Bold, and perhaps foolish, to abandon the one sure ally in a sea of enemies.

- 2

A crucial early test passed.By 963 the last of the invaders had been ejected from Persia, the Ziyarid state had survived its gravest test.

It must be done, but will no doubt be costly.By the end of the 970s, having held the invaders at bay for two decades, elites within Persia once again started to turn their attention towards expansion.

Perhaps this was the only practical route in the short term, but it seems both a bit underhanded of Vushmgir and possibly counter-productive strategically: discarding and attacking a hitherto firm ally against the Muslims instead of trying to carve a slice off one of their old enemies. It will be interesting to see if this bold but nefarious move pays off in the long run.with the Armenian-Persian alliance having held strongly for a generation, the Christian Kingdom’s defences were clearly stronger on its other frontiers. Eyeing a quick and easy victory, Vushmgir II would betray his grandfather’s pact of friendship with the mountain kingdom and invade Armenia in 980. It was a decision that would have great consequences for region for a generation.

Oooh. Just noticed this one. Absolutely onboard for some Zoroastrian restoration antics!

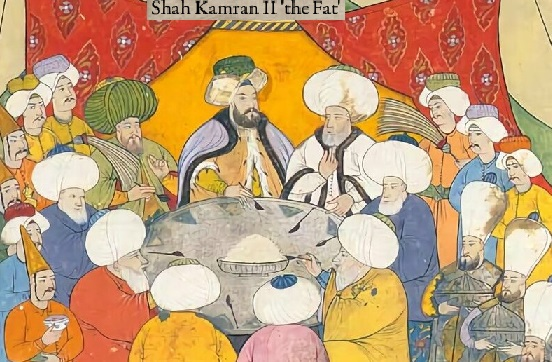

Also, I was amused to see this...

This is one of the images that I used in the header image of my AAR. Obviously, in a less serious manner than you. I think I googled "Armenia" and "Medieval" and thought "Oooh. I could write a funny caption for that!"

Leave those poor Aremenians alone! #sueniktisforthee

Hopefully, those expansionist elites don't overextend. Or they don't turn on each other and the regime...

The Ziyarids have weathered the first great storm. Hopefully their Armenian adventure won't end as disastrously as those of their Iranian forebears.

Bold, and perhaps foolish, to abandon the one sure ally in a sea of enemies.

A crucial early test passed.

It must be done, but will no doubt be costly.

Perhaps this was the only practical route in the short term, but it seems both a bit underhanded of Vushmgir and possibly counter-productive strategically: discarding and attacking a hitherto firm ally against the Muslims instead of trying to carve a slice off one of their old enemies. It will be interesting to see if this bold but nefarious move pays off in the long run.

Ah, Zoroastrianism. One of my favourite religions to play and not just because of the meme potential of divine marriages.

A couple of very good chapters. I like the more historical side of things and I have a very big bias to reviving dead/fading religions per my own workI will be sure to keep up with this one!

In #9, I saw an independent Albania. To the Adriatic, they will march! Thank you for this work.

Hey Tommy! Dropping in to say hello and joining along with whatever sparse time I still have and give to these forums!

A somewhat ill-starred reign the Ziyarid state was lucky to survive. That Armenian ploy certainly backfired badly.Having struggled for authority throughout his reign, Vushmgir was a deeply unpopular ruler, maintaining his grip on power by ceding authority from the crown to the nobility. Few mourned his passing in 1014

Ooh, a post-succession fratricidal conflict: juicy!For the next three years court in Isfahan was dominated by factionalism and bickering between Ebrahimites and Kamranites

At least it was a coup and murder rather than another messy and drawn out civil war. We shall see if Kamran can achieve stability from the chaos. Though fear, murder and treachery are not necessarily ideal things to base a revival on.After an era of Ziyarid history in which the realm had been ruled over by a Shah remembered for his treachery, another with a known fratricidal kinslayer was about to begin.

Persia - where backstabbing is elevated to a national pastime. Thank you for the update.

Well, from the burning ashes to the raging fire, the next reign will surely be another hard test.

A somewhat ill-starred reign the Ziyarid state was lucky to survive. That Armenian ploy certainly backfired badly.

Ooh, a post-succession fratricidal conflict: juicy!

At least it was a coup and murder rather than another messy and drawn out civil war. We shall see if Kamran can achieve stability from the chaos. Though fear, murder and treachery are not necessarily ideal things to base a revival on.Interested to see whether his methods will veer towards conciliation or the iron fist. Or perhaps even a bit of both.

Ah Armenia, where Persian kings and their dynasties go to die. Vushmgir might have gotten out of there with his life, but it seems he still fell under the curse nonetheless. If Zoroastrianism has an equivalent concept for the Greeks' hubris, then it certainly appears that he has fallen afoul of it.

And I can't be the only one who finds the "crushed by a pillar" story to be just a little too convenient...

Damn that Vushmgir backstabbing his biggest ally. That Persian-Armenian bromance was one for the ages, but cut short by a monarch's poor decisions. I wonder if any supporters of Ebrahim remain loyal to him even after his death? Did he leave any children behind? If he did, I doubt they'll be long for this world with their murderous uncle so close by.

Surviving simultaneous Jihads is a great feat. Marrying your young niece is smooth diplomacy. The Crusades for the next century and a half will be an ally as the Islamists are a bigger immediate threat than the Catholics. After unifying Persia, expansion can go in any direction. Thank you for the update.

Kamran has managed to leave Persia in a much better state than he found it. With the Islamic powers licking their wounds, perhaps now would be a good time to start reasserting the empire's traditional borders.

It's a bit upsetting that his kinslaying tarnished what would otherwise have been a spotless and lustrous reign. He could have earned the epithet of "the Great" even, as his leadership of Persia truly merited it, but alas, he could not have become king in the first place had Ebrahim not fallen.

With the Sunni and Shia coalitions defeated, and both branches of the family (hopefully) fully united after the marriage of the King and his niece, it seems Persia might be in for a period of conquest it seems. Few will be able to oppose the next king, at least from the outset.

A remarkable reign indeed! Hopefully the future remains bright.