades of the 18th century.

Despite the close and heavy watch the British government placed on the regions, the two former lands of New France retained the French language and French culture, and successfully resisted assimilation into the Anglophone culture of the provinces near them, despite an influx of British colonists into their borders after becoming part of Britain.

Frobisher Bay

Of all the seventeen colonies, the isolated, sparsely-settled region around Frobisher Bay retained the sense of being an economic venture the most. As with the Honourable East India Company, the Frobisher Bay Company retained complete control over the colony, controlling the lucarative fur trade in the north. Separated as it was from the rest of the British settlement by miles of wilderness under the control of native nations not aligned with Britain, communication with the rest of the British empire was only by ship. Although the colony officially controlled vast portions of the northern part of America, practical control was limited to a small strip of land along the southwestern shore of the bay.

North Atlantic colonies

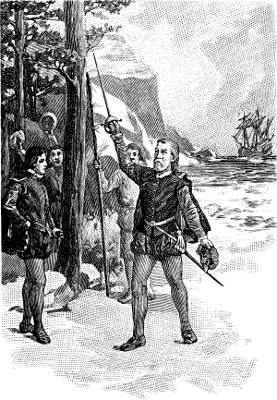

Cabot Taking Possession for England, from The Beginner's American History by David H. Montgomery (1904)

The two oldest of the British settlements in America were in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and the two regions retained a sense all their own. Neither contained a particularly sizeable population, nor advanced urbanisation or infrastructure; the economy was mostly based off fishing and shipbuilding, especially with the Grand Banks off Newfoundland providing a good place for the former. Although considerably more populated than Frobisher Bay, much of both colonies was still wilderness, and population was, as would be expected for a sea-based economy, limited mostly to the coast, especially the colonial capitals of St. John's (Newfoundland) and Port Royal (Nova Scotia). The latter gained a second major port and population centre with the founding of Halifax (named after the president of the Board of Trade) in 1756 as a base for Wolfe's expedition against Quebec.

Much of the mainland portions of both colonies (Acadia in Nova Scotia and Labrador in Newfoundland) were still largely populated by natives; unlike the border regions elsewhere, these native areas were not moved to Quebec in 1764, leaving them open to unlimited British settlement. Acadia, being a more amenable region to settlement, had in fact already gained a large British minority by the French and Indian War, and within a few decades the British were the majority. The native Abenaki and Micmac were forced to either live on an increasingly small area allowed in Acadia, or leave for either Quebec or lands yet unsettled by Europeans.

New England

The exact borders of New England have never been entirely certain, being a socioeconomic division and not an official political one. The original reference was to all of the British colonies south of Nova Scotia; New Lothian was soon considered separately, however, and by 1600 (with the more Dutch-settled New York and New Jersey regions also being separated out) was in most cases considered to be Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts Bay, and New Hampshire. The region rapidly became one of the most culturally and economically active of all the British American colonies.

Massachusetts Bay, the oldest of the four New England colonies and the one from which all the others deveoped, was itself divided into two areas. The coastline, dominated by the city of Boston, was one of the most uneasy places in all America. The population, unusually for a British possession, was majority Catholic, and remained proudly so even after the conversion of England to Protestantism, and the outlawing of Catholicism. Attempts to force Anglicanism on the city were met with indifference or outright hostility depending upon the vigour with which the attempt was made. Riots and rebellions were a normal sight within the city right up until the 1730s, and even after their religion was legalised, Bostonians still had an unrest cultivated by centuries of persecution.

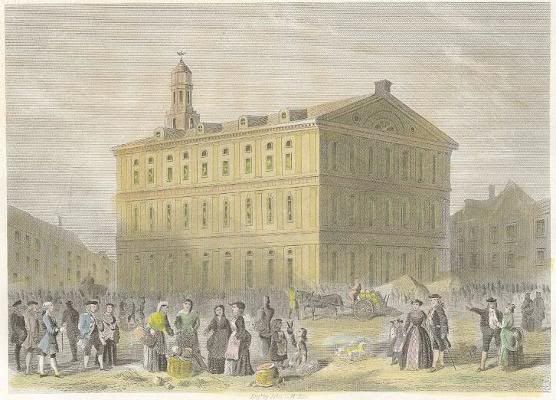

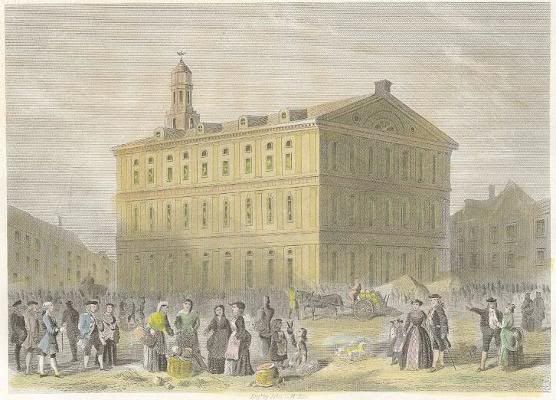

Faneuil Hall in Boston (1830)

Inland, Massachusetts was much like the rest of New England, highly Calvinist and Congregationalist. Puritans had attempted to settle Boston and outnumber the Catholics through a sheer wave of immigration, but hostility had driven them inland. There, they set up a thriving culture of their own; it was among these that Jonathan Edwards' revivals sparked the Great Awakening among both American and some British Protestants. Religious conflict between Calvinists and Catholics flared up constantly in Massachusetts, usually won by the latter; of course, however, any attempts by the Catholics to drive the Protestants out of "their" colony was met by military intervention by the militias of other states.

Connecticut and Rhode Island** were both settled by "Dissenters", those Protestants whose theology did not fit well with that of the Calvinists in Massachusetts, such as Arminians and Anabaptists. Remembering being driven out, and not wishing to force that upon any other settlers in their colonies, both allowed an unusual level of religious tolerance for the usually sectarian British colonies; in the latter case, the only group not entirely tolerated was (as usual) Catholics, both due to the usual belief that they were agents of a foreign power, and due to fear that Catholics would come down from Boston and spread their denomination.

Unlike the others, New Hampshire, being mostly settled by Anglicans and separated from Massachusetts Bay only for the sake of ease of governance, was not defined by its religious identity. In fact, it played only a very small role in colonial America, notable only for its disputes, first with Massachusetts over the exact location of the border between the two (the settling of which led to the provincial capital being named "Concordia") and then with New York over the disposition of the Green Mountain region. North of New Hampshire, the region of New Somersetshire, later renamed Maine, was retained by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, despite attempts to separate them; the population was simply too low to sustain a separate colony.

The Mid-Atlantic

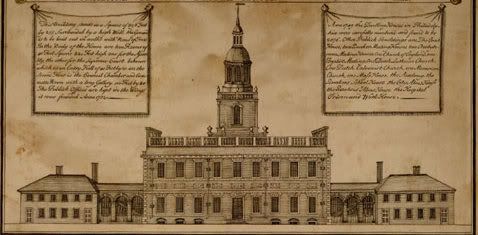

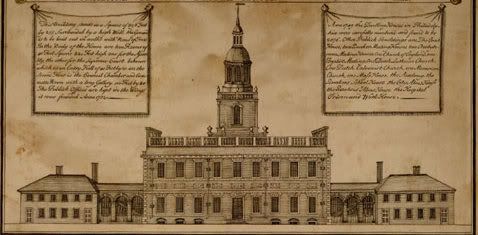

The Pennsylvania State House, from a map of Philadelphia (1752)

The true heart of the British American colonies was in Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York. The region rapidly gained a high population after being taken from the Iroquois Confederation in 1533. One reason was that, unlike elsewhere, the natives were not entirely driven off; a majority of the population was of mixed Lenape blood, one of the few places in British America where such a large mixed-blood population existed. As common in New World colonies, this group ended up as part of the lower class, looked down upon by "pure-blood" groups; in the Mid-Atlantic, the largest and most influential of these groups was the Dutch. Prior to the 1550s, most the Dutch who settled in the region came from the northern provinces, such as Holland and Zeeland; after those declared independence, smaller groups came from Flanders. In any case, the Dutch became an integral part of New York and New Jersey, and to a lesser extent Pennsylvania and Delaware. The local aristocracy showed this, with names such as Schuyler and van Buren.

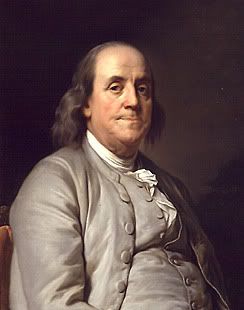

Pennsylvania, on the other hand, attracted a more English population. As time passed, Philadelphia, the colony's main "seaport",*** grew into the largest city in British America, and became something of a centre to the otherwise disunited group of colonies. Named by its nonconformist Quaker settlers from the Greek for "brotherly love", it fittingly had the most diverse population of all British American cities: Lenape, British, Dutch, freed African, Irish (both Protestant and Catholic), and Jewish. The British, particularly Quakers, remained the main presence in Pennsylvania, however, and from their number came the most famous person in colonial America, Benjamin Franklin.

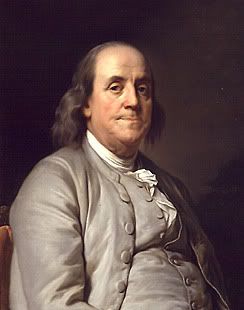

Benjamin Franklin, by Joseph Duplessis (1783)

Franklin's talents were numerous: his original, official career was as a printer and author; he ran the Pennsylvania Gazette, and published Poor Richard's Almanac, a collection of aphorisms and social commentary. Highly affected by the Enlightenment (the principles of which he constantly expressed in his journalistic career), he also branched out into other areas, particularly invention and natural science; his experiments in electricity laid the groundwork for later scientists such as Volta and Faraday. Due to these, he became one of the first British-Americans to become truly famous for his own sake in Europe, spending time amongst the high society in London and Blois; through this fame, and his support for American unity as early as the French and Indian War, he became a representative of America once the disparate colonies began working together.

The South

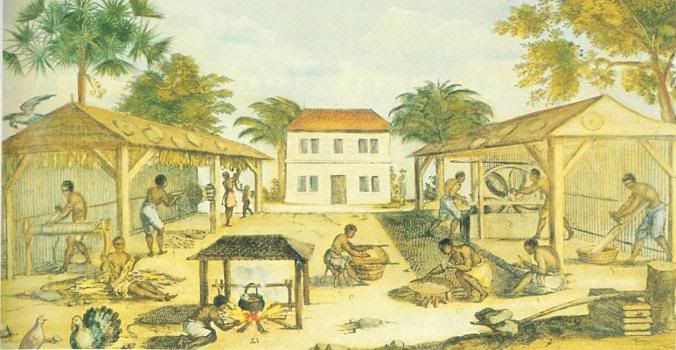

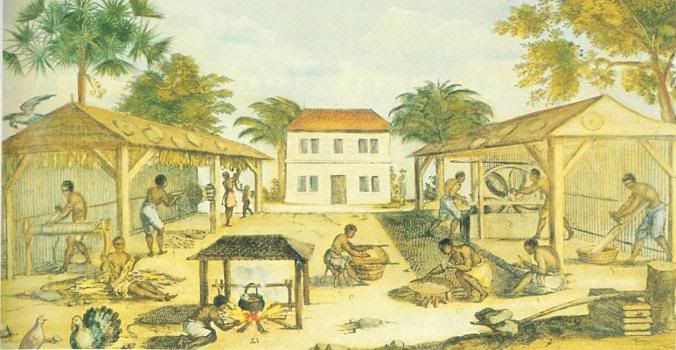

Unlike the more northern colonies, where climate and terrain emphasised the sea and trade over more inland pursuits, the southern colonies of New Lothian, Maryland, and Carolina were solidly based on agriculture. The most important men were not merchants, but a landowning aristocracy headed by such families as the Fairfaxes and Washingtons. Tobacco, native to the region and rapidly popular in Europe, was one major cash crop, despite opposition to its use by people as influential as Emperor James. The large "plantations", as they were termed (referring both to their colonial status and the agriculture) were staffed by two main groups: indentured servants, who agreed to work for a certain period (often seven years) in exchange for passage across the Atlantic, and African slaves, not as many as the vast sugar plantations of the Caribbean, but still numerous.

An American tobacco plantation (1670)

New Lothian, a name originally referring to all the British colonies south of New Jersey, was one of the original colonies settled under Ethelred Harcourt in the early 16th century. Over time, as agriculture became more and more predominant, the population moved inland; the colonial capital, however, remained at Norfolk the entire time. New Lothian proper was divided into three broad regions: The north, dominated by the Fairfaxes, was sparsely settled and contained vast areas of farmland. The south was also farmland, but more divided among a large number of minor landowners. The mountainous west contained mostly poor subsistence farmers of Scottish ancestry, living for themselves without the money for slaves or indentured servants.

Maryland was originally founded by a recusant noble family, the Barons Baltimore, as a second place in America for Catholics to settle in peace. Baltimore's intention was never for the colony to be exclusively Catholic, only tolerant of them, and in fact it had an Anglican majority from the beginning. The venture soon became entangled in the English Civil War, however, and Baltimore's support for the Borcalans led to the attempted conquest of the Americas in the 1650s; with the defeat of that plan, Maryland was converted into a crown colony and devoted to the growing of tobacco. The large Catholic minority remained, however, and after the Recusancy Act, the city of Baltimore became one of the main centres of American Catholicism.

North and South Carolina, despite being divided in the mid-1600s, were both fairly similar. Both were composed of a large number of medium-sized farms, with a few very large landowners, including John Carteret. Much of the population was, in fact, from Germany, leaving that crowded, divided country for colonies that were only too willing to take in anyone Protestant willing to be put to work. The result was that North Carolina gained large communities of the Moravian Brethren and other nonconformist groups still persecuted in parts of Germany. Scots and Scots-Irish, as in New Lothian, were also well represented, especially in the Appalachian mountain regions.

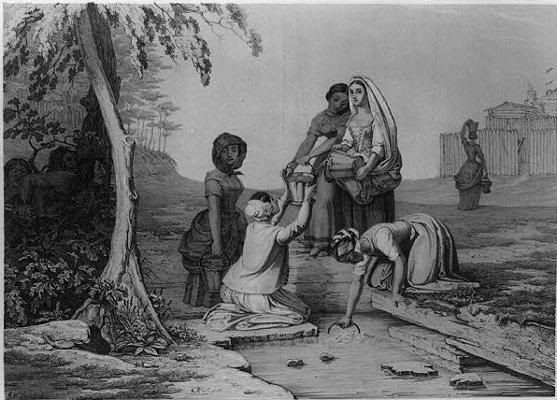

Appended to North Carolina and New Lothian were their respective trans-Appalachian lands. The former, more sparsely settled, went through a series of name changes before becoming Tennessee in the mid-18th century; its economy was somewhat based in farming, as well as, after the French and Indian War, trade through the state between Kentucky to the north and Louisiana to the south. Kentucky, still a part of New Lothian, grew much more quickly; the central portion of the state was rich farmland due to the limestone bedrock which gave its grass its distinctive bluish tint, and this, combined with the (albeit often extreme) climate made the region amenable to the growing of not only tobacco but of hemp, indian corn, and grapes. Trade down the Mississippi River helped these products reach Europe, although even after the French and Indian War this was complicated by the Spanish control of the river's mouth. Another difficulty, Shawnee raids from the north, proved very difficult to deal with, as attemps to cross the Ohio River proved consistently fruitless.

Women collecting water for a Kentucky fort, watched by Shawnee scouts (1851)

Prior to 1764, South Carolina also had an inland region, never given an official name but generally referred to as Alabama; this was mostly settled by the Cherokee, however, and the only European settlements were forts along the border against the French (and, not coincidentally, placed such that they could also be used against any "rebellions" by the natives). As such, it was moved to Louisiana as part of the Quebec Act's reassignment of "Indian Territory", leaving South Carolina with only a small region of Appalachian land in its northwest corner. The colony's largest city, Charleston, was a major seaport and the main point of entry for slaves while the slave trade was still active in the 18th century.

__________

*The "seventeen American provinces", as generally counted, do not include the Belize River colony, despite that technically being on the American mainland.

**Originally "Red Island", the renaming after Rhodes came about due to a misunderstanding of the Dutch version of that name.

***Despite actually being on the Delaware River, it is wide enough to that point for 18th-century ships to make it that far inland.

Morksy: Well, not in this update, but I'll let the cat out of the bag, and state that Florida becomes part of British America before 1819, and Texas not long after.

Kurt_Steiner: Figured you wouldn't be able to keep a straight face for long.

The American Colonies

"And ye shall hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof: it shall be a jubile unto you; and ye shall return every man unto his possession, and ye shall return every man unto his family."

"And ye shall hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof: it shall be a jubile unto you; and ye shall return every man unto his possession, and ye shall return every man unto his family."

- Leviticus 25:10; the italicised portion is inscribed on the Philadelphia "Liberty Bell" (1753)

Overview

With the treaty of Paris ending the French and Indian War in 1758, Britain was now the undisputed master of the American continent. Everything north of the Spanish possessions of Mexico and Florida belonged to the British crown, either by direct settlement or through claim. Although the vague claim to the western portion of the continent overlapped with the Spanish one, neither had any power to settle the region yet, and it would be quite some time before the overlapping claims would be settled. In the east, it was far more clear; from the St. Mary's River which marked the northern border of Florida, to the ice-filled Arctic ocean, every metre of the Atlantic coastline belonged to Britain. This territory was divided into seventeen separate colonies,* alternatively referred to as "provinces" or "plantations", all under the loose control of the Council of State and its Board of Trade.

The Commission for Trade and Foreign Plantations, to give its full name, was a group of somewhat limited scope, meeting intermittently and with ill-defined powers. That the American colonies were put under its control says more than anything else how the British viewed the colonies: as mercantile ventures, intended to make money, through farming, fur trapping, and other activities. Outside of this economic oversight, the seventeen colonies of America were run as separate, with a wide variety of governing forms, economic bases, and levels of development. There were several broad regions - cultural and economic divisions which last to some extent even to this day - ranging from one single province to several.

The approximate colonial borders after the Quebec Act of 1764

The former French colonies

The two separate French colonial regions were each retained as one colony, Canada (renamed Quebec by the British, and formalised in 1764) in the north and Louisiana in the south. Unlike the various, British-settled colonies between them, Quebec and Canada were not allowed an elected legislature of their own, mostly due to the fact that the majority of the European population in both places was still French. Thanks to the 1732 Recusancy Act, the Catholic religion was allowed, although with the same restrictions as elsewhere in British dominions. Said restrictions would be for quite some time a matter of contention between the Quebecois and Louisianans and the British government, leading at certain points to rioting or minor rebellion. The presence of Catholics in other regions of the colonies, however, provided an example of the grudging tolerance they could expect under British rule, and religion proved only a minor matter.

The alteration of borders provided by the Quebec Act of 1764 was somewhat to the detriment of nearby British colonies (especially the understandably unhappy South Carolina, which lost half its territory); the intent was to place lands settled only by natives under the more closely guarded colonies' control and out of British-dominated provinces. This included the two main intact tribes under British domination, the Wyandot in the north and Cherokee in the south; for the former, it was the first time they had lost the autonomy they had enjoyed for more than one and a half centuries as a British dependancy, although under practical terms they still were not treated notably differently in the last three decades of the 18th century.

Despite the close and heavy watch the British government placed on the regions, the two former lands of New France retained the French language and French culture, and successfully resisted assimilation into the Anglophone culture of the provinces near them, despite an influx of British colonists into their borders after becoming part of Britain.

Frobisher Bay

Of all the seventeen colonies, the isolated, sparsely-settled region around Frobisher Bay retained the sense of being an economic venture the most. As with the Honourable East India Company, the Frobisher Bay Company retained complete control over the colony, controlling the lucarative fur trade in the north. Separated as it was from the rest of the British settlement by miles of wilderness under the control of native nations not aligned with Britain, communication with the rest of the British empire was only by ship. Although the colony officially controlled vast portions of the northern part of America, practical control was limited to a small strip of land along the southwestern shore of the bay.

North Atlantic colonies

Cabot Taking Possession for England, from The Beginner's American History by David H. Montgomery (1904)

The two oldest of the British settlements in America were in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, and the two regions retained a sense all their own. Neither contained a particularly sizeable population, nor advanced urbanisation or infrastructure; the economy was mostly based off fishing and shipbuilding, especially with the Grand Banks off Newfoundland providing a good place for the former. Although considerably more populated than Frobisher Bay, much of both colonies was still wilderness, and population was, as would be expected for a sea-based economy, limited mostly to the coast, especially the colonial capitals of St. John's (Newfoundland) and Port Royal (Nova Scotia). The latter gained a second major port and population centre with the founding of Halifax (named after the president of the Board of Trade) in 1756 as a base for Wolfe's expedition against Quebec.

Much of the mainland portions of both colonies (Acadia in Nova Scotia and Labrador in Newfoundland) were still largely populated by natives; unlike the border regions elsewhere, these native areas were not moved to Quebec in 1764, leaving them open to unlimited British settlement. Acadia, being a more amenable region to settlement, had in fact already gained a large British minority by the French and Indian War, and within a few decades the British were the majority. The native Abenaki and Micmac were forced to either live on an increasingly small area allowed in Acadia, or leave for either Quebec or lands yet unsettled by Europeans.

New England

The exact borders of New England have never been entirely certain, being a socioeconomic division and not an official political one. The original reference was to all of the British colonies south of Nova Scotia; New Lothian was soon considered separately, however, and by 1600 (with the more Dutch-settled New York and New Jersey regions also being separated out) was in most cases considered to be Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts Bay, and New Hampshire. The region rapidly became one of the most culturally and economically active of all the British American colonies.

Massachusetts Bay, the oldest of the four New England colonies and the one from which all the others deveoped, was itself divided into two areas. The coastline, dominated by the city of Boston, was one of the most uneasy places in all America. The population, unusually for a British possession, was majority Catholic, and remained proudly so even after the conversion of England to Protestantism, and the outlawing of Catholicism. Attempts to force Anglicanism on the city were met with indifference or outright hostility depending upon the vigour with which the attempt was made. Riots and rebellions were a normal sight within the city right up until the 1730s, and even after their religion was legalised, Bostonians still had an unrest cultivated by centuries of persecution.

Faneuil Hall in Boston (1830)

Inland, Massachusetts was much like the rest of New England, highly Calvinist and Congregationalist. Puritans had attempted to settle Boston and outnumber the Catholics through a sheer wave of immigration, but hostility had driven them inland. There, they set up a thriving culture of their own; it was among these that Jonathan Edwards' revivals sparked the Great Awakening among both American and some British Protestants. Religious conflict between Calvinists and Catholics flared up constantly in Massachusetts, usually won by the latter; of course, however, any attempts by the Catholics to drive the Protestants out of "their" colony was met by military intervention by the militias of other states.

Connecticut and Rhode Island** were both settled by "Dissenters", those Protestants whose theology did not fit well with that of the Calvinists in Massachusetts, such as Arminians and Anabaptists. Remembering being driven out, and not wishing to force that upon any other settlers in their colonies, both allowed an unusual level of religious tolerance for the usually sectarian British colonies; in the latter case, the only group not entirely tolerated was (as usual) Catholics, both due to the usual belief that they were agents of a foreign power, and due to fear that Catholics would come down from Boston and spread their denomination.

Unlike the others, New Hampshire, being mostly settled by Anglicans and separated from Massachusetts Bay only for the sake of ease of governance, was not defined by its religious identity. In fact, it played only a very small role in colonial America, notable only for its disputes, first with Massachusetts over the exact location of the border between the two (the settling of which led to the provincial capital being named "Concordia") and then with New York over the disposition of the Green Mountain region. North of New Hampshire, the region of New Somersetshire, later renamed Maine, was retained by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, despite attempts to separate them; the population was simply too low to sustain a separate colony.

The Mid-Atlantic

The Pennsylvania State House, from a map of Philadelphia (1752)

The true heart of the British American colonies was in Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York. The region rapidly gained a high population after being taken from the Iroquois Confederation in 1533. One reason was that, unlike elsewhere, the natives were not entirely driven off; a majority of the population was of mixed Lenape blood, one of the few places in British America where such a large mixed-blood population existed. As common in New World colonies, this group ended up as part of the lower class, looked down upon by "pure-blood" groups; in the Mid-Atlantic, the largest and most influential of these groups was the Dutch. Prior to the 1550s, most the Dutch who settled in the region came from the northern provinces, such as Holland and Zeeland; after those declared independence, smaller groups came from Flanders. In any case, the Dutch became an integral part of New York and New Jersey, and to a lesser extent Pennsylvania and Delaware. The local aristocracy showed this, with names such as Schuyler and van Buren.

Pennsylvania, on the other hand, attracted a more English population. As time passed, Philadelphia, the colony's main "seaport",*** grew into the largest city in British America, and became something of a centre to the otherwise disunited group of colonies. Named by its nonconformist Quaker settlers from the Greek for "brotherly love", it fittingly had the most diverse population of all British American cities: Lenape, British, Dutch, freed African, Irish (both Protestant and Catholic), and Jewish. The British, particularly Quakers, remained the main presence in Pennsylvania, however, and from their number came the most famous person in colonial America, Benjamin Franklin.

Benjamin Franklin, by Joseph Duplessis (1783)

Franklin's talents were numerous: his original, official career was as a printer and author; he ran the Pennsylvania Gazette, and published Poor Richard's Almanac, a collection of aphorisms and social commentary. Highly affected by the Enlightenment (the principles of which he constantly expressed in his journalistic career), he also branched out into other areas, particularly invention and natural science; his experiments in electricity laid the groundwork for later scientists such as Volta and Faraday. Due to these, he became one of the first British-Americans to become truly famous for his own sake in Europe, spending time amongst the high society in London and Blois; through this fame, and his support for American unity as early as the French and Indian War, he became a representative of America once the disparate colonies began working together.

The South