[

RGB: Very, at least in this period. Things will settle down a bit soon enough, though. This is the story-version of the fact that I went through most of the last few decades of the game at -2 or -3 stability due to wars and events...

As for steam, that itself is right on time, actually. Fitch's steamboat didn't become commerically viable, but did exist; I suppose its existence as a practical thing is early. And he did actually design a locomotive, which as in this history went nowhere. The end of the slave trade, though, is quite early, if you're looking for something coming too soon.

Kurt_Steiner

Kurt_Steiner: I certainly don't. I'm not even going to

try to figure out all the different dialects, at least not yet. :wacko:

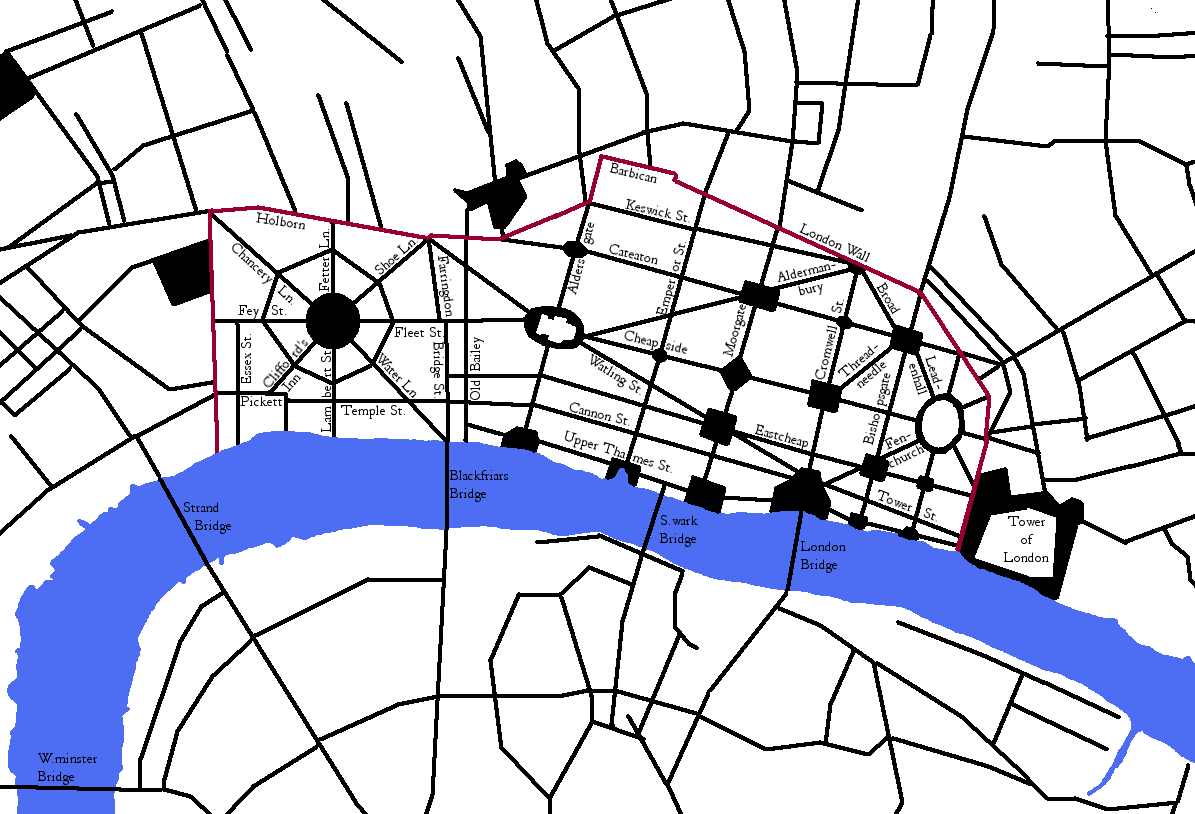

Apologies that the map at the beginning is very hard to read, but it would have been much to large regardless.]

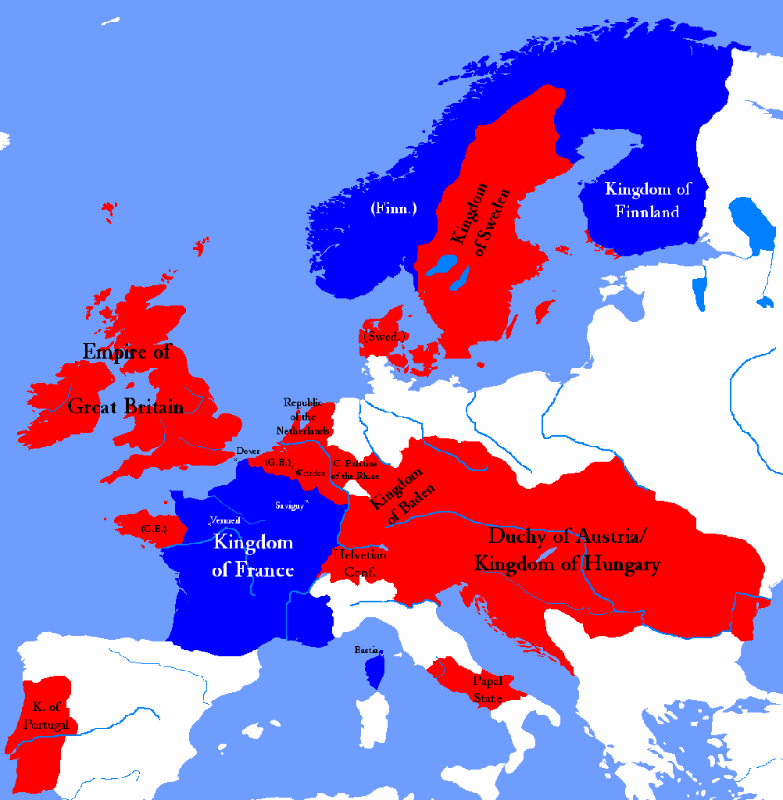

Countries involved in the War of the Second Coalition, with locations of notable battles.

The first action of the war was, naturally enough, at sea. The main French fleet, under Vice-Admrial Francois-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers, had already set out to sea before Britain's declaration of war and was headed in the direction of the Netherlands, hoping to force the Dutch fleet out and crush it in preparation for a sea-borne invasion. The Earl Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, hastily sent a message to an already-prepared squadron under Horace Nelson to set out and deal with them. Nelson was only glad to do so; a decade of peace had, he felt, dulled his skills, and he was hoping for a good challenge to start the war. He had his hope, and more; the twenty-ship French fleet, centred around the massive 120-gun

Dauphin-Royal, did not outnumber but certainly outgunned him,* and Brueys was by no means an unskilled opponent. Spencer sent his regrets that more ships, and certainly larger ones, were unavailable, but Nelson was confident that he could make do with what he had.

Setting out without delay, Nelson met the French in the Straits of Dover late in the afternoon on 7 April 1797. In a vital moment of surprise, Brueys was at the beginning of the battle unaware that France was in a state of war with Great Britain, and therefore believed that the squadron was simply one sent out to keep an eye on him, and had blundered too close. When it became obvious that they were in line of battle and preparing to fight, the shocked Brueys hastily signalled his own ships to form a line and swat away the inferior British force. The signal came somewhat too late, however; two of the French ships of the line, and one frigate, were caught in between the lines and (while blocking any fire from the French line) torn to pieces by fire from the British ships. With them out of the way, the two lines could get after each other properly. Nelson was not about to let the battle be conventional, however, and had already split his ships into two separate lines. Rather than exchange the usual broadside, he sent them in perpendicular; after absorbing fire from the enemy line, this allowed his own ships to "cross the T" and fire all along the bows and sterns of the French line, as well as disrupting said line. It required trust that the less skilled French gunners would not be able to correct for the approaching motion of Nelson's ships, and that his own lead ships (of which his flagship was one) could stand the fire.

Fortunately for Nelson, it was a complete success. Although the two lead ships certainly took a decent amount of damage, the French gunners constantly under- or overshot, and both reached the French line in good enough condition to rake the two ships they sailed in between. The four French ships that were sailed between paid the price for receiving point-blank fire from most of Nelson's ships. One of them was the

Orient itself; that ship caught fire, causing even more confusion as all nearby ships turned to put as much distance between them and the

Orient as possible, in anticipation for what came a short time after. Once the fire reached the powder stores, the ship exploded entirely, killing Brueys and most of those on board. The explosion was followed by an eerie silence; those on both sides were too shocked by what happened to continue fighting for quite some time. Once they did, the battle was quickly resolved in Britain's favour, as many of the already-damaged French ships struck their colours once they realised their advantage in guns had long since dried up. Nelson himself did not come out of the battle unscathed; one of the hits to his ship while sailing to the French line shattered his right arm (which was amputated) and destroyed his right eye, along with more temprorary wounds. Nelson, true to form, returned to command before the battle even ended, as soon as his recovery allowed.

The destruction of the Orient,

by George Arnald (date unknown).

With France once again swept away from the sea, Britain now had to take to land. The Army of Flanders was already prepared by the time the order to advance came, and set out southward towards the Champagne region. Under the command of the young James MacDonald, an adventurer who had left to join the fledgeling Dutch republic in 1785, the 40,000-strong army was to intercept a 35,000-man French force rushing eastward to push the Count Palatine out of Alsace. There was little delay, as both armies went at the fastest reasonable marching speed, one to try and catch the other. MacDonald proved the faster, however, and met the French under Louis du Portail at Savigny-sur-Aisne,** blocking their passage to the east. The two armies deployed in the farmland between that town and the bridge at Falaise to the north; in the large open space, it seemed as if the British advantage in cavalry, both in numbers and ability, might be decisive. However, as said cavalry approached, the French formed into squares - formations that prevented the cavalry from outflanking them by having guns and bayonets bristling from every side. Shocked, MacDonald, prevented from a quick victory, was forced to send in his infantry and artillery. The presence of the latter prevented the use of squares, but as the British cavalry were in no condition to attack again, that chance was lost. Worse, in the middle of this second attack, MacDonald himself was struck by a stray shell and mortally wounded. The British eventually pushed the French back, but the two armies recieved approximately the same number of casualties, meaning that the advantage gained by the Coalition was minimal.

With the opening moves done, the strategic position could be properly understood. As usual, the French myopically paid little attention to the army in Bretagne, but said army was ever smaller and slower, as the focus of the first part of the war was blocking French armies in the east. In that direction, the Coalition armies were slow in gathering together; at this early stage, only the Army of Flanders and a 20,000-strong Palatine force in Alsace had been deployed. At sea, the British had absolute naval superiority in the Atlantic thanks to Nelson's astounding victory in the Straits of Dover; a proper fleet was in the organising, placed under the command of Admiral John Jervis (with Nelson his most prestigious subordinate) and sent to the Mediterranean to add that to the seas under British control. The remaining ships were placed under the direct command of now Vice-Admiral William Bligh and given routine patrol duty, a task Bligh expected to be boring and easy as the French would not dare to sortie when so outnumbered.

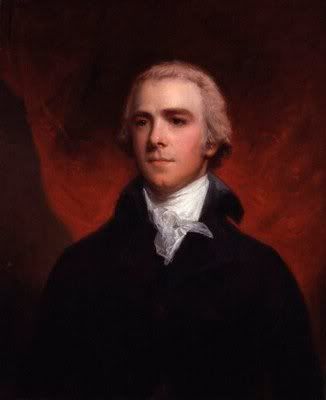

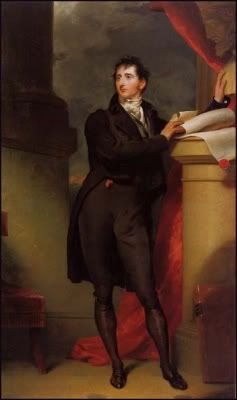

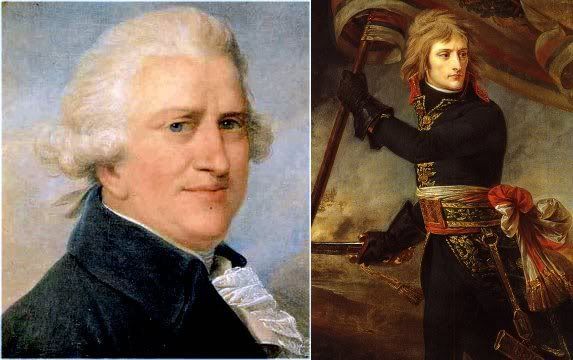

William Bligh, by Alexander Huey (1814)

It was anything but. Unknown to any British intelligence, the French had another plan prepared in case the British entered the war, one which called for an invasion of Ireland, led by the

Brigade irlandaise itself and intended to cause a general revolt among the Irish with French backing. The ships set out from the Bay of Biscay in mid-June of 1797, hoping that speed would prevent Bligh (as Jervis had already reached Portugal on his way to the Mediterranean) from realising their presence until it was too late. Unfortunately for the French, two factors played against them. The first was that Bligh had already ordered some of his frigates to patrol the French coast as an early-warning system against just such an attempt, and one spotted the fleet within sight of the French coast. Here, the other factor came into play: British ships were, on the whole, faster than their French counterparts, and Bligh was able to receive the warning and send a superior squadron into position before the French could reach Ireland. On 25 June 1797, at the Battle of Crookhaven near Bantry Bay, Bligh met the French and smashed their fleet, a storm after the battle adding to the losses for the scattered and havenless French. The rebellion in Ireland never arose, as without French support such an attempt would be hopeless.

Not all went well for the British in the opening stages of the war, especially behind the front lines. Despite the presence of the Levellers in government and the relative liberalism of the British government for the time, revolutionary sentiment was not entirely gone in the Empire. Colonial uprisings, especially in the Cape colony, had little to no effect on the war itself, but one struck closer to home in May of 1797. With the Army of Flanders out of position, and news from the south mixed (the death of MacDonald meant that some believed that the British had in fact lost the battle), many in the French-speaking parts of the region began to call for reunification with France or the creation of a separate country allied with France. The result was a sudden and general uprising known as the "Peasants' War", which the French gleefully supported with everything they had. The Army of Flanders was ordered to continue its operations in France, but would recieve no reinforcement as that was diverted to form an army to deal with the rebellion. Back in Britain itself, however, the Patriots began to protest the war, noting the Walloon rebellion as an example of the violence that the Levellers were supposedly encouraging with their support of the Batavian Republic. The Patriots were unable to stop the war or push Fox out of the government, but they did introduce a sizeable amount of confusion and contention into Parliament at a time when Fox desperately did not need it.

For France, however, any help was quickly becoming too late. The rest of the Coalition was arriving in Alsace and Lorraine; the main army alone, composed of soldiers from the Palatinate, Baden, Austria, and the Netherlands, reached well over 100,000 men by the middle of 1798, the largest single army ever organised in Europe to that point. With any need to screen such a large force well in the past, the Army of Flanders, now under the command of Charles Cornwallis, could strike further inland. His first goal was Paris, which he took on 5 May 1798; it was at the old Capetian capital that the war took an odd turn. The presence of a British army so deep within French territory suddenly reignited the old revolutionary fervour amongst the French, and soon after the capture of Paris, a group of the leading intellectuals of the country, headed by Jean-Francois Rewbell, an ethnically French lawyer from Lorraine, and Paul de Barras, an ambitious Provencal noble. With the support of several important administrators of Paris, the two declared a French Republic and sent a message to the British asking for their support. Cornwallis, of course, could not make such a decision, and so the matter was referred to Parliament. The result was yet another loud debate, as the Patriots felt that the addition of another republic to Europe would only make their spread faster, and warned that Britain might be the next country struck by anti-monarchist revolution. Elisabeth unofficially implied her support for the French republicans, while Fox did so more openly and directly.

The Patriots were rapidly losing power, however, as many of the upper middle class were becoming tired of their anti-Batavian standpoint. After several of them stormed out of Parliament and resigned their seats in disgust, on 23 July 1798 Parliament passed a somewhat compromise measure, recommending in quite diplomatic language that King Louis XI of France allow for a representative assembly for his own people; at the same time, the Council of State sent orders to the British armies in France to leave any intellectual and popular assemblies be until a more concrete understanding of what the post-war situation would be could be gained. Louis absolutely refused the former, obsessed as he was with his own divine right to absolute rule over his subjects, leading to the assemblies mentioned in the latter becoming more numerous and powerful. Even well outside of Coalition-controlled territory, revolutionary societies and direct rebellion began to appear, resulting in the diversion of vital forces from the front lines. Cornwallis pressed his advantage; on 21 May, a smaller British army under Arthur Wellesley, fresh from defeating the Walloons at Waterloo outside Brussels early in the year, attacked Calais and captured it easily. Calais had been a symbol of French resistance against the British ever since its success in holding off the Duke of York's assaults during the War of the Spanish Succession, and its loss was a huge blow to French morale. Cornwallis himself continued onward from Paris, and by 16 Nov Blois itself was in his hands.

Jervis and Nelson, in the meantime, had mostly been frustratingly idle. Based in Naples, they kept a close eye on the French Mediterranean coast, but the French fleet there aboslutely refused to sail out of Toulon, knowing that any attempt to do so would result in their own destruction. Nelson, for his part, had found a way to pass the time; he made the acquaintance of the British ambassador there, William Hamilton. More infamously, he met Hamilton's wife, Emma Hamilton, at the same time, and the two, entirely with William's knowledge and perhaps even encouragement, entered into an affair which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Horatia. The fact that the affair was so open only added to its shocking nature; Jervis was bothered that Nelson was paying more attention to Emma than he was to the French, but with the Toulon fleet entirely static he felt that it was an acceptable matter. Eventually, however, the two recieved new orders, as well as a small transport fleet with a few thousand soldiers: they were to seize the island of Corsica, joining with a Papal army and Corsican rebels in pushing the French off the island.

Emma Hamilton, by George Romney (1785)

The rebellion was led, militarily at least, by a young, revolutionary-minded Corsican noble, Napoleone di Buonaparte, son of the late Corsican representative to King Louis. Buonaparte had joined the French military and been well-educated in its ways; however, with the Batavian rebellion, his revolutionary opinions surfaced, and he fell out with Louis' government. With the main figure of Corsican resistance against France, Pasquale Paoli, in exile in Britain, it was Buonaparte who began agitating for an overthrow of the French, but it was not until the middle of 1798 that he finally had an opportunity. Noting the possibility of British aid, he sent a message to Paoli asking what might be needed to gain such assistance. Paoli relayed the message to Parliament and Elisabeth, along with the offer to make the latter Queen of Corsica in exchange for official guarantees of certain important rights. Parliament quickly agreed, and Paoli, along with what soldiers could be spared, was sent to the Mediterranean to meet with Jervis. Nelson, as soon as he was informed, quickly returned to military form, leaving the concerned and then-pregnant Emma Hamilton behind as he boarded Jervis' flagship, the 110-gun HMS

Victory.

Jervis had a special role in mind for Nelson. Although Nelson had made his fame fighting the French and Dutch at sea, Jervis knew that the young man had a true genius for coordinating naval and land actions, as he had shown in putting down the Caribbean rebellions in the 1780s. Nelson, therefore, would recommend to Jervis precisely how best to support Buonaparte and Paoli's land armies by sea. Nelson noted several potential landing points, emphasised the importance of capturing the major fortresses at Bastia and Calvi, and screening the invasion against the almost inevitable desperate attack by the fleet in Toulon. Most of this was simple common sense, but Nelson also insisted that Jervis keep in close contact with Buonaparte and Paoli and listen to their requests rather than attempting to use his rank against them, as proper coordination between the two would lead to either the success or failure of the campaign.*** Calvi was decided to be the first target, and British and Papal soldiers, along with Paoli, landed there in November of 1798, quickly overruning the fortress. Buonaparte and Paoli were given command of the army, capturing Corte in mid-December and moving to Bastia as Jervis' fleet screened the coast.

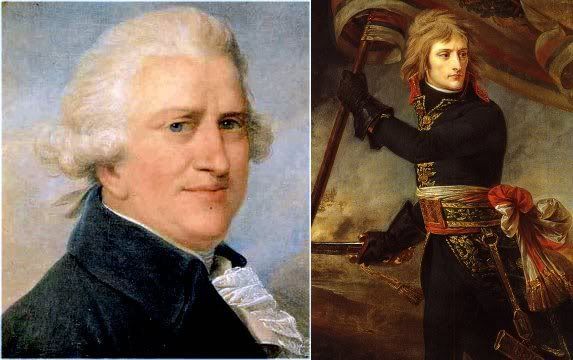

Pasquale Paoli, by Richard Cosway (date unknown) and Napoleone di Buonaparte, by Antoine Gros (1801)

On 3 January 1799, both fleet and army reached the large garrison at the same time. The Toulon fleet was nowhere to be seen - it never set out, even with this imminent threat - and so both forces could direct their attention at the fortress. Nelson pressed for an immediate attack, as did Buonaparte; Jervis and Paoli were more cautious, but agreed to the attack the next day once the others made their case. Once the two forces attacked, the result was barely in doubt; Jervis and Nelson easly took the seaside forts out of commission with their cannon, while the tactically brilliant Buonaparte overran the landward garrisons with apparent effortlessness. The fighting, however, cost Nelson his life; at one point, a sniper in one of the fortifications pierced his lung and broke his back, mortally wounding him. Still, Corsica was safely and solidly in British hands, Paoli being appointed President of the Corsican assembly and Buonaparte the commander of the Corsican military. Nelson's body was preserved, returned to Britain, and buried, after a state funeral, at Saint Paul's, in a coffin made from wood salvaged from the

Orient.

The Apotheosis of Nelson, by Scott Legrand (1810s); in an error, the painter showed Nelson as having lost his left arm, rather than right.

The war was, of course, not yet finished, as a large French army under the Marquis de la Fayette marched north to try and retake Blois and Paris. By this point, the Batavian Republic was in no danger, and Alsace and Lorraine likely to return to Palatine control (as well as Calais and Corsica likely to become British), but the Coalition was tired of constant trouble from the French monarchy, and intended to put France to rest once and for all. This goal could not be achieved until the French military was entirely destroyed, and the Blois-Navarre monarchy could be replaced throught the entire country with whatever post-war regime the Coalition agreed to. On 5 May 1799, la Fayette's army, having pushed north of the Loire river in an attempt to cut Blois off from supply lines from Bretagne and the Channel, was met at Vermeil in Maine by the British under Wellesley, and the latter swept the former aside with surprising ease. Wellesley was able to use the folds of the land to his advantage, surprising the French attack with a withering volley at close range from a previously-hidden line of soldiers. This was followed by the arrival of a German cavalry force, combined from all the states of the Empire, under Gebhard von Bluecher, who swept the field clean of French soldiers.

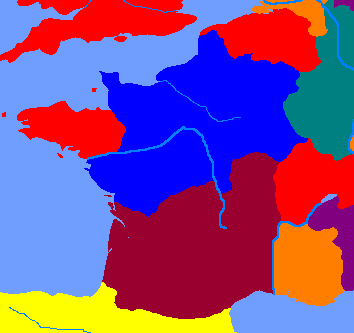

France now lay defenceless, and the Coalition continued southward. General revolt in southern France removed Louis' last stronghold, and the king himself was captured by revolutionaries in late June, sent north under heavy guard to stand trial in Blois. The revolutionary government itself signed several agreements: Corsica and Calais were surrendered to Britain on 10 July, Alsace and Lorraine to the Palatinate on 17 November, and portions of the Free County of Burgundy to Helvetia on the same day. After two years of bloody and wide-ranging war, and a decade and a half of revolution throughout western Europe, the situation in that region had been changed permanently and shockingly. Two new republics now stood where monarchies had been, and the various nations of Europe met in Vienna to put forth a permanent agreement on how the whole continent would look going into the 19th century.

_________

*Nelson had only frigates and third-rate 74-gun ships, including his flagship the HMS

Vanguard and the decidedly poorly-named HMS

Goliath.

**The fact that the town had the same name as the site of d'Audley's infamous 1397 defeat was not lost on the well-educated MacDonald.