Turko-Egyptian War, Part I

Secular War, Holy Peace: A History of Relations between Mid-East States in the 19th Century - Professor Nafi Ahmed al-Raschid Cortez y Freeman, 1999, Royal University of Amman Press

The Turko-Egyptian War began as an anomaly; a quirk in the chain of events, resulting from an over eager Emperor, and a cautious Prime Minister. The situation, had it played out properly, would more likely have resulted in a Jeruso-Egyptian War.

The Situation began when Muhammad Ali, Sultan of Egypt, expelled all the Levantine Catholics from Egypt in February of 1835; Ali intended to claim the title of Caliph, and wanted to present an image of a “Pure Egypt” to the Muslim world. The Patriarch and Napoleon II were outraged, and the King ordered the Royal Army of Egypt mobilized in preparation for crossing the Suez.

Mahmud II, carefully forgetting the Battle of the Old City, decided this would be a great opportunity to remove the Jerusalem, once and for all. In retrospect, such an assumption is comical; however, one must remember that the Ottomans had spent the last century reforming and refining their entire government and society, along more European lines, where as Jerusalem appeared to be falling apart, loosing Egypt west of the Suez in 1730, the Regency falling to the Habsburgs in 1793, and finally the Napoleonic Wars, where Foreign Army’s made it to the city gates, and nearly entered the city for the first time since Saladin. Most Observers believed that Jerusalem would be thoroughly thrashed, though the Great Powers would not have allowed for its dissolution.

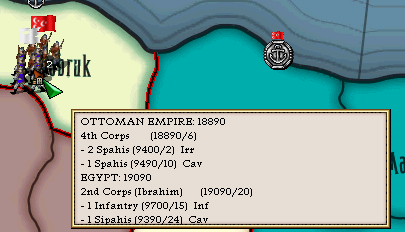

The Ottoman Emperor, in his mind abiding by the terms of the Turko-Egyptian Alliance, landed troops in Alexandria in April, intending to march them to bolster the fortress at Zigzag. However, the forts Egyptian defenders, acting under express orders from the Egyptian Sultan, promptly fired upon the arriving Ottoman soldiers; Ali felt he had to fight this war alone, as to enhance his prestige.

Now it was the Emperor’s turn to be furious, and, in what virtually all historians agree to be a “rash and hasty” decision, declared war on the Sultanate of Egypt. It was then that Ali, in a move that surprised all his contemporaries, committed the cardinal sin of Political Islam: he asked the Crusaders for help.

The situation in Jerusalem was an interesting one. A week after the Royal Army of Egypt had been mobilized, King Napoleon II had fallen off his horse in a hunting trip, dieing upon impact. As per the law, the kingdom passed to his infant son; however, the king had failed to name a regent in case of his son coming to the throne before his majority. Thus, the task of naming a regent fell upon the House of Nobles, the upper house of the Jerusalem Parliament, which was in turn dominated by the Prime Minister Raphael von Wittlesbach Delgado de Lusignan-Alexandrov, Prince of Beirut.

PM Alexandrov was a notoriously cautious figure to his contemporaries, though remembered more for his revanchist rhetoric and policies. After the King’s death on March 2nd, 1835, Alexandrov proposed an extremely controversial figure as Regent for the young Carlos I: the Queen-Mother Isabella, who was well known in Jerusalem circles as a “wonderful and charming lady who probably could not spell 'Jerusalem' if she had to.” The Prime Minister intended her to simply tie up the procedure, and allow him a free hand to stave off what he saw to be a potentially disastrous war.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities between the two Muslim powers, Alexandrov intended to broker a settlement with the Sultan, while hoping to extract concessions from the Ottoman Emperor; the Prime Minister understood that Jerusalem could not afford a two front war, especially against their formidable Ottoman Nemesis. Even when the turn of events brought the Egyptian ambassador to Parliament at Temple Mount, the Prince of Beirut hesitated before heeding the calls for alliance. When asked why he was helping the Sultan, the Prime Minister is said to have replied “Jerusalem cannot afford a war with the Emperor in Syria and the Jordan. Jerusalem cannot win a war with the Emperor in Syria, the Jordan, and Egypt.”

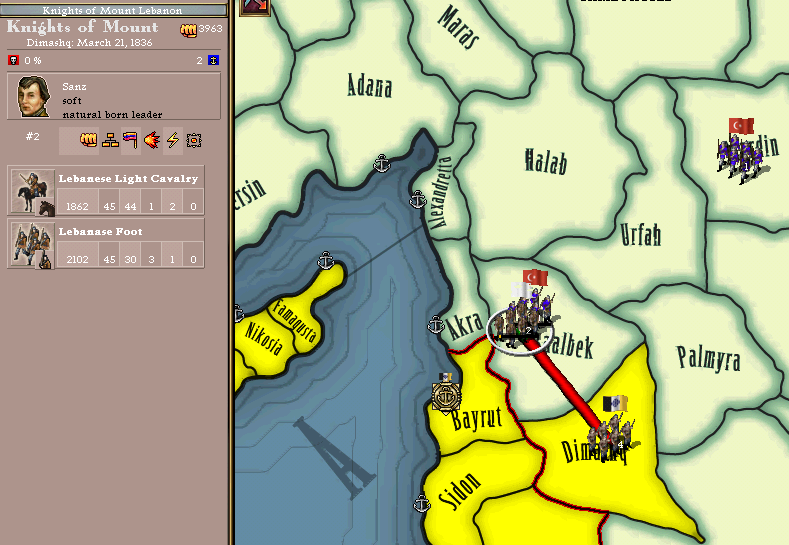

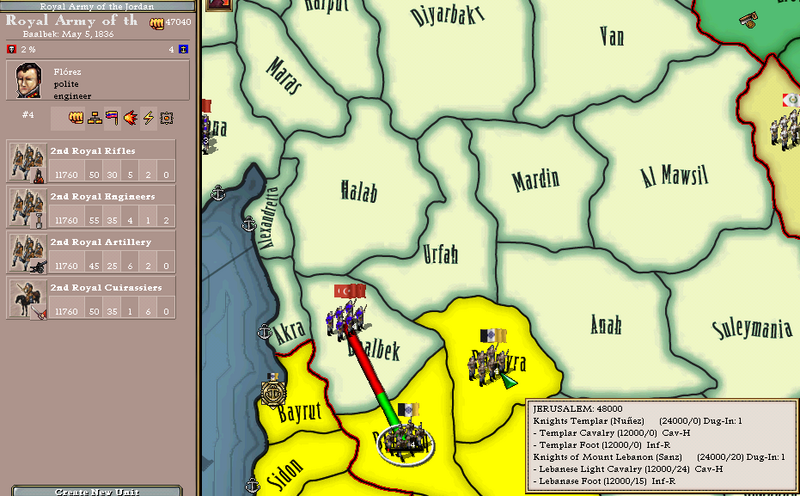

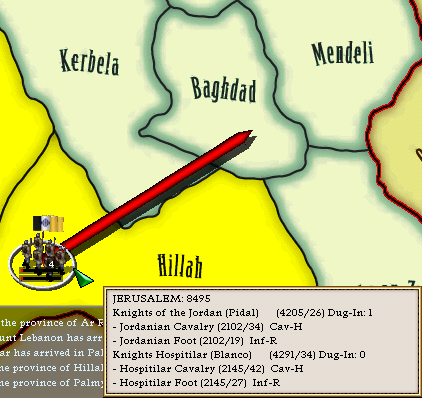

When hostilities finally commenced, the Army of the Jordan moved to capture Damascus, while the Knights Hospitaller, Templar, and of the Jordan, moved over to Ottoman Jordan. The Knights of Mount Lebanon engaged a force of some 10,000 Infantry in Baalbek. Though the Prime Minister had hoped these forces would be enough, he understood that this conflict would soon spiral beyond a limited war, and determine Jerusalem’s course for the 19th century.

Secular War, Holy Peace: A History of Relations between Mid-East States in the 19th Century - Professor Nafi Ahmed al-Raschid Cortez y Freeman, 1999, Royal University of Amman Press

The Turko-Egyptian War began as an anomaly; a quirk in the chain of events, resulting from an over eager Emperor, and a cautious Prime Minister. The situation, had it played out properly, would more likely have resulted in a Jeruso-Egyptian War.

The Situation began when Muhammad Ali, Sultan of Egypt, expelled all the Levantine Catholics from Egypt in February of 1835; Ali intended to claim the title of Caliph, and wanted to present an image of a “Pure Egypt” to the Muslim world. The Patriarch and Napoleon II were outraged, and the King ordered the Royal Army of Egypt mobilized in preparation for crossing the Suez.

Mahmud II, carefully forgetting the Battle of the Old City, decided this would be a great opportunity to remove the Jerusalem, once and for all. In retrospect, such an assumption is comical; however, one must remember that the Ottomans had spent the last century reforming and refining their entire government and society, along more European lines, where as Jerusalem appeared to be falling apart, loosing Egypt west of the Suez in 1730, the Regency falling to the Habsburgs in 1793, and finally the Napoleonic Wars, where Foreign Army’s made it to the city gates, and nearly entered the city for the first time since Saladin. Most Observers believed that Jerusalem would be thoroughly thrashed, though the Great Powers would not have allowed for its dissolution.

The Ottoman Emperor, in his mind abiding by the terms of the Turko-Egyptian Alliance, landed troops in Alexandria in April, intending to march them to bolster the fortress at Zigzag. However, the forts Egyptian defenders, acting under express orders from the Egyptian Sultan, promptly fired upon the arriving Ottoman soldiers; Ali felt he had to fight this war alone, as to enhance his prestige.

Now it was the Emperor’s turn to be furious, and, in what virtually all historians agree to be a “rash and hasty” decision, declared war on the Sultanate of Egypt. It was then that Ali, in a move that surprised all his contemporaries, committed the cardinal sin of Political Islam: he asked the Crusaders for help.

The situation in Jerusalem was an interesting one. A week after the Royal Army of Egypt had been mobilized, King Napoleon II had fallen off his horse in a hunting trip, dieing upon impact. As per the law, the kingdom passed to his infant son; however, the king had failed to name a regent in case of his son coming to the throne before his majority. Thus, the task of naming a regent fell upon the House of Nobles, the upper house of the Jerusalem Parliament, which was in turn dominated by the Prime Minister Raphael von Wittlesbach Delgado de Lusignan-Alexandrov, Prince of Beirut.

PM Alexandrov was a notoriously cautious figure to his contemporaries, though remembered more for his revanchist rhetoric and policies. After the King’s death on March 2nd, 1835, Alexandrov proposed an extremely controversial figure as Regent for the young Carlos I: the Queen-Mother Isabella, who was well known in Jerusalem circles as a “wonderful and charming lady who probably could not spell 'Jerusalem' if she had to.” The Prime Minister intended her to simply tie up the procedure, and allow him a free hand to stave off what he saw to be a potentially disastrous war.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities between the two Muslim powers, Alexandrov intended to broker a settlement with the Sultan, while hoping to extract concessions from the Ottoman Emperor; the Prime Minister understood that Jerusalem could not afford a two front war, especially against their formidable Ottoman Nemesis. Even when the turn of events brought the Egyptian ambassador to Parliament at Temple Mount, the Prince of Beirut hesitated before heeding the calls for alliance. When asked why he was helping the Sultan, the Prime Minister is said to have replied “Jerusalem cannot afford a war with the Emperor in Syria and the Jordan. Jerusalem cannot win a war with the Emperor in Syria, the Jordan, and Egypt.”

When hostilities finally commenced, the Army of the Jordan moved to capture Damascus, while the Knights Hospitaller, Templar, and of the Jordan, moved over to Ottoman Jordan. The Knights of Mount Lebanon engaged a force of some 10,000 Infantry in Baalbek. Though the Prime Minister had hoped these forces would be enough, he understood that this conflict would soon spiral beyond a limited war, and determine Jerusalem’s course for the 19th century.

Last edited: